Acting as material broker, Amaya Hernandez writes about saving more than 100 million years old stone from being ground into aggregate for a concrete planter.

I was a bit surprised that it took an overly enthusiastic architecture student to bring together demolition contractors, material resellers, stone conservationists, architects, and engineers in order to ensure the reclamation of a bunch of stones from a demolition site on Fleet Street in London in 2022. While I was working on my master’s thesis at the Architectural Association, certain events unfolded that not only made me realise the need for a new kind of consultant in our building industry, who would be responsible for managing the reclamation and reintegration of building materials, but also enabled me to identify the bottlenecks one must address before making reclamation of perfectly reusable materials—such as stone—a viable option today.

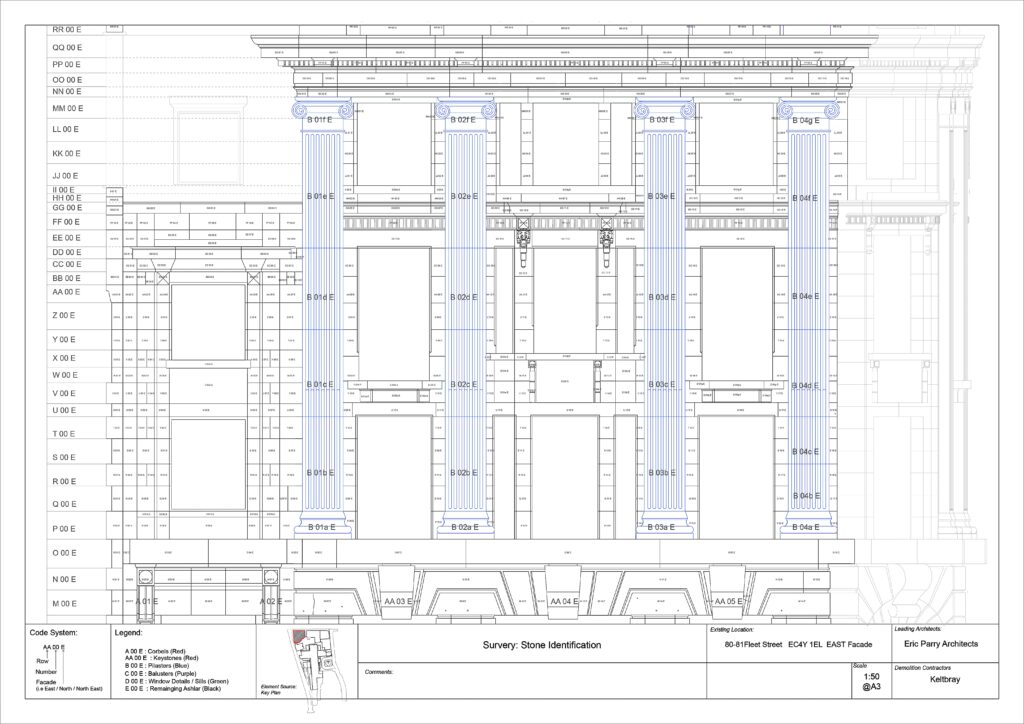

The narrative unfolds at the Salisbury Square redevelopment site on Fleet Street in Central London. Here, the impending demolition of nine buildings set the stage for my year-long attempt to reclaim Portland stone from the old buildings at 80–81 Fleet Street. With less than 1% of building materials typically reclaimed after demolition, it was surprising for me to discover that the planning application documents for the project explicitly mentioned intentions to reclaim Portland stone, limestone, and marble facades from the existing buildings for on-site and/or off-site reuse without downcycling them. What first seemed to be a sign of progress quickly proved to be nothing more than business as usual. Upon investigating whether the activities that the document seemed to suggest are actually taking place, I quickly learnt that the demolition plans were going forward as usual because reclamation of stone was subject to being procured by a buyer, and no buyer had been found, probably because no stakeholder was actively looking for one.

Before proceeding, it is important to recognise the difference between reuse and recycling in the context of building materials—understanding these nuances is vital for sustainable practices in construction. Reuse involves using materials multiple times without significant alteration, aiming to extend their lifespan and minimise waste and energy consumption. Recycling, on the other hand, involves collecting, breaking down, processing, and transforming used materials into new products or ‘raw’ materials. Recycling involves high energy consumption and often downgrades the quality of the materials, whereas reuse does not.

On the Salisbury Square redevelopment site, despite the stone’s immense capacity for reuse, the architects and stakeholders thought it best to crush the stone into gravel and use it as aggregate for concrete planters in the new development. The grimness of this outcome is heightened upon understanding how Portland stone came to be.

