THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY CENTRE

Location: Punane 68a, Lasnamäe district, Tallinn

Architecture/idea: Ivo Heinrich Arro, Paco-Ernest Ulman, Spatial Design Competence Centre of Tallinn Strategic Management Office

Commissioned by: Circular Economy Department, Tallinn Strategic Management Office

Total area: ca 4500 m2

Project: design development begins in 2023

Completion: planned in 2025

Current stage: The vision is for application of design provisions, gaining the land from state ownership to municipal ownership and proceeding with the design process.

Municipal authorities are obliged by law to manage separated waste collection in a way that would best enable preparation, recycling or other kinds of reuse. The circular economy centre project that is led by Tallinn Strategic Management Office, however, is much more ambitious. In addition to managing separated waste collection, the purpose of the project is to de-stigmatise the culture of reuse and recycling by focusing also on educating the society.

Public architect as a spatial designer

The circular economy centre highlights the potential of waste materials as a reusable resource. It creates possibilities for repairing, reprocessing and using things again. In order to achieve this, the project involves architects from the Spatial Design and Planning Department of Tallinn Strategic Management Office who helped to lay down a vision that would look at waste management from a new perspective. The vision is the basis for the public processing of design provisions, which will be followed by the design process.

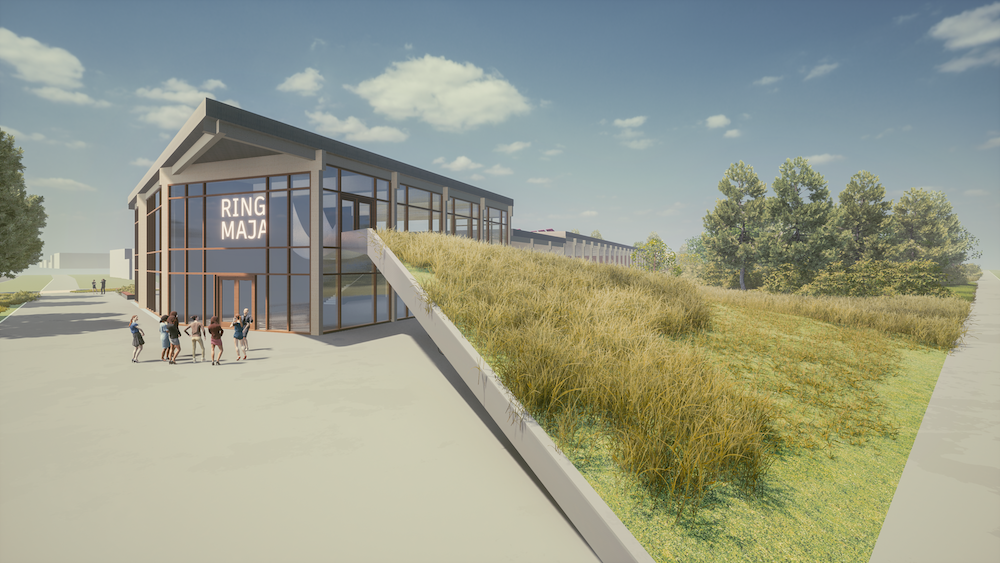

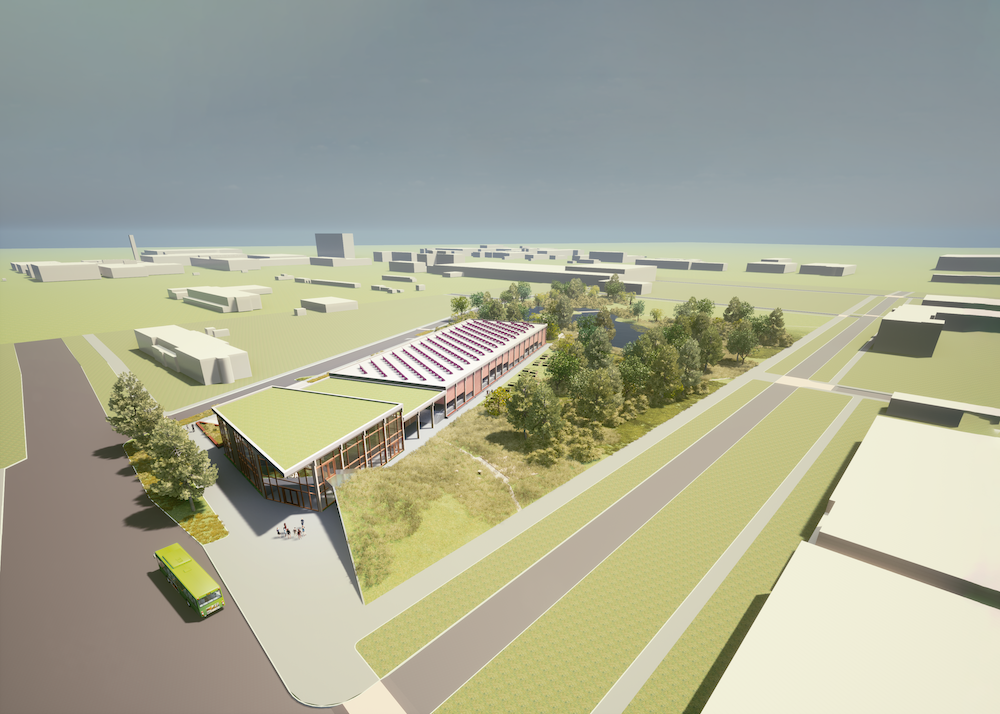

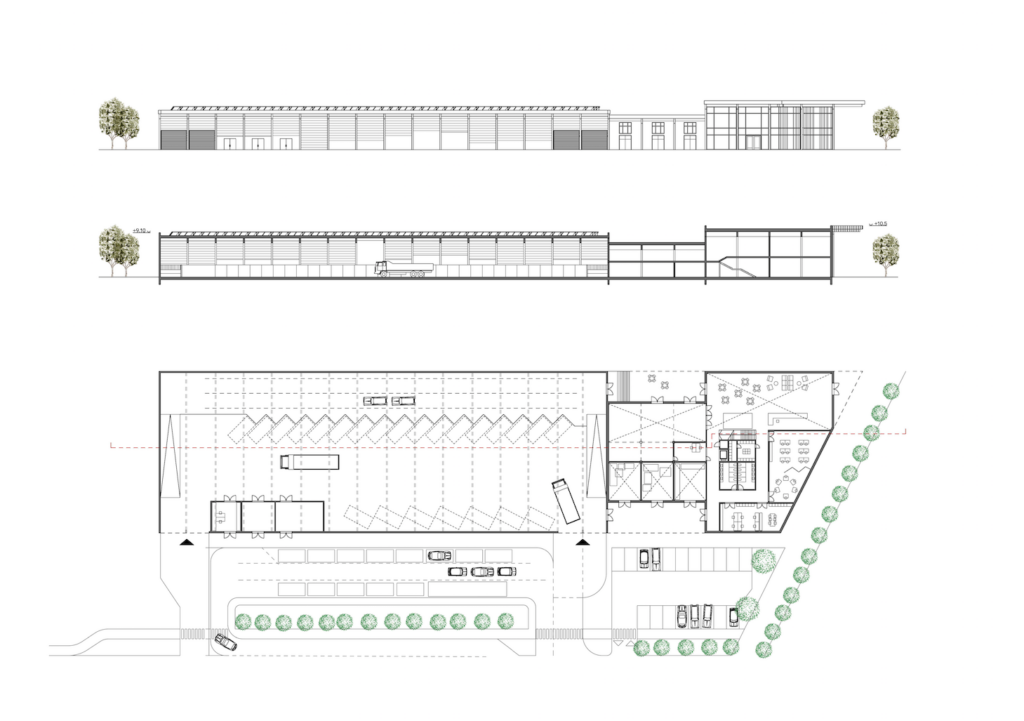

The circular economy centre that is being planned to Lasnamäe, Punane st 68a, is a new type of waste management facility. The first part of the building is situated by Punane street and consists of classrooms, working rooms and reuse rooms. The second part—waste repository—lies on a prospective new street, a little bit further away from the main street. The two parts are conjoined by a block of various workshops.1 The circular economy building should wear its title well, drawing attention to the trouble spots of the prevailing consumer society. Consumption that has been made too fast and too easy has increasingly pushed the reuse and repair culture aside. It has become a habit to throw a broken item away rather than to look for a repairman with the necessary skills to make it usable again.

