Location: Vilnius, Lithuania

Architecture: Studio Peteraitis (Mantas Peteraitis)

Client: A group of 16 individuals

Size: 887 m2 (prior to conversion), ca 1185 m2 (post-conversion)

Cost: €930 000

Year: 2017

In Vilnius, a group of friends came together to acquire the top floor of a Soviet-era factory building. They later cooperatively developed it into their homes. Laura Linsi talks to Mantas Peteraitis about how the project came to be.

Please tell us a little bit about the background of the project. How did it start? Why in this location?

The project started in 2004. We were travelling with a group of friends, mostly young architects, to a resort in Crimea for a holiday. At the time, the train connection between Riga and Simferopol still existed. A friend informed us that an old and dilapidated Soviet-era factory building in Vilnius was at that time under offer from a company that had recently gone into administration.

We discussed the opportunity to participate in the auction and buy a whole floor of the building, in total about 1,000 m². We were successful, and thus, we acquired 1,000 square meters in a huge factory complex built in Soviet Lithuania in the 1960s. The building didn’t even have an address, but only a code name ‘555’, having been part of a secret factory. The factory had produced electronics for the military as well as civil use.

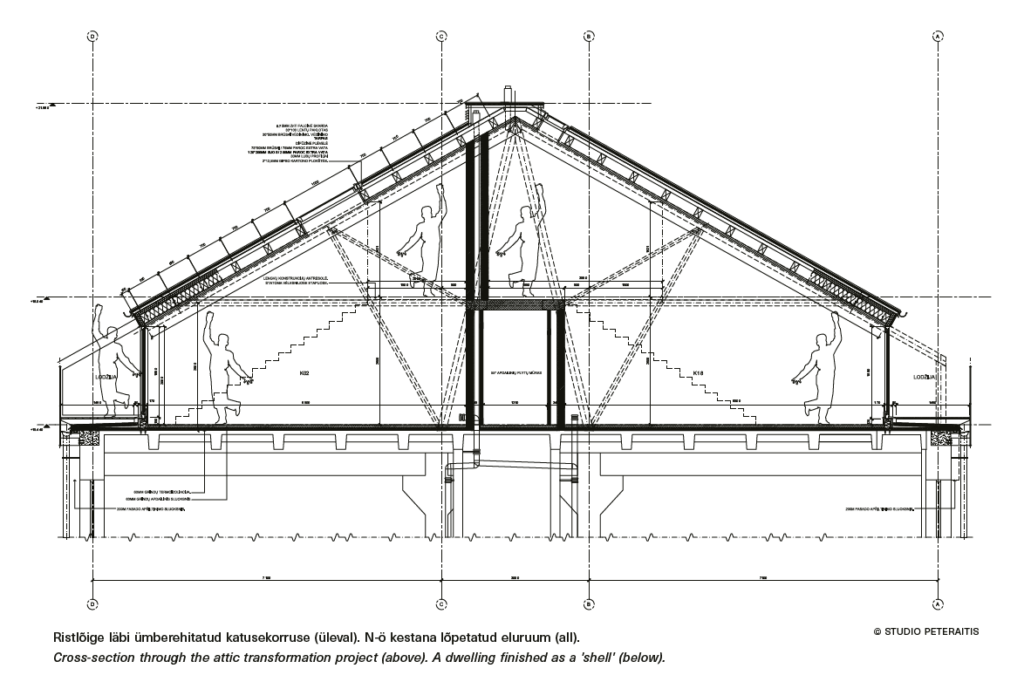

It took about five years to make the space liveable. At the time, we inhabited the top, i.e. 3rd floor of the building, the attic space remained unused. We had to install a new substation, drainage system, water supply and other necessary basic infrastructure. The interior space of the building was stripped down to a bare shell and divided into compartments, which people could then move into. However, despite substantial communal effort, the building and its surroundings were still in need of much more improvement. The roof above the empty attic floor, for example, was leaking and in a serious state of disrepair. More extensive action than our occasional patching of it was needed to make it leak-proof and reliable.

Did you legally form a cooperative to further develop your shared property? Was there immediately a common understanding within the group about what to do and how to do it?

The roof is normally the most expensive part of any building structure, and so the idea to convert the attic space into apartments in order to make it useful was naturally floating around. The idea was that the new units would cover the cost of a new roof. I offered to take on the role of the architect in the conversion and ended up developing several design proposals. I was living in London at the time and saw the Vilnius project as an experiment—a community project distinct from commercial undertakings with tight deadlines that were typical to my job in London.