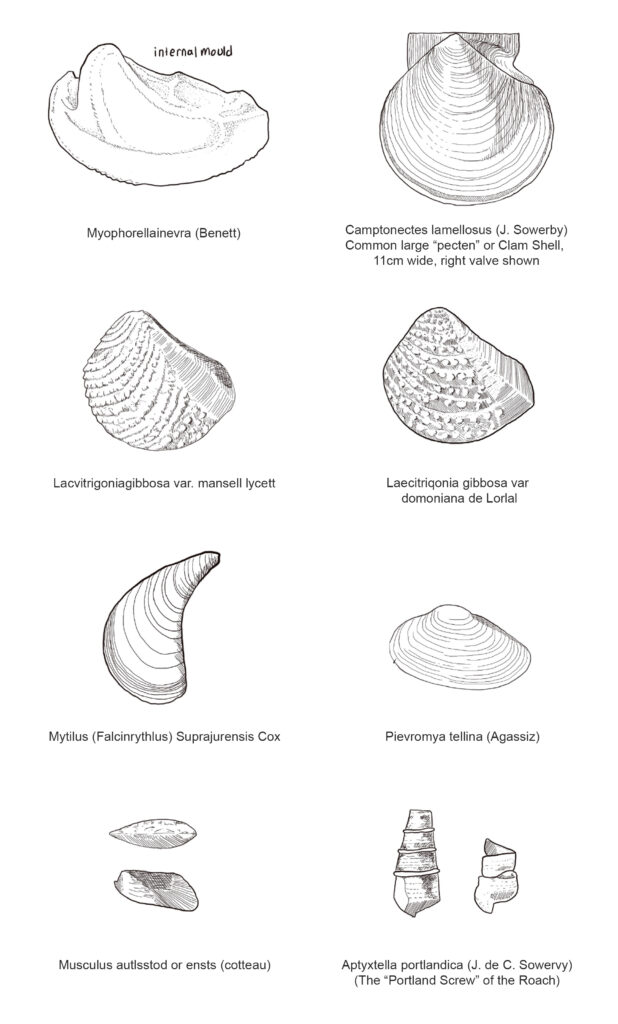

The story of Portland stone begins some 145 million years ago, in the Jurassic Period, when the Earth’s landscapes were drastically different from what we know today. At that time, the region that would later become the Isle of Portland in southern England was submerged in a vast shallow tropical sea.

In an environment resembling the Caribbean Sea today, tiny marine organisms, such as molluscs and foraminifera, lived harmoniously, leaving behind their skeletons to dance to the currents, back and forth on the ocean floor. Calcium carbonate coated the molluscs’ bare shells and transformed them into tiny beads known as ooids. Over countless millennia, layer upon layer of these organic remains accumulated on the sea floor, creating a bed of sediment that would lay the foundation for the future Portland stone. In due course, the sea retreated, and the once-submerged sediments were exposed to the whims of the elements. Here, the magic of geological alchemy unfolded. Under the gentle caress of time and pressure, the loose sediments underwent a miraculous metamorphosis. The calcium carbonate from the ancient marine life transformed into a resilient, creamy-white limestone.

The stone, now rich in history and character, emerged from the depths, revealing itself to the world. Its beauty and durability did not go unnoticed by humankind, and soon it became a cherished building material. From the grandeur of St. Paul’s Cathedral to the elegance of Buckingham Palace, Portland stone adorned some of the most iconic structures, each carrying a silent testimony of the ancient marine ballet that birthed this unique geological wonder.

And so, Portland stone stands as a testament to the profound tales woven into the very fabric of the Earth. A tale of long-gone sea creatures, of epochs that have shaped our world, and of a limestone that transcends time—a geological marvel with a story as enduring as the stone itself. Could the same be said about concrete planters?

Not only the history, but also the makeup and structural integrity of Portland stone are magnificent. In the case of 80–81 Fleet Street, it remained a perfectly reusable building material. 80–81 Fleet Street was a bank building, built in 1924 after the passing of the London Building Act of 1909—which essentially sanctioned engineers to use steel columns within the external frame to take the floor loads—but before engineers began to reduce the thickness of masonry. This meant that even though the building had a steel frame, the Portland stone remained a thick ashlar. The thickness of the stone has proven to be a double edge sword—on the one hand, more material means more possibilities for material re-manipulation, but on the other, it increases the weight of the stone and by extension the time it would take to bring the stone down to the ground safely and without damage during disassembly.

The speed at which demolition companies are expected to complete their work is suffocating many, if not most, chances for proper reclamation of materials. The initial reclamation ambitions that many deem to be common sense quickly become unobtainable as tight deadlines and lack of policy enforcement authorise our industry to be one of waste and missed opportunities. In the case of this particular project there were two notable oversights I wish to bring to light.

Firstly, the leading architects commissioned to design the City of London’s new Justice Quarters, due to replace the Salisbury Square buildings, did not pay any notable attention to the fact that they were demolishing a Portland stone building and replacing it with a Portland stone building without reclaiming any of the existing Portland stone on site. And this despite the fact that there were written intentions in the planning application documents to reclaim the Portland stone without downcycling it.

