VERTIKAL NYDALEN

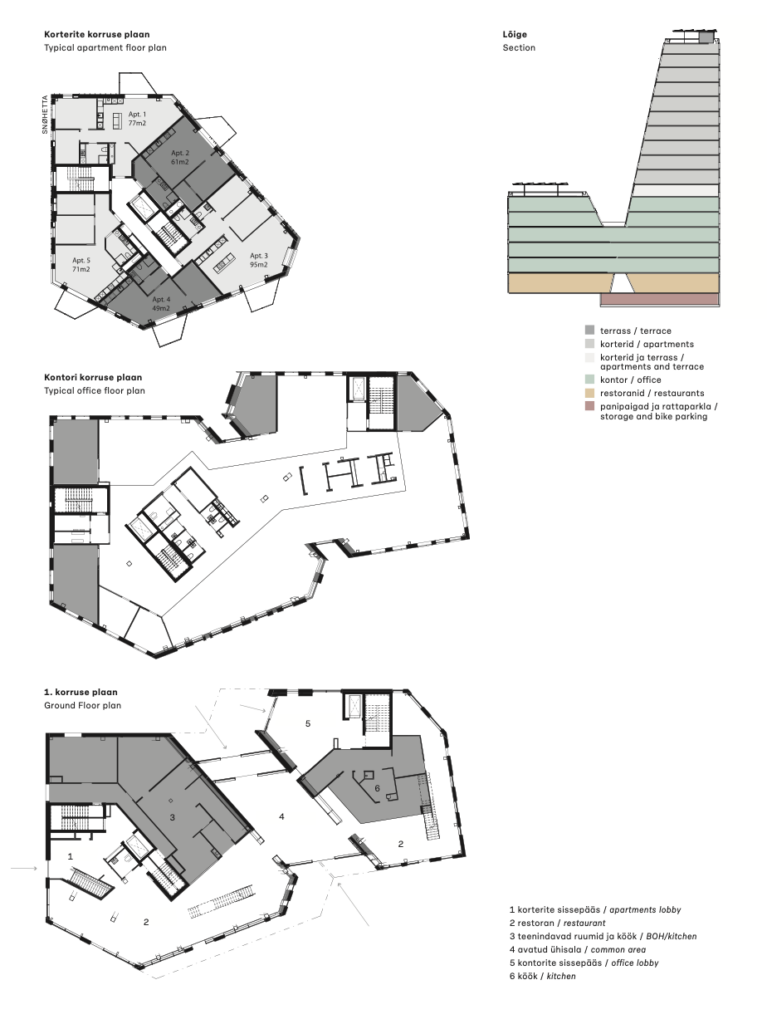

Type: Mixed-use building with restaurants, offices, apartments and roof terraces

Location: Nydalen, Oslo, Norway

Architecture, interior architecture, landscape architecture (roof terraces): Snøhetta

Landscape architecture (street level): LALA Tøyen

Client: Avantor

Research projects: LowEx, Naturligvis (The Research Council of Norway)

Contractor: Skanska

Size: 11 000 m2

Period: 2015–2024

Structural engineer: Skanska Teknikk

HVAC: Multiconsult

Electrical engineer: Heiberg og Tveter

Acoustics: Brekke & Strand

Fire: Fokus rådgiving

Water and wastewater: COWI

Vertikal Nydalen, a mixed-use building in Oslo designed by Snøhetta, pushes the boundaries of a modern natural ventilation system, writes Ott Alver.

Exception vs. rule

‘Architecture is a profession trained to put things together, not to take them apart.’

Architecture as a profession is largely concerned with the assembly of parts or elements. We architects are more interested in the functioning of the complete solution than the perfection of its each individual element. At the same time, we are ready to accept a good deal of unpracticality as well as out of sight messiness. On a scale from exception to rule, architecture generally leans heavily toward the former—in a world made wholly of exceptions, it rarely happens that details can be optimised by standardisation.

Thinking of the kind of architecture that leans toward rules, however, we could start with considering first principles thinking, the adherents of which have ranged from Aristotle to Elon Musk. According to the method, complex systems and seemingly ready-made ideas must be broken down into basic components, and each element needs to be considered separately. The point of this consideration is to ascertain whether any of the elements could be further improved, optimised, and to find out the limits of development activities. The situation needs to be examined with the eyes of a newborn, so to speak, by letting go of constrictive assumptions about how things work. An example from architecture would be the curatorial exhibition at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale, where OMA/AMO defined fifteen basic architectural elements, ranging from walls to lifts, and examined their development over time.

Looking at building components in isolation, one can see that they have undergone a long evolution. They have been affected by economic, cultural, political, sociological, etc. aspects. Components are used in compliance with the norms, regulations, and standards that have been set for buildings and facilities, but also with the general best practices in construction. Without much debate, many component systems or comprehensive solutions have turned into tacit agreements—we do as we are used to doing. It takes a good deal of initiative and desire to build from scratch, to question the status quo. Sometimes this task is taken up by an enlightened client, research group, research institution, or even architect.

