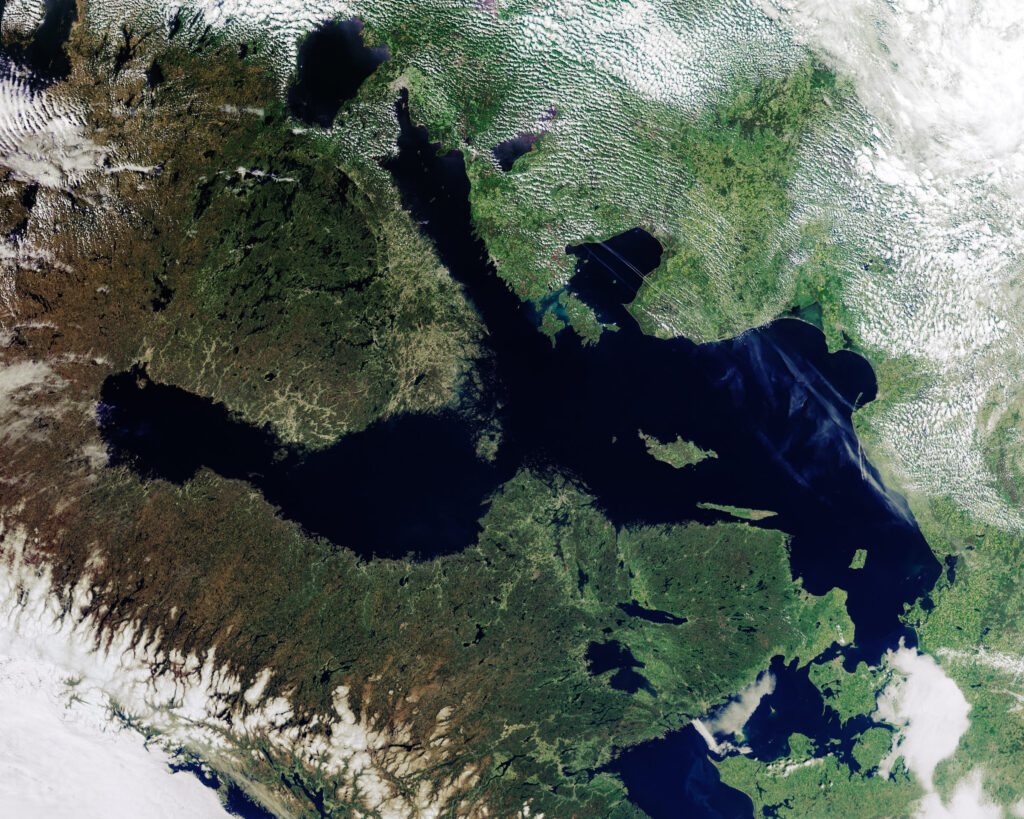

More than 85 million people live in the extensive catchment area of the Baltic Sea. Historically, the Baltic Sea has been an important economic, political and cultural resource for the coastal peoples while also shaping their self-awareness and landscape, including cultural landscape. However, human connection to environment is waning. One of the ways to alleviate environmental problems might lie in architecture that brings people closer to their environment again. Estonia as a maritime nation has plenty of opportunities for this.

