The nostalgic image of an architecture office full of drawing boards and rapidographs is alien to the generation born after the restoration of Estonian independence. The children of the 1990s with access to computers probably grew up with MS Paint and MS Word font collection, kept replugging their landline to a dial-up modem to take their first steps on the Internet, and spent their evenings chatting with friends on MSN Messenger and listening to music on Winamp. We began our architecture studies by acquiring basic computer skills and then boldly plunged into the world of 2D and 3D, visualisation and BIM design. Today, it would be unthinkable to work as an architect relying solely on analogue technology. The hardware of our daily practice consists in a keyboard, mouse, and high-resolution monitor. Granted, there is still a roll of tracing paper for developing competition entry ideas stuffed away in a drawer, but its role in day-to-day work is rather marginal.

In addition to hardware, however, there is no getting around the importance of software. Knowledge and skilled use of the necessary software helps to create architecture as well as productise and present it. Given the increasing requirements of precision and speed in design, it is important to adopt digital products and technologies that support speeding up the work process and help to avoid errors. This is a continuous learning process, for in the so-called digital arms race, many software developers keep upgrading their products to make them more powerful and convenient. It is imperative in architecture to take advantage of that technology, e.g., by automatising routine processes so that the architect would have more time for more meaningful professional activities. Meaningful activities do not include formatting the drawings, tweaking line thicknesses or choosing the right filename for the National Register of Buildings, but rather creating some forward-looking spatial design, and defining and communicating the changing needs of users. As well as sustaining the environment, of course. Optimising the internal processes, administering the right hardware, and choosing the best software tool are non-negotiable aspects of the architects’ daily creative process. All this constitutes infrastructure for us as architects, which can be either a slow and winding gravel road or a motorway to quick and high-quality results. The process of creating architecture requires skilful combination of both speeds.

