Prior to the 20th century, the interior linings of finer homes were typically done by professional upholsterers (most of them men) in collaboration with architects. However, around the turn of the century, the job of dressing the interior shifted towards becoming a job more often done by women. At this time, a modernist idea of ambiguity between interior and exterior emerged, which led to an understanding of the interior as a by-product of the overall architecture. This was in contrast to previous times when interiors were equally important to, for example, the design of facades. Now, interiors became something that could be decorated afterwards. Coinciding with interior design becoming women’s work, interiors as part of the architectural project began to take an inferior position to capital A architecture.1

The association between women and home was first theorised in architecture in the Italian Renaissance when the work of the architect as we know it today was founded. For example, as Mark Wigley has put forward, Alberti’s writings stated a clear hierarchy between public and private spheres with women belonging to private domestic spheres.2 In the U.S., feminists from mid-19th century till the early 20th century were concerned with the home and its neighbourhoods, wishing to transform women’s domestic spheres as a part of the material condition of women’s lives. In the 1980s, Dolores Hayden described these ‘material feminists’3 who sought to negotiate women’s agency (or lack thereof) in housing production by re-positioning women as ‘active agents in spatial production rather than passive recipients’.4 Such thoughts have laid the ground for feminists’ occupation with the material and spatial arrangements of domestic lives. Today feminist spatial practices are (still) concerned with the in-use value and experience of space. The discourse is characterised by an approach that starts from the material and the social relations producing it, whereas material and social aspects are seen as intimately linked.

The domestic interiors in the Danish contemporary context have developed towards a complete lack of character and difference in their inflexible spatial planning and standard interior surfaces. Multiple factors of a marketised spatial production and profession are behind this. Today the typical (Danish) interior is so rigid that it can hardly be inhabited in more than one way. This is an issue in a plural society of more cultures and lifeforms and it may obstruct inhabitants’ presumed need for identity and belonging.

