The sedimentary layer of Estonia deserves valorisation, conclude the material development and design studio kuidas.works. Maria Luiga and Hannes Praks write about their recent earth-based construction study trip to Paris.

In his book Visions of Jazz: The First Century, American jazz critic Gary Giddins describes the fundamental difference between classical music and jazz: the former values strict fidelity to the notes written by the composer with musicians aiming at playing the composition as closely as it has been written. Jazz music, on the other hand, is characterised better by the interpretation of the written notes and the cooperation between the musicians: the individual interpretation and improvisation by musicians are assigned greater value than the adherence to the initial notation.

Musicologist Leo Normet outlines the historical reason for the complexity of notating jazz music: namely, due to slave trade, jazz music is influenced by the pentatonic or five-note scale without semitones from the West African coast that was adapted to the Western seven-tone scale. It results in a compromise between two scales called a blue note. However, even in the compromise solution, there is still a degree of confusion when particular pitches coincide. Estonian musicians call such a mismatch the Cuckoo’s Third.

The Cuckoo’s Third occurs also in building practice relying on recycled materials where it is the rule rather than the exception. We are constantly faced with situations where, due to the great variety of raw materials and the dynamism of the process, the ambitions of the contemporary sustainable and circular construction do not coincide with the capitalist construction model. If we add to that the dimension of location-based geosourcing,1 it will get even trickier. Therefore, contemporary concepts such as urban sourcing and geosourcing need an adapted system, a kind of a blue note.

Researching contemporary building methods in the local frame of reference (so-called local tech), the material development and design studio kuidas.works took a quick trip to Paris this spring. The aim was to visit practices specialising in the development of circular materials in their local context. The thickness of sedimentary rocks, including the layer of clay is considerably greater in Central Europe than in the Nordic countries, thus, France and Belgium are at the forefront of soil valorisation practices or earth-based construction in Europe. But just as bees are kept and strawberries grown in Estonia despite the short summer, so it is found by kuidas.works that Estonia’s thinner sediment layer also deserves to have added value.

The focal destinations of the trip included the micro-factory Cycle Terre (‘soil circulation’ in translation) turning the clay soil excavated from the construction of new underground lines into building blocks, and the architecture studio Ciguë with extensive experience in circular material development.

Tuesday, March 21st

8:34

The day begins with a bike tour in Paris. One of the founders of Koz Architects Nicolas Ziesel meets us at La Plaine – Stade de France railway station in a yellow raincoat with the following greeting:

‘Welcome to the weirdest spatial experiment in Paris. Only recently, there were cosy and popular human-scale cafés in the middle of the square surrounded by tall office buildings near the station. Then, all of a sudden, the cafés were demolished and there were only the modern office monsters overlooking the empty square.’

9:55

The destination of the bike tour was Koz’s temporary CNC studio making interim use of the lobby of a building under construction to produce furniture from recycled wood for the food street built next door.

‘We bought a CNC mill for the project which at only 25,000 was pretty cheap. The crates we got from a company specialising in transportation of artworks and they are made of high-quality plywood. The company arranging the transportation is usually responsible for getting rid of the crates and often they are merely burnt. We decided to make the interior of our new project entirely out of recycled crates. The client finds it highly important that the crates are manufactured in the same district as the food court and made from sustainable material,’ Nicolas explains the background.

The formula is simple but likeable: the dimensions and shape of the furniture elements are configured on the basis of the original crate dimensions in order to make the most of the idea of material circulation and deviate from the traditional mass production formula.

14:20

We get off the train in the Sevran neighbourhood. There is a high fence next to the station and from the gate we can see a deep hole with excavators scraping brownish clay soil at the bottom. We continue to walk for about a kilometre and find ourselves at the entrance of one of the most remarkable local-tech projects in Europe.

It is Cycle Terre—a factory of unburnt bricks made from local raw material. Their beautiful new manufacturing facilities are constructed on a glulam structure combined with particle boards, unfired bricks, plywood and steel. It is thus marked by the qualities of both a permanent and a temporary building. We peek through the polycarbonate wall on the second-floor balcony how the bricks coming out of the Flexiterre press are grabbed by an ABB robotic arm performing non-human choreography.

15:00

A lecture starts in French on the company’s establishment, operation and further development. We try to use Google Translate but it results in a somewhat psychedelic text on construction with no sense whatsoever. When appropriate, we ask one of the students if she is willing to share her notes with us. Thanks to this and the tour of the factory after the lecture, we are considerably better informed.

