Improving the architectural quality of the existing housing stock requires integrating engineering solutions with architectural decisions. In the ongoing renovation marathon, it is important to discuss what kind of added value could be drawn from the existing to unleash the full spatial potential of renovation and to create good user-friendly spaces, writes Diana Drobot.

The aim of the current renovation marathon is to make housing stock dating from the last century (mainly from the Soviet period) more energy efficient. Buildings that came into use before the year 2000 make up 90% of the housing stock in Estonia;1 this includes 22,600 apartments with the total area of more than 28 million square metres.2 Currently, the goal is to renovate apartment buildings with 18 million square metres of living space to energy label C by 2050.3

Apartment building renovation projects, which are mainly made possible by support from KredEx, need to include the proposed architectural solution—i.e., standard-form principal design that specifies the interior finishes, connections, envelope, etc.—and a complete energy efficiency project. The supported architecture projects also need to embody the principles of the New European Bauhaus such as accessibility, affordability, climate goals and aesthetics, which need to be addressed in the design and access statement.4 The reconstruction ambition rests on one of the basic principles in the ‘Estonia 2035’ national development strategy, which aims for ‘a safe and high-quality living environment that takes into account the needs of all its inhabitants’.5 Thus, in addition to purely technical energy efficiency solutions, one of the main values in renovation should be henceforth the amplification of the architectural whole.

Rakvere at the finishing line of the marathon

In the lead of the renovation marathon is the town of Rakvere, which took off already in 2010. Renewal of the façades of standard Soviet-era apartment blocks in Rakvere began with the architecture competition for Seminari Street. The richness of the Seminari Street area comes from being in close proximity of both the city centre and a woodland. This street was the first to be renovated as it has the largest number of standard Soviet-era apartment buildings comprising of four types of buildings—so-called Tartu houses, Mustamäe-style 5-floor panel buildings prefabricated in the Tallinn housing construction plant, 3-floor silicate brick-built ‘khrushchevkas’, and 5-floor red honeycomb brick-built Masso-style buildings.6

In addition to ideas for restoring the residential buildings, entries to the 2010 competition were required to include a landscape architecture solution for the Seminari Street area that would create an inclusive (exterior) space and connect the centre of Rakvere with the urban forest in the southern part of the town. The first prize of this idea competition for turning Seminari Street into a linear park and renovating the façades of its apartment buildings was split between KARISMA Architects and the current b210 architecture office.7

The ambitious idea competition laid the groundwork in Rakvere for modernising its housing stock of the last century, and the characteristic public realm around it. By now, following the example of the Seminari Street, residential buildings have been renovated also in the city centre and Lilleküla district. Rakvere has also joined the LIFE IP BuildEST programme as a pilot municipality in order to contribute to working out the technical solutions for restoring residential buildings.8

As part of the project to make the building more energy efficient, Karisma architects re-designed the front elevation of a pre-fab apartment block to modernise it and to break its typical rhythmics. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

Today, renovation of post-war housing stock in Rakvere seems to continue in the tailwind of the initial inspiration. As for the works submitted to the 2010 competition, the façade of Seminari Street 1 was renovated based on the design ‘Elementaalne’ by KARISMA Architects. In addition to improving the building’s energy efficiency, the architects aimed to break the conventional rhythm of a pre-fab building. This is expressed in the façade graphics that have been designed asymmetrically with respect to the openings, and stairwell entrances with archetypical pitched roofs that were inspired by Rakvere’s wooden houses.9 The landscape solution commissioned from the authors of ‘Linna Metsa’ has so far not been realised.10

A conversation in 2016 between the city architect and the project designer of the renovation revealed that since the project was drawn specifically in response to the competition brief for Seminari Street, the city does not hold the rights to replicate the designs on other apartment buildings.11 In order to prevent future financial disagreements, the city organised a new competition, this time acquiring the rights to repeated use of the architectural solution.12 Subsequent renovation works have been inspired by the winner of the 2010 competition, i.e., Seminari Street 1 façade, in order to maintain coherence in the cityscape. According to the city architect, the green and grey colour scheme of the new solution refers to the natural environment. The brightness of the colouring is related to the building’s location in the town—the further away the renovated apartment building is from the centre, the more green there is in the façade solution. Following the current renovation trends, the side elevations feature oversized markings of the house number and/or name of the street.