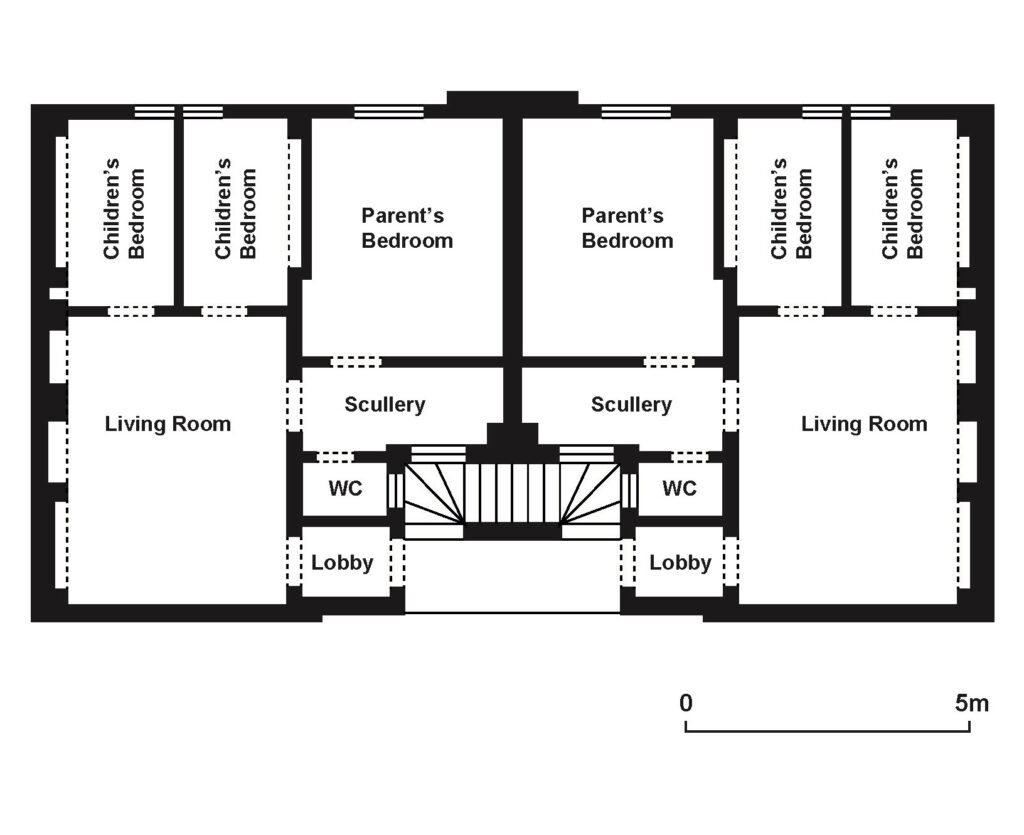

Author’s redrawing of floorplan after original from The Dwellings of the Laboring Classes: Their Arrangement and Construction; with the Essentials of a Healthy Dwelling, published by the Society for the Improvement of the Labouring Classes, London.

Built as a prototype for the Universal Exhibition in London in 1851, the British architect Henry Roberts’ housing model was to become a starting point for the interior configuration of homes in multi-story housing. This archetypical model resembles the organisation of typical Danish interiors today by the way it choreographs social relations in separate one-door rooms, setting a hierarchy between the members of the self-sufficient nuclear family. In this housing model, two flats share one staircase landing, described as the ‘two-per-floor’ theme by Irina Davidovici.5 Henry Roberts’ model was introduced for the labouring classes6 by the British state and later Roberts’ catalogue of home configurations for the labouring classes was disseminated across Europe. The reason for the success of this specific type is that, even if the prototype was only built as a two-story building of four flats in total, the logic of the plan, with its windowless gable ends meant that it can easily be added to horizontally and stacked vertically. Robin Evans has explained how Roberts’ model homes represented the so-called morally correct lifestyle for the labouring classes of the time and were developed and disseminated by the state. Evans has further argued that such arrangements of people into gender and family groups as well as class can be seen as oppressive.7

