Fossil fuels have arguably made the world a better place, allowing for the comfort, sanitation, and stability that transformed daily life for many people. Indoor spaces are now brighter, warmer, and more liveable, even in the harshest northern climates.

Heating and cooling make up half of the EU’s energy consumption, with 75% of this energy being sourced from fossil fuels, and as we know, 40% of global greenhouse gas emissions come from buildings.1 The cultural shift towards using materials and energy that are contained within planetary boundaries requires a reconsideration of the most fundamental assumptions about how buildings interact with the world.

The glass wall or ‘pan de verre’, as conceptualised by Le Corbusier, is perhaps the hallmark of modernist architecture, offering visual transparency and openness between interior and exterior, blurring their boundary. Fossil fuels enabled a voyeuristic viewpoint to natural processes, granting the privilege of close and seemingly immersive observation of the outside world yet with a reserved detachment. The outside world’s naturally occurring flux and imbalances of temperature, humidity, and microbes were to be kept out and absolutely not negotiated with but rather neutralised with the help of fuel-guzzling HVAC and a sealed interior. This ideal has been so seductive and sticky that even today, as one tries to create human habitats that respect planetary boundaries, it is hard to see how the abundant fuel of the recent past has perpetuated questionable points of departure with regard to what this kind of architecture could even mean.

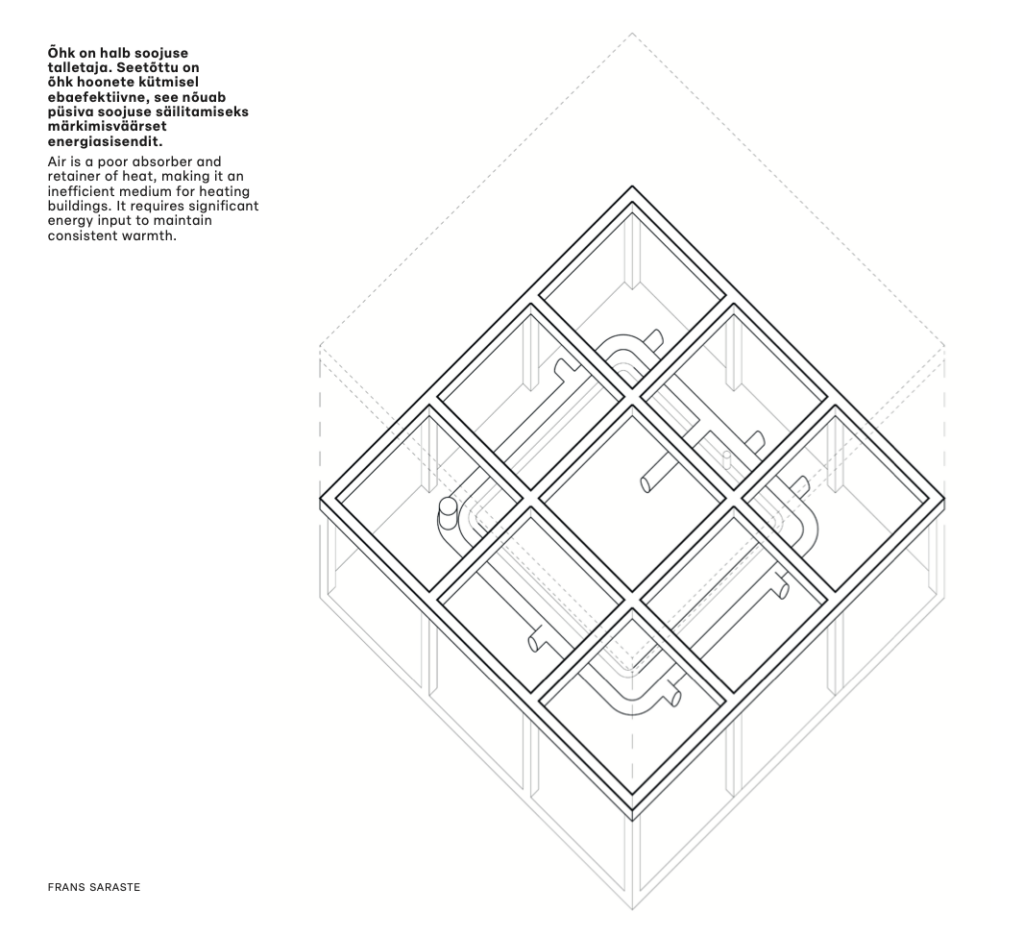

Buildings from the last 50 years represent a full-scale urban display of the inevitable failures to shepherd disobedient natural forces. The inherited sense of fuel abundance continues to inform how our relationship with the rest of the natural world is conceptualised. This is revealed particularly poignantly in the case of air—in the ways in which it is heated, enclosed, moved, and filtered. If one considers how air is currently used as a material in architecture, quite a few contradictions emerge.

