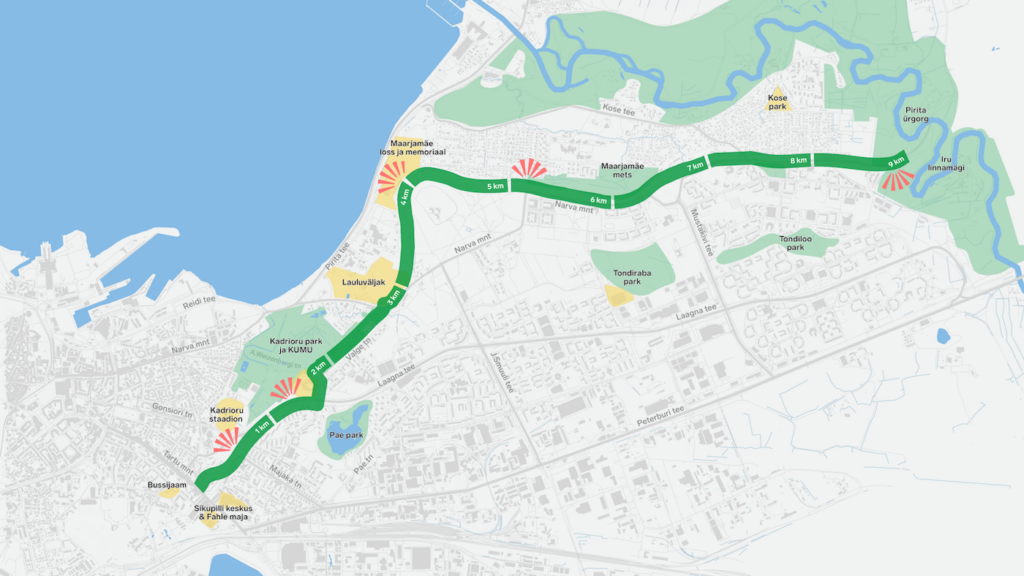

This summer, the city of Tallinn announced a landscape architecture competition for Klindipark. The purpose of the call for ideas was to find a comprehensive public space solution that would value the 9-kilometre-long limestone outcrop stretching through Kesklinn, Lasnamäe and Pirita districts, and that would function as a mobility connection between the districts, a park for spending leisure time, as well as a green network.

