Maxime Cunin of Superworld writes about designing infrastructure of and for sharing.

Prologue

In an era defined by continuous debates over transitions, energy infrastructure is often framed as a physical element in need of technical transformations. These transformations are largely assumed to be centrally driven by public institutions or private corporations. Conversations are usually crowded with engineers, economists, analysts, forecasters, and consultants debating the efficiency of—insert your favourite energy source here—technology. But, it must be said at this point: despite appearances, there is nothing more cultural than how we deal with infrastructure.

There is no denying that the way we heat and power our homes has seen some upgrades in the last couple of decades, viz. technical ones. More specifically, the range of options is expanding. That new technological reality, in turn, is opening up new modes of being for infrastructure, viz. cultural ones.

Given various converging advantages of using local resources—they are notoriously stable in price, arguably less damaging to the environment, and which feeling of safety is sharpened at times of geopolitical anxiety—groups of neighbours across Europe are coalescing to dream up and then set up their very own electrical and heating networks. Ironically, the shift from the distribution of a few massive elements—centrals, pipelines, pylons—to the agglomeration of many little things—pumps, panels, microgrids—brings the invisible infrastructure of energy into the tangible realm of the everyday. In this context of conceiving infrastructure as something other than centrally owned, who can claim to build energy infrastructure? With what purpose? And who gets to decide whether energy is shared, sold, or even gifted between neighbours?

Superworld.

Chronicles

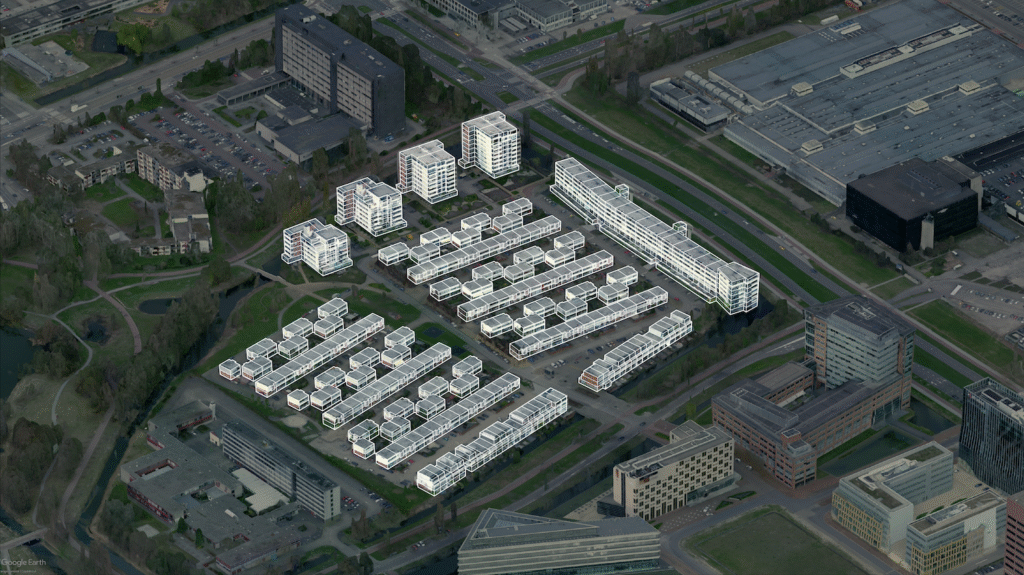

Park Haagseweg (PHW) is a small residential neighbourhood on the southwestern edge of Amsterdam. It is a far cry from the city’s popular postcard image. There are no historic houses, no canals, no boats. Instead, there are a couple of hundred monostylistic flat roof constructions built in the early 1990s, designed by the architectural firm Mecanoo.

The almost exclusively owner-occupied homes are evenly split between single-family row houses and higher apartment blocks. On the 90s’ advertising boards, the homes were proudly promoted as having perfect insulation and connection to the city’s natural gas network, as it was common then for new constructions.

Fast forward thirty years to 2019, the Climate Act becomes law in the Netherlands. It becomes official—the nationwide natural gas infrastructure is scheduled to retire by 2050. This high-level type of announcement, like the proverbial smoke-filled rooms, very concretely percolates into the everyday lives of most Dutch families: how will you even heat your home now, technically?

Further to the east, geopolitical instabilities emerging from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine pushed energy prices, natural gas included, to unbearable heights. For Dutch households, the ever-growing concern on everyone’s mind becomes: how will you even heat your home now, financially?

It is at that moment, at the crossroads of future anxieties and present concerns, that a handful of residents of PHW gather and wonder: wouldn’t we be better off, financially and environmentally, acting together? Could we imagine our own network—an energy system of, by, and for the neighbourhood?

And so started the PHW Power Coalition.

Designing purpose

In the summer of 2022, Thomas Krall and myself, architects-designers of Superworld, received a call from a local resident, Hans Roeland, a Dutchman in his mid-fifties active in Amsterdam’s energy transition scene. He asked us if we could help him and his neighbours in PHW to explore how they could take collective energy action. It was an intentionally open-ended proposition, possibly involving collective retrofit, producing and storing heat in the neighbourhood, as well as sharing electricity. The initiative’s unusually undefined starting point is due to a focus on collectivity rather on a particular technical outcome. It is a pursuit to find out what kind of infrastructure can support that focus.