Seminari Street in Rakvere is a good illustration of the fact that although residential buildings that have been renovated following a single style and standard might form a neighbourhood, it does not yet guarantee a coherent, supportive space between buildings. On the contrary—the public realm between these apartment blocks does not so much associate with the modernised buildings, but rather has a 20th-century vibe and brings to mind the desolate courtyards of my childhood, all the while disregarding the sensibility of Rakvere’s urban space that originates from its wooden houses and playful landscape around the castle.

Modernist heritage beneath the insulation layer

The paradox of renovating Estonia’s modernist heritage is that by dreaming of moving away from the historical connotations of East Europan (post-)modernist mass housing production and the image of monolithic neighbourhoods, we risk losing the value of this heritage altogether. In reusing our Soviet-era architectural heritage, we should keep in mind that Estonia’s socialist residential architecture also bears the hallmarks of Scandinavian mass housing production, which is highly appreciated today. Renovation and reconstruction should take into account both the formal and material side of the buildings, as well as the ideas and values reflected in the architecture.13

Analysing our modernist apartment buildings, we can note that one of the aims of amplifying the architectural whole would be to highlight the existing heritage. The rhythms, recurrences on the façades and volumetric articulation that is characteristic of modernist mass housing tend to get lost when the buildings are updated, thus making the historical decor fall into neglect. In Estonian architecture, designing of local mass-customisable residential buildings was advanced by architect Miia Masso. Distinctive Masso-style apartment buildings reflected the values of modernist architecture in their combination of façade materials and decor—articulation on the façades, expanded potential of bricks as a playful material, signature colour duets on openings. Masso-style buildings have been preserved in their original form in Tallinn, and are still somewhat recognisable in the neighbourhood around Allika Street in Keila, but have been buried under modern insulation at Seminari 11 and 23 in Rakvere.

Modernist features have been emphasised well in the building at Pikk 8 in Pärnu. Instead of reducing façade elements, the aim has been to add missing historical value, all the while taking into account the surrounding buildings. Successful and aesthetic reconstruction was also facilitated by the fact that the area is under heritage protection.

(City) architect as a key link in the renovation process

The position of city architect involves an opportunity to put together architecture competition briefs that are more broadly considerate of the local urban space. And yet, it looks like city administrations are not issuing design provisions, and in case of renovation, the role of the city architect is limited to confirming the detail plan and draft. Furthermore, commissioned drafts often conform only to the designer’s vision or creative and aesthetic choices (colouring, finishing materials, geometry and graphics on the façades, etc.). At the same time, the focus of renovation is simply on updating the technical performance and envelope of the building—the façades have a polished, new-like look—but the environment in which the building should form an integrated whole with the surrounding streets, public space and other adjacent buildings, is left undetermined.

It is important to enable creation of new space and heritage in the course of renovating, delicately integrating it with what already exists. The mentality of adding architectural value has already resonated in the Estonian architecture scene. Architectural practice PART, led by Sille Pihlak and Siim Tuksam, is looking for ways to integrate a new type of mass-customisable construction system with last-century modular houses—i.e., panel buildings—and join them into comprehensive functioning neighbourhoods.14