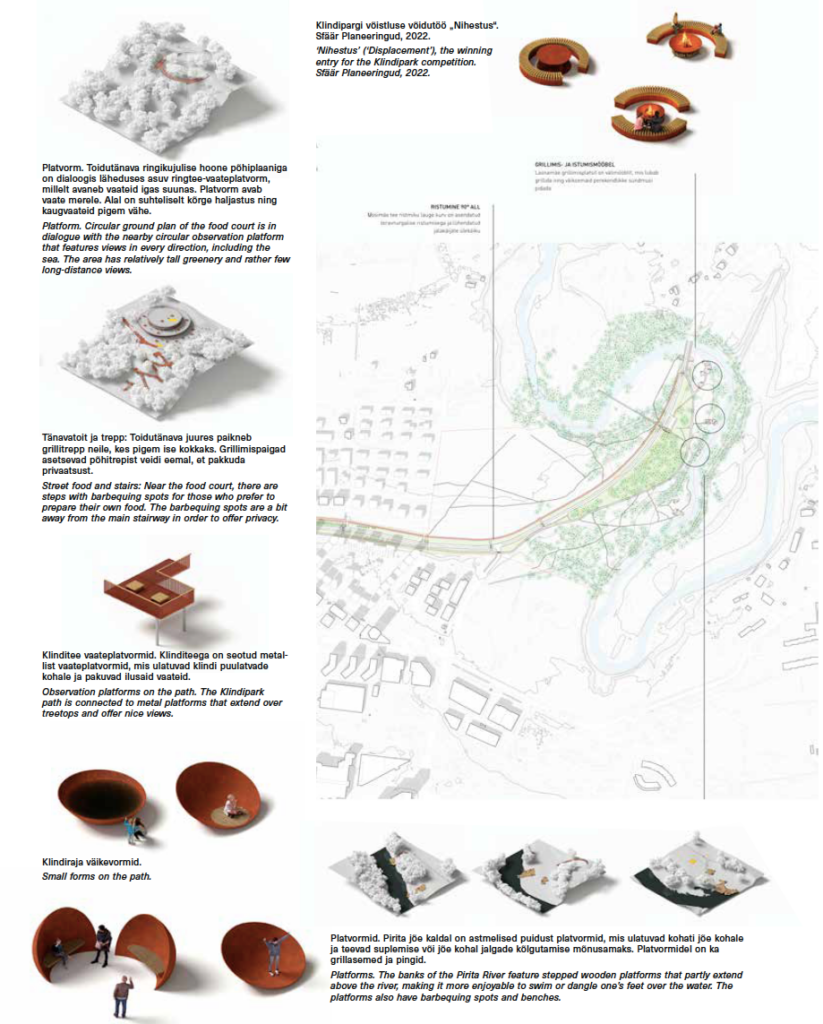

The competition was won by Sfäär Planeeringud (Kerttu Kõll, Lauri Läänelaid, Triin Kampus and Alvin Kanarbik) with their proposal ‘Displacement’. The work caught the jury’s eye with its comprehensive solution that offered not only a design idea for the park, but also ideas on how to tie the urban space around the park with the new green movement trajectory, and how to reduce noise and air pollution in the city.

I was asked to comment on the winning proposal from a biologist’s perspective. I have been researching urban nature-related issues for almost ten years now, and putting this knowledge into practice in the last couple of years. This experience has given me an understanding of what people value when it comes to urban nature. Natural scientists, for instance, appreciate first and foremost the intrinsic value of nature. A different view centres on the benefits provided by nature, such as clean air, the opportunity to spend time in nature to improve one’s mental and physical well-being, regulation of the water cycle and other biogeochemical cycles, and clean food. Urban environment, home to an increasing proportion of the population, is particularly one in which we need to be able to state very clearly and appreciate the benefits that nature can offer.

When I read the brief for the Klindipark architecture competition and the description of the winning work, the natural scientist in me was able to rejoice—both the idea and the solution of the linear park saw value in nature-in-itself, but also highlighted knowingly the benefits that city dwellers could gain by spending time in that environment. Nature itself, too, surely gains from a well-thought-out city park. Semi-natural ecological communities that function under constant and conscious human influence can provide valuable habitats for many species. This is attested, for instance, by the wooded meadows of Matsalu National Park, which are among the most species-rich in the world. The winning work of the idea competition for Klindipark is likewise noteworthy for its thoughtful design of semi-natural ecological communities—it involves plans to create wooded meadows, restore alvars, carry out tending and thinning. This is human impact on nature at its best.

Lack of awareness can mean that the human eye is not always able to recognise what is good for nature. Can we see value in fallen and rotting tree trunks, which are actually much more full of life than living trees, providing habitats for decomposers such as fungi and bacteria, but also lichens, mosses and various insects? These are in turn fed on by birds, bats, hedgehogs. The winning proposal for Klindipark emphasises precisely the creation of such habitats. My own recommendation with regard to such elements would be to make use of them in nature education. Why has this trunk been left to lie here? How does it sustain the surrounding ecosystem and cycles of matter? A fallen tree trunk should not strike the passersby as negligence or disorderliness, but rather delight them with its biodiversity-supporting abundance of possibilities.

In these days, people often need to be reminded even on a hiking trail to stop and take some time to examine the surroundings. In the winning proposal, such gentle signals to stop are provided by small forms on the path—3-metre-diameter disks. The design proposal ingeniously places some of them upright and others horizontally; sometimes, they are supplemented by wooden platforms for sitting or lying down, whereas in other places, they are filled with water. Looking for and finding the disks could even be a kind of orienteering game for those strolling along the path, with the prize of getting some rest from the urban hustle and bustle.

When it comes to the social aspects of urban nature, many studies have highlighted inequality: it is mostly the affluent who have better access to nature and its benefits. Nature, however, is a common property of us all, and wallet contents should not determine whether people have the opportunity to invigorate their mental health in a natural area close to home, or whether children are able to pick berries from a bush or play in a clean, species-rich environment. Klindipark, which does not distinguish between less and more prestigious districts in its course, offers all of that to a great number of city dwellers—everyone is welcome and everyone has equal access to picnic spots, walking paths or even the food that is growing in the nature there. The winning proposal foresees that the current wasteland, which has come to accommodate spontaneous landfills, will be replaced with food groves. This will provide support for natural species such as pollinators, but also a direct link with the benefits of nature—clean food from clean nature.

