Designing in close collaboration with what the material provides, ’Working Stone’ summer school uncovered some interesting alternative approaches to productive reuse, write Juliet Haysom and Thomas Randall-Page.

In the summer of 2023, Tom Randall-Page and I directed the Architectural Association (AA) Visiting School ‘Working Stone’. Tom and I are both Studio Tutors at the AA, and both have personal connections to stone. My family run Haysom Purbeck Stone, a long-established quarry and masonry works in Purbeck, Dorset; and Tom regularly collaborates with his father, sculptor Peter Randall-Page.

We both also share an interest in introducing students to stone. Stone has been central to architecture for as long as we have archaeological records of. However, in the past century it has been largely relegated from its former position as primary structure to a lesser role as a surface finish, cladding and paving over concrete and steel skeletons. Even though the AA has excellent workshops for timber and metal fabrication and concrete casting, it has no facilities for working with stone. This is typical of architecture schools, and the reasons are understandable—stone is heavy, conventional ways of working with it are relatively slow, the resulting dust requires specialist equipment such as water cutting to mitigate health risks, and it is not as readily available as other building materials. However, the result is that this material remains mysterious to architecture students. ’Working Stone’ aimed to address these issues, offering students an opportunity to undertake a design brief in which stone was the main protagonist, and to gain familiarity with stone masonry tools and processes by being immersed in a fully-equipped masonry workshop for the duration of the project.

The summer school’s brief was to design and build a bus shelter out of Purbeck stone for an existing bus stop next to Acton in Purbeck. The plan was to assemble our shelter within the Haysom Purbeck Stone masonry workshop yard during the course, and then subsequently apply for planning permission. If that succeeds, we aim to reconstruct the shelter in its intended location in 2024.

We started off by familiarising ourselves with the local landscape. The Isle of Purbeck is a peninsula towards the eastern end of the Jurassic Coast UNESCO World Heritage Site in Dorset, on the south coast of England. Its numerous beds of Jurassic limestone make for excellent building stone, and the area has been defined by quarrying for centuries. We believe that the geological and landscape context of stone is important to understand; without that, the material becomes another abstract product. The quarry context makes clear the physical limitations of the material—both in terms of block size, and its finite availability. The stone quarried on the Isle of Purbeck has been eroded by the sea to the east, south and west, while in the north, the beds dip so deeply that their extraction is commercially unviable. The Visiting School worked in two of Haysom Purbeck Stone’s quarries and masonry works.

We introduced the students to masonry tools and workshop processes. Students were shown how to dress a quoin, hand-tool a textured surface, use the air chisel, use a variable speed sander for sanding and polishing; they were shown how to split a block using plugs and feathers, and how to use the table saw. This was not done with the unrealistic expectation that they would immediately gain masonry skills, nor that they would require masonry skills to be an architect. Rather, by facilitating direct contact with stone, tools, and techniques they were meant to gain a level of tacit understanding of what it takes to process raw stone into an architectural component. We believe this gives them an enhanced appreciation of stone as a material, and of the associated craft processes, which we hope will assist them in navigating design and procurement conversations and decisions in practice.

