Limestone in Estonian Construction and Architecture in the 20th Century

Due to its wide availability and long tradition of use, limestone is a central figure in the history of Estonian construction and architecture. Whether it be dressed or sawn, in load-bearing walls or façades, buildings with a military function or official function, limestone is almost omnipresent in our stone buildings, especially in northern Estonia and on the islands. In the context of 20th-century Estonian architecture, limestone figures most prominently in the works of Herbert Johanson as well as Raine Karp. The symbolic role of limestone in Estonian spatial culture grew vigorously in the decades that preceded and followed the restoration of Estonian independence. On the initiative of geologists, architects and historians, this more than 400-million-years-old natural stone was put down as a carrier of Estonian national culture.

Building material

The term ‘limestone’ can be used as a general term for several kinds of stone that have been used for building in the Estonian territory throughout centuries.1 Along with wood, limestone can be considered the most common natural building material in the region. The most widely used kinds are Lasnamäe construction limestone and Saaremaa dolomite. Vasalemma marble is also well-known. In terms of strength of materials, limestone works best under compression, so the best way to use it in load-bearing structures is masonry, whether it be in walls or foundations.2

Some limestone structures in Estonia, e.g., stone-cist graves, date back to the ancient period. Stone structures began spreading more rapidly in the 13th century with Christianisation; limestone became the main building material besides brick in fortifications and sacral architecture as well as urban stone buildings. Due to Estonia’s particular geological base, limestone buildings are most widespread in northern Estonia and on the islands, where the stone is closest to the surface, and thus, most readily available.

The role of limestone as a building material changed significantly in the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, when the development of construction science and modernisation of industry boosted the spread of metal and concrete structures. From there on, the use of limestone as a structural material gradually receded, but the stone remained a widely used raw material for various constructional and decorative details.