In any case, creative thinking initiates a process in the course of which the evolutionary tree of basic architectural components will grow new branches—permutations—and new combinations will be consciously sought, which will in turn have a direct impact on space and spatial experience. There, just like in scientific research, it is important to let go of the pressure to find the so-called right answer—the purpose of a search is precisely to veer off course and hence find new associations.

Search engine

Basic questions about the elements of architecture were also tackled by Snøhetta architects in designing the Vertikal Nydalen building. Although the two-pronged building volume might at first appear simply a striking play with form, this design actually resulted from a series of studies and conscious choices. The project team members from developers to architects decided to focus their research mainly on ventilation. The research was carried out as part of the Norwegian state-funded interdisciplinary project Naturligvis, which focuses on developing new natural ventilation solutions.

The question of how to ensure sufficient air exchange in indoor spaces that would foster human well-being while maintaining distinct microclimates on the inside and outside has vexed mankind for ages. Over the last couple of centuries, several technical innovations have driven a complex evolution of ventilation systems. In this process, natural ventilation has largely been replaced with mechanical ventilation. To create these complex systems, a difference in air pressure is artificially created between different points of the building, often disregarding the possibility of making the air flow naturally—say, by relying on geometry and spatial planning. In the case of Vertikal Nyladen, however, the focus was precisely on developing a modern-day natural ventilation system.

Vertikal Nydalen is located in Nydalen, a neighbourhood in northern Oslo and a former industrial area that has witnessed a major development leap in the last 15–20 years. The area is desirable due to a nearby metro line stop and park landscape on the banks of the Aker River that features diverse public space and cycle paths leading straight to the centre of Oslo. The 18-storey mixed-use tower building was built on the plot of a former parking lot and soon turned into a new landmark of the neighbourhood.

What drove the developer and architect of this project to think outside the box? One major issue is the ever-increasing share of CO2 emissions in the life cycle of buildings that is contributed by the construction and maintenance of the technological solution. Airing out rooms by opening windows has mostly been replaced by a technological monstrosity that permeates the entire building: a heat-recovery ventilation device, trunking pipes, distribution piping, noise dampers, fire dampers, automation systems, air intake chamber, ducts, exhaust chimneys, soundproof dropped ceilings. This complex system is the result of our own increased expectations for indoor air quality, temperature, and humidity. We see that, over time, the complexity of ventilation systems has only grown. In the face of the 21st-century climate crisis however, it might be high time to ask whether that particular building component could be simplified.

Geometry

It will not do to merely omit complex ventilation pipes and devices. Rather, we could learn from the buildings built by past generations and understand the logic of their functioning. How did these buildings, lacking any technology in the present-day sense, manage to achieve efficient natural ventilation? In the Middle East, for instance, there was a special structure developed for that purpose—buildings were supplemented with windcatcher towers (badgir, malqaf, etc.) that were placed on them or next to them. A difference in air pressure is generated in the vertically divided ducts of the tower by facing the inlet towards the prevailing winds. The caught wind creates negative pressure in one duct and positive pressure in another, thus giving rise to the needed directional air circulation in the rooms.

In the case of the Snøhetta-designed tower building, the role of a windcatcher is fulfilled by the shape of the tower itself. Its multifaceted shape in plan is not due to Snøhetta’s trend-conscious design language, but based on computational fluid dynamics analysis of the building’s geometry. The analysis revealed that the air velocity between façades placed at different angles is greater than that between façades placed in parallel. This in turn helps the air to pass more quickly through the building. Furthermore, the building volumes converge towards the apex, speeding up the airflow on the outside surface of the building and thereby also inside the building—this helps to reduce the speed of ground-level winds around the building.

The whole

Natural ventilation requires comprehensive forethought—all components of the building have to support it. In Norway as well as in Estonia, a particularly critical moment for natural air exchange comes in the wintertime, when indoor temperature drops rapidly during ventilation. For this reason, buildings were historically equipped with large stoves, thermal walls or other heat-capturing elements that helped to maintain a stable indoor climate. In the Snøhetta-designed building, the central load-bearing walls and ceilings are made of thick reinforced concrete and left largely exposed for heat transfer. Reinforced concrete elements help to ensure a stable indoor climate by capturing and emitting heat in daily cycles. The solution works equally well for both heating and cooling. Without their sufficient mass, cold air would quickly begin to cool the structural parts and ensuring a stable indoor climate would become near impossible.

In addition to the concrete mass, the interior walls of meeting rooms are covered with a layer of clay. Water pipes in the walls either heat or cool the rooms, at the same time helping to maintain a stable humidity level. Heating and cooling are provided by deep geothermal wells underneath the building, whose pumps are powered by solar panels on the roof. Electricity is sold to the grid in the summer and purchased from it in the winter with the aim of reaching zero in annual terms. By combining several elements that are unusual in modern office and apartment buildings, Vertikal Nydalen has managed to create a comprehensive solution where all parts complement each other.