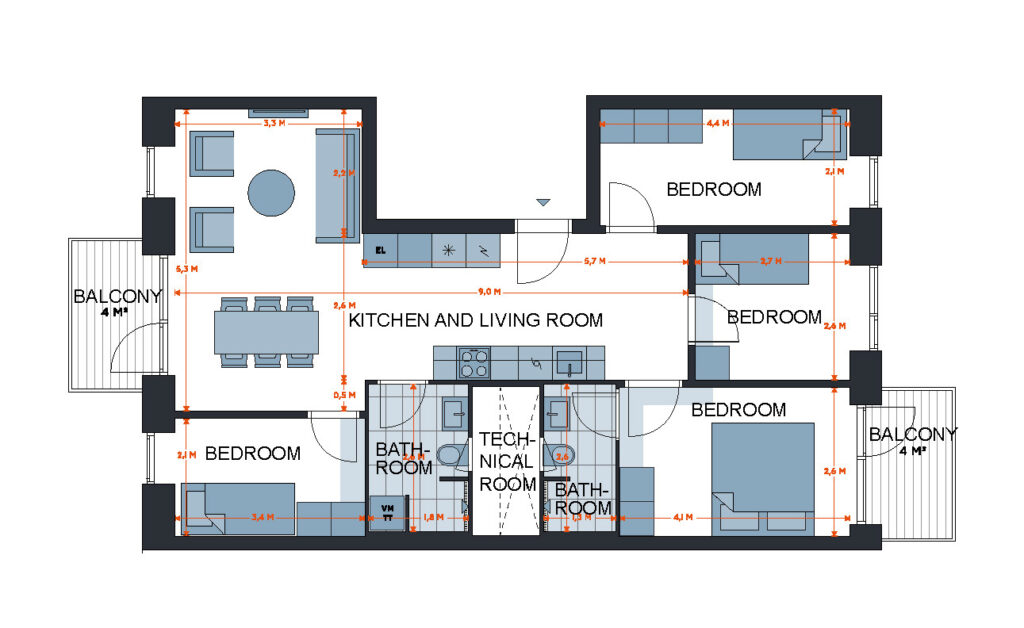

The typical Danish interior in multi-story housing can be recorded in the example of Fristrup Hus.8 The floorplan largely follows Henry Roberts’ housing model: the two-per-floor theme is used here, and bedrooms (one larger than the others) are all accessed by one door. However, it differs from Roberts’ model by combining the kitchen space with the living room. This is what is typically called an ‘open plan’ and in real estate brochures (where this drawing stems from) it is often marketised as ‘open plan living’. Yet, this is not a Corbusian open plan or like an early modernist example of flexible open plan living, but more so a compromise between a cellular plan type for the privacy of the individual with an open connection between kitchen and living room which is a way to economise built space and hence maximise profit for developers. When taking a closer look at this typical plan, seeing how rooms are dimensioned and how doors and windows are positioned, it becomes clear that furnishing this home can hardly be done otherwise than as shown. While leaving little room around a standard set of furniture, bedrooms are so tightly configured around the equally tight-fitted functionalist kitchen and living room. When each bedroom represents a dead-end, movement around the flat is restricted and inhabitants have few options to furnish otherwise than as shown in the sales brochure. Perhaps ‘open plan living’ is in fact not-so-open.