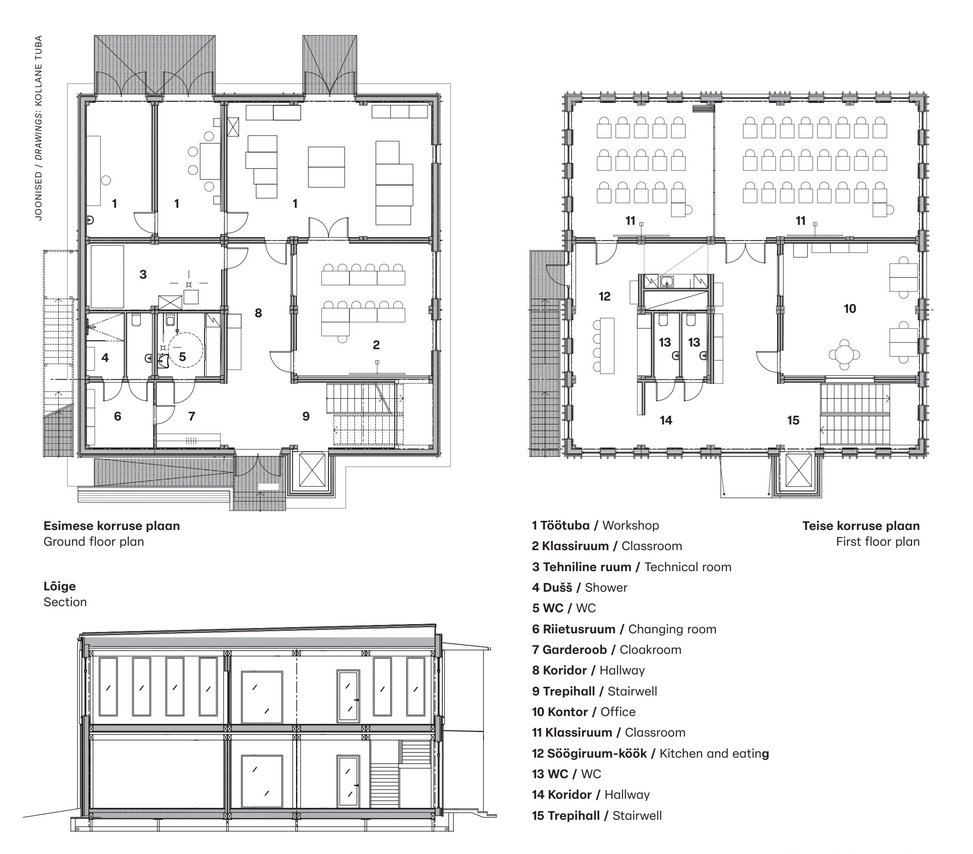

ELEKTRILEVI TRAINING CENTRE

Location: Kiili, Eesti

Gross internal area: 415 m2

Head of Development: Renee Puusepp, EKA PAKK (Estonian Academy of Arts Timber Architecture Research Centre)