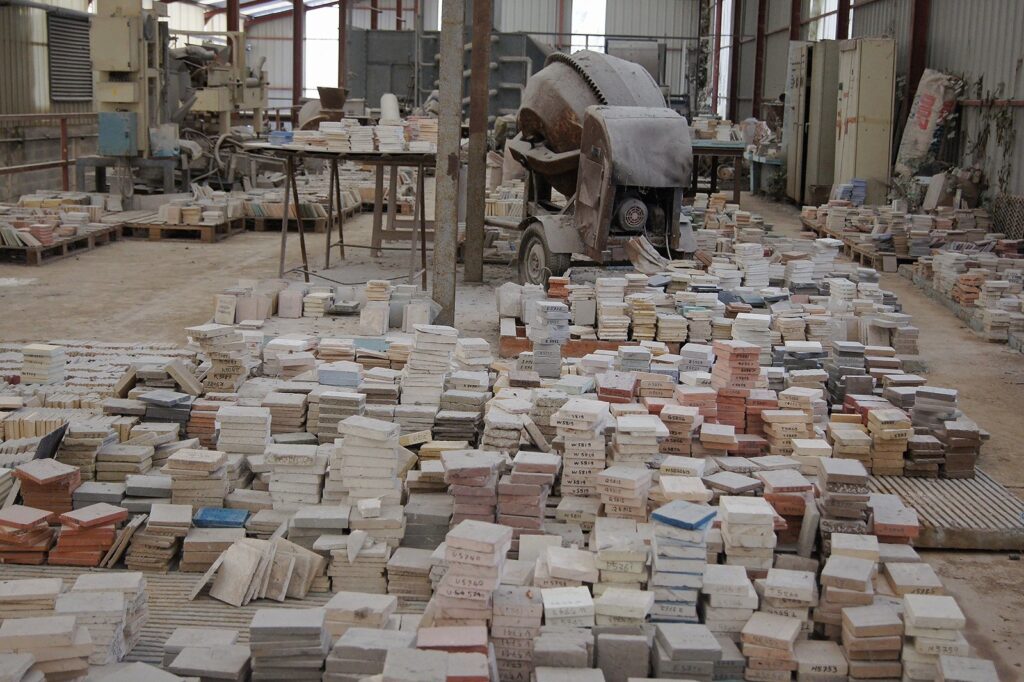

Founded in 2018, Cycle Terre is one of the leading European companies turning soil into building materials. The geological distribution of the French soil is favourable for forward-looking building solutions, in other words, it is very clayey. In addition to other construction activities, also new underground lines are developed in Paris, including the excavation of around 450-500 million tons of soil, that is, potential building material by 2030. Cycle Terre specialises in the production of compressed earth blocks and clay tiles. Compressed earth blocks usually consist of three main components (clay, sand, gravel) produced by adding water and applying mechanical pressure. When the water evaporates, the earth block hardens and gains its strength. When coming out of the press, the blocks’ compression strength is at least 5 MPa, rising to 6-7 MPa once hardened and 8-12 MPa in a stabilised earth block (with 5% cement added). The advantage of compressed earth blocks is their infinite recyclability while some stabilisation adds considerable compressive strength and resistance to moisture. Cycle Terre uses only clay soil from Paris as raw material which forms the basis for various building material recipes. Rainwater collected from the roof of the building is used to prepare the mixture.

The information given on the tour is a clear reflection of a rapidly growing sector. In 2022, 80,000 earth blocks were exported for various projects while already 450,000 blocks were exported by March this year alone. The popularity of the topic was also evident in the number of participants: there were factory tours every hour with altogether 40 people joining our tour with most of them students of structural engineering and architecture. The next day, we come back to the topic at the office of Ciguë discussing if architectural education in Europe is ready to support the construction industry’s changing focus. Camille, our partner in the conversation believes that the interest of young people in their twenties in sustainable materials is considerably greater than the discourse offered on them at universities. It is understandable as the current paradigm shift is faster than the ability of universities to provide lecturers with corresponding mentality.

We approach the factory manager and attempt to converse in English.

‘May I ask a question in English?’

‘Uuh … very slowly’, the manager replies.

‘Do you dry the earth before mixing it with sand?’ we ask.