Examples from Europe

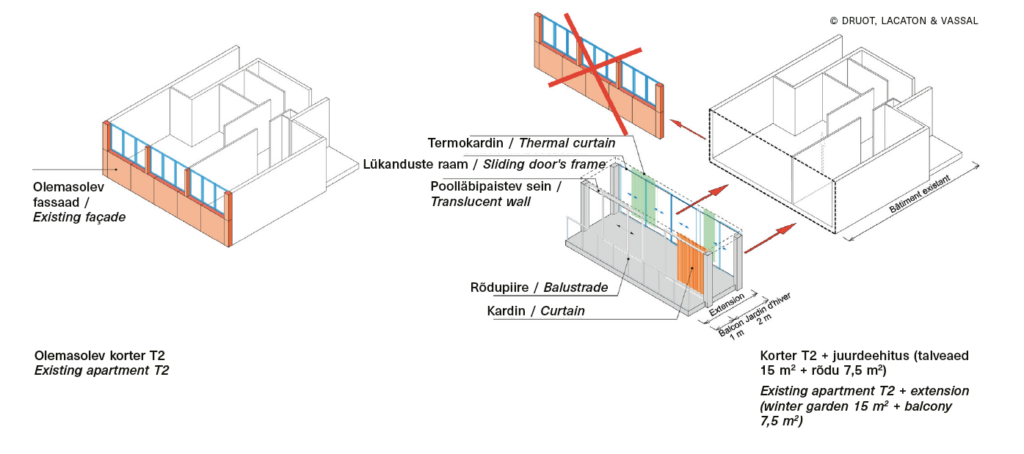

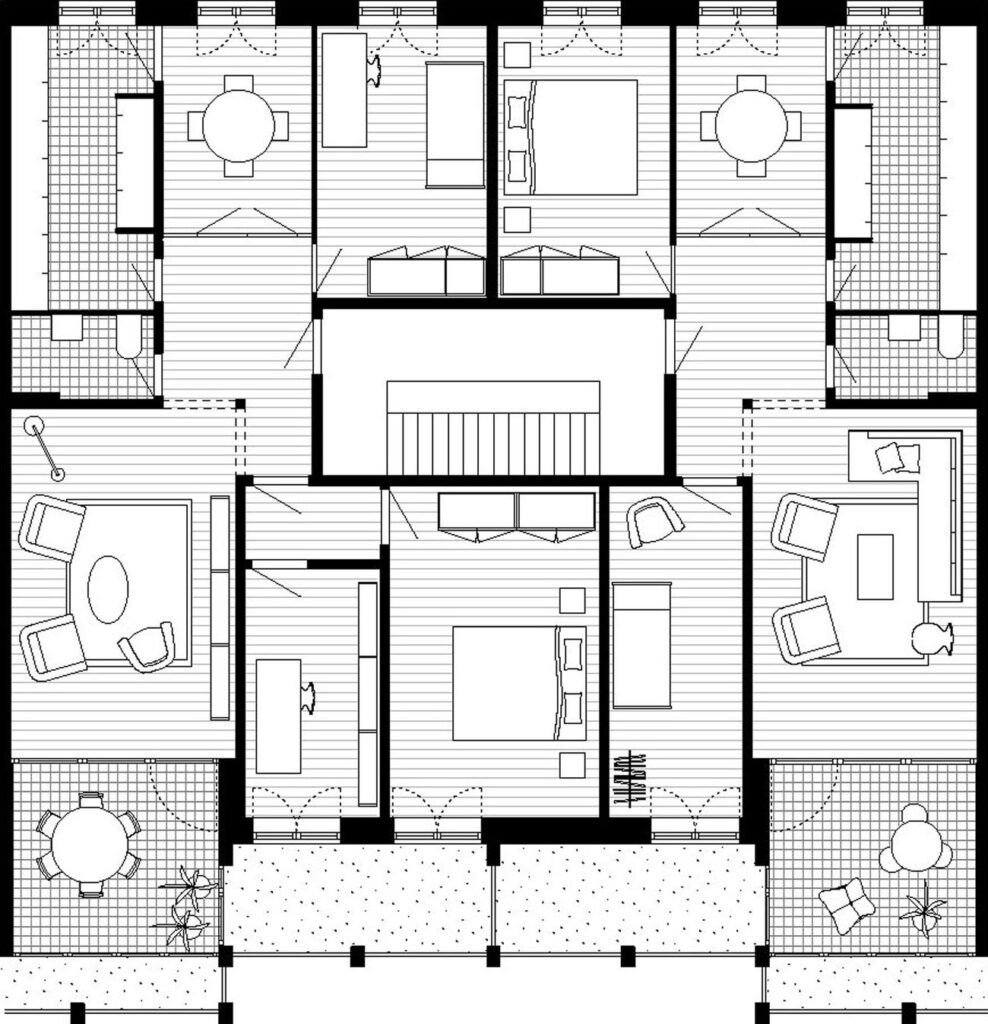

It is also worth to look at successful renovation projects of mass housing in Europe, focussing on two different scales—building- and area-based renovation. Building-based renovation is exemplified by Bois-le-Prêtre in Paris, a collaboration between two architecture offices, Druot and Lacaton & Vassal (2008–2011). The building was originally designed by Raymond Lopez and Eugène Beaudouin in 1961. The renovation design was repeatedly modified—e.g., by increasing the number of apartments and size of useable area, as well as by replacing façade elements with winter gardens and balconies that extend the apartments. The volume of the building grew from its original 8900 m2 by over a third (i.e., by 3560 m2).15

Area-based renovation is illustrated by architect Adam Khan’s project Ellebo Garden Room (2013–2020) in Copenhagen. Besides renovating 260 social apartments, the project also revised the volumes of the buildings—semi-public spaces were added to the roofs, and the courtyard was vivified by modernising the inner façades, successfully turning it into an inclusive and user-friendly public space.16 Yet, the romanticised block-based renovation was ultimately not complete—only two of the original four buildings that had surrounded the courtyard have survived; the barren plot between them where the other two used to stand has now been replaced with car parks. Enclosed courtyards are characteristic of socialist architecture, which is why this example of filling a semi-public outdoor space with user-friendly functions is relevant to the Estonian context.