This is precisely what appeals to the designer’s attitudes—open-ended questions comfortable with ambiguities, as the architect-turned-institutional-designer Marco Steinberg might put it—rather than the engineer’s expertise in focused optimisation of answers to a singular question. This doesn’t mean that engineering and financial considerations do not have their importance in the undertaking. The point is that it is firstly about designing a shared purpose and potential futures that all the residents would want to be part of.

A coalition of the willing

There are other energy communities around to be taken as an example, like the Schoonschip neighbourhood in Amsterdam, a cooperatively self-developed floating neighbourhood currently inhabited by 144 residents. Proudly claimed to be the most sustainable floating neighbourhood in Europe, the cluster of homes comes with its own private high-tech energy sharing network. Energy exchanges between houses are recorded by a blockchain-based local currency, hinting at a near future where this currency could give rise to a community time bank, or be traded for products in participating local shops.

It is a radical vision for domestic infrastructure, with a purpose well outside of the market economy. But at its core, its unspoken, yet unmissable foundation is that it is a newly built area, formed by an intentional community of like-minded individuals, deciding to live together.

The reality is quite different for a neighbourhood that has existed for over thirty years, like PHW. Here, residents are individuals with rather loose ties, who mostly did not intend to live together. There is no immediate obligation or even reason to cooperate, so part of the initiative is to create the desire to act as a collective. It is about gathering a coalition of the willing across ages, genders, party politics, social conditions, and values.

These pictures are the representation of PHW’s everyday as seen through the lens of Antoine Thevenet, urban designer and photographer. Tomorrow might look similar to today, while functioning very differently. This work is part of an ongoing conversation about representing intangible changes in the built environment.

Photos: Thevenet

Network of everyday salons

Our aim in PHW is firstly to cultivate trust between neighbours by gardening a fertile ground for conversations—a network of everyday salons. The format of these salons varies—there are framed presentations, neighbourhood assemblies, pop-in video calls, coffee table conversations, etc. Sometimes they are planned or formal, other times spontaneous or casual.

To anchor these discussions in the concrete, it is necessary to form and inform different potential futures, without intending to be precise, but rather directional, and let various enabling or constraining conditions that these futures entail to emerge. These moments are simultaneously propositional and receptive. Proposed futures inform conversations as much as the conversations inform future directions. This process has resulted in co-curated visions that sit at the intersection of culture and technology.

the energy coalition opportunities to the wider neighbourhood and hear residents’ suggestions, but also to bring neighbours together as a community.

Superworld.

Potential futures

The investigations are both inward-looking—weighing whether there is space for more solar panels, for instance, or any aquathermal and geothermal sources available—and outward-looking, towards the neighbourhood’s direct surroundings—checking whether the data centre across the road could provide residual heat, for instance. We look into what is already there as well as what is wished for.

Four coherent directions have emerged, with varying degrees of collectivity, agency, and ownership, bringing to the surface different shades of energy culture they might help to cultivate:

- All-Electric: everyone on their own. Residents are to reduce their energy demands within the limits of their own property.

- Collective Electricity Network: a shared electricity infrastructure, challenging the notion of property, as individual roofs are combined, covered by shared solar panels, and there will be an eventual neighbourhood battery.

- Collective Heat Network: pushing further, freeing up more options to enable energy sufficiency, with heat production from local resources, while demanding some insulation measures on the envelope of the houses.

- District Heating: switching from centrally delivered natural gas to centrally delivered heat. The exclusive heat provider, a for-profit private energy company, received a concession from the municipality for the next few decades that doesn’t allow for switching to a cheaper or greener competitor. However, this option trades community ownership and its not-for-profit values for lower insulation requirements in homes, as the heat comes at high temperatures and ensures comfort even in more leaky houses.