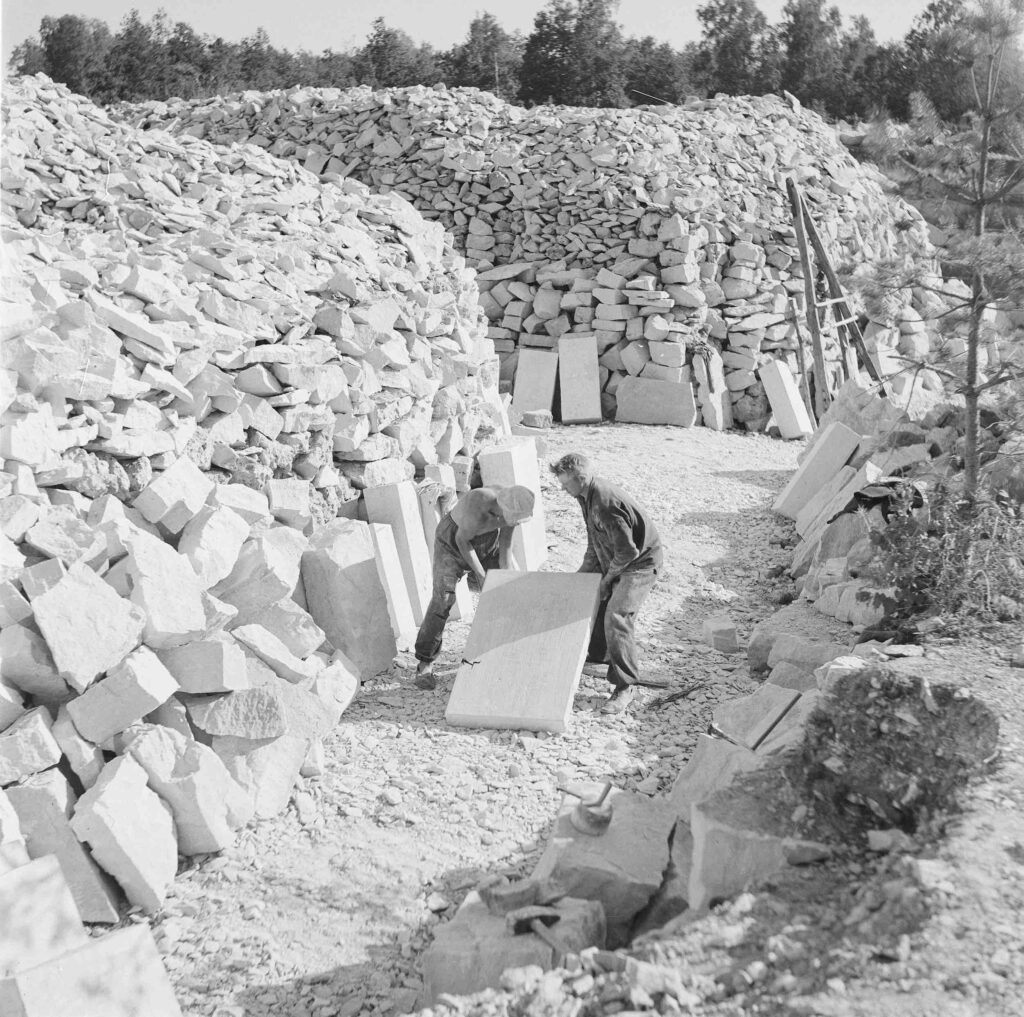

Shaping limestone into different building materials has always been a laborious process. Creating a product out of natural stone requires a workforce with specialised skills and knowledge. This is why high-quality construction limestone was quarried manually for centuries. Knowledge was passed on mostly by word of mouth in the course of practical work. The mechanisation of limestone industry began in the Estonian territories in the late Tsarist period, but did not become very widespread even in the independent republic.

Up until prefabricated concrete products appeared in the 1960s, limestone remained the main type of stone for building foundations, but it was also used for façade cladding, stair steps, cornices and lintels and other building products with a specific function. In the early 1960s, the last major quarry for construction limestone in Tallinn was closed. With the introduction of concrete products, the share of limestone industry in the construction sector decreased significantly. From there on, most of the quarried limestone was turned into crushed stone, for the latter was needed by the concrete industry. Only the production of façade cladding out of Saaremaa dolomite remained at a significant scale, and continues also today. Nowadays, limestone is used mainly as a finishing material in Estonia.

Photo: Eesti ajaloomuuseum

Limestone functionalism

One of the most unique manifestations in the 20th-century Estonian architecture is limestone functionalism—an architectural phenomenon that emerged in early-1930s Tallinn and combined the techniques of modernist architecture with bulky façades made of dressed limestone. Architect Herbert Johanson designed the largest number of such buildings. His most well-known works in this style are Lasnamäe Elementary School (1932–36, today Tallinn School of Service), Tõnismäe Secondary School of Homemaking (1935–37, today TalTech Tallinn College), chapels in Liiva and Metsakalmistu cemeteries (1934–35 and 1935–36, respectively) and Tallinn Fire Station (1936–39).

Architectural historian Mart Kalm, who studied Johanson’s limestone architecture thoroughly already in the mid-1980s, includes also the (unbuilt) monumental new Tallinn Town Hall (1934–35), dressing room building in the yard of Tallinn Secondary School of Science (1938) and pavilion and retaining walls in Hirvepark (1936–39) in the list.3 Johanson also designed Kalasadama dressing room building (1936) and a number of other small buildings and facilities, the appearance of which was largely by defined limestone masonry—Snelli Stadium dressing room building (1933), Tondi Train Station (1936) etc.

Although Lasnamäe Elementary School, the original design of which was completed in 1932 and the building itself in 1936, gets usually highlighted as the earliest examples of limestone functionalism, Johanson actually came to combine dressed limestone and modernist architecture somewhat earlier. The designs for the extension of August Jürgens’ iron bed frame factory on Tartu hwy in Tallinn are from 1929–30.4 The extension was completed in 1931 at the latest.5 The street-side volume of the complex is a limestone block that has simple decor (patterned brick frames of windows and doors, dentil frieze under the cornice) and vertical windows characteristic of earlier architecture, but whose cuboid form heralds the imminent arrival of a new architecture. The second and third floor of the tower-like volume each used to house a three-room apartment.