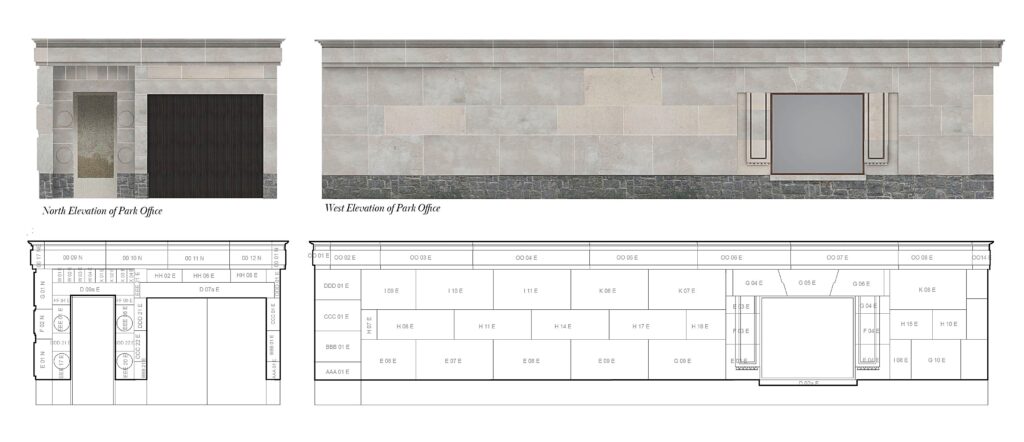

Secondly, while the City of London was planning to demolish 80–81 Fleet Street and was seemingly having difficulty finding a buyer for the Portland stone, it was also simultaneously looking for reclaimed stone for another of their redevelopment projects at Bank Junction in Central London, a measly 1.8 km away from 80–81 Fleet Street.

In the case of the architects, one of their reasons for not reclaiming the existing Portland stone was their assumption that the old building only contains ornamental stone which would not fit the overall aesthetic of their proposal. I knew this to be an incorrect assumption, so I took it upon myself to prove to them that the existing stone could fit within their design. Upon demonstrating this to the architects, however, I was informed that it was simply too late to integrate the existing stone as the project was in a late stage, too far along in the process to reconsider its designs.

I catalogued the stone further and started contacting stone conservationists, stonemasons, stone enthusiasts, geologists, resellers, demolition contractors, demolition operatives, sustainability managers, architects, and their receptionists. I contacted everyone from established quarries to random people on Facebook. I sent 93 emails, made 38 phone calls, did 22 site visits, and recorded over 5 hours of audio from various interviews—all with the goal of finding a buyer to reclaim the stone. This journey of designing proposals that would reintegrate the specific stone and reaching out to any potentially interested party led me to the conclusion that there is an actor missing in the building industry, an actor for whom I have coined the term Material Broker.

A Material Broker would facilitate negotiations between material resellers, demolition contractors, architects and their clients to promote the reclamation of our existing building stock. Ensuring material salvage in a project would be the sole responsibility of this consultant. Currently, material reuse ambitions might start out quite strong, as exemplified in the case of 80–81 Fleet Street, but then become dependent on the stamina of actors with a different set of key responsibilities in the project’s ecosystem. Inertia takes hold as the actors become increasingly busy with their main tasks, and the reuse ambitions begin to crumble, until all is demolished and nothing (or in some brighter cases very little) is reclaimed. This is why the Material Broker as a mediator would be beneficial in making an active change in the building industry.

I am happy to report that in the end, I was successful in finding a buyer for some of the stone. Firstly, 500 sqm of Yorkstone paving was reclaimed from the site. Secondly, the Portland Sculpture and Quarry Trust understood the value of my efforts and managed to reclaim the stones of the main entrance of 80–81 Fleet Street. The entrance was carefully deconstructed, palleted, and returned to the Isle of Portland to be reconstructed as a monument. I am eternally grateful to the trust for helping me prove the positive impact that a Material Broker can have, although I would have enjoyed seeing the stones remain in London and integrated into other sites to demonstrate that reclamation is not only possible today but truly a way forward.

In essence, the story of ‘Sisyphus and the Portland Stone’ is a call to action for the building industry and a call to imagine a future where the creative mind of the architect can be a catalyst for effective climate change strategies without compromising on our commitments to good design. It urges us to reconsider our approach to materials, acknowledge the untapped potential of reclamation, and embrace a more sustainable future guided by dedicated figures like the Material Broker. The project journey, while convoluted, offers a glimpse into the transformative possibilities in prioritising the innovative reuse of our existing building stock.

AMAYA HERNANDEZ is an architect investigating reuse and natural building materials, the landscapes they come from, and the tradespeople that known them best.

PUBLISHED: MAJA 1-2024 (115) with main topic STONE