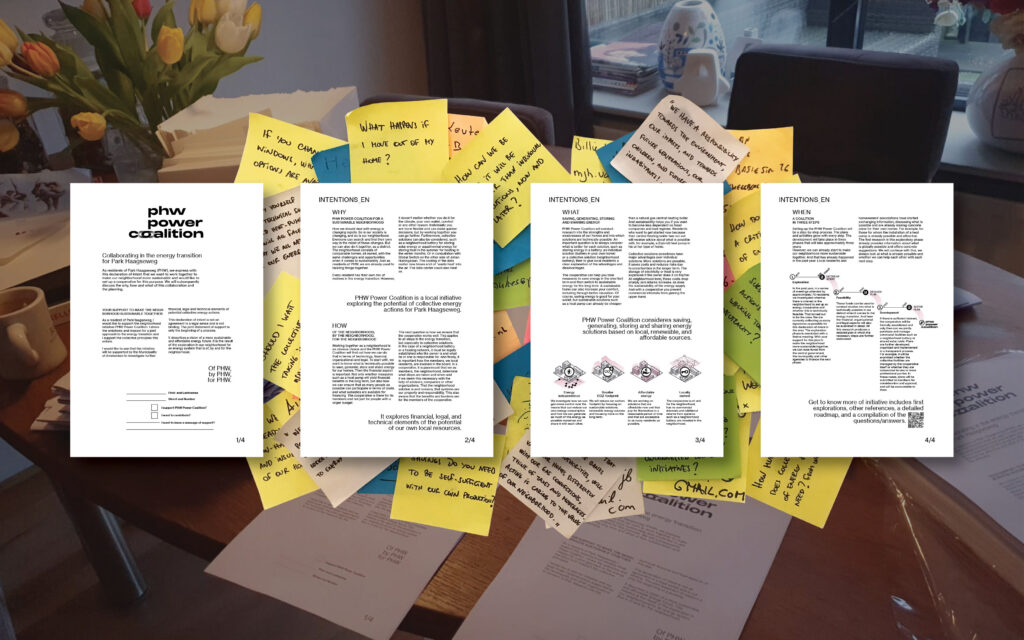

This is not a contract

In January 2024, this journey has taken its first big leap, becoming crystallised in a declaration of intent—a co-written collective covenant—weaving the neighbourhood’s ambitions into an open-ended mission. Rather than taking the shape of a contract—heavy, binding, prescriptive—it is a living document that asks for support and not commitment, a box to be checked rather than a document to sign. It is an invitation, not an obligation. At its core, the letter articulates the purpose of PHW’s own infrastructure—energy sufficiency, smaller carbon footprint, affordable energy, and local ownership, i.e., principles that are guiding the community as it navigates the complexities of the evolving process. So far, more than half of the neighbourhood has signed the covenant, manifesting loudly the desire for energy alternatives.

The notion that the state is providing services for its citizen clients, whichincludes a whole array of infrastructure, could just as well be amended to a more participative dynamic.

Materialising intents

The exploration is now heading towards the analysis of the socio-technical assemblages of each potential future. The moment has come to fill the room with the usual suspects—the engineers, economists, analysts, forecasters, and consultants. With a designed purpose, the technical and financial aspects of developing and managing the neighbours’ own energy system will be refined and specified.

This calls for formalising organisational intents—a modular entity that is able to expand or shrink in scope—as well as its practical aspects of governance—who can vote, when, how, with what metrics, and whether there even is a voting system. As the designer-urbanist Dan Hill put it in his book Dark Matter and Trojan Horses, it is about ‘the systemic redesign of cultures of decision-making at the individual and institutional levels’.

Meanwhile, in the shadow of their everyday lives, neighbours are extending their practice of coalition-building, spreading the word, and sharing information. The very cultural notion of sharing energy is materialising not only in the physical infrastructure to come, but also in the intensified relationships between neighbours.

Superworld.

Epilogue

This particular story is not about a retreat. It is not an off-grid pursuit of individuals withdrawing from the wider collective, but quite the contrary. For this group of neighbours, it is an effort to aggregate their limited individual capacities into a greater agency. This intermediary level of organisation of living together—more than a series of juxtaposed individualities, yet less than formally governed citizens—calls for a new balancing act between seemingly diverging forces: community networks vs. public infrastructure.

When examining such new forms of socio-technical assemblages, the French historian Fanny Lopez pleads for new definitions for responsibilities and scales of solidarity in the energy system. Perhaps in the new technological reality, the order of collective responsibilities is first to provide energy locally, and then only second to count on the large public infrastructure. For PHW, this means that they would be looking at sharing their energy on the neighbourhood territory, and only then compliment it with the sharing of energy on the national territory.

It is important to note that, while there are other related initiatives around, the community-led initiative of PHW remains an exception. This exceptionality is the result of many converging factors. In the words of a local resident, ‘most of us own our homes, a bunch of us are retired and have time, some of us have the knowledge’, all of which makes it easier to start. If one wanted to enable a future where citizen-led infrastructure multiplies, going from spontaneous and unique to fostered and plural, one would need to provide the necessary elements ensuring equity of access and opportunity.

At some dim level, this challenges the established definition of citizenship, and by extension that of government. The notion that the state is providing services for its citizen clients, which includes a whole array of infrastructure, could just as well be amended to a more participative dynamic. Groups of citizens can meaningfully contribute to a larger coordinated whole. They can extend established spatial infrastructure with more localised components, while infusing the overall system with more shades of values and purposes.

In this emerging citizen-government relationship, it remains to be explored what capacities the public sector would have to develop. It is necessary to define the required elements for supporting the creation and coordinating the operation of a network of community-owned energy infrastructure at scale, including its funding structure, regulatory context, ecology of enablers, and accounting system—in other words, to clarify the emerging role that governments ought to occupy, and formalise it to sustain the symbiotic relationship with the participating citizens.

In his 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith famously argued that competition between individuals produces prosperity within the community. Three centuries later, one can only wonder if it is instead through participation and cooperation that mutual thriving can be ensured.

MAXIME CUNIN is an architect and strategic designer. He prototypes collective forms of organisation in the built environment at Superworld, a practice he co-founded together with Thomas Krall.

HEADER photo by Antoine Thevenet

PUBLISHED: MAJA 3-2024 (117) with main topic INFRASTRUCTURE