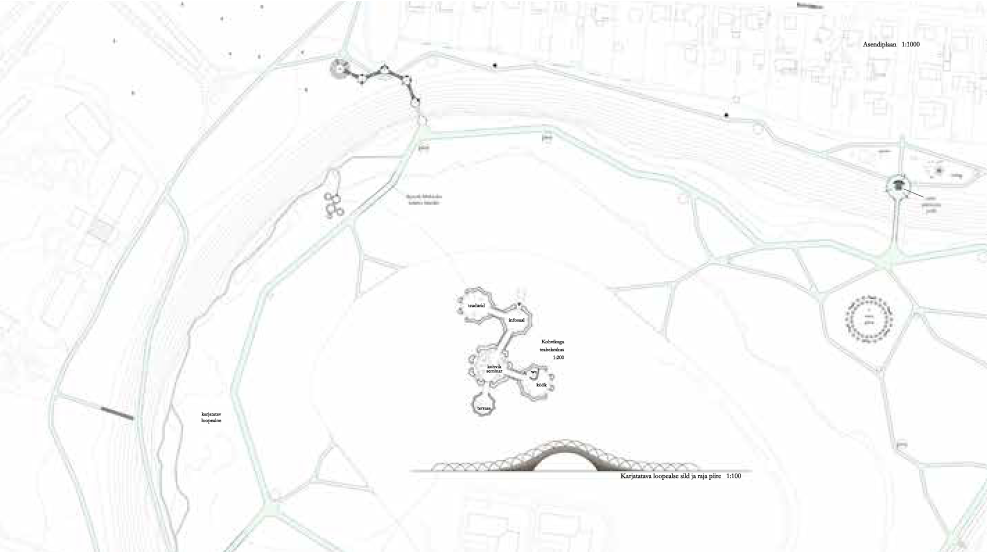

To the centre of the park, architects have planned a round two-story building, the lower level of which could function as a food court and the upper level as, say, a library or a community space. This provides an additional reason for people to come to the park, move on foot, spend time in nature. One exciting solution is the large spiral ramp with an adventure park planned in the middle. Once again, an inclusive approach can be felt—the lower part of the adventure park with easier trails is open to everyone, whereas trickier bits that require extra safety are administered by a specialised company. A circular path raised to the treetops is a thrilling idea and offers people an opportunity to take some time off—why go straight, when you can go round! However, the option to go straight and go quickly is also there. ‘Flexibility’, ‘inclusivity’ and ‘freedom of choice’ are the keywords that come to mind with each and every page when reading the winning project.

Another fascinating architectural solution in the proposal consists in the stairways that lead down the steep slopes of the outcrop. These stairs, however, are not only for moving up and down—they are integrated with viewing platforms, slides, playgrounds, even some tiny private pockets for having a barbecue or picnic. The architects of Sfäär Planeeringud have tied together playgrounds and picnic sites in a way that those with families can immediately recognise as skilful and knowledgeable. Children do not want to sit around and enjoy the view—they want to play. Spending time and bustling about in nature is an efficient and scientifically proven way of alleviating mental health problems of children and youth. Klindipark can be seen as an investment in what is dearest to us—our children’s mental and physical health.

The authors of the winning work have emphasised mitigating the effect of Narva hwy—a physical boundary that hinders access to nature—as one of the most important elements in their solution for Klindipark, and this aspect was also noted by the jury. In order to mitigate the boundary, motor traffic on Narva hwy will be slowed down with smaller turning radiuses, raised crossings, safety islands and green median strips. Densely placed crosswalks prioritise the pedestrian, while green median strips tie the park seamlessly with the surrounding urban space. The winning work shows how city traffic should be organised in the future—people first, and only then the cars. It is an extremely smart and thoughtful solution that foregrounds people’s mental and physical health. It does this by improving their mobility options, but also by bringing down air and noise pollution through reducing traffic loads and speeds.

Although we are prone to bemoan the low diversity of the Estonian landscape—we don’t have any great mountains or canyons, volcanoes or rapids—we should open our eyes instead to notice and value what we actually have. A protected limestone outcrop that stretches through three districts of Tallinn is an incredibly awesome opportunity for both citizens and tourists. The idea competition for Klindipark with its winning proposal is a forward-looking, ecologically sensitive and well-thought-out homage to Estonian geology and our coastal landscapes. If the city could niftily tie the proposed solution to nature education, it might able to instigate the development of a new kind of city dweller—the kind that is able to appreciate the value of nature-in-itself as well as the benefits offered by nature. This is the only way to realise that nature in urban space is a solution rather than a problem.

TUUL SEPP is an Associate Professor in Animal Ecology at the University of Tartu, whose research focuses on the impact of man-made environmental changes on free-range animals. Tuul was awarded the Young Scientist Award in 2020 by the Cultural Foundation of the President of the Republic.

HEADER photo by Paco Ulman

PUBLISHED: Maja 111 (winter 2023) with main topic Street Unrest