Today, insulation practices still reflect the shift that spread in the 1960s, when the rise of prefabrication methods redefined exterior walls, reducing their structural role and prioritising their role as insulators. The premise for using insulation is grounded in air being a good insulator—which it definitely is. Thermal energy transfer relies on contact between molecules, but in air, the molecules are far apart. For heat to move through air, energy must pass from one molecule to another through a sequence of these rare collisions. This is why air is a good thermal insulator and why building frames are filled up with airy materials that slow the heat transfer from the comfortable inside to the cold outside. This airy material is then sealed off to prevent moisture from entering, an antithesis to the old brick and mortar or timber wall structures that absorb and store both heat and humidity.

Cheap fuel has accustomed us to a steady and unchanged room temperature by way of the thermodynamically impressive feat of warming and cooling air. Given that air is a poor medium for transferring heat, we might ask the following completely reasonable, but still all too uncommon question: why do we heat and cool buildings with air?2

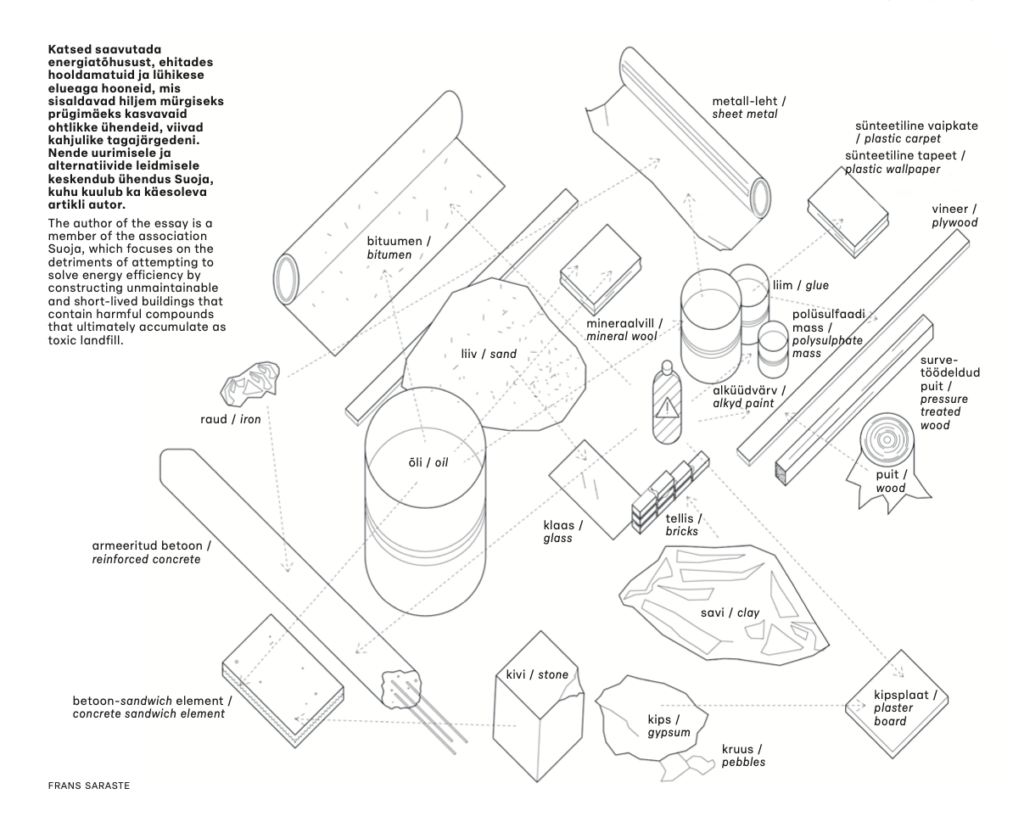

To sustain oxygen and humidity levels in the sealed and warm interior, we force in fresh air from the outside. This microbially rich outside air is sanitised by filtration systems equipped with biocides to prevent unwanted mould occurrences in the closed air systems. Despite unwavering yet costly attempts to separate ourselves from the outside world this way, there are constant reports about mould occurring in newly built energy-efficient homes.3 Modern energy standards that push for airtight, well-insulated buildings and limit air exchange with the outdoors have been found to cause moisture loads that often cannot be adequately dissipated.4 Microbiologist and emerita professor Mirja Salkinoja-Salonen has long questioned the basic premises of sealed structures—premises not grounded in science since thermal expansion alone causes failures in composite structures as materials expand to varying degrees. Nature keeps finding its way into these sealed constructions.