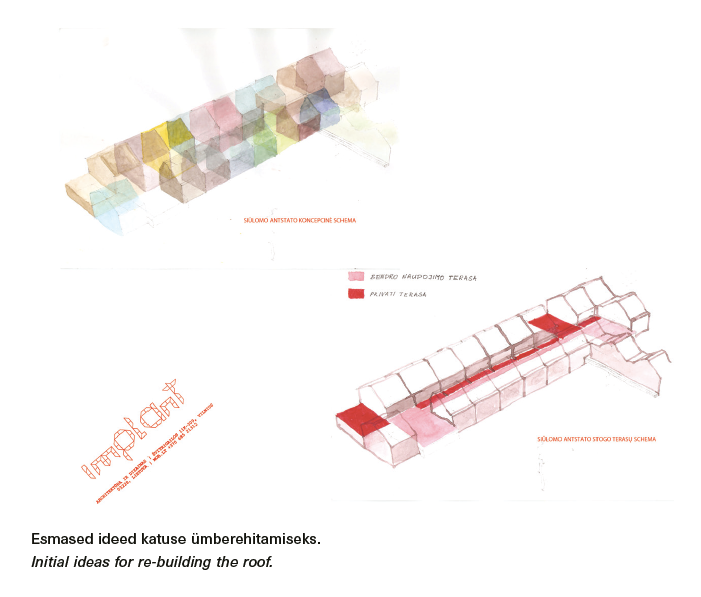

My first proposal was to look at the roof space as a plot of land. I drew an imagined masterplan which divided it into 16 individual plots. There were 16 people in the group and my idea was that each of them would commission a separate architect to develop their individual segment. The roof would become a mosaic—a row of terraced houses with a central, elevated communal street or alleyway. I presented this project to the municipality, but, to my disappointment, the planners argued that a proposal of this nature is not feasible due to various legal reasons. I was advised that from a planning point of view, it would be much easier to keep the existing contour of the pitched roof.

As per the advice, my next step was to slightly modify the arrangement of the attic layout by removing the parapet and opening up the perimeter to the outside, as well as allowing for some roof lights. We were granted the outline planning consent in 2014. I moved back from London to Vilnius and worked on the technical stages of the project. We received some quotes from builders and soon realised that the amount of money required for the project was way too much for everyone’s pockets. At that point, we as a group signed a legally-binding commitment agreement to avoid a situation in which the project halts due to some individuals lacking funds.

We then had to approach the banks. However, the banks wouldn’t give us a loan because lending to a group of individuals was outside their usual practice and didn’t pass their risk assessment. As a result, some members of our informal cooperative panicked and sold their parts off. Luckily, the new people who came in had the capacity to move on with the project.

It sounds like everyone took on quite a risk.

That’s correct, but when buying on the market is not an option, you have to take risks. But also—when you do something for the first time, you do not know what awaits. And then there is no way back.

Is the property still owned by the co-operative now?

The property was divided into 16 privately-owned units. The people who participated in building the extension became members of the apartment association, as is the standard practice in case of multi-story dwellings.

What were the main obstacles to and challenges of carrying out the project?

The building process was not as smooth as we would have liked due to the lack of financial flexibility. I acted not only as an architect but also as a project manager—I had to run the whole thing as well as deal with 15 people who were my clients. Furthermore, I was providing design services while being a client and shareholder myself. Having insider knowledge of the non-existent budget flexibility put a lot of strain on the process.

In most cases, our group acted very positively. However, there were a few cases when someone would not cooperate. The initial design principle was to keep all the spaces as similar to each other as possible to avoid disagreements and make sure that the funding of each single unit is proportional to other units. But even the simplest scheme would involve some differences between separate spaces. Some units would be facing south, others would be facing north, and so on. This caused tensions between the group members.

The biggest challenge, however, occurred in the period when the earlier roof had been removed and a new one was still to be constructed. Water penetrated the temporary roof protection and reached the inhabited spaces below ours. This caused a huge division between the parties. Unfortunately, a lot of the blame fell on the self-appointed architect and project manager.

Ultimately, the project was completed with all units as ‘shells’ that the inhabitants could lay out themselves. To what extent did they? Is it just differences in decoration, or also in the number and layout of rooms, or even stories?

The Lithuanian building code requires a certain minimum amount of work to be finished, i.e. electricity, heating, plumbing, basic surfaces, in order to give the building a use permit. The owners of the units had to commit to complete these minimum works. After this, a lot of units proceeded with the internal finishing works in an organised manner just because it was obviously much more cost-effective to do it in bulk. For example, we bought a large amount of white spruce floorboards from Latvia—this kind of boards would be impossible to purchase in small amounts. Also, we wanted to have a terrazzo floor throughout the lower floor of the attic. The contractor advised us that it would be impossible to pump up the large-particle aggregate to the height of 18 meters above ground, so I developed a specific type of terrazzo to suit the specification of the machinery.

Is there anything you would like to emphasise in relation to the quality of architecture in this project that would be unlikely to appear in a speculative development project?

Absolutely. In Lithuania, a project brief for a commercial, speculative development would only allow the architect to follow a very narrow path of design decisions from the very first days of engagement. Some developers have even prepared packages of detail and material specifications, which are included in the brief prior to commencing the design process.

You mentioned to me once that in your view, this way of building dwellings is the way for the future. How come?

Despite the many obstacles, I am very happy that we went through what is, at least in our country, an unprecedented experiment. To my knowledge, this was and still is the only communal effort to build in such scale and complexity in Vilnius.

In the past 30 years, Lithuania has seen a boom in residential construction. However, it does not look like a lot of noteworthy architectural quality has been created. The reason for this is systemic—the private sector looks for a quick return and the public sector seeks the lowest price. In such circumstances, there is no real interest in creating sustainable and long-lasting designs.

In contrast, the cooperative way of building involves stakeholders who are from the very start of the process directly interested in quality, longevity, and other aspects necessary for good design. As I mentioned, the downside of such a process, at least in Lithuania, is the lack of funding mechanisms. Countries like the Netherlands, Switzerland or Austria have long cooperative building traditions and have developed ways to finance these processes. They should be taken as examples. I truly believe that a considerable part of housing in our cities should be provided in such a way. It would raise not only architectural quality, but the overall quality of human life as well. After a few years of going through a learning curve, we have become a wonderful neighbourhood.

MANTAS PETERAITIS is an architect with a focus on environments and structures that are socially, aesthetically, and technically sustainable.

HEADER photo: Tautvydas Rasiulis

PUBLISHED: Maja 113 (summer 2023), with main topic Housing