City as a material bank

The earlier and still dominant conception of circular economy revolves around waste management. Awareness of the necessity of separated waste collection and its management has indeed grown over the last years, and the practice of waste sorting has reached many homes, but on a larger scale—e.g., in the construction sector—things are still in their infancy. Used materials and objects still have a more negative ring to them than new and fresh ones. Given the current reuse market where the main sales platforms are various online marketplaces, it is more convenient to prefer new things. Online marketplaces have not worked out regulations for assessing the condition of an object, and hence there are no guarantees for the buyers of old things. A circular economy centre essentially offers an organised platform for mediating waste products, bringing together their collection, organisation, sprucing up and reprocessing. The main goal is to extend the life span of products, thus increasing their value. In sum, this helps to make the whole value creation cycle more economical by making businesses less dependent on the price fluctuations of raw material markets.2 This approach supports a business direction where importance lies in services rather than products.3

Observing the principles of circular economy in built environment foregrounds the principles of sustainable construction, such as demountable design, evaluation of product lifecycle, and adaptable, flexible and open architecture.4 In architecture, circular economy is associated with the cradle-to-cradle design conception, which aims to treat cities, buildings and materials as part of continued biological and technological cycles. Design relies on an information system that gives an overview of available materials. This in turn requires systematic documentation of materials—materials passports, examples of which can already be found in several European countries.

In architecture, circular economy is associated with the cradle-to-cradle design conception, which aims to treat cities, buildings and materials as part of continued biological and technological cycles.

A new circular reality

Strategies to introduce reuse and recycling have been developed in a number of European cities. In Vienna and Berlin, for instance, people leave their used furniture on the street, where it quickly finds a new owner. A more systematic exchange has been developed in Copenhagen, where the cityscape is dotted with small shed-like collection points to which citizens can bring their old things and others can grab what they need. In addition to these, approximately 20 larger and smaller waste management facilities are also scattered around the city.5 Half of them can be accessed on foot and the other half are designed for bringing larger refuse by car. In Tallinn, there are currently 4 larger waste management facilities, 6 hazardous waste collection points and also approximately 60 collection containers for utilisable clothes. Compared to Copenhagen, the chance of coming across a waste management facility is several times lower, and usually it needs to be accessed by car.

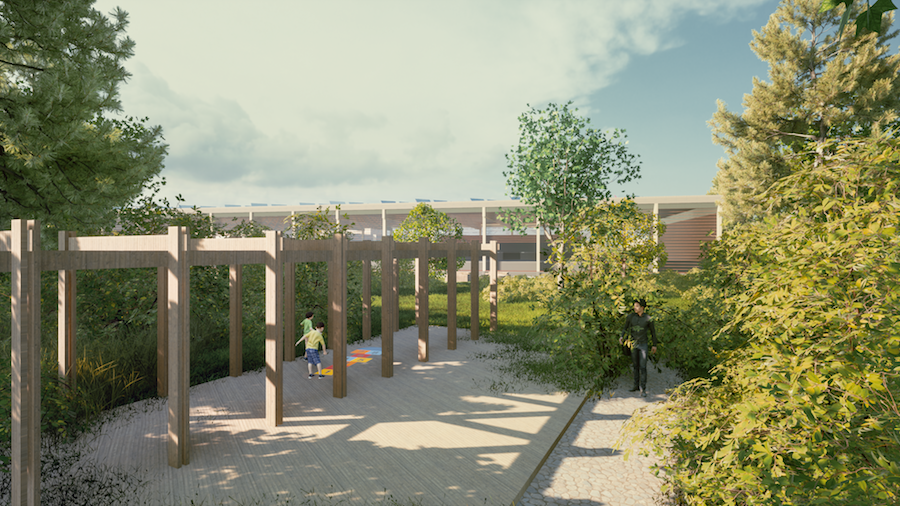

In the context of Tallinn, the Lasnamäe circular economy centre will have a good location—there is production, high population density and several social institutions in the area. The entrance from Punane street to the circular economy centre features inviting architecture and an open atrium, making the building easily accessible to everyone. Contrary to the traditional conception, which foresees that waste is placed somewhere out of sight, an important aspect of the prospective circular economy centre is its proximity to people that helps to normalise the culture of recycling and reuse. Since the principles of circular economy state that it is beneficial to attribute a larger number of uses to an object, this should also hold for the circular economy centre itself. The space should be designed in a way that would be easily adaptable and enable cross-use of rooms.