The changing meaning of landscape

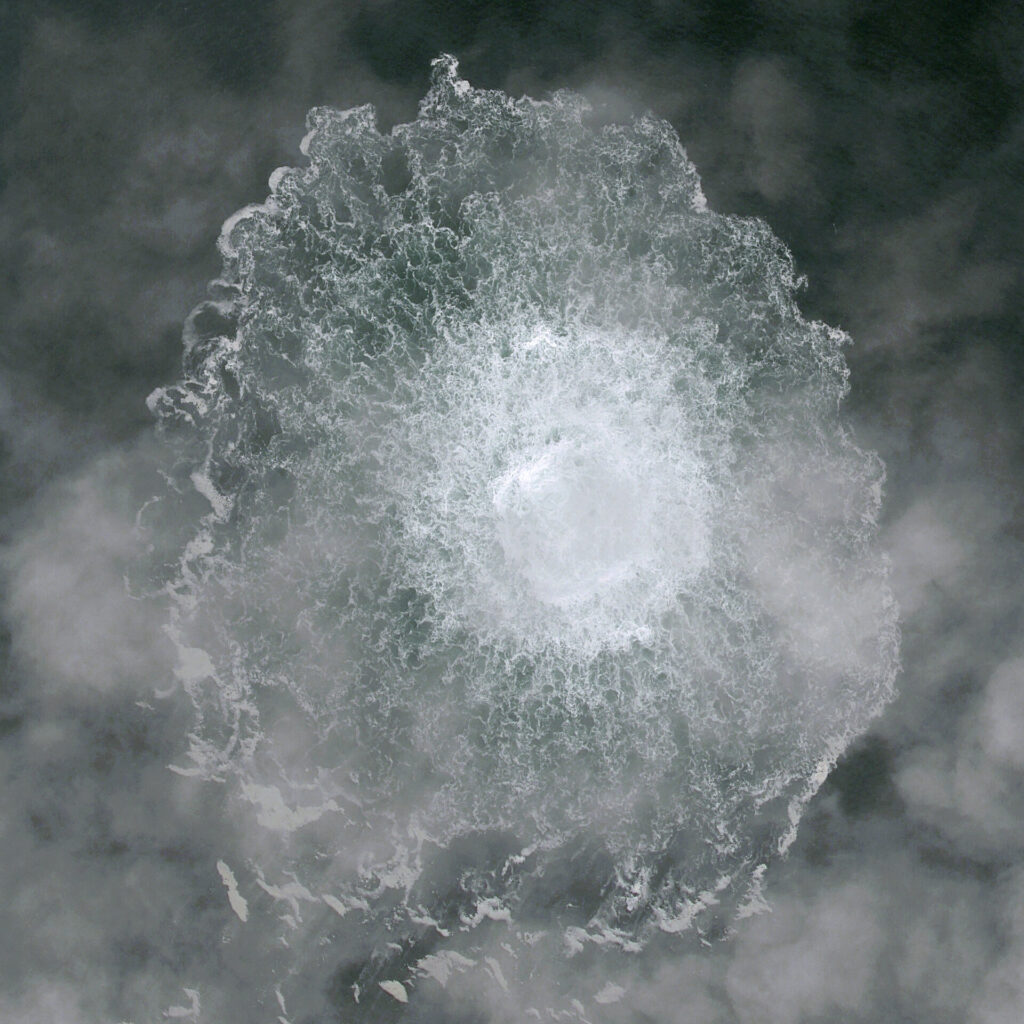

Before the Industrial Revolution, people had personal and dependent relations with nature which explains their need to describe their surroundings and define themselves through landscape. For coastal peoples, the sea has played such an important role in their daily lives that, for instance, the Estonian Swedes living here on the coast and islands called themselves aibofolke, that is, island people.1 However, people alienated from their environment attempt to control nature without actually understanding it. Due to the impact of entertainment, tourism and new technologies, the Baltic Sea has become one of the busiest seas in the world dominated by phenomena related predominantly with economic interests such as mazes of shipping lanes, infrastructure and shipwrecks.2 As a result of human activity, the Baltic Sea is suffering tremendously from various environmental issues, occasionally reminding us that no agreed boundary merely drawn on the map stops the spread of ecological problems.

In the context of the climate crisis, we need a new approach to landscapes that would not oppose man to nature but would strive for a balanced whole. Landscape architect Christophe Girot has said that rethinking the relationship between man and nature could alleviate our current uncertainty about it. Instead of rushing to save it, nature should become an integral part of the contemporary city. According to Girot, the solution could lie in what he calls an ‘immanent landscape’. In Girot’s approach, immanence, which stands for the characteristic and intrinsic features of an object or phenomenon, describes a landscape that interweaves knowledge from various fields such as (landscape) architecture, engineering and urban planning.3 In the following, I will attempt to provide an overview of an immanent landscape based on the features of the sea as a physical as well as an imaginary space.

The Baltic Sea as common space

The term ‘commons’ originates from medieval Europe standing for land in common use. Over time, the meaning of the word has expanded to all sorts of common resources, including cultural assets (for instance, information) as well as natural landscapes (forests, bodies of water).4 In order to discuss the spatiality of the seascape and the accompanying multi-layeredness, I will expand the term to ‘common space’. The Baltic Sea is common space that connects the states and people living around it and over the centuries has played an important economic, social and cultural role in their lives. On the one hand, the sea is the connector between the people living around it, illustrated, for instance, by the commercial and political Hanseatic League operating from the 13th to 17th century. On the other hand, it has also acted as a divider both during the Soviet era and the centuries of the pirates’ reign of terror.