Photo: Rahvusarhiiv

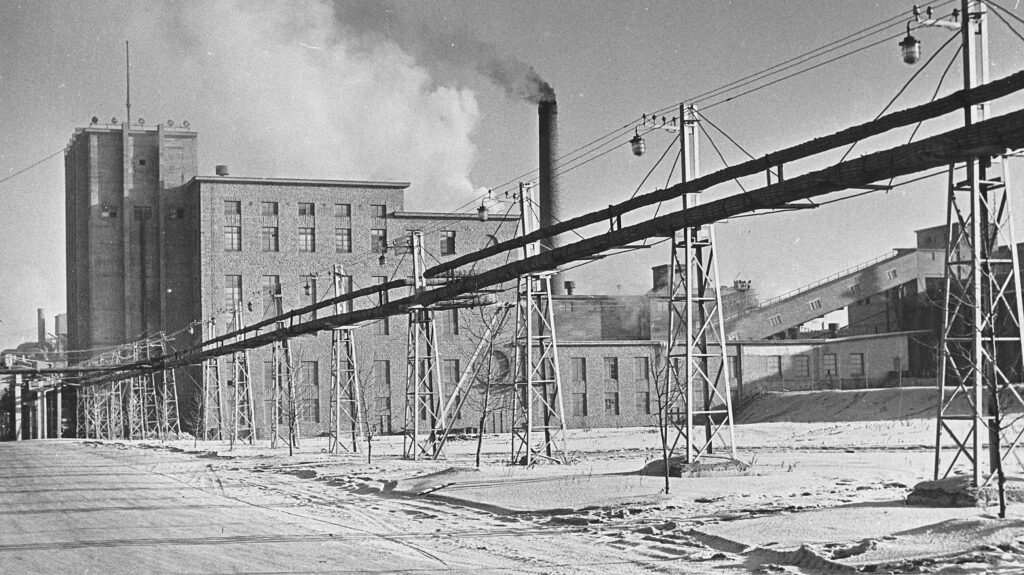

Other architects besides Johanson combined modernism and dressed stone façades much more seldomly in their work. One exceptional example whose authorship is still not definitively known is the new boiler house of Tallinn Power Plant. The author of the initial project (1932) is Eugen Habermann; the final version (1934) bears Johanson’s signature. Be that as it may, the building consists in a very skilful combination of constructional and architectural techniques, structure and abstract ornamentation. The slim support pillars and wide concrete cornice protruding from the limestone wall nicely accentuate the volume of the boiler hall, leaving the wall surfaces to small-squared windows whose placement is reminiscent of the cross-section of an I-beam.

Mature Johanson-style limestone use can be seen in the volume on the entrance side of the erstwhile Women’s Union’s Home Economics Institute (1937–39, currently the elementary grades building of Tallinn French Lyceum) in Tõnismäe, designed by Artur Jürvetson. Dressed stone façades achieve a monumental effect in modernist industrial buildings. Good examples of this are the phosphorite enrichment plant in Maardu, designed by Eugen Sacharias (then Saarelinn) (1940–41) and Kehra cellulose factory, designed by Johan Ostrat (1937–38).

Photo: Eesti ajaloomuuseum

Most of the buildings mentioned here are not built entirely of limestone. They mostly feature it in their façades, occasionally in both structural and decorative functions, but, in case of the buildings from the second half of the 1930s and onwards, more and more often as a merely decorative material. In industrial buildings, schoolhouses as well as smaller buildings, it was usual that the internal load-bearing structure—the columns and ceilings—were cast of monolithic reinforced concrete. Interior walls and dividing walls were mostly built of bricks, concrete blocks or wood. Thus, it could well be that in a building classified as limestone architecture, only its exterior walls and foundations are actually made of this material.

Limestone discourse and national narrative

In the second half of the 1930s, there was a lot of discussion on the need to look for such techniques and means of expression in architecture and construction that were specific to Estonian culture, meaning that a search for an architectural and constructional form for national culture was underway. Limestone was considered a dignified local material and its use was promoted with national building policies,6 but it was not necessarily highlighted as a direct symbol of national culture. The latter status was granted to limestone only in the 1980s and 1990s.

The early 1980s brought along a wider public debate over limestone as a local natural resource and a building material that has influenced our architecture. Geologist Rein Einasto, building historian Hubert Matve and architect Rein Zobel published a three-part series of papers ‘Limestone in Architecture and Estonian Limestone Architecture’.7 In addition to digressions into architectural history and geological specifics, they forcefully highlighted limestone as the national stone of Estonia, and suggested that it could be used more widely in construction once again.

Photo: Rahvusarhiiv

Einasto, Matve and Zobel did not precisely define how the relationship that Estonians have with limestone is somehow more special than the one that other peoples who lived or ruled here had. Their peculiar, positively mythologising limestone propaganda culminated during the new wave of national awakening, when in 1992, the Union of Estonian Limestone was founded, regular conferences on limestone began to be held, and the stone was declared the national stone of Estonia.8 An important follow-up to this process was the 1997 material and architecture exhibition ‘Estonian Limestone’ in the Estonian Museum of Architecture and Saaremaa Museum in Kuressaare, put together by Rein Einasto, Helle Perens and Karin Hallas-Murula.9 The star exhibit was a 15-metres-long limestone core drill from Väo quarry. Architecture critic Andres Kurg insightfully pointed out in his review how the exhibition brought the discussion of Estonian identity, archetypes and mythology to the level of materials.10

Photo: Hans Soosaar, Tallinna Linnamuuseum

Architects, too, were participating in the limestone debate already in the 1980s. One of their main points of contention was the aforementioned phenomenon of limestone functionalism. In the fourth issue of the almanac Ehituskunst (1988), Mart Kalm published the first thorough account of Herbert Johanson’s limestone architecture and gave it a striking, but controversial name—limestone functionalism.11 It was controversial because the bulkiness of dressed limestone did not match well with the more avant-garde examples and programmatic views of the high modernism (functionalism) of Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Aalto, etc.