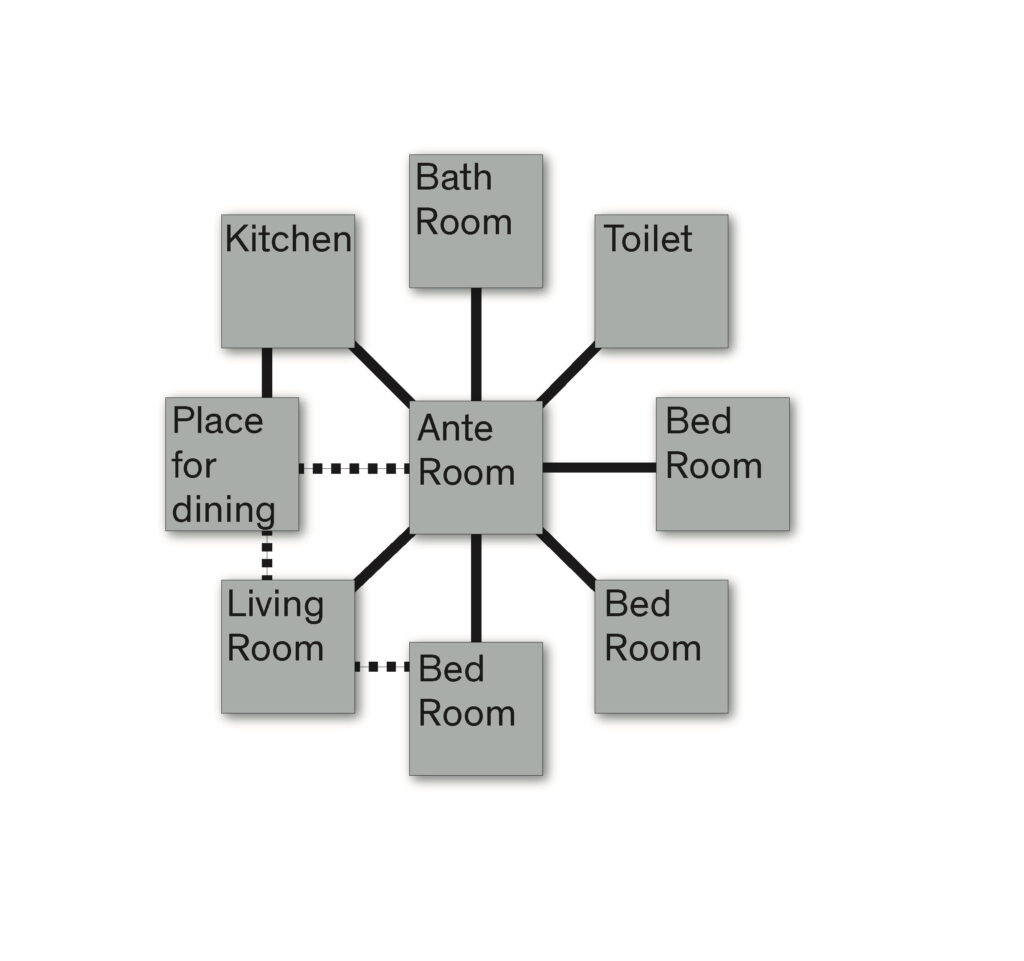

A diagram shown in a Danish housing design guide for multi-story housing from 1967 depicts another way of configuring rooms.9 It is a guide to designers for best-practice room connections, suggesting rooms with more than a single connection. It makes use of a room type that has completely gone missing from today’s spatially optimised floor plans—the ‘ante room’. This room type is, as explained in the guide, both an entrance space and an additional living or dining room, and in general, it provides the flat with more separate rooms for socialising. To add to this, the recommendations for room sizes are larger than the rooms shown in the typical Danish flat of today. As an example, in 1967, double bedrooms should have been at least 11-13 m2. Additional spaces and slightly larger bedrooms are not only more flexible in use for the inhabitant but also welcome the uncertainty of future ways of living in multi-story housing, as it is thoroughly illustrated and described in the guide. As such the recommendations for Danish housing design of 1967 recommend more generous and flexible interiors than what has become the typical Danish interior today.

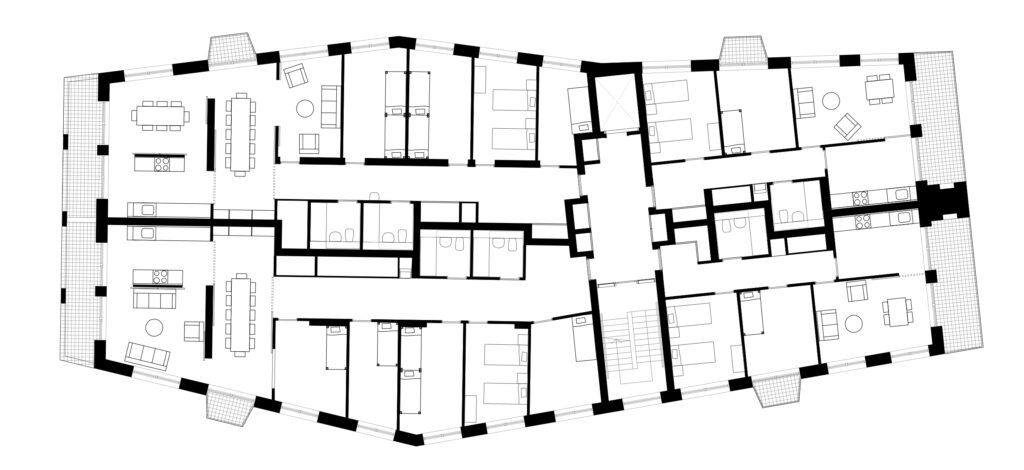

On the outskirts of Zürich, on Waldmeisterweg, the Swiss architects Lütjens Padmanabhan have designed an apartment block where the living room, bedrooms, and balcony are configured around a central dining hall. All of these surrounding rooms are of a similar but generous size, leaving it up to the inhabitant how to use the rooms. For example, as it was intended by the architects, the flats can be occupied by a group of students who may use the living room as a bedroom and only share the kitchen and dining space. The embedded balcony is shielded from the wind and dimensioned to also act as an additional living room on warm days. The front doors facing each other across staircase landings mean that, when doors are open, children can run between flats and into the so-called dining halls of the flats, as described by the architects10. Another quality of the floorplan is that most bathrooms are at the façade allowing for light and air to fill the room instead of the typical mechanical ventilation and artificial light. This is just one of many examples showing how Swiss architects are seeking to challenge the typical spatial planning of flats in multi-story housing. The rich Swiss housing design culture starting from educational cultures has led to high-quality interiors of Swiss housing, as it was argued in the online symposium ‘Five good Swiss plans’11.

