THE GROUP EXHIBITION “THE HOUSES WE NEED”

Participants: Anna-Liisa Unt, Arhitektuurikool, b210, Elina Liiva ja Helena Rummo, Johanna Jõekalda ja Artur Staškevitš, Kadarik Tüür Arhitektid, KUIDAS, Leonhard Lapin, LLRRLLRR, Margit Mutso ja Inke-Brett Eek, Molumba, PART, PLUSS, Peeter Pere, Raoul Kurvitz, Stuudio Tallinn

Curator: Jarmo Kauge

Spatial design: Eva Kedelauk and Kristel Niisuke

Graphic design: Margus Tamm

11.06-21.11.2021 at Estonian Museum of Architecture

The group exhibition, The Houses We Need at Estonian Museum of Architecture (11.06-21.11.2021) showcases 16 commissioned designs for houses ‘with the aim of ensuring a more beautiful, secure and peaceful future on planet Earth’.

As much as I want to start skipping the pandemic as a talking point at the beginning of every article, crossing the gulf from Helsinki to Tallinn has probably never felt more like big-time travelling than it currently does. Also, I probably was not the only vaccinated EU citizen who was looking forward to a museum visit on a fine summer weekend. On that note, The Houses We Need, the 30th anniversary exhibition of the Arhitektuurimuuseum puts on a fresh-faced show, at least, for those of us still trying to foster some forms of utopianism in the evermore troubling global future.

But first, let’s rewind that future back a few decades. While still onboard the ferry watching Tallinn’s skyline slowly coming into focus, I could not help thinking how I have been travelling this way to Estonia ever since the early 1990s. And perhaps from the rather static perspective of Finnish architectural solemnity, contemporary Estonian architecture and urbanism has felt more reactive to current signals or tendencies, and willing to go through multiple speedy cycles. I remember the first glazed bank towers when they appeared in the Tallinn skyline, all the novel buildings that experimented with materials, colours and motifs as an exploration of newness. Then came the gradual (and on-going) gentrification of the old town, the neo-monumentalism of Kumu and the architectural reclaiming of the Freedom Square and other symbolic spots. Recently, art spaces, reappropriated industrial areas, heritage and urban edges have emerged. A lot of technological innovations, urban systems, exhibitions and new plans have been presented. But if this all has been a fast-forward development, then where are things currently?

The more jaded view is that all things are becoming commercially and visually similar everywhere. That by now, we all live in an era where architecture or design is mostly mediated through screens, validated by Pinterest and our modes of criticality moulded by buzzwords on e-flux. So perhaps that is why it is quite refreshing to see an exhibition that talks about a need for houses, regardless of how they are defined. In this case, it is my interpretation that we are looking at houses as vehicles or vessels for architectural thinking, but in a way that is very much rooted in the media-centred and mediated contemporary experience.

The group exhibition, The Houses We Need, showcases 16 commissioned designs for houses ‘with the aim of ensuring a more beautiful, secure and peaceful future on planet Earth’. At face value, the phrasing may seem slightly naïve, but in today’s world, I somehow like its earnest tone. In conversing with museum director Triin Ojari, I find it inspiring to learn that the project originated from a round-table discussion with the museum staff, with them deciding to go ahead with photo archivist Jarmo Kauge’s idea towards an exhibition. As Kauge’s curatorial brief then called the contributors to come up with ‘speculative solutions, raise questions and show alternatives’, one may read it as a clear invitation to the visionary side of design practices. But for me, what stands out in the call is the institutional permission for a certain blue-eyedness and sense of irony. In today’s curatorial world filled with urgency talk, it is indeed a welcome release. But let’s finally step into the show.

The resident Estonian architectural visionary Leonhard Lapin’s concrete architecton 30 greets visitors at the entrance. As part of the exhibition, from the get-go I sense it represents the greatest amount of permanence displayed in the show. The sculpture-like form will remain in place even after the exhibition, at least for some years according to Ojari. Lapin’s work is a comment on the potential of modern architecture, in comparison to contemporary property development’s focus on making every square meter profitable.

The rest of the show operates very much in the context of today’s information-ridden environment, although the 15 remaining projects are displayed together in a visually coherent space indoors. There is enough polish in the exhibition design and graphics for the showing to feel special for the occasion. The items and panels have been put on display following a strong ‘Miesian’ grid space that quite readily grants a license to talk conceptually about the future and other abstract things. The calm presentation works especially well with mostly pictorial presentations, such as Laura Linsi and Roland Reemaa’s poetic panel painting Allegory of a Water Treatment Plant as well as the delightfully Buckminster Fuller-esque Captain Nemo House by artist Raoul Kurvitz.

