Paula Veidenbauma and Diāna Mikāne ask: how to talk about a railway that currently exists only in our imagination, but is nonetheless very present in our daily lives?

Vignette. The Titanic is going down! My heart will go on

On 11 July 2022, representatives of Eiropas Dzelceļa Līnijas, the body that is implementing Rail Baltica (RB) in Latvia, met with journalists in front of Riga’s legendary car park, hair salon, and shopping centre Titāniks [‘Titanic’]. The building was set to be demolished that day to make room for the new railway station landscape. Located right in front of the Riga International Coach Terminal, it had been designed in 1999 by architects Ludvigs Saprovskis, Berenika Austriņa, and Artis Zvirgzdiņš. With a signature ship-like façade highlighted in red, the building was a monument to 1990s turbo-capitalism mixed with early 2000s optimism, bearing the name of a 1997 hit movie.

Commenting on the demolition of Titāniks, Kaspars Vingris, chairperson of Eiropas Dzelceļa Līnijas, expressed little sentiment regarding local postmodern architecture: ‘Fortunately, we did not find any cultural or historical value here’.1 As shown in the news story, on the first day of demolition, the workers played Celine Dion’s ‘My Heart Will Go On’ on the speakers, turning the bulldozing into a dramatic performance for everyone passing by.

The ‘Titanic’ of Riga disappeared in two months’ time. As witnesses to this event, we found ourselves wondering how to think of such ephemerality. The loss of Titāniks marked the beginning of a new era—an era where the RB narrative started to unfold and manifest around Riga in materialities, or rather in their absence.

for passengers. With the windows opening towards the construction of the new station, fiberglass chairs designed by Grīnvalds/Bērziņš creative duo are still waiting.

Photo: Gustavs Grasis

Artistic network

In autumn 2023, we initiated Baltic Lines—an artistic network connecting eleven artist-researchers (Sofie Lucia Maria Carlson, Aistė Gaidilionytė, Danute Līva, Diāna Mikāne, Katariin Mudist, Gustavs Grasis, Valtteri Alanen, Eglė Šimėnaitė, Kamilė Vasiliauskaitė, Mattias Malk, and Paula Veidenbauma) from Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Finland, and Sweden—to create a space for reflecting on various lost Titanics, and the Baltics as a corridor of potentials. We approach RB as a lens to investigate the inclusion of the Baltic states in the context of Northern Europe and situate the network as a critical urbanism practice using means of artistic research to delve into the socio-cultural, historical, and geopolitical dimensions of RB.

Although Baltic friendship has proven difficult to maintain while developing the railway (RB does not even have the same name across the countries—in Estonia, it is called Rail Baltic, while in Latvia and Lithuania, it is implemented as Rail Baltica), we ended up creating a friendship group ourselves. We have been researching, going back and forth between Riga and Valga, going to offices full of optimism while hearing news about inevitable bankruptcy, and stepping onto bridges of promise while encountering bridges to nowhere. What follows is a reflection on the group’s journey so far on tracks parallel to RB, offering some anecdotal evidence, shared experiences, thoughts, bits of conversations, and insights from a welcoming summer residency, as well as outlining the project’s interdisciplinary approaches, research practices, and adapted methodologies.

We’ll stay forever this way,

You are safe in my heart and

My heart will go on and on.

A view of the Titāniks in the centre of Riga as seen from the Riga International Bus Terminal. The building was demolished in 2022 to construction workers playing Céline Dion’s ‘My Heart Will Go On’ in the background.