Photo: Haapsalu ja Läänemaa muuseumid

In addition to his intention to create an intrigue of architectural history, Kalm nevertheless also had rational arguments—limestone was a local and readily available material in the 1930s, and there were skilled workers who could process and use it. The construction limestone for Lasnamäe Elementary School, for example, was quarried from the foundation pit of the very same building. The pragmatic approach to using building materials and workforce fit well with the principle of rationality in functionalism.

Over the years, the main critics of Kalm’s account of limestone functionalism have been Karin Hallas-Murula and, to a lesser extent, Krista Kodres. Their disagreements mostly revolved around issues in the history of style. While Kalm finds that Johanson’s limestone buildings can safely be classified under functionalism, Hallas-Murula associates them rather with the German national socialist architecture of the second half of the 1930s.12 Krista Kodres finds that Johanson’s limestone architecture should be viewed on the background of Art Deco.13

Kalm and Hallas-Murula might differ in their style-critical views, but both acknowledge the modern limestone buildings of the 1930s, especially those designed by Herbert Johanson, as outstanding examples of Estonian architecture of their day that were responsive to the demand for nationalism that was in the air. Thus, their rhetoric is not that different from that of Einasto, Matve and others who, in the rush of national awakening, seemed to be looking for the DNA of Estonianness in limestone.

CARL-DAG LIGE is an architecture critic and historian. As a doctoral student and junior researcher at the Estonian Academy of Arts, he is interested in the history of modern architecture and its connections to engineering.

HEADER: Quarrymen in Kaarma quarry, Saaremaa, 1939. Photo: Carl Sarap, Tallinna Linnamuuseum

PUBLISHED: MAJA 1-2024 (115) with main topic STONE

1 In this section, I rely mainly on Hubert Matve’s manuscript Eestimaa paas [Estonian Limestone], Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum EAM.20.2.24.

2 On the types, physical properties and constructional uses of limestone, see Lembi-Merike Raado, Ehitusmaterjalid [Construction Materials], Tallinn: Sihtasutus Professor Karl Õigeri Stipendiumifond, 2018.

3 Mart Kalm, ‘Herbert Johansoni paefunktsionalism’ [‘Herbert Johanson’s Limestone Functionalism’, Ehituskunst 4, (1984/1988).

4 I am grateful to Rain Vaikla for pointing this out.

5 This is confirmed by the fact that photos of the newly-completed buildings were published in the 1931 compilation Eesti tööstus & kaubandus: sõnas ja pildis [Industry and Commerce of Estonia: In Words and Images], where an overview of Jürgens’ bed factory can be found on pp. 34–39.

6 Karin Hallas-Murula, ‘Riik ja arhitektuur. Konstantin Pätsi ehituspoliitika 1918–1940’ [‘State and Architecture. Construction Policies of Konstantin Päts in 1918–1940’], Kunstiteaduslike Uurimusi 25, no. 3–4, (2016).

7 Sirp ja Vasar (3, 17 and 24 July 1981). See also Rein Einasto, Hubert Matve, ‘Kas don Quijote on jälle liikvel?’ [‘Is Don Quijote at It Again?’], Sirp (13 and 20 July 1984).

8 Union of Estonian Limestone website https://paeliit.wordpress.com/ [viewed 29 February 2024]. The declaration of limestone as the national stone at the 2nd Estonian Limestone Congress on the 24th of April in 1992 was even published on the front page of Sirp in an abbreviated form – see Sirp (8th May 1992).

9 Eesti Paas [Estonian Limestone], exhibition catalogue, ed. Rein Einasto, Karin Hallas-Murula (Tallinn: Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, 1997).

10 Andres Kurg, ‘Ehitatud paest’ [‘Built out of Limestone’], Sõnumileht (24 June 1997).

11 Mart Kalm, ‘Herbert Johansoni paefunktsionalism’. The term ‘limestone functionalism’ had been used already in 1937 by intellectual Harald Paukson. See Harald Paukson, ‘Pealinna ülesehitusest’ [‘Building the Capital City’], Varamu 7 (1938).

12 See Karin Hallas-Murula, Funktsionalism Eestis [Functionalism in Estonia] (Tallinn: Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, 2002); Karin Hallas-Murula, 101 Eesti arhitektuuriteost [101 Works of Estonian Architecture] (Tallinn: Varrak, 2012).

13 Krista Kodres, ‘XX sajandi Eesti arhitektuur’ [‘20th-century Estonian architecture’], Sirp (1 March 2002).