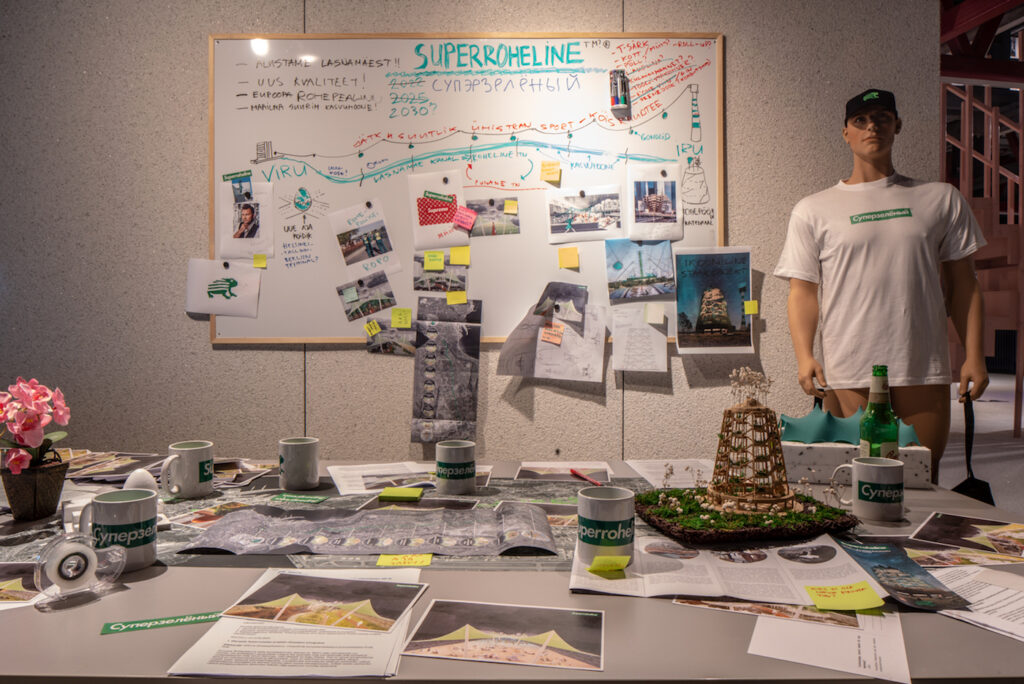

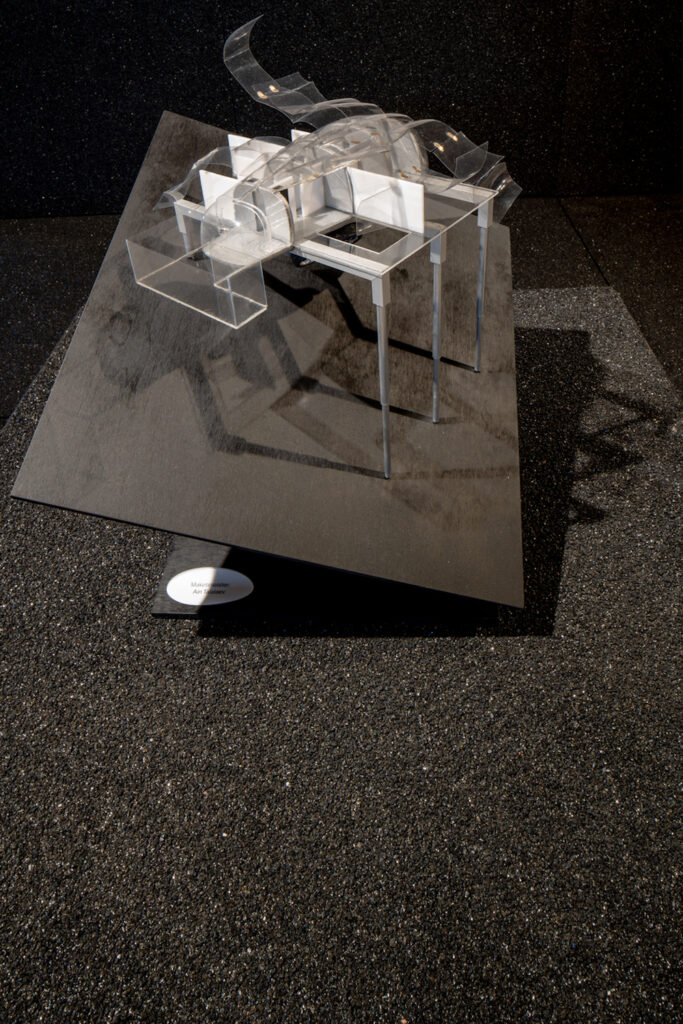

There is also a good amount of humour. The branding workshop-like display Supergreen by young Estonian office Molumba is not too far-fetched from some actual brainstorming sessions I can vaguely remember having participated in. In Hotel paradox by Helena Rummo and Elina Liiva, scale models of futuristic hotel living play with spatial absurdity as a commentary on the future of the wastefully abundant Western lifestyles. Even Soviet-era housing realness is shown to have its quirks, displayed in the project New Forms of Equality by Johanna Jõekalda and Artur Staškevitš. The work plays with the possibilities of more human-centric worlds amidst and in between the rough mass-produced housing blocks, looking into a future where the ideological messages of existing structures ultimately start to lose their imprint.

Another angle that the exhibition puts on display, though more implicitly, is the ecological and post-humanist viewpoint. Starting from ecologist Tuuli Sepp’s essay in the exhibition catalogue, the underlying sentiment is that perhaps we as species should not remain so overtly confident with our current understanding of living or building practices. Could we live without the comfort of contemporary buildings? I find some correlation with this line of thinking in the work How do we need a house? by group Kuidas (How), which in a very minimal way shows layers of clay that are cast on site, creating a model of a possible habitat or a novel architectural system—just in case we might need it, whenever we may run out of concrete, or so. Another solution-cum-question presented for the darker times ahead is the proposal Limestone by architect Peeter Pere, presented with a diorama-like display of a limestone quarry in gripping detail.

While browsing through the projects, I wonder how the audience, media or the Estonian society have received the exhibition so far? What are the things people notice in comparison to ideas that might potentially turn them into co-utopians? Triin Ojari notes that so far, the media has chosen to use images of certain exhibited projects based on the fact they seem to have more distributable imagery, such as the renderings of the Waste Temple by Kadarik Tüür Architects. While visually appealing and detailed, the temple is one of the most chilling views of the future, blending in religion, status, wealth and waste into an impactful dystopian social mixture. Another photogenic and perhaps a more hopeful visual is offered by the project Sartorial Space by b210 architects. In their proposal made of Estonian wool, both the post-apocalypse nomads and the utilitarian minimalists can find refuge in a portable, wearable and habitable woollen garment.