Photo: Girts Ozolinš

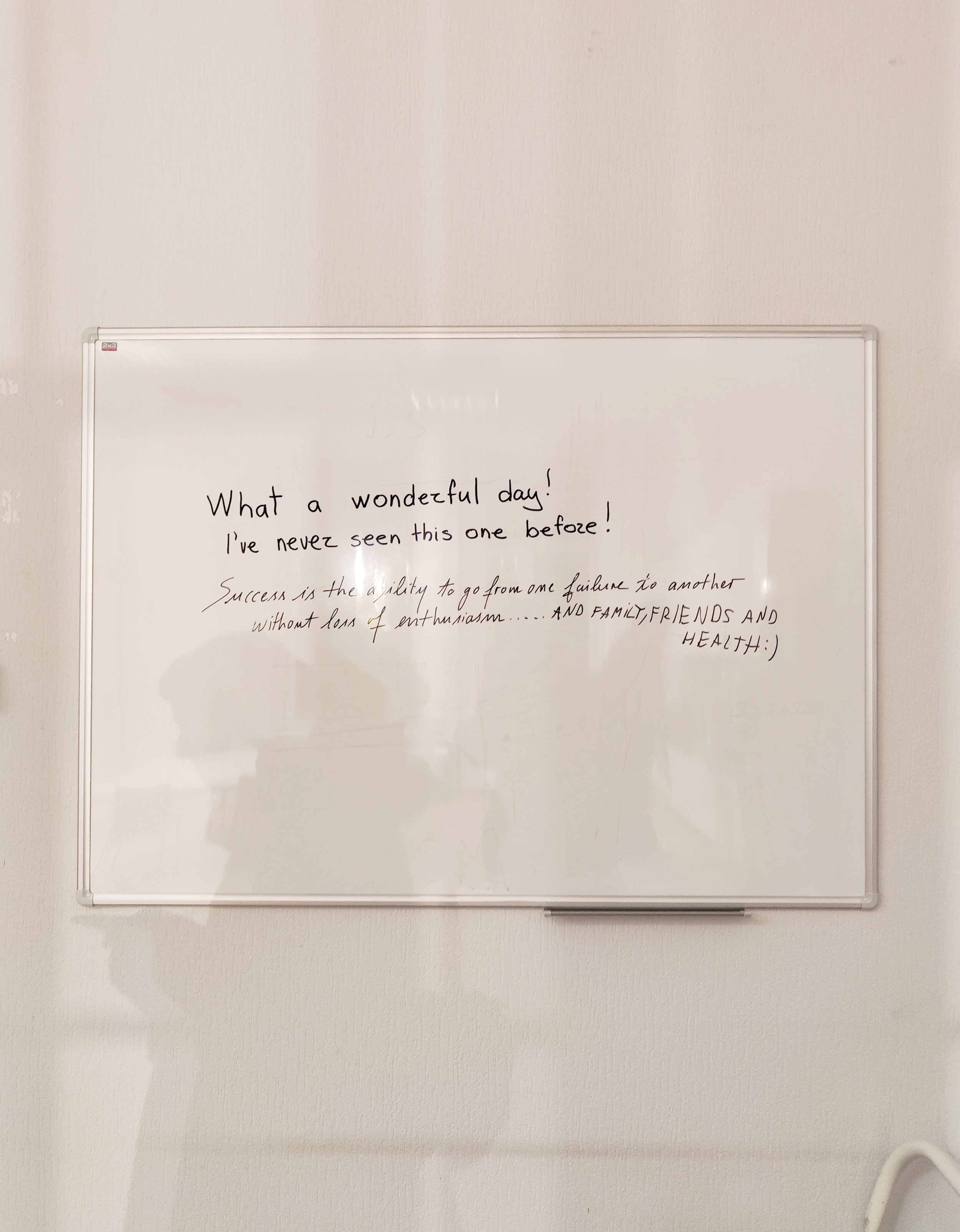

‘Success is the ability to go from one failure to another without loss of enthusiasm.’