The described spatial strategy that adheres to the ‘principles of openness’ should also apply on a larger scale of planning. New waste management plants should already be built as circular economy facilities; the earlier name that mentions waste should be dropped as obsolete. Being located on people’s everyday trajectories is of vital importance. Convenience plays an important role—giving new life to materials should become as easy as throwing them away. At the moment, only the containers for used textile products are handy like that right on the street, but this kind of convenience should extend to all sorts of products and materials. A system of both major and minor opportunities for reuse should form a cohesive part of the urban fabric in order to turn observing the principles of circular economy into a natural thing. In principle, smaller circular economy centres could replace, say, at least half of the current parking lots, which can be found everywhere in the city. This would let us speak of an environment-friendly city that has created a new social structure in the form of centres that offer various interesting activities.

Creator of community

The typology of circular economy centres could essentially be equated with basic services in an urban space such as kindergartens, schools, apothecaries or community centres, all of which bring people together. In the case of Lasnamäe circular economy centre, community development is fostered by classrooms and workshops. Supervised open workshops present an opportunity to acquire skills in repairing and fixing up things and materials. The stigma carried by the term ‘waste’ must go.

In the future, a system of circular economy centres could offer communities an opportunity to take part in the construction industry. Use of circular materials raises the issue of their storage, which is something that namely local residents could help with. A system of distributed storages can provide an alternative to warehouses that are standardly planned to the outskirts of the city. In order for the system to function, constant administering of the inventory by the community is needed. If the respective platform would be properly developed, communities would be able to provide an alternative to hardware stores that sell only new materials.

In Estonia, there have been warehouses for old materials in Paljassaare subdistrict of Tallinn and Paide. The Paide unit of the Information Centre for Sustainable Renovation (SRIK) also created an online platform for collected materials, but did not get all the way to distributed storage. Unfortunately, Paide SRIK has ceased its activities by now, and thus, the necessary practice has been paused. But Rainer Eidemiller who used to lead the unit says that distributed storage has great potential for community building.6

Building and working with existing materials requires a new kind of approach where the material begins to dictate what can be built and how. Materials bought from the hardware store meet all the standards, and working with them is quite easy to imagine. Reused materials, on the other hand, have their own histories and peculiarities, and their fit with other materials often becomes clear only at the construction site. Architects who use pre-existing materials need to be much more up to date about what they are working with—they need to know the properties and special features of the materials. This might lead to the emergence of a new kind of hybrid specialist at the intersection of architects, engineers and heritage protectors. The substance and starting point of their work would be pre-existing material. The purpose of circular economy centres is precisely to bring materials closer to us, and make working with waste materials a part of our everyday lives.

HELENA RUMMO and ELINA LIIVA are doctoral students in Architecture and Urban Design at the Estonian Academy of Arts. Their work explores ways for utilising resources found in the city more efficiently through reuse and collective action.

PUBLISHED: Maja 111 (winter 2023) with main topic Street Unrest

1 Spatial Design Competence Centre of the Tallinn Strategic Management Office, Sketch of the Circular Economy Centre at Punane 68a, May 2022.

2 William McDonough, Michael Braungart, Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things (New York: North Point Press, 2002)

3 Harri Moora, „Ringmajandus“, Diskreetne loodusteaduste õhtukursus, Energy Discovery Centre web lecture 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KpU1_oV9vf4.

4 Urszula Kozminska, „Circular Economy in Nordic Architecture. Thoughts on the process, practices, and case studies“, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 588 (2020): 2.

5 Waste stations managed by Amager Ressourcecenter and their locations: https://a-r-c.dk/privat/find-din-genbrugsplads/

6 In conversation with Rainer Eidemiller