The large freshwater inflow into the Baltic Sea and poor connection with the ocean lead to the low salinity of the seawater making the ecosystem of the Baltic Sea unique and vulnerable.5 In order to prevent the harmful effects of human activity, we need to significantly decrease human presence in marine waters and cooperate in planning maritime areas across state borders. The Estonian Maritime Spatial Plan adopted in 2022 could be of interest to architects and planners for several reasons. First of all, it emphasises that due to strong connections between sea and land, it is important to consider their planning together. Thus, the plan provides guidelines for local authorities’ planning departments on spatial contact points between the sea and the land (such as ports, cable connections). Secondly, the plan provides an overview of the valuable coastal landscapes (such as Neugrund Shoal) and precious cultural heritage (such as areas with numerous shipwrecks). The spatial impact of the guidelines clearly extends to land.6

International cooperation to improve the ecological situation of the Baltic Sea has been conducted for decades. In 1974, the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission HELCOM was established together with conclusion of Helsinki Convention which was renewed in 1992 between the countries surrounding the Baltic Sea (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Poland, Germany and Russia) and the European Union. The aim of the convention is to protect the Baltic Sea from loss of biodiversity and sources of pollution and to promote the sustainable use of marine resources.7 Since 2010, HELCOM has been working on the spatial planning of the Baltic Sea region to achieve a spatial coherence in the area.

However, besides planning, it is also important to implement projects and spatial solutions on a smaller scale. Although the sea is our collective asset, public interest in managing it is relatively low compared to land. It may be due to the fact that many relevant decisions related to the sea are made behind closed doors and most people do not have a close everyday relationship to it.8 One way to improve environmental awareness is to make sea-related topics visible in the public space. Architecture could inspire and help people to make connections and embrace changes.

Seascape — a diverse frontier with healing properties

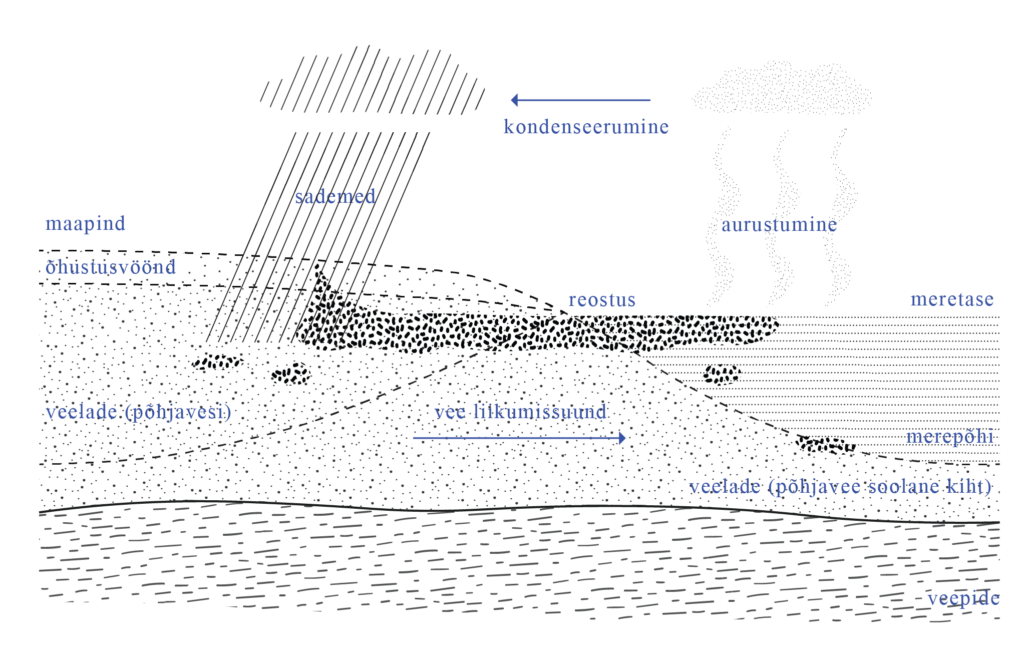

Seascapes, including the coast, help to describe the sometimes hidden connections in landscapes. They are characterised by constant mobility and volatility. The Italian word tempo, meaning both weather and time, points to the link between the passage of time and the change of landscape.9 Changes resulting from weather conditions that people have used in tracking the passage of time over centuries are particularly evident on the coast. Variability gives rise to the biological diversity in coastal areas and allows to predict natural processes related to climate change.10 This is also where the geological relation between the land and the sea comes to the fore: the spread of pollution between two seemingly separate spaces is proof that despite the borders, there is a continuous cycle of matter in landscapes, with water playing a crucial role. Designed by architect Álvaro Siza, the Leça pools in Portugal effectively illustrate water’s ability to create changing spaces with tidal movements by simultaneously shaping and being the space.