Inspirational quote from the whiteboard in the Riga office of Eiropas Dzelceļa Līnijas

RB has been an abstract concept for some time. Although its origins date back to 2001, when all three Baltic transport ministers signed the cooperation agreement to proceed with the project,2 it now seems that the opening date of the new train line connecting Tallinn to Warsaw might be delayed until after 2030.3 Reorienting the Baltic region towards the West has been a long-standing goal that underlined the states’ entry into the EU and NATO (2004), introduction of the border-free Schengen Area (2007), and joining the Eurozone (2011–2015). In 2017, the UN officially announced that the three Baltic countries are now classified as Northern European.4

Through the thick and thin of labyrinthine post-Soviet diplomacy, the Baltic states have proven themselves a geopolitical alliance grounded in friendship and shared history. We have been holding hands since 1989. The train connection developed side by side with the region’s continuous rebranding thus becomes highly symbolic. As political scientist Carole Grimauld says in the documentary Rail Baltica—Ein Zug für Europa (2024), the train line becomes a metaphorical device: ‘This symbol [RB] means turning away from the Soviet and Russian past’.5

Photo: Galimai.Store

However, exploring these close ties of the Baltic friendship through the lens of railway infrastructure reveals a field of relational fluctuations. Pier Vittorio Aureli in his book Abstraction and Architecture (2023) argues that architectural practice in the West has followed a trajectory leading away from the ‘plan’ towards the ‘project’, transcending from manuals to managerial structures. There seems to be a clear tension between the project, in the sense of organisational capacity, and the plan, in the sense of structural knowledge. As the implementation of RB depends on a strong and cohesive singular project vision across all three Baltic countries, it is undermined by their differing agendas. Baiba Rubesa, long-time CEO of RB who resigned in 2018, has commented that Rail Baltic(a) is the ‘saddest example of mismanagement in the history of public sector governance’.6

In the winter of 2023, all Baltic Lines participants gathered in Riga to share regional perspectives and subjective takes on the development and perception of both RB and the collective’s collaboration. On 1 February, we had a meeting at the Riga City Architect’s Office. The stance of the Office on the RB project was vehement: ‘If we don’t manage to build it, then the Baltics might become a recreational area’. The project is further underscored by defence-related considerations, particularly in light of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, and the need to strengthen connections with the European Union through enhanced logistic infrastructure and new travel arteries. The takeaway from our get-together was quite straightforward—the railway must be built, with or without a detailed plan, support, and vision. In case the project fails to be implemented, the future that awaits us is of a ‘land in-between’—a forest or a theme park.

Photo: Sofie Lucia Maria Carlson

Artistic research examined

Upon arriving in Valga for our residency, we read that the ‘Titanic’ was not the only one sinking. Eiropas Dzelzceļa Līnijas might need to apply for bankruptcy.7

Notes from the field. VARES, Valga. 5 June, 2024

In June 2024, our Baltic Lines team gathered at the VARES residency in Valga to catch up on each participant’s research and artistic ideas as well as to synchronise them with the group’s efforts. There we also discussed the methodologies of the Baltic Lines project. We reflected on what ‘artistic research’ means in this context, acknowledging that it is also a buzzword of sorts, often meant to legitimise artists as creators of knowledge in an academic environment. Grounded in the notion of not-yet-knowing, the idea of artistic research is going through a web of definitions, both towards greater self-awareness and incorporation into academia.8 The Vienna Declaration on Artistic Research defines it as ‘practice-based, practice-led research in the arts which has developed rapidly in the last twenty years globally’.9 Or, in the words of researcher Ana Hoffner: ‘But if artistic research is supposed to also question the notion of research itself, then its larger intervention must be into the questions: “What is the experiment? What is the laboratory?”’.

What kind of knowledge are we going to produce? Is it legitimate? People might ask us: ‘So, are you for or against the train? What is your position?’. What will we answer? Should we establish a common ground and find a unified position, whether it be actively political or more subtly conveyed under the guise of ‘It’s art’?

We meet an older woman on the streets of the small town of Valka, close to the border with Estonia. We talk about Rail Baltica and she says: ‘If it will ever be finished, it will not be my train’.