The detailing of doors and surfaces in the Swiss housing on Waldmeisterweg are, unlike in the typical Danish flat, sensitive to various uses and give variation and character to the rooms. Some doors leading to larger rooms, such as the one seen here, have a floor-to-ceiling door, whereas other doors are lower. The tiled flooring of the dining hall with kitchen spills into the adjacent room, where flowerpots can be placed along tiled edges. Another idiosyncratic design solution is the imagined shadow cast onto the floor of the dining room of the terrazzo column, laid as a timber inset in the tiled flooring. The claddings of the interior surfaces are all low-key and non-exclusive. This approach has been described as a form of ‘hyper-normality’12 coming from the architects’ approach of putting ordinary materials and architectural elements together in unconventional ways, constructing a narrative, or referring to other architects both contemporary and historical. For example, bathroom tiles are low-cost small tiles mounted on a grid in alternating blue and white stripes. This colourful stripy surface adds a certain joyfulness to the bathroom, and as described by the architects, it is in line with the project narrative ‘a day at the beach’, with the stripy tiles resembling beach towels. The painted white timber cladding on the interior walls of the balcony equally alludes to beach houses and in particular to the ‘Lieb beach house’ by Venturi and Scott Brown13.

In London, Adam Khan Architects have designed a housing scheme that through adjustments to the floorplan of the four non-orthogonal building blocks, gives the interiors an opportunity for multiple uses. The homes are designed to also accommodate Jewish lifestyle as the local London neighbourhood is home to a large orthodox Jewish community—the entrance spaces are enlarged and provided with a sink where an additional kosher kitchen can be set up and most balconies have an open view to the sky for the sukkot season when festival pavilions should be built under open skies according to Jewish tradition. To add to the specific concerns for the local Jewish community, the homes in Tower Court are designed pursuant to the London Housing Design Guide14. This guide is used in many public housing projects in London. It stipulates minimum spatial requirements for homes that are usually more generous and versatile than typical marketised housing interiors. By not merely replicating the market preference and providing multiple flat types, the homes in Tower Court make room for people of different cultures and life stages.

The interiors of Tower Court are airy and bright in their generous and flexible design. The materials and detailing are simple and robust, and a red tiled floor marks kitchens and entrances. Double doors are in some places positioned to create an enfilade of rooms, and in other places allow for joining two rooms together. It is up to inhabitants to choose whether to use one of five bedrooms as an additional living room adjacent to the dining room connected via double doors, and balconies are positioned so they can potentially extend rooms (e.g., to make space for a larger dining table). The sliding doors along the façade give an opportunity to visually connect rooms while also allowing for the kitchen to be closed off. The majority of homes in Tower Court are socially rented, while some are in shared ownership and others sold privately. Nevertheless, all interiors are carefully designed. In Tower Court, the quality of the interiors far exceeds what is (sadly) often expected in social housing—in particular in the Danish context where social housing has for long been an under-prioritised discipline within housing design15.

Epilogue

To conclude, typical Danish housing and its marketised interior, which is currently being replicated in many new neighbourhoods of Copenhagen, arguably only supports one way of living for a stereotypical nuclear family. The domestic interior has gained a renewed focus in architectural discourses and feminism, however, a marketised mode of housing production restricts a fuller exploration of interiors in many contemporary housing projects.

In addition, the interior design of housing seems to be steered by a demand for comfort provided by technical appliances. This type of comfort is described by Adrian Forty who problematises how (technical) comfort is today seen as an end goal for the contemporary domestic interior16. Forty explains how in pre-modern times, comfort was a temporal notion of religious character, and thereby not only a bodily but also a spiritual state. This type of comfort being a changeable and subjective value is key to domestic interiors since it is hard to imagine the domestic interior as something that can reach a final state of total (technical) comfort. After all, architects’ and inhabitants’ homemaking processes in interiors happen over time and vary with inhabitants’ different cultures and life forms. Domestic interiors should contribute to inhabitants’ identity and belonging and cannot therefore be only a measurable end goal. The technically comfortable interior is tied to the stereotypical lifestyle images that are sold to us by the market, such as the questionable ‘open plan living’.