Hybridity

Snøhetta has combined traditional natural ventilation with the latest possibilities of modern technology. Automated systems in the building’s perimeter control the ventilation valves placed in the upper edge of each storey so that the warm and carbon dioxide-rich air over there would mix with fresh and cold air from outside. The valves are opened automatically by a central control system, whose sensors measure the temperature at different points of the room as well as the air quality (CO2, etc.). In this way, the valves on the opposite sides of the building are opened as needed and only at the right time, and the building is rapidly and thoroughly ventilated. Opening of the valves is also controlled by a weather station on the roof of the building that measures wind strength, wind direction, and humidity.

A novel system developed for the building consists in an application that collects feedback on satisfaction with the indoor climate from the actual users of the building. The real-time feedback enables one to control the indoor climate more precisely and adjust it when necessary. Anonymous feedback can be given by scanning a QR code next to one’s workstation. Based on the information aggregated from collected feedback and technical indicators, the indoor climate is managed and optimised as precisely as possible to respond to the users’ needs—in other words, instead of averaging, the system has been transformed into a needs-based one.

Limits of the system

Granted, it should be clarified that natural ventilation takes place only in certain parts of the building. The external walls of larger meeting rooms, for instance, have inlet fans that draw air into air socks made of perforated fabric, from which it is then slowly and more evenly released into the room. In this way, air exchange takes place over a larger surface, which helps to avoid local inconveniences with concentrated cold air. Obviously, there is also no natural ventilation in the bathrooms, which are equipped with exhaust fans. It is not expedient to have the same kind of ventilation system in each room.

The upper-floor apartments also adhere to more common standards—fresh air is drawn into the dwelling from valves in the exterior walls and contaminated air is drawn out through wet rooms. It is difficult to plan apartments as sufficiently large and fully open spaces that would enable natural air circulation.

Sustainability

In addition to the construction and maintenance costs of a building, it is also important to consider future-proofing and adaptability. Mechanical ventilation is mostly designed for a particular roomplan and a particular number of people—thus, it cannot be easily adjusted in the future. New tenants or functions usually mean that intricate technological parts need to be replaced. In this particular building, however, the automatic ventilation flaps in the exterior walls and the open floor plan provide a good basis for future-proofing. A single unpartitioned workspace is not suitable for everyone, but potential issues have been cleverly avoided by using the darker zones in the central part of the building for stairs, lifts, wet rooms and meeting rooms, thus dividing the open office into smaller areas without inhibiting the airflows necessary for natural ventilation.

Aesthetics can likewise be seen as a foundation of sustainability. Leaving out piping and technical devices that are very often senselessly space-consuming allows for higher ceilings that are clean of machinery, more open space, and an opportunity to display the authenticity of building materials and their technical performance, whether it be concrete, wood or clay plaster.

Scalability

Analysing how the solution could be implemented elsewhere, I noticed that the open workspace has a sparser-than-average placement of workstations. A smaller number of people means a smaller need for ventilation, and thus, natural ventilation can also be used in winter. Vertikal Nydalen is clearly a premium-class solution, meaning that it is expensive and difficult to adopt more widely. Instead of being overly critical, however, we should rather be envious of the fact that public research programmes in Norway enable so much innovation even with such a simple building typology. It is important to note that the solution does not comply with the current Norwegian technical standards and health protection requirements, so it had to be specially approved by the respective agencies. Allowing for exceptions in a sector that is otherwise relatively rigid is precisely what provides an opportunity for innovation.

In the Estonian architectural landscape, innovation is driven mainly by the public sector, which should then set an example for the private sector. Unfortunately, the search for innovation is confined to the individual projects of a few forward-thinking creators, instead of taking place in the framework of large-scale publicly funded research. At the same time, tightening ventilation norms and standards in the last 10–15 years have put architecture to the test in terms of budgets as well as space. A similar tendency was observed also by OMA/AMO in its ceiling-themed publication on basic architectural elements, where it was highlighted how technology has been forcefully proliferating in the realm behind dropped ceilings and walls, and how architecture has been unable to respond to it in an adequate way. Perhaps it is high time to take a fresh look at the topic of ventilation in Estonia too, and break down the current paradigms into their basic parts.

OTT ALVER is an architect and partner at Arhitekt Must. In spring semesters, he tutors architecture students at the Estonian Academy of Arts on housing.

PHOTOS by Snøhetta / Lars Petter Pettersen

PUBLISHED: MAJA 4-2024 (118) with main topic AIR

1 Rem Koolhaas, Elements of Architecture (Taschen, 2018).

2 Nick Tubis, ‘First Principles Thinking: The Blueprint For Solving Business Problems’, Forbes, 13 September 2023.

3 Rem Koolhaas et al., Elements (Marsilio, 2014).

4 „Vertikal Nydalen“, Snøhetta veebileht, https://www.snohetta.com/projects/vertikal-nydalen.

5 Rem Koolhaas et al., Elements (Marsilio, 2014).