Photo: AA Working Stone

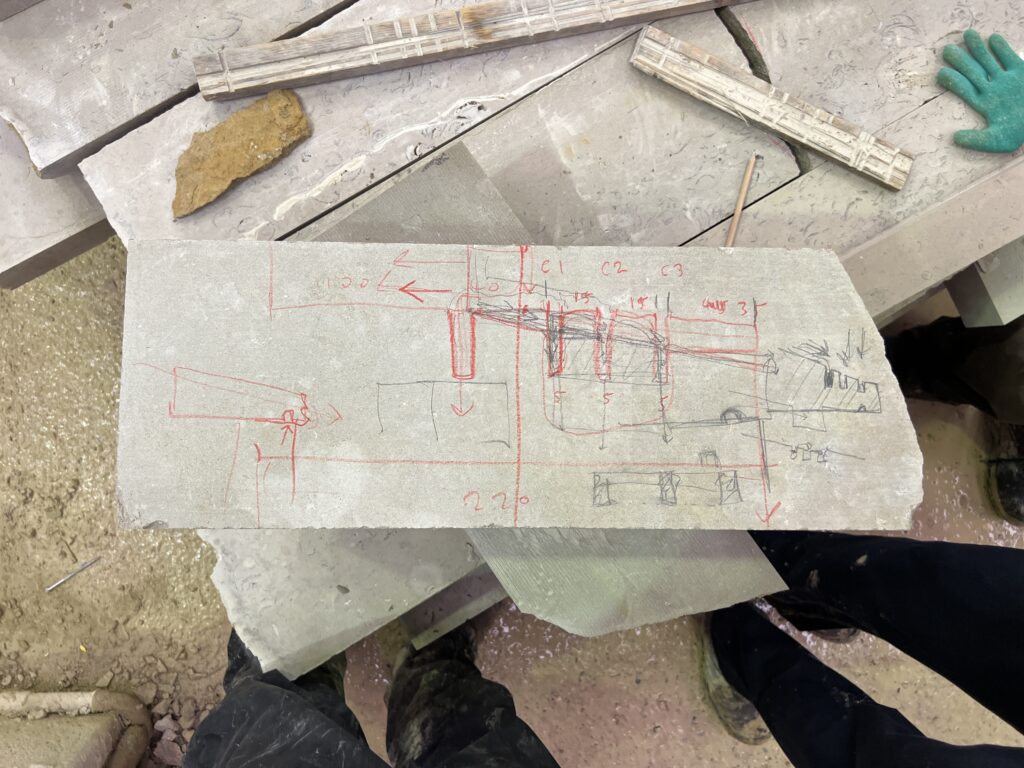

Design work began through group review and discussion, hand-drawing and simple model-making. We looked at the waste products in the masonry yard, and the surplus and off-cuts from recent jobs to explore the potential use of these otherwise undervalued materials. Our designing and making process ended up going back and forth between digital models, paper models, and stone as-found. We worked within the creative constraint of what was available and close at hand so we could make most efficient use of these elements. This was unusual, because in most design projects you don’t get that immediacy or reciprocity with available materials. Usually it is a much more linear stage of works, in which designing and making are separated—pulled apart in time, and also carried out by different people, at different locations. Our approach meant that students could take advantage of individual qualities of the stone rather than just its generalised properties. For example, cutting into several pieces of Spangle, we found ammonites that had beautiful glittering interiors which might otherwise have gone unused because the designer would not have been able to factor those in. Also, the natural face of the block has a characterful but irregular texture, so it is usually cut off and discarded. The students really enjoyed making use of these in a formal way.

Photos: AA Working Stone

We worked through a number of iterations of our designs. At St Aldhelm’s Head quarry, where the Purbeck-Portland beds are quarried, there were two ongoing commercial jobs. One of these was producing quite a large volume of cuboid off-cuts with consistent dimensions. The other set of off-cuts came from a cladding job for the Natural History Museum in London, and these were longer and thinner. Both sets meant that there was a lot of material cut with at least two dimensions in common which we could adapt with minimal additional processing. Students worked in two groups—one group carefully arranging found off-cuts into a structure, and the other splitting a monumental piece of stone to produce ‘bookends for the front of the shelter, and to produce the support for the roof. By the end of the second week, surprisingly, despite being behind our planned schedule, we ended up being able to construct almost the entire shelter.

We think it was a successful project. The shelter is practical and coherent, with distinctive features that were encountered by chance and incorporated through students’ discerning arrangement. But what I also think ended up being exciting is the opportunistic improvisational nature of our methodology, and what it offers as a model of an unconventional, but potentially more sustainable kind of design practice. So much construction waste—which contributes so much to the climate crisis—is due to the unwieldy gap between the moment when off-cuts and surplus are produced and the opportunity for them to be used or reused elsewhere. This is because their reuse would require production of bespoke inventory and storage for resale. This is slow, inefficient and therefore currently economically unviable, leading to so much usable construction material being disposed of and wasted.

By working within the masonry workshop yard and in conversation with the stonemasons, we were able to adapt and make use of available materials that would otherwise have been stockpiled or discarded. A month earlier or a month later these materials would be different, so our design emerged from a unique range of geometries. Although we adopted a way of working that might be quite unconventional, we are optimistic it can facilitate some interesting alternative approaches to productive reuse within the stone industry and elsewhere. We are now hoping that, subject to gaining planning permission and raising funds to cover installation costs, we will be able to permanently install the shelter in its intended site so that people waiting for the bus in Purbeck could enjoy it for years to come.

JULIET HAYSOM is an artist and tutor at the Architectural Association in London. Her work has a specific relationship with place, and the materials found beneath our feet.

THOMAS RANDALL-PAGE has a London design practice of the same name. He is a designer, maker, teacher and all-round enthusiast.

Working Stone 2023 students: Deima Ambrazaityte, Nikola Da Silva Azevedo, Blanche Howard, Jack Jones, Nikola Kechrimpari, Bohdan Kryzsanowsky, Georgina Lombardero, Ismail Mir, Adam Mundzic, Berrie Oh, Felix Sagar, Celine Topsakal, Henri Uijtterhaegen and Hiro Yamane.

With thanks to Haysom Purbeck Stone; The Stone Federation of Great Britain; Szerelmey; Steve Webb, Director of Webb Yates; Georg Kusser, Director of Kusser Graniteworks; and artist Peter Randall-Page for their time and generous support.

HEADER photo by AA Working Stone

PUBLISHED: MAJA 1-2024 (115) with main topic STONE