When fitting the pieces of information together later, it becomes clear that the clay is indeed dried before the final mix is made. The shelves on the wall are full of building blocks of a pleasant brownish hue and slender proportions weighing 4-8 kg. We type a question on the iPad screen to be translated by Google, ‘Can we take one block as a souvenir to Estonia?’ ‘Oui’, is the brief response.

The next day, the block is confiscated at the airport security check as a legitimate hijacking tool. The seized block immediately catches the attention of airport employees. Stuffed in a yellow plastic bag, it is passed around, sniffed, and examined, they wonder about its weight and eventually test it for drugs, just in case.

The tour at Cycle Terre is thorough and exciting. It is obvious that it is not a standard business operation focusing on sales and manufacturing with no attention paid to the production environment. We clearly see that the entire building complex has been developed to promote a new technology, however, the production figures as well as visitor numbers show that the company is a success.

Wednesday, March 22nd

8:05

We set off for the architecture office Ciguë. As we fly back in the evening, we need to carry all our luggage, including the souvenir blocks received at Cycle Terre. This kind of a ‘block run’ allows you to get a pretty good understanding of the essence and weight of the material. We get to discuss the relations between carrying and understanding the material in the context of increasingly digital education and architecture practices.

9:28

We are in the Montreuil neighbourhood looking for Ciguë’s office among detached houses. At the gate, we meet a young Frenchman arriving at work asking, „Le rendez-vous?“

9:30

We are ushered into a small meeting room on the second floor with a terrazzo flooring. A sample piece of the same material is used on the desk as the base of Logitech webcam. Our host architect has not arrived yet, so the company is introduced to us by one of the founders Camille Bénard. We stay in this meeting room for an unexpectedly long time: lasting over two hours, the conversation is comparable to the best academic seminar which sincerely and deeply pleases the group that had waited for a formal one-hour information session.

Camille explains that it was decided to build the office from recycled materials with part of it obtained from the demolition of the former building on the site. He emphasises that it was a difficult decision: every time you unbuild something it is important to consider it carefully and weigh the possible consequences: could the existing building be used in part or in whole? Could it be rebuilt to serve the new purpose better? Could the materials of the building be reused in the new structure? He also gave an example that the cost of sending the waste off or separating it is the same as renting a crusher and reusing the materials again in the project. The above-mentioned terrazzo actually consists of pulverised and recycled brick and reinforced recycled gypsum powder. Talking about the afterlife of building elements and materials, we come to coin the concept ‘jazz architecture’, that is, architecture with its central axis formed by the inseparability of construction and concept, needs-based improvisation, flexibility as well as trust and close cooperation between the participants.

16:12

Waiting for our flight back to Tallinn at the airport, on the shelf at the sandwich and news-stand, we notice an issue of the architecture journal Architecture d’Aujourd‘hui (in English ‘The Translation of Today’) focusing on building locally. It covers all the topics discussed during our trip one by one: the cautious attitude to demolition, decentralised design practices, circular material sourcing, geosourcing and also a more extensive article about the Cycle Terre factory. It is a fittingly meaningful and yet casual conclusion to the trip.

To sum up

France has the ground, both literally and figuratively, to promote and implement sustainable building techniques in contemporary building culture. There is also good clay soil in Estonia but the view taken by our construction and architectural sector is still considerably different from that of the pioneers in France and Belgium. Excavated soil is still considered waste that is simply transported from the construction site by trucks to be used as land fill elsewhere. The same could be said about other construction waste and rubble, for instance, gypsum, clay bricks or concrete. Although the latter is now used as filling in roadworks, it is a case of downcycling, a process where the material seems to be recycled but it is first crushed which destroys its strength properties and possible reuse in the future. It is this kind of research and recommendations in this climate, geographical location and cultural space that kuidas.works has been dealing with since 2021. The studio is currently located at the lab established in cooperation with Tallinn University of Applied Sciences where we prototype building materials and organise public workshops.

MARIA HELENA LUIGAis a founder of kuidas.works. She studies at the master programme in architecture at the Royal Danish Academy. HANNES PRAKS is a founder of kuidas.works and the newly elected chairman of the Estonian Centre for Architecture.

HEADER photo by Päär Joonap Keedus

PUBLISHED: Maja 112 (spring 2023), with main topic Moratorium

1 Geosourcing refers to a practice where the excavated soil is used as a construction material in the building above it. In other words, soil is considered as an actual building material.