Jakob D’herde explores homemaking in one’s later life by drawing upon the findings of his socio-spatial doctoral research project ‘Living (at) Home: On Older People’s Making of Home and Dignity’. He argues that homemaking is a continuous negotiation process between a dwelling and a person’s image of home. When this negotiation is successful, the home and dwelling can be conflated into what he calls the househome.

Independence, autonomy, as well as individual action and responsibility are all highly valued virtues in Western societies.1 Thus, older adults in the West attempt to retain them as much and as long as possible. The strategy called ‘ageing-in-place’ reflects these values as it aims to support older people in continuing to live ‘in the community, with some level of independence, rather than in residential care’.2 Over the past few decades, this strategy has become the central eldercare paradigm in many countries, including Belgium.

Unfortunately, the policy’s translation from theory to practice does not come without problems. In Flanders, the Dutch-speaking region of Belgium, ageing-in-place emphasises independence specifically by keeping older adults in their long-term dwellings. The broad, varied interpretations of independence are thus narrowed down to the purely spatial construction of the dwelling. This ‘Flemish translation’3 makes a number of assumptions about the relationship between the home, the dwelling, and notions like freedom and independence.

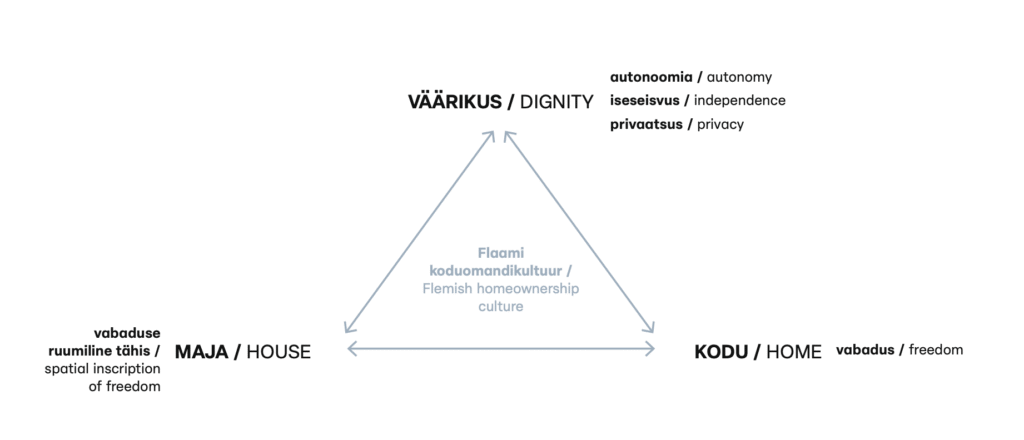

Flemish culture: the house/home

‘Home’ is a difficult concept to define. Some scholars describe it as a feeling related to safety, belonging, and privacy,4 while others point out its tyrannical and exclusive qualities.5 Some argue that home is inherently spatial, while others declare that it needn’t be linked to any particular space at all.6 To date, there is no theoretical consensus on the spatial aspects of home.

Outside of the academic or theoretical realm, home is often conflated with the dwelling. This is certainly the case in Flanders, where the words for house, huis, and home, thuis are etymologically connected: thuis literally translates into ‘to the house’. Given the culturally intertwined meanings of the two concepts, I propose the term ‘househome’ to describe their conflation. Moreover, following more than a century of politically supported homeownership,7 Flemish culture has strongly attached the notions of freedom, independence, privacy, and autonomy to the dwelling, which became a ‘spatial inscription of freedom’.8 In fact, I found that owning one’s own house has become a norm of societal prestige or dignity. The statistics show as much: Flemings are predominantly homeowners, especially people older than 65, of whom 75 percent own the dwelling they live in.9

The antithesis of this ‘househome’ is the nursing home; in multiple home interviews with older Flemings a comparison was made between living in one’s own house, and being lived in a nursing home. It seems that most compare a move to residential care with being stashed away in a small room where they must obey every rule imposed on them. They expect that they will no longer be able to choose when they wake up, what and when they eat, and where to go; in short, the nursing home is represented as a total loss of freedom. Hence, it should come as no surprise that these older adults overwhelmingly wish to stay out of residential care. Staying in one’s own house (whether as an owner or a renter) is equated to retaining one’s freedom. However, based on my research findings, I would strongly argue that the dwelling can only be conflated with the home insofar as it affords its inhabitants freedom. When the dwelling becomes a barrier to its inhabitants’ freedom, it ceases to be a home.