Architecture: NOMAD, What If, Kollane tuba

Interior architecture: Verde

Structural Engineer: CAD Projekt

Contractor and fabricator: Estnor

Client: Elektrilevi

From project to building: 2022-2023

Photos: NOMAD

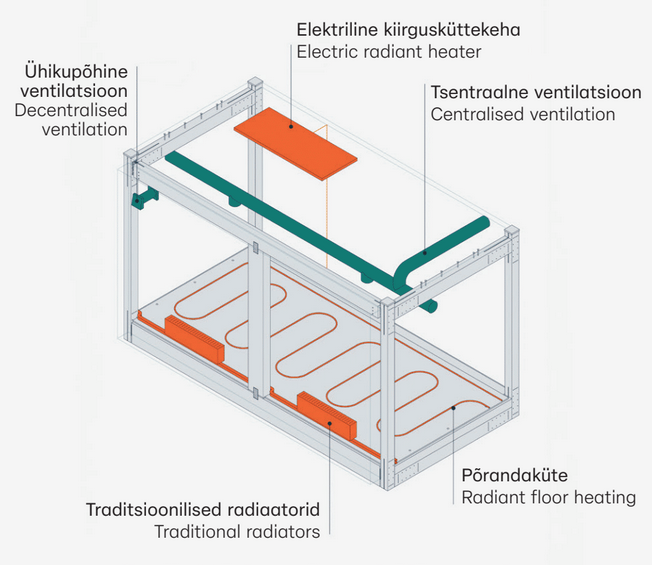

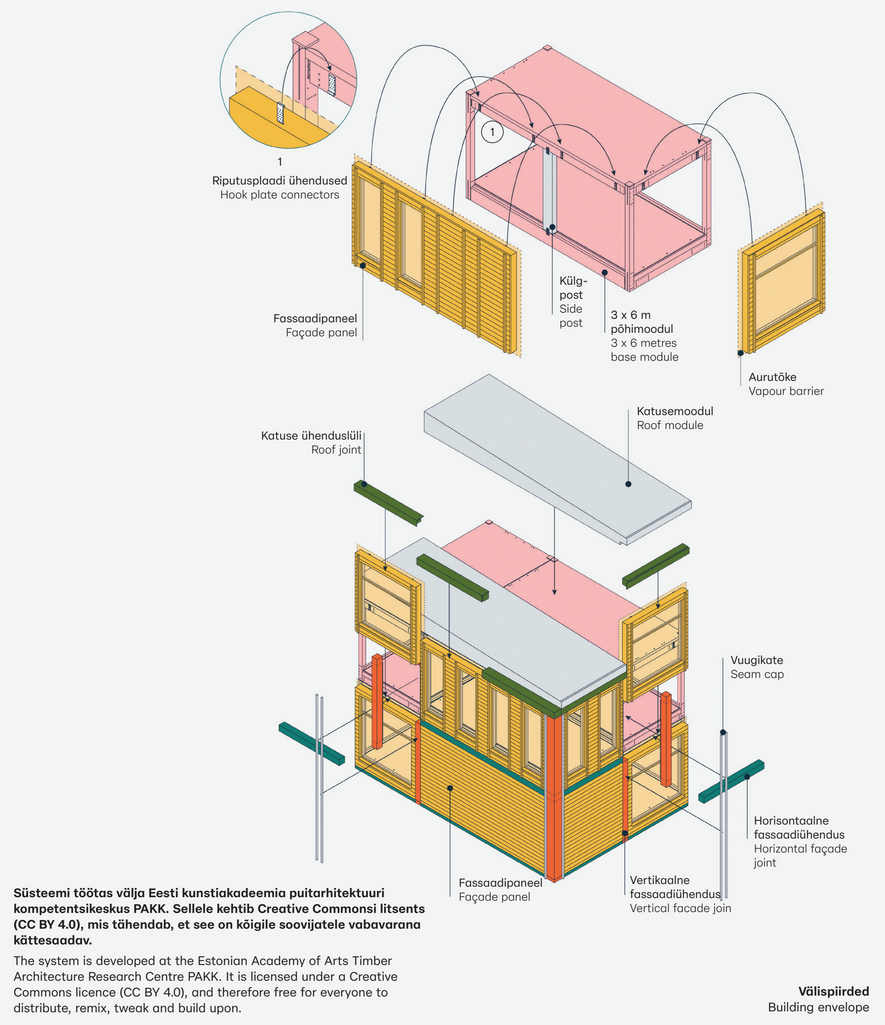

Pattern Building

Over several years, the Estonian Academy of Arts has been developing systems thinking in the form of 369 Pattern Building design system. Pattern Buildings are one more way to package1 architecture as a product. Having resulted from research by architects, representatives of an environmentally conscious profession, one aim of Pattern Buildings is to be environmentally sustainable—the buildings enable a more circular use, meaning that they can be disassembled, moved, reassembled. They are prefabricated in factory, which is already in essence more sustainable—factory production is fast, automatised, and low in waste. A Pattern Building enables to customise the product to the needs of the client—one can toy around with stair shapes, façade solutions, and the layout of room modules. One particularly attractive feature is the promise of keeping construction costs under control and being able to immediately calculate the carbon footprint of the building.

Elektrilevi2 Training Centre in Kiili, completed in 2023, is an outcome of this research. The building itself is perhaps not as architecturally thrilling, but nevertheless an important one to focus on, for it is a meeting point and materialisation of certain earlier forward-looking decisions—the decision to commit to a long-term study of a certain type of construction technology to offer ready-made solutions, the decision to look into public-private partnerships, and the decision of a publicly traded company to move toward an innovative and sustainable value proposition.

The training centre, built by OÜ Estnor, applied the systematic principles of mass timber construction that were established in the research. The result is a building with a 500 m2 gross area, meaning that the price per square metre (outdoor areas and technology included) is approximately €3200 + VAT. Seen flatly from the perspective of construction costs, this might seem a bit expensive. But looking at the whole process from the perspective of research and innovation, the picture begins to look different. In a world of startups filled with hot air and other sorts of fiddlers, an investment of less than two million euros has produced a sample product whose broader value consists namely in the research, technological development, and innovation involved. The achievement is technological precisely because Pattern Building is not merely a physical building—regardless of the confusing semiotic association—but a piece of functional open-source code or technology for building design.

Pattern Building as software3

The current research narrative should perhaps be clarified so that instead of talking about building we talked more about development work, systems thinking, which gives an input to technological progress and from thereon to software. Users of the created software are architects and manufacturers, and the output is architecture. We should not emphasise the end product, for without the preceding process, the building would not exist in this form. Instead, we should talk about the infrastructure of the future, software-based smart solutions for architects and timber building producers that make the lives of designers and architects easier and faster. Whether it would be a separate app, plugin or website, is not really important, for development is, as always, open-ended.

The centre at Kiili is an excellent example of a pilot project that combines future mega-trends and has created a digital product that is based on experience and knowledge. The digital product was used to create a building that is environment-friendly, innovative in its approach, and features automated processes on every level. According to project participants, completing this pilot building contributed significant improvements to the existing ‘principles’ of the system. In order to develop the incipient software further, there need to be further test projects.