Nevertheless, I do feel I ultimately exit the exhibition with a far more hopeful sentiment rather than it just adding to the already existing angst about the future that so many of us share. The best parts of the exhibition I think try to reach beyond scenarios where the world as we know it will in some ways end, fade away or change. They show that architecture or vision-building does not automatically end at the end of the world. While this is arguably an architecture-centric view, it still is an important conceptual addition to the mainstream conversation about sustainability and green buildings. Obviously, all our focus on sustainable technologies and solutions is commendable, but we must acknowledge that much of the sustainability talk still somewhat assumes that the overall societal or economic development narrative will remain the same. The hopeful message is that architecture has its freedom and design can be intellectually and artistically possible regardless of the circumstances and future scenarios.

On my way back aboard the last ferry of the day, I cannot escape the feeling that the exhibition somehow also stems from the contemporary experience of a small country in a world where challenges are global. At least to my eyes, Estonians are never oblivious to understanding power, or let’s say, forces that make the world go round. In today’s world, this means big tech, social media, visibility, or social commentary—and the vast looming disasters ahead. (As a side note, the archival photo collages on display of the smaller exhibit on the mezzanine floor above the main hall focusing on the displays of power in architectural design and imagery do not feel at all out of place in this regard.) Thus, as an afterthought, I want to re-read the title of the exhibition as a wider manifesto. Written in between the lines of The Houses We Need, one can see embedded a call for fellow utopians in general. If architects and designers do not otherwise have the agency, it can be the role and opportunity of a museum in creating the space for discussing our shared, potentially difficult, and inevitable future.

MIKA SAVELA is an architect and curator based in Helsinki. He previously served as the editor-in-chief of Finnish Architectural Review and currently works as an advisor in architectural policy.

HEADER: ‘New Forms of Equality’. Johanna Jõekalda and Artur Staškevitš

PHOTOS by Evert Palmets

PUBLISHED: Maja 106 (autumn 2021) with main topic Spatial Revolutions