Feminist theory in architecture and spatial practices may be able to support a much needed shift away from the ‘paternalistic top-down model of mass housing’17 producing the marketised interior. Or as the feminist thinker Donna Haraway has suggested, we must cultivate ‘response-ability’ through knowing and doing together18. To move away from the marketised interior, domestic interiors need to regain a central position in housing design. The interior must be considered a changeable and subjective process of multiple contributors that can develop over time and within different cultures as some of the design examples here have shown.

This research is funded by the Royal Danish Academy, Institute of Architecture and Design. The essay is based on an earlier article by Mette Johanne Hübschmann and Masashi Kajita.19

METTE JOHANNE HÜBSCHMANN is an architect and PhD candidate at the Royal Danish Academy. Her research reflects on domestic space and aims to qualify contemporary Danish housing and its interiors by addressing the gap between market-driven housing production and diverse human experiences.

HEADER: photo by Iona Marinescu

PUBLISHED: Maja 113 (summer 2023), with main topic Housing

1 As explained by Sally Stone in the podcast ‘A is for architecture’ episode ‘Interiority, Interior design and Change’ 23rd of January, 2023.

2 Wigley, Mark, ‘Untitled: The Housing of Gender’, in Sexuality & Space, ed. Beatriz Colomina (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1992).

3 Dolores Hayden coined the term ‘material feminists’ in her book The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities, published in 1982 by MIT Press.

4 Baydar, Gülsüm, ‘Wo/man in contemporary architectural discourse’, in Negotiating Domesticity: spatial productions of gender in modern architecture, eds. Heynen Hilde, Baydar Gülsüm (New York: Routledge, 2005).

5 Davidovici, Irina, ‘The Common Grounds of Housing’ ETH Zürich, April 5, 2022.

6 Roberts, Henry, ‘Model Houses for Four Families’, in The Dwellings of the Laboring Classes: Their Arrangement and Construction; with the Essentials of a Healthy Dwelling. Published by the Society for the Improvement of the Labouring Classes, London, 1867.

7 Evans, Robin, ‘Rookeries and Model Dwellings: English Housing Reform and the Moralities of Private Space.’ In Translations from Drawings to Buildings, (London: Janet Evans and Architectural Association Publications, 1997).

8 Fristrup Hus. 2020. Sales Brochure. By Carlsberg Byen P/S, available on their website. Downloaded March 29, 2022

9 Vedl-Petersen, Finn, ’God Bolig i Etagehusene’, [Good homes in multi-story housing], Statens Byggeforskningsinstitut, SBI-Anvisning 68, (Copenhagen: Teknisk Forlag, 1967).

10 Lütjens, Oliver, Unpublished Interview by Mette Johanne Hübschmann with Oliver Lütjens about the project Waldmeisterweg, 2022.

11 ‘Five Good Swiss Plans’, Online symposium organized by Kate Finning and Guillermo Fernandez-Abascal. Melbourne School of Design and the Embassy of Switzerland in Australia, 2022.

12 As described by Charles Holland in his article on e-flux ‘Still got love for the streets’.

13 Notably the beach house built for Nathaniel and Judith Lieb Beach House in Glen Cove, New York, USA, from 1969 by Robert Venturi & Denise Scott Brown.

14 London Housing Design Guide – Interim Edition. 2010. Mayor of London. Design for London August 2010. London: London Development Agency.

15 Mandrup, Dorte. ‘I Danmark er de almene boliger ikke almene. De er nedprioriterede boliger’ Politiken, June 18, 2018.

16 Forty, Adrian. ’The Comfort of Strangeness’, in 2G Sergison Bates, n.34, (Barcelona: GG Editorial Gustavo Gili, 2005).

17 Hyde, Rory. 2016. ‘The Return of Social Housing’, in Icon: Architecture and Design Culture. The Ends of the Earth, Issue 187. (London: Daren Newton, 2019).

18 Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), p. 34.

19 Hübschmann, Mette Johanne; Kajita, Masashi, ‘The Not-So-Open Open Plan—A feminist critique of the typical Danish interior’, in Interiors, 2023.