On the site of the former ETKVL vehicle depot in the area between Tulbi and Veeriku Streets in Tartu, nine 2–5-storey apartment buildings with a total of 176 flats designed by Indrek Allmann and Katrin Koit of Pluss Architects were completed in 2006–2007. The modern architecture map of Tartu describes the residential area as follows: ‘Tulbi-Veeriku Residential District is the first comprehensively planned and constructed contemporary residential area without fence enclosures in Tartu (and probably in Estonia). In addition to buildings, also the varied landscape and green areas provided for in the winning entry of the planning competition were constructed to create the friendliest living environment in the whole city.’1 The author of the acclaimed landscaping is Kerli Sirk (AS K & H). The outdoor area is positioned between the buildings in such a way as to form an integrated whole that may not be immediately apparent to passers-by, much like the underbelly of a hedgehog.

In the video clip by Maja in 2006, the architects explain that the aim was to break the monotony and create a safe and private residential district.2 For the given purpose, traffic is led to the outer perimeter, there are no vehicles between the houses so that children could freely run around the yard. The space between the buildings takes the primary role, with an artificial landscape replacing the former tarmac field. The soil excavated during the construction was used for the so-called Teletubbyland that now articulate the yard area into separate private spaces. The outdoor area is divided into a public yard open for everyone, a semi-private area of roof terraces jointly owned by the residents (can be booked by the residents in the given staircase) and the usual private terraces and balconies accessed from the apartments.

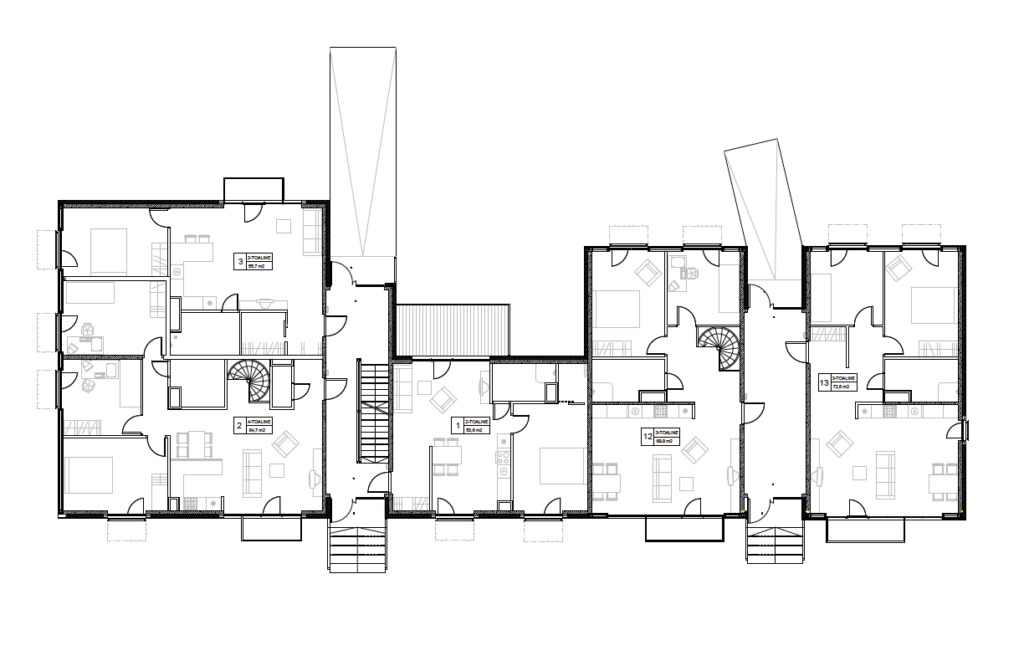

The buildings stand out for their spacious staircases with two entrances opening towards both the main elevation (that is, the parking lot) and the courtyard area. According to Indrek Allmann, the fact that there is no basement parking allowed the architects more freedom with the plans, in other words, the structure, including the location of load-bearing walls and thus also the floor plans, is not determined by the traditional spacing of the parking lot columns. The owners were given the option to choose the location of their balcony. Allmann also highlights the then experimental timber frame external walls alongside the concrete load-bearing structure. There are only 2–3 flats on each floor of the core, not quite matching the standard economic models of the developers. However, privacy sells and makes the project stand out, so that is the price of a good project. It seems that the gamble paid off—at the height of the property boom, almost all flats were sold already in the planning stage, with no advertising and at a higher-than-average market price. The building at 12D Veeriku was given the prize of the best apartment building in Tartu in 2007.