Worse yet, the combination of biocides used for filtering the air, chemicals injected into the construction materials, and cleaning products kill off many harmless microbes, making it easier for the most toxic microbes to thrive freely. Biocides and toxins are then drawn into the air from the structures and circulated by the powerful forced-air system. The formula leads to the sadly over-played punchline of Finland having the freshest outdoor air and the most indoor air problems.5, 6, 7

Impermeable only in theory, the insulating layers of buildings have come to be well understood as anything but permanent, rather highly replaceable, as something that will inevitably be given a more permanent role only as a landfill. Many materials used to enclose tiny bubbles of air contain toxic and non-biodegradable compounds that have no obvious place in natural cycles.8 Mechanical ventilation, insulation’s closed-system counterpart, is also considered highly replaceable, with 25 years considered a normal lifespan.9 This is no minor problem.

It turns out that the word ‘insulation’ lends itself as the perfect metaphor for the modernist tendencies to seal oneself off from the natural world, an idea that is captured in Kiel Moe’s book Insulating Modernism: Isolated and Non-Isolated Thermodynamics in Architecture. ‘To insulate is to isolate’, and to focus on ‘energy efficiency’ as the primary measure of a building’s energy use is to systematically isolate it as an object of observation, conveniently sealing it off from all the energy-intensive processes required to build it, sustain it, and replace it, not to mention the other forms of heat transfer of materials that are ignored in these steady-state U-value calculations.10

Buildings conceived before fossil fuels still tend to outperform buildings of the more recent decades, not only in being highly maintainable and resilient to their surroundings and their occupants but also in their use of operational energy.11 They are the examples that should inform future building. Yet, many recent advances in radiant heating and buoyancy ventilation prove that a shift away from our current practices in architecture does not have to entirely imitate the architecture of the pre-fossil fuel past, but rather expand on these proven principles.12, 13 There is a future for an architecture where the envelope absorbs and radiates heat while negotiating the humidity and microbial flora outside—an architecture that aims for a less forceful control over air.

FRANS SARASTE is an architect and educator. His upcoming doctoral dissertation examines how changing fuel paradigms have affected heating practices in Finland.

HEADER: A worker is finishing off the surface of an element of a construction product. Unknown photographer, 1965 (right). Forssa Museum

PUBLISHED: 4-2024 (118) with main topic AIR

1 European Commission, ‘Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the Regions: An EU Strategy on Heating and Cooling’ (2016)

2 European Commission, ‘Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the Regions: An EU Strategy on Heating and Cooling’ (2016)

3 See, e.g., Arianna Brambilla and Alberto Sangiorgio, ‘Mould Growth in Energy Efficient Buildings: Causes, Health Implications and Strategies to Mitigate the Risk’, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 132 (October 2020): 110093

4 See, e.g., Arianna Brambilla and Alberto Sangiorgio, ‘Mould Growth in Energy Efficient Buildings: Causes, Health Implications and Strategies to Mitigate the Risk’, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 132 (October 2020): 110093

5 Mirja Salkinoja-Salonen, ‘Viides Epidemia – Onko Siihen Lääkettä?’, presentation at Pikku parlamentti, 2 November 2016

6 Mirja Salkinoja-Salonen, ‘Sairaan talon ruumiin avauksia’, presentation at Rakenusperintö SAFA, 2015

7 Eeva Törmänen, ‘Professorin Neuvo Sisäilman Parantamiseksi: Avaa Ikkuna’, Tekniikka&Talous, 4 March 2015

8 Jonas Löfroos, ‘Runkotason Kysymys’, Suoja ry, http://www.suoja-ry.fi/runkotaso.html.

9 In Finland, the average lifespan of ventilation systems and heating radiators is estimated to be 15–25 years. Janne Laksola, ‘Tiedätkö missä kunnossa taloyhtiösi ilmanvaihto on?’, Kiinteistöliitto Uusimaa blog, 22 May 2023, https://www.ukl.fi/tiedatko-missa-kunnossa-taloyhtiosi-ilmanvaihto-on/

10 Kiel Moe, Insulating Modernism: Isolated and Non-Isolated Thermodynamics in Architecture (Birkhäuser, 2014)

11 Ransu Helenius, ‘Energiatehokkuus =/= Ekologisuus’, Suoja ry, http://www.suoja-ry.fi/energiatehokkuus.html

12 Salmaan Craig et al., ‘The Design of Mass Timber Panels as Heat-Exchangers (Dynamic Insulation)’, Frontiers in Built Environment 6 (6 January 2021): 606258

13 Eric Teitelbaum and Forrest Meggers, ‘Rethinking Radiant Comfort’, in Routledge Handbook of Resilient Thermal Comfort (Routledge, 2022)