Notes from the field. VARES, Valga. 7 June 2024

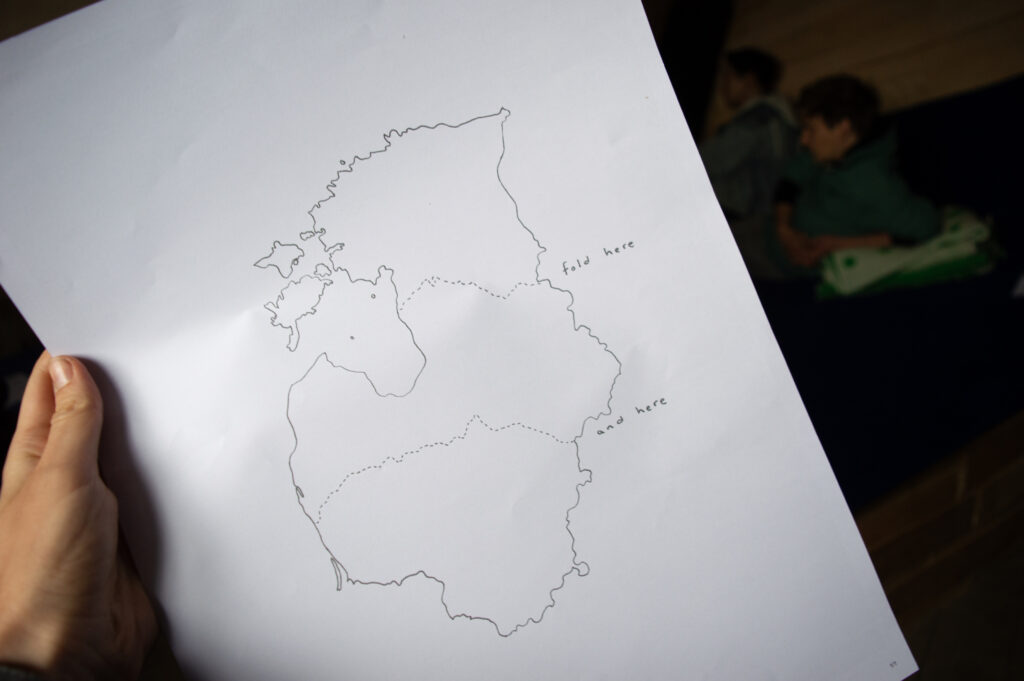

Given that we were looking into a multilayered megaproject with complex planning and implementation, we pondered how to avoid erasing its chaotic shapes and changing boundaries. In one of our conversations, our group member Gustavs Grasis suggested that perhaps our approach could be called ‘spinning off’, meaning that we are not engaging with arguments for and against building, but rather viewing the rail line as a symbolic element of space-time contractions in our shared world of the Baltic economic corridor. The rail line connects different temporalities and exists through narratives, thus leading us away from the actual material railways, just like it is taking us away from the uncomfortable Soviet past.

Photos: Baltic Lines

Spinning off

The spin-off-related vocabulary that we find fitting to describe our practice is an attempt to define what the artistic research terminology and tools mean for our group, which functions on the outskirts of academia. We align with the idea that an ‘art practice can simultaneously constitute the subject, means, and medium of research’.10 And while spinning off, we are eager to question the existing hierarchy between disciplines and constructed ladders of knowledge quality, whether in scientific, artistic, or other forms. In the words of Donna Haraway, we are trying to bring particular perspectives into one space and translate them into ‘situated knowledge’11 by using practices such as sharing experiences, telling and collecting stories, creating fiction, exploring sites, conversing, etc. as relevant sources of knowledge.

We are spinning off in multiple directions. To give some examples, the artist duo of Eglė Šimėnaitė and Valtteri Alanen is looking into the Helsinki–Tallinn underwater tunnel as a contemporary equivalent to mythological thought echoed in underwater beings;Vilnius-based architects Kamilė Vasiliauskaitė and Aistė Gaidilionytė are looking into the overlapping paradoxes of care and neglect, locality and renovation, reuse and value in the railway district of Naujininkai (Lithuanian for ‘the new world’) in Vilnius; Sofie Lucia Maria Carlson, an artist working between Stockholm and Helsinki, is looking at the construction of RB as if it were a gigantic version of the parlor game known as the Exquisite Corpse.

