Contradictions of spatial planning are caused by the time required to process comprehensive and detailed plans as well as (spatial) gap between the two. How to better make sense of planning processes and to alleviate rigidity of the aforementioned?

Urban planning—drawing up the plans, to be precise—is an ambivalent issue in our judicial area. It is the responsibility of the local government to organise the formulation of three types of planning. Setting aside the special plans of the local government as a highly specific and rare type of planning, the local government jurisdiction mainly includes comprehensive and detail plans, while the comprehensive plans may, in turn, be specified with sectoral thematic plans. If the aim of the comprehensive plan is to lay down the principles and trends for the spatial development in the local government for the next 10–20 years, then the detail plans are drawn up to implement the comprehensive plan and create an integrated spatial solution for the construction activities in the coming years.

In addition to improving the living environment, the underlying principles of planning include public participation and information as well as balancing and integrating interests. Participating in the planning process does not require individual concern—everybody can stand up for public interests.

All the above have also formed the ground for the first major controversy in the area: the time for drawing up the plans is approximately the same as the expected time of their implementation. As a result, we may be faced with a time delay where the new plan may no longer be relevant at the time of its adoption.

The second controversy is based on the fact that in practice local governments delegate the drawing up of detail plans to private entities interested in the construction. It is generally believed that once the planning process is launched by a clearly formulated private interest, it also requires stricter control by the local government. Thus, we end up with unnecessarily detailed planning solutions that come inappropriately close to the realm of building design projects. Due to the excessive interest and the relatively short political government cycle, comprehensive plans tend to remain highly general and we thus come to the core of the problem—the immense (spatial) gap between the level of detail of comprehensive and detail plans.

How to ensure better relevance of plans and bridge this gap? There have been discussions about the so-called living, permanently up-to-date comprehensive plans for more than 15 years. That was when we at the Tallinn City Planning Department (the predecessor of the Spatial Design and planning department) began to draw up so-called structure plans for the more complex areas in terms of urban design—spatial design document that in terms of the size of the particular site and the degree of precision was positioned appropriately between the two plan types.

The urban design arguments provided by the structure plan are indeed set at the price of some legal arguments, however, the compromise is more than fair as far as the achievement of a better living environment and high-quality spatial design are concerned.

The structure plan reflected primarily the urban design vision of the local government: to provide a flexible and up-to-date spatial interpretation of the valid comprehensive plan and set the starting position for drawing up the detail plans thus anticipating the vision of the person interested in the plan. The structure plan focuses on the spatial aspects of the quality and identity of the area rather than on the traditional numeric values of plans.

Both the pros and cons of the concept used to this day lie in the fact that according to the Planning Act it is not a plan. As it is being drawn up, no strict procedural processes are followed, the local government bodies will not enforce it and it will not be a legally binding document. At the same time, its formulation is based on all the fundamental principles of planning stated by law, including the principle of participation and balancing interests. The urban design arguments provided by the structure plan are indeed set at the price of some legal arguments, however, the compromise is more than fair as far as the achievement of a better living environment and high-quality spatial design are concerned.

Nevertheless, the strive for spatial design based on the general spatial awareness and spatial culture could free the planning process from the strictly formalised procedures and, similarly, the discussions on spatial decisions from legal arguments and instead search for solutions in consensus and co-creation. The concept of a structure plan is a small step towards it.

Despite its size, the area of Mustjõe structure plan is rather demanding in terms of urban design: in the south, it is bordered with the noisy Paldiski Road that is suitable for taller highrises but not for residential buildings. In the north, however, there is Kopli Bay with its environmentally vulnerable coastal reed, non-motorised traffic path and the restricted area of Kopli range lights. The given structure plan was motivated by the pressure for development by the landowners on the undeveloped land. At the moment, several buildings have been completed pursuant to the structure plan.

Sikupilli structure plan was drawn up for the area next to Pae Park. The proximity of the popular recreational area activated the owners of abandoned industrial areas who wished to construct tall buildings. At the same time, the industrial areas adjoin a clearly structured and comprehensively improved urban district with heritage features. The structure plan aimed at redefining the industrial areas based on the current urban design qualities without damaging the given areas. Unfortunately, its implementation is stuck in legal disputes.