Among other things, the architects point out in the film that Tulbi-Veeriku district is an excellent example of how good planning is the basis for a good living environment. The masterplan forming the basis for the project3 was adopted in 2005, the authors were young specialists Heiki Kalberg (currently in Artes Terrae) and Karin Bachmann (currently in Kino Maastikuarhitektid) who have now clearly established themselves as capable and innovative landscape architects standing for the importance of public space. It is worth noting that the planning of the residential district was based on the winning entry of the architecture competition. Any planning competition, even if it is not a public but invited competition, helps to reduce later conflicts between the strict regulatory legal act, that is, the framework set by the plan and the more detailed creative work, that is, the architectural project. As a rare exception in planning, the masterplan of Tulbi-Veeriku residential district specifies the mandatory minimum surface area for the roof terraces—13–21% of the roof’s surface area must be a walkable terrace that has become a semi-private shared space above the ground. The water tower in the vicinity subject to planning had to be preserved with the possibility of extensions (starting from the wider top section), e.g., balconies, stairs, lift, windows etc. The landmark has still not been completed and the application for design specifications from 2022 is still being proceeded.

Ingmar Pastak, a human geographer researching among other things the topics of identity, affiliation and spatial inequality wrote a study at Tartu University on Tulbi-Veeriku district in 2013. He considers it an important flagship project allowing to experiment with innovative planning in the urban landscape.

Pastak estimates that Tulbi-Veeriku district primarily accommodates middle-class residents with few very rich or very poor people. Interviews with the residents revealed that there was relatively little communication taking place between them: ‘It is partly because the flats are set in a way that you physically do not see or hear your neighbours. In the case of a new residential quarter, there are fewer daily issues that require interaction between the residents to solve problems and improve the living conditions than in the apartment association in older buildings.’4 The interviews also revealed that the roof terraces had practically no use. The public yard mainly functions as a children’s playground, the residents do not use it and there are no facilities for spending time there: ‘Single park benches do not really carry this role’.5 Pastak assumes that since the district is quite homogeneous in terms of age, you do not see any elderly people sitting on the benches or other kind of social life in the yard area. Based on his observations, Pastak claims that the green outdoor area between the buildings is used considerably less than the yards and gardens of the nearby private houses or even older apartment buildings, in other words, although the recreational area exists, it is clearly underused.6

Pastak sums the development up as follows: it is a desirable living environment due to good architecture and landscaping, high-quality construction and planning that minimises contact with neighbours. The last remark is curiously at odds with the common outdoor area and semi-private roof terraces, that is, the concept of spaces encouraging communication, but perhaps this is the key: residents must have the opportunity to hide from their neighbour’s prying eye and also come together when they feel like it. In his estimation, however, there had been no dialogue between the developer and the future residents: ‘The residential district seems to be a product manufactured without negotiating with the consumers. It appears that market segments were analysed and a high-quality residential area was generated. At the same time, the development process did not involve local and future residents.’7 Thirdly, Pastak makes a highly critical remark that the public space does not serve the original aim: ‘It may be said that the planned public leisure area has been realised as one large sandbox. The courtyard only conveys a strong visual impression. It is like a buffer zone, a separator rather than a public space to bring people together. [—] Thus, Tulbi-Veeriku development does not aim at providing an environment-friendly and sustainable living environment, it is a business venture driven by profit.’8

The research suggests ways to better integrate public space and the courtyard to provide the residents with better opportunities for leisure. For this purpose, Pastak suggests, an apartment association meeting could be held for outlining a future vision and the necessary steps to be taken, new seating and covered barbecue areas could be established, similarly bike racks, a traffic park for children etc. Secondly, he would increase interaction between the residents and boost the local identity and social networks as the developer has indeed built the physical space but neglected the so-called soft development (creating a common sense of belonging and the image) that is needed for ensuring security, quality of life, singularity and social networks in the area. None of these remarks are anything special in the light of contemporary knowledge and practices, but rather elementary and mandatory design elements for the areas between buildings where Jan Gehl’s fruitful and tireless public space propaganda has successfully borne fruit in Estonia.