Photo: Sofie Lucia Maria Carlson

Spinning in Baltic-Nordic friendships

When one follows the Druzhba, one finds oneself in Druzhba, at Druzhba, meeting Druzhba.

‘A few years after finishing school, I started to miss the feeling of checking in with a classmate at their desk, sharing what we were up to in the hours outside of class. These felt like the moments where I learned the most,’ writes Sean Yendrys in his letter for the Dear Friend catalogue.12 In the letter, Yendrys advocates for hanging out as a method of informal learning, which he has also been trying to incorporate into the graphic design MA programme since becoming its director. It is an idea he had also encountered at Documenta 15 in Kassel, where the curators used the Indonesian term ‘nongkrong’, meaning being around each other whilst chatting and spending time together.13 So, in order to spin off, there needs to be space for spinning around—time and space to meet, share, and talk, i.e., perform a sincere friendship. There is a curious parallel with the forced friendship of the Baltic countries in implementing the RB project—forced in the sense that not being friends is not an option, at least not on paper, when the funding is dedicated to creating new geopolitical friendships. The Baltic Lines project is mainly funded by the Nordic Culture Point, and our friend group too was set around the Baltic-Nordic grant collaboration guidelines. Perhaps our artistic research then cannot only be about spinning off, it is also about spinning around our shared corridor. What if hanging out, spinning around, was the practice?

PS. Dear reader, in the meantime, we invite you to hang out with us from 12 to 27 October at InTheCloset Gallery in Vilnius, and spin with and around our friendship projects. Who knows, maybe we will spin and spin until we become friends. Best friends. <3

(the edition was published in the fall of 2024–ed.)

PAULA VEIDENBAUMA is a spatial practitioner whose encounters encompass art, architecture, urbanism, and theatre. Together with Diāna Mikāne she operates as gel office.

DIĀNA MIKĀNE mingles at the intersections of curatorial, research, and art practices. Together with Paula Veidenbauma she operates as gel office.

HEADER: the new Rail Baltica Riga Central Station takes shape in the background of the existing station. Photo by Gustavs Grasis

PUBLISHED: MAJA 3-2024 (117) with main topic INFRASTRUCTURE

1 Katrīna Karzubova, ‘Ar humoru viss kārtībā’, TV3 ziņas, 11 July 2022.

2 Rail Baltica, ‘Historical Facts’, https://www. railbaltica.org/about-rail-baltica/history/.

3 Madis Hindre, ‘Train travel to Berlin moves into distant future’, ERR, 5 October 2022.

4 ‘UN classifies Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia as Northern Europe’, Kyiv Post, 7 January 2017.

5 ‘Rail Baltic – Ein Zug für Europa’, ARTE, 2024.

6 Dario Cavegn, ‘Rubesa slams Baltic governments, sees no chance of success without reforms’, ERR, 27 September 2018.

7 ‘Rail Baltica ieviesējam Latvijā var nākties pieteikt maksātnespēju’, Delfi, 2 June 2024.

8 Philippine Hoegen, ed., In these circumstances: On collaboration, performativity, self- organisation and transdiciplinarity in research- based practices (Onomatopee 181, 2022), p. 245.

9 ELIA, ‘The Vienna Declaration for Artistic Research’ (2022), p. 1.

10 Ádám Albert, Eszter Lázár, Dániel Máté, and Edina Nagy, eds., Approximating Borders Artistic Research in Practice (Hungarian Univerity of Fine Arts, 2023), p. 21.

11 Donna Haraway, ‘Situated Knowledges:

The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (Autumn, 1988), pp. 575–99.

12 A‘snail mail’ letter writing initiative (2019–2022) started by Sandra Nuut and Ott Kagovere at the Estonian Academy of Arts. Letters were compiled in a book published by Lugemik (2022).

13 Documenta 15, ‘Glossary’, https:// documenta-fifteen.de/en/glossary/.