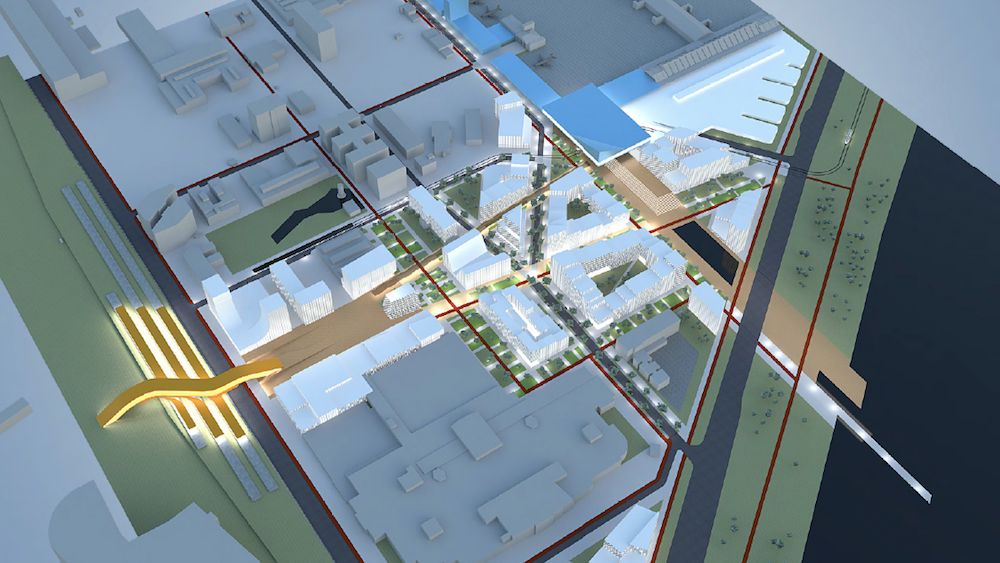

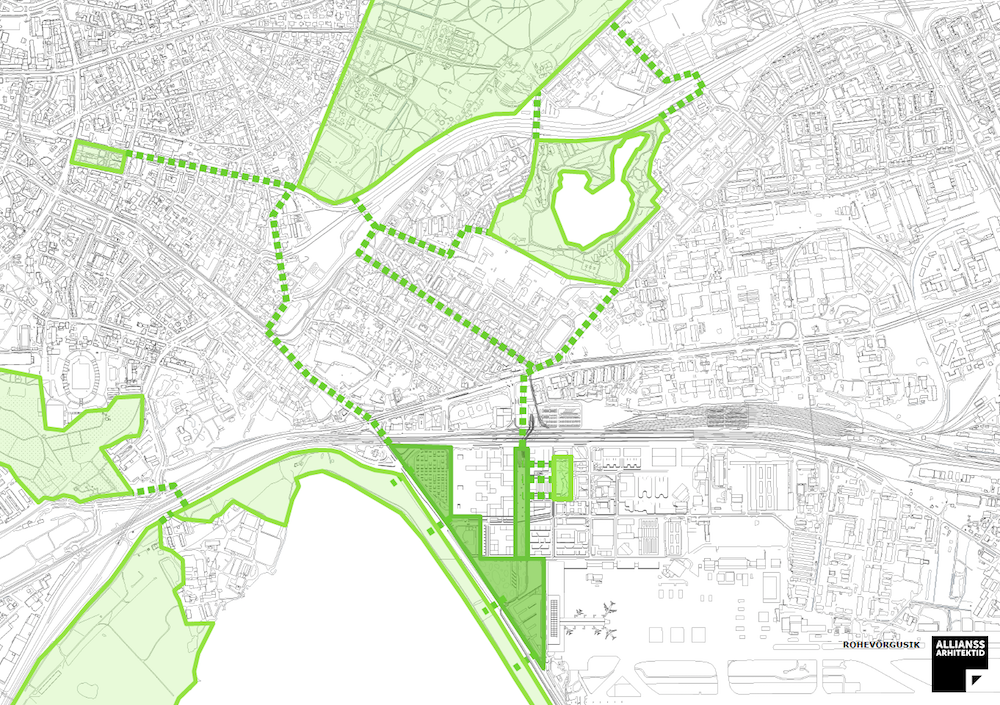

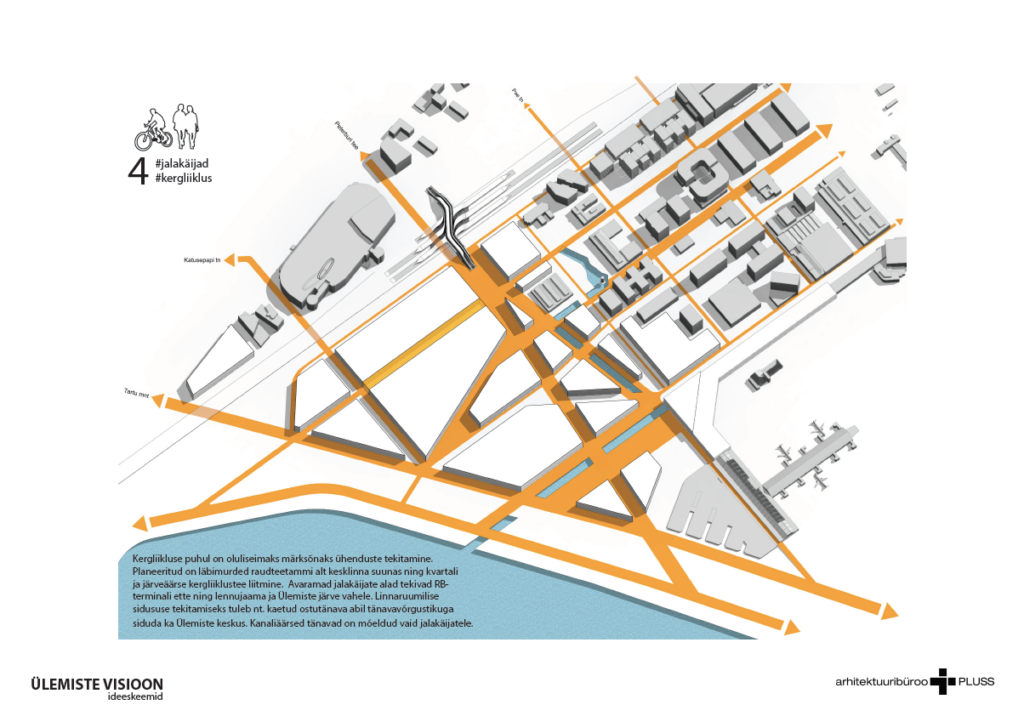

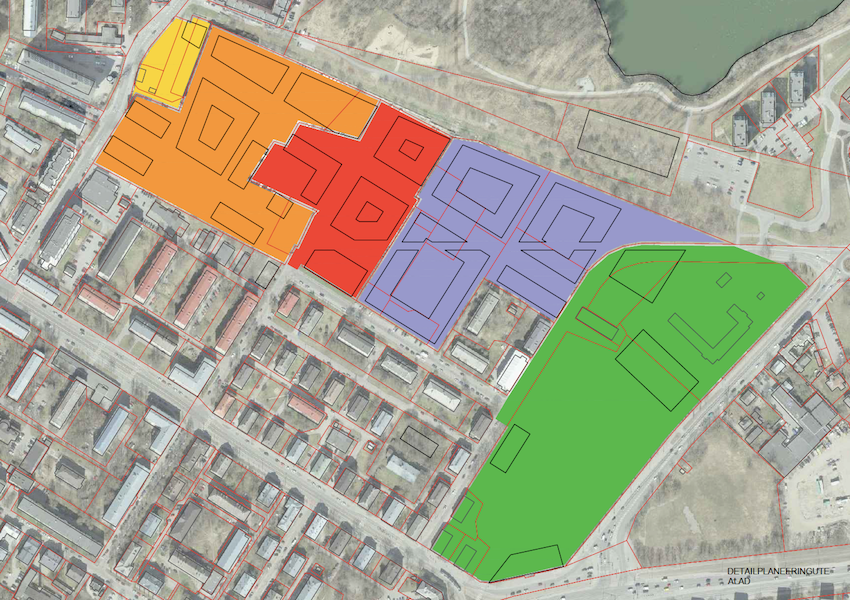

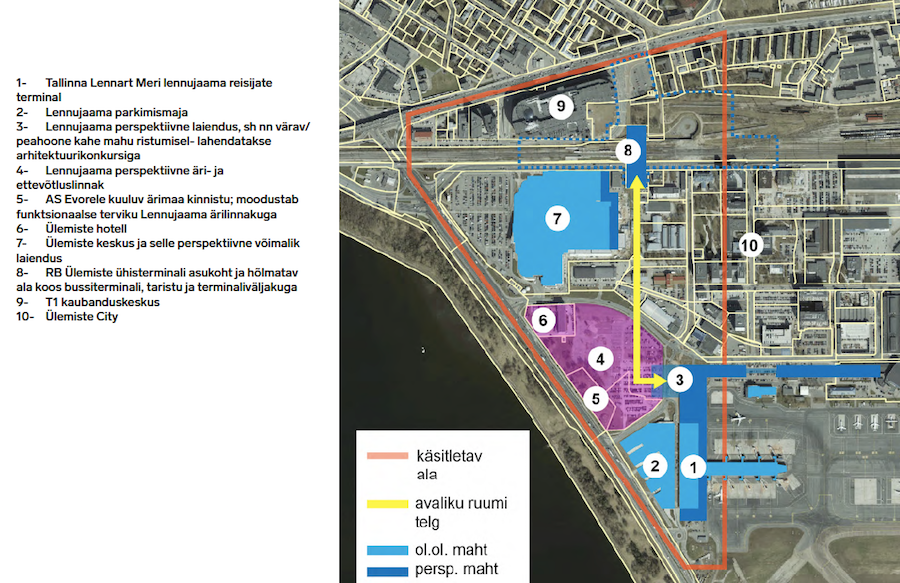

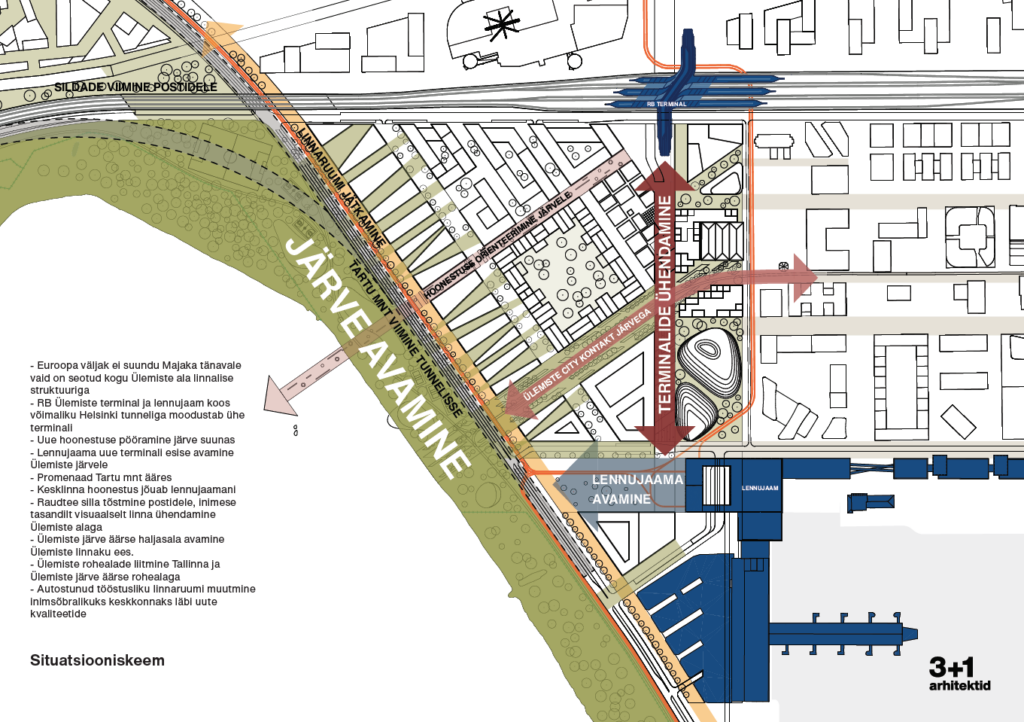

For the structure plan near the airport and Ülemiste City, we conducted several studies and cooperated extensively with the developers in the area, including Tallinn Airport. In addition to the urban planners of the Spatial Design Centre of Excellence, we also included specialists of well-known architecture offices in our search for a functioning and diverse spatial structure of the Estonian air gateway. The parties agreed on the urban design vision, however, it is important that the airport heavily dependent on the current situation in the tourism industry would not abandon the spatial agreements needed for implementing the overall vision of the structure plan.

ENDRIK MÄND is a practising architect and urban designer in offices Puusepp & Mänd and PEA Architecture Office. In 1998-2019, he worked in various positions in the Tallinn Urban Planning Department, the last 12 years as the city architect of Tallinn. Since September 2022, he has worked as the chief architect of Viimsi Municipality.

PUBLISHED: Maja 111 (winter 2023) with main topic Street Unrest