The opportunity to amplify the architectural whole brings to the fore the importance of the architect in renovation. By proposing a clear concept for the renovation of an urban district or individual building, the city architect can ensure the creation of a comprehensively functioning environment. Lucid competition briefs enable to retain the value of urban space while renovating or even add to it. A comprehensive approach to renovation involves creating comprehensive (micro)districts and active spaces between the buildings, where the missing value—the architectural potential of the building—has been realised. Efficient renovation process requires active and transparent cooperation of different parties. This means that in addition to those with technical skills, the creative process should also involve apartment associations (representing the interests of permanent residents). The renovation process is improved by enabling the residents to have a say in colour solutions, choice of materials, and possible variations. Limiting the intervention (adding of balconies or changing their potential dimensions) as well as extending the potential uses of a façade and the general concept of a home promotes the creation of a varied and multifunctional area.

In carrying out a pragmatic, efficient renovation strategy, it is worth to take it slow and pay attention to the aesthetic and architectural integrity of the result, acknowledging that architecture should not finish last in the renovation marathon.

DIANA DROBOT is a Master student of architecture at the Estonian Academy of Arts (EAA). She also conducts creative research into mass-customisable and volumetric building envelopes at EAA’s Timber Architecture Research Centre PAKK.

PÄÄR-JOONAP KEEDUS is an architecture photographer and a Master student of interior architecture at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

HEADER photo: Päär-Joonap Keedus

PUBLISHED: Maja 113 (summer 2023), with main topic Housing

1 Carpenter, Griffin. ‘Cold truths about our cold homes.’ New Economics Foundation, February 8, 2018.

2 Hoonete rekonstrueerimise pikaajaline strateegia. Tallinna Tehnikaülikooli Ehituse ja Arhitektuuri Instituut & Majandus- ja Kommunikatsiooniministeerium. Tallinn, 2020.

3 Arumägi, Endrik, et al. Hoonete kuluoptimaalse energiatõhususe miinimumtasemete analüüs. Tallinna tehnikaülikool, 2017.

4 ‘Rekonstrueerimistoetus 2022-2027. Nõuded rekonstrueerimisprojektile.’ KredEx.

5 ‘Estonia 2035.’ The document can be found from the Government’s websitel.

6 Paadam, Katrin, et al. Integreeritud linnalise arengu kontseptsioon Rakvere Seminari tänava piirkonna näitel. Tallinn & Rakvere: Baltic Union of Cooperative Housing Associations, 2011.

7 ‘Rakvere Seminari tänava piirkonna ümberkujundamise ideevõistlus.’ Eesti Arhitektide Liit. http://www.arhliit.ee/uudised/seminari-ideevoistlus/.

8 ‘Rakvere liitus projektiga LIFE IP BuildEST.’ Rakvere Linnavalitsus. https://rakvere.ee/kaimasolevad-suurprojektid/-/asset_publisher/0897l7VwD5SZ/content/rakvere-liitus-projektiga-life-ip-buildest.

9 ‘Seminari korterelamu fassaadid.’ KARISMA Architects. https://karisma.ee/project/seminari-kortermaja-fassaadid/.

10 In conversation with an author of the winning entry ‘Linna Metsa’.

11 Tuleviku 6, Rakvere energiatõhusaks rekonstrueerimine, EHR

12 Rudi, Hanneli. ‘Rakvere on kortermajade renoveerimises Baltikumis esirinnas.’ ERR, March 17, 2023. https://www.err.ee/1608918935/rakvere-on-kortermajade-renoveerimises-baltikumis-esirinnas.

13 Ojari, Triin. ‘Nõukogude arhitektuuri uuskasutuskeskus.’ LP, September 9, 2013.

14 Karro-Kalberg, Merle, Sille Pihlak, and Siim Tuksam. ‘Renoveerimismaratoni esimene kilomeeter.’ Sirp, January 20, 2023.

15 Ayers, Andrew. ‘Lacaton & Vassal’s revitalisation of a Parisian tower block.’ The Architectural Review, December 22, 2011.

16 ‘Ellebo Garden Room.’ Adam Khan Architects. https://adamkhan.co.uk/projects/ellebo-garden-room/.