A home is ´made´

When a househome has been established, the societal assumption is that this result is final. Following architectural theorist Hilde Heynen, I argue that home is not static, but dynamic. As the verb homemaking implies, home is not a ‘stable situation of being’, but rather ‘a continuous process of becoming’.10 A home is made throughout each and every day by its inhabitants, or, as Brun and Fábos say: ‘Making home represents the process through which people try to gain control over their lives.’11

Throughout most of our lives, we humans adapt our living environment to suit our needs and wants, to feel safe—in short, to feel at home. However, it seems that society assumes that older people must feel at home where they live. After all, once a person has lived somewhere for an extended period of time, they should feel at home there. Yet the ‘making’ of home does not (and should not) stop in later life—in fact, one could argue that it becomes even more important in later years, since getting old entails an increasing risk of losing control over one’s life, should one’s mobility decrease or mental health deteriorate. It is at this point that the dwelling becomes increasingly important. Can its spatial aspects continue to support older inhabitants in their homemaking?

The importance of spatial affordances

In the 1970s, American psychologist James J. Gibson put forth ‘the theory of affordances’,12 in which he implies a complementarity between animals and their living environments. An environment has affordances: it provides some real, physical conditions to the animals inhabiting it, and these animals have adapted to take advantage of some of these resources in the course of evolution. As such, affordances are both objective and subjective, or physical and psychological: they provide the framework for different behaviours.

A person’s living environment can be regarded from the same perspective: does it afford its inhabitants’ homemaking? The romantisation of one’s long-term dwelling as the most appropriate place to age and make one’s home in Flemish culture clouds discussions about its spatial affordances. Still, a full rejection of the emotional attachments of living somewhere for a lifetime also seems unfair.

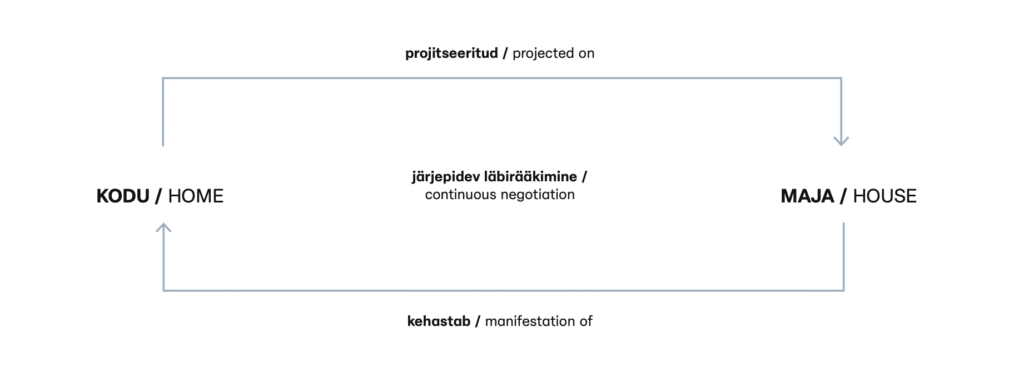

The househome negotiation

I propose a basic model of homemaking, strongly inspired by the psycho-geographical home.13 In this model, homemaking is considered a continuous negotiation between two entities: the spatial entity of the house, and the socio-cultural imaginary of the home. The house is the ‘naked’ dwelling, only accounting for its core spatialities, like its envelope, its thresholds, its dimensions, its openings and structure. It excludes its interior, furnishings and specific space plan (which are much more temporal and subject to change). The home, on the other hand, is what individuals imagine home to be like, informed by their personal experiences and lifestory, socio-cultural norms, beliefs, and so on. This imaginary of home is internalised and temporary—it is not stable over time, and evolves as people experience new things and undergo change themselves.

The model supposes that for the conflation of house and home to happen, two simultaneous preconditions must be met: the image of home must be projectable on the dwelling, and that dwelling in turn must be able to become a physical manifestation of the image. When one of these preconditions is not met, the conflation of house and home fails. This means that a person would have trouble with establishing a sense of home in the dwelling that is meant to function as their home.