No agreed boundary merely drawn on the map stops in spread of ecological problems.

In her book Atmosphere Anatomies, Silvia Benedito points out that contemporary architecture tends to approach landscapes from an observational perspective, that is, focusing only on what could be perceived through the eyes. Since people’s spatial experience is influenced by the atmosphere around them which is fundamental to creating the space and which strongly links it to landscapes, our approach to landscapes should be expanded to other senses too. The body should be considered as an extension of the surrounding landscape and the respective space in which there is a constant exchange of energy. The climatic conditions that become amplified in coastal frontiers could be used as a design tool.11 The contrasts between water, sand and air, temperatures, the alternating winds and shadows, lapping of the waves, the smell of seaweed and the salty taste of water allow one to experience sensations where sight is clearly of secondary importance.

Studies have shown that the so-called blue areas, that is, spaces near water help to prevent mental health problems.12 However, the ability to create spaces that are good for health, already spoken of by Vitruvius, has been lost over time. The paralysing sensory numbness and the resulting alienation from the environment have been partly caused by contemporary architecture characterised by homogenised comfort and detachment from time and place.13

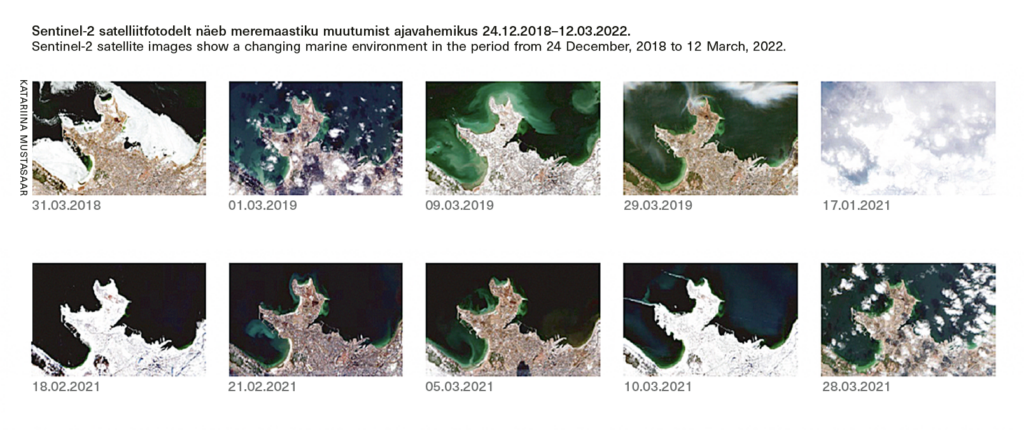

(Landscape) architecture that integrates

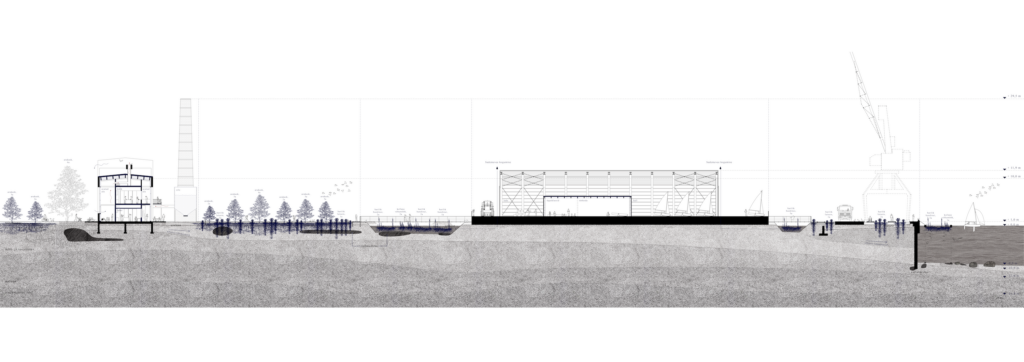

In my MA thesis defended at the Estonian Academy of Arts this spring, I envisioned how cleaning the polluted soil by means of phytoremediation technology could steer the transformation of a former industrial port area into a contemporary urban space.14 Phytoremediation, studied in Estonia at the TalTech Institute of Environment Technology, is a bioremediation technology using plants to break down pollutants on site and/or to absorb them from the environment.15 Eliminating the pollution cycling between the land and the sea by means of plants allows to point to the interconnectedness of natural and man-made environments. In the project, the characteristic landscape will emerge in the course of time, creating a new aesthetics for the given urban space. The project offers an alternative approach to designing urban environments that could be applied to remediating soils in former industrial areas along the Baltic Sea coastline.