Curiously enough, Pastak’s research shows that the nearby residents would like to take their children to play in the courtyard but shy away due to a prohibition sign. Also, an article in the daily Päevaleht in 2008 mentioned the intimidating ‘Private area’ sign ‘punched in the ground in the middle of the most attractive playground’.9 The complex has been compared to an atoll with a recreational area in the middle safely protected from the outside world. Like a pearl kept just for yourself. To the credit of the residents (?), the sign is nowhere to be seen in 2023.

Nevertheless, it is worth highlighting the spacious and light staircases affording views through the building and connecting the more private and public spaces, accesses to flats and the courtyard area. Although 17 years later, it may seem strange that such a solution was so highly valued, at the time it featured outstandingly high quality and distinctive features, and it is true that the volume and façades of the buildings are well articulated with the combination of materials adding to their charm. After the extensive postmodern tinkering with metal cladding, plastic and other materials in 1990s, the use of timber in early 2000s is indeed more revolutionary, so what if nowadays you cannot even get a quality label for your project without it.

Today, both architects and landscape architects-planners would probably do some things differently. There is no space for bicycles and this is visible everywhere: with no bike racks, people utilise lamp posts, bin shed walls and corridors, a catalogue bike shelter has now been installed in one corner of the plot. Obviously, there should be more bike shelters, especially covered ones, in such a residential quarter aiming at keeping motor-vehicles at bay. The nondescript turnpike barriers strip the living environment of some of its charm—in more recent plans, there are ways to ban such solutions and enclosures. Pushing cars to the edges to make the courtyard cosier comes at a cost: the parking lots are huge and sometimes adjacent to identical ones next door, there are few trees and so the area comes across as a hedgehog—from the outside you see spines and intimidating tarmac fields, inside there is a cosy and inviting courtyard, thus making the hard and soft spaces collide. With its mainly trimmed lawns, the outdoor area clearly lacks biodiversity by today’s standards, however, there are also flowering patches in some of the edges. Trees, bushes and balcony gardens could all be much lusher and more versatile. In recent high-quality and award-winning landscape architecture projects we have started to see covered common spaces between buildings (e.g., Öö quarter in Tartu, Veerenni neighbourhood in Tallinn), either greenhouses, barbecue areas or mixed-use spaces sheltering from wind and rain.

In any case, Tulbi-Veeriku residential quarter as a leading example of its era illustrates the fact that local governments had already by then grown stronger and the use of architecture competitions had become a standard part of urban planning in Tartu. After nondescript real estate villages, developers had acknowledged that economic success is ensured by distinctiveness and high quality, architects had become aware of the equal role of the spaces between buildings and landscape architects had begun their quest to make themselves heard and seen. Naturally, many things could have been done better, however, this, I think, should be taken as a compliment to all stakeholders in the process of spatial design, as it would be quite sad if a complex built in 2007 remained the highpoint of the century and an insurmountable peak.

ELO KIIVET is an architect, urban planner and placemaking enthusiast. Currently, she is the Deputy Mayor of Tartu.

HEADER photo: Arne Maasik, Museum of Estonian Architecture

PUBLISHED: Maja 113 (summer 2023), with main topic Housing

1 The map is available on Google Maps app by entering the keyword ‘Modern Architecture in Tartu’.

2 The video clip from the series of architecture programmes ‘Maja’ was published on YouTube by the Estonian Centre for Architecture in 2009 titled ‘Estonian Contemporary Architecture: Tulbi-Veeriku Residential Quarter, Tartu’.

3 The detail plan is available on the plan website of the city of Tartu (plan DP-04-106).

4 Ingmar Pastak, Tulbi-Veeriku elamukvartal, (research, Faculty of Science and Technology of Tartu University, 2013), 10.

5 Ingmar Pastak, Tulbi-Veeriku elamukvartal, (research, Faculty of Science and Technology of Tartu University, 2013), 11.

6 Ingmar Pastak, Tulbi-Veeriku elamukvartal, (research, Faculty of Science and Technology of Tartu University, 2013).

7 Ingmar Pastak, Tulbi-Veeriku elamukvartal, (research, Faculty of Science and Technology of Tartu University, 2013), 15.

8 Ingmar Pastak, Tulbi-Veeriku elamukvartal, (research, Faculty of Science and Technology of Tartu University, 2013), 15.

9 Arvo Uustalu, ‘Tartu Veeriku atollmajadel on mägine koduhoov’, Eesti Päevaleht, 26.01.2008.