Over time, most older people—especially if they have lived in the same place for years—manifest their internalised image of home through their dwelling ever more closely: their physical living environment may be as close to ‘home’ as it could be. They feel secure, they have the space to host family members during celebrations, they have their privacy, they are able to maintain their garden, etc. However, people’s relationship to their dwelling may change as they encounter changes and challenges in later life, like trouble maintaining the garden or the house at large, or taking care of themselves in this once-familiar environment. Their dwelling that used to be a place of safety, independence and freedom, may slowly turn into a cage, a place that actually starts to feel like a barrier to feelings of safety, comfort, and freedom. At this point, ‘home’ can no longer be made in the current living environment. Some change must happen: moving, renovation/retrofitting, getting formal or informal help—there is a plethora of options.

Regardless of which option seems best, it is important to stress that people do not age in a spatial vacuum: the place of aging matters.14 Their spatial environment should afford them the opportunity to make themselves feel at home. Luckily, most older adults I encountered during my research had been very successful in making their househome. Nevertheless, the takeaway is the following: when this continuous negotiation fails, action must be taken, and better sooner rather than later. Feeling at home can never be taken for granted. Regardless of age, it is a continuous process of becoming.

JACOB D’HERDE is an Belgian architect, scenographer and researcher. Having recently received his PhD from KU Leuven, he is now involved in artistic and scenographic research.

PHOTOS by Alissa Kiinvald

In A New Land Outside My Window (2014–15), artist Alissa Kiinvald (Nirgi) documented her grandmother after her move to Estonia from Ukraine. Kiinvald observed her grandmother’s struggles to feel at home in her new home, how her new surroundings were strange and uncomfortable to her, and how she didn’t feel she belonged. For Kiinvald who didn’t speak Ukrainian or Russian, the photos became a means to connect with her grandmother.

PUBLISHED: MAJA 2-2024 (116) with main topic OLD AGE

1 José Manuel São José, ´Preserving Dignity in Later Life´, Canadian Journal on Aging 35, no. 3 (2016): 332–347.

2 Janine L. Wiles, Annette Leibing, Nancy Guberman, Jeanne Reeve, Ruth E. S. Allen, ´The Meaning of ´aging in place” to older people´, The Gerontologist 52, no. 3 (2012): 357–366.

3 Jacob D’herde, ´Living (at) Home. On Older People’s making of Home and Dignity´ (2024).

4 Stephen M. Golant, ´Aging in the Right Place´ (Health Professions Press, Inc., 2015).

5 Mary Douglas, ´The Idea of a Home: A Kind of Space´, Social Research 58, no. 1 (1991): 287–307.

6 Paolo Boccagni, ´Migration and the Search for Home: Mapping Domestic Space in Migrants’ Everyday Lives´ (Palgrave Macmillan US, 2017).

7 Pascal de Decker, Bernard Hubeau, Ilse Loots, Isabelle Pannecoucke,

´Zo lang de leeuw kan bouwen…: Liber amicorum prof. dr. Luc Goossens´ (Antwerpen: Garant, 2012).

8 Maria Kaika, ´Interrogating the geographies of the familiar: Domesticating nature and constructing the autonomy of the modern home´, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28, no. 2 (2004): 265–286.

9 Isabelle Pannecoucke, Pascal de Decker, ´Woonsituatie en –dynamieken bij ouderen: Blijven of verhuizen? Steunpunt Wonen´ (Leuven: Steunpunt Wonen, 2017), 18.

10 Hilde Heynen, ´CODA: About the Displacement of Home´, Making Home(s) in Displacement, toim Luce Beeckmans, Alessandra Gola, Ashika Singh, Hilde Heynen (Leuven University Press, 2022), 395–416.

11 Cathrine Brun, Anita Fábos, ´Making Homes in Limbo? A Conceptual Framework´, Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees 31, no. 1 (2015).

12 James J. Gibson, ´The Theory of Affordances. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception´ (New York: Psychology Press, 2014).

13 Sigal Eden Almogi, Tovi Fenster, ´The Psycho-Geographical Home: ´Homemaking´ In the Frontier´, Home Cultures 17, no. 1 (2020): 45–68.

14 Emma Volckaert, Pascal De Decker, and Elise Schillebeeckx, ‘Older people’s experiences of informal care in rural Flanders, Belgium’, Journal of Depopulation and Rural Development Studies 27 (2019): pp. 49–74.