Architects’ role in a changing technological context

I can see that this sort of technological development might also raise some questions and cause some fear in the field. In my view, as long as people continue to have complex inner worlds and idiosyncratic personal preferences, the important role of architects as steerers of spatial decisions remains. In order to steer, it is important to know one’s client very well. I cannot see that this work could be taken up by an artificial intelligence that cannot answer questions about to whom and why some product or service is necessary, does not offer novel solutions, and does not innovate by itself. The necessary impetus, after all, comes from a combination of creativity and problem analysis, which enables one to ask the right questions. Architects still have the opportunity to realise their full potential. There are innumerable new solutions on the market for visualising one’s ideas. Pattern Building is merely one of many, but if we allow ourselves to think big for a moment, perhaps this could even be the sought-after digital tiger, given that the construction sector accounts for 30–40% of global CO2 emissions and is to an exceptionally large extent unchanging. One only needs to dig up some joy of discovery and learning in oneself to go along with this global trend and take pleasure in supportive technology.

Photo: Sven-Olof England

Conversation with the Estonian Academy of Arts Faculty of Architecture senior researcher Renee Puusepp

The role of the Estonian Academy of Arts, conductor of research, is also that of a mediator, guiding the students as an academic institution and helping to bring the developed system to young architects. The Academy also acts as a mediator for private companies who can turn to it when they wish to innovate. In 2019, the Academy began researching prefabricated timber buildings. The research was based on the 3-6-9 system, where the three numbers mark possible spans. Now the system has been simplified down to three- and six-metre modules, as the constructional techniques required for nine-metre modules reduced the efficiency of the system.

In this particular project, the building was created using digital modular construction software. The modular house is built with selected components that enable variations in rooms and ensure efficient use of building materials. The online interface for visualising the principles of modular building design is a spin-off from the research that continues to be developed under the name of Creatomus Solutions. Keeping the software online is a strategic decision that makes the digital tool easily accessible. The local industry has not yet widely adopted the system; rather, it has been applied abroad. However, Renee sees great potential for local timber building manufacturers who could consider using the technology to automatise their design process and collaborate efficiently with architects.

Conversation with Elektrilevi Board Member Rasmus Armas

Elektrilevi’s previous training centre on Kadaka Road in Tallinn was obsolete. The sheet metal building that lacked acoustic insulation was detrimental to day-to-day training of specialists who take care of our common infrastructure. Before launching the process to design a new training centre, the company came up with a vision that focused on sustainability and long-term view. The company also acknowledged that a regular procurement process would lead to a ‘regular’ building that would not fulfil the expectations of green innovation. Thus, a decision was made to contact the Estonian Academy of Arts, who offered a modular timber building system that had been developed over years of research and aligned with the company’s aims. The use of timber was not a goal of its own, but fit very well with the recommendation by the Elektrilevi board to seek solutions for the new building from collaborating with R&D. The Estonian Academy of Arts as a university played the role of pushing for innovation.

The conception of Pattern Building fit exceptionally well with the needs of Elektrilevi, as the company is keeping up with the times as an employer and wishes to offer flexible working conditions regardless of location. The constructional principle of Pattern Building that allows to disassemble it and expand or shrink it when needed resonated with this very well indeed. Thus, should the company wish to make changes in the volume of office spaces, this system theoretically offers the flexibility for doing so.

In discussing the budget, it became clear that although the price per square metre in the procurement is high for an office building, the amount spent on the whole project did not exceed the overall sum designated for it. In the big picture, the company managed to stay within the planned budget, which is of great importance to every company. The company also understands that should it decide to take up another process of building a modular building, the risks of a pilot project have now been mitigated and the construction price would thus be lower.

In Rasmus’ view, the greatest value of the building is that it enables to train a large number of electricians in new, comfortable, light-filled premises. The company clearly acknowledges that a good work environment can increase motivation and is satisfied that the chosen path has fully paid off.

ANNIKA VALKNA is an architect whose creative endeavours are divided between the broader issues of urban planning and the more intimate scale of residential buildings. She is also studying for a master’s degree in landscape architecture.

HEADER photo by Sven-Olof England

PUBLISHED: MAJA 3-2023 (117) with main topic INFRASTRUCTURE

1 The Estonian verb ‘pakkima’ alludes to PAKK, the Estonian acronym for the Timber Architecture Research Centre at the Academy—Ed.

2 The main electricity network operator in Estonia—Trans.

3 ‘Software’ is probably not be the correct term in the view of IT specialists, but for the non- specialists, this is the term that best explains what we are discussing here—a computer programme for modelling that helps to create architecture.