Against a backdrop of global crises, volatile seascapes come to question the traditional separation of architecture and landscape architecture that has transpired over time. By considering the two integrally, we could build stronger links with the environment at large. By combining landscape, buildings, local characteristics and users, and by adopting a critical approach to the context of the project, architecture can provide accurate solutions benefiting both people and the environment. Similarly, small initiatives can have a positive impact on spatial development, even if limited to inspiring change and raising environmental awareness.

Vestre Fjord Park, designed by ADEPT, near Aalborg in Denmark illustrates the Nordic symbiosis of building and landscape in which the modesty of architecture allows to bring the surrounding nature to the fore. The articulated building set on an isthmus is covered with a roofscape enhancing the area’s links with the sea both symbolically and physically. By providing multiple access points and areas to the sea, it allows all users to experience the diversity of the seaside space while also serving as a functioning infrastructure and communal meeting place.

Immanent landscapes can also be achieved by using only artificial elements. Designed by Helen & Hard, the Geopark in Norway’s oil capital Stavanger creates playful attractions from objects abandoned by the oil industry. The form of the park is a reproduction of the Troll field oil reservoir in the Atlantic Ocean revealing the geological layers hidden under the seabed. It was created digitally in cooperation with local experts and children who helped to choose the location of the skate park and the street art walls. The originally temporary playground has become a permanent leisure area making its users think about the destructive impact of industry on nature. In this context, Geopark as a park introducing geological heritage acquires a whole new meaning.

KATARIINA MUSTASSAAR is an architect and co-founder of architecture practice Stuudio Kollektiiv.

PUBLISHED: Maja 114 (autumn 2023) with main topic ISLANDS

1 ‘Eestirootslased’, online Eesti Entsüklopeedia.

2 State of the Baltic Sea—Second HELCOM holistic assessment 2011–2016. Baltic Sea Environment Proceedings 155, HELCOM (2018), 27.

3 Christophe Girot, ‘Immanent Landscape’, Harvard Design Magazine 36 (2013).

4 ‘About the Commons’, website of the International Association for the Study of the Commons.

5 HELCOM Baltic Sea Action Plan –2021 update, HELCOM (2021), 50.

6 Eesti mereala planeeringu seletuskiri, Ministry of Finance and Hendrikson & Ko (September 2021), 65–73.

7 ‘The Helsinki Convention’, HELCOM website.

8 Jānis Ušča, ‘The Baltic Sea: Our Collective Resource’, The Baltic Atlas, edited by Jennifer Boyd (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016), 157.

9 Silvia Benedito, Atmosphere Anatomies: On Design, Weather, and Sensation (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2021), 26.

10 Hannes Tõnisson, ‘Eesti rannikute ajalooraamat aitab vaadata kliimamuutuste tulevikku’, Postimees Teadus, 20.07.2022 [2019].

11 Silvia Benedito, Atmosphere Anatomies: On Design, Weather, and Sensation (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2021), 22– 27.

12 Grete Arro, ‘Suured pisiasjad linnaruumis’. Public lecture in the series ‘Elav ruum’, e-lecture, Estonian Museum of Architecture, 10.03.2021. Youtube video, from 9 min.

13 Luis Fernández-Galiano, ‘Soojuslik ruum arhitektuuris: arhitektuur ja tuli Vitruviusest Le Corbusier’ni’, Arhitektuur ja soojusmõõde, edited by Neeme Lopp (Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Arts, 2018 [1991]), 10.

14 Katariina Mustasaar, ‘Tööstusjärgne meremaastik: Paljassaare sadamaala taimtervendamine’ (MA thesis. (Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Arts, 2023).

15 Sergei Preis (professor and head of Laboratory of Environment Technology at TalTech), conversation with the author, 21.02.2023 and 17.04.2023. The author’s notes.