The top-level conference held at the Estonian Academy of Arts during the Tallinn Architecture Biennale dealt with the effect of digitality on architecture, production processes and society.

Digital technology is changing how we design, what we design, and who we design for. It is clear that computation has changed the way we work. It is a technology of automation, of removing human activity from a task. Digital computers have replaced human computers – an actual job that used to exist. Soon most tasks requiring specialised skill or knowledge will, if profitable, be automated. This process is accelerating and starting to change what we design – increasingly it is processes rather than objects. Automation is becoming a question of design rather than engineering, of creating meaning not just problem solving. After we’ve realised, we have failed in isolating nature from culture, objective from subjective, and thus never really been modern, everything is a matter of design. „Matters of facts are turned into matters of concern“, as Bruno Latour argues.1 And, while designing these automated systems that condition our lives, we are designing ourselves. It is therefore inevitable, that the discussion on digital reality be a political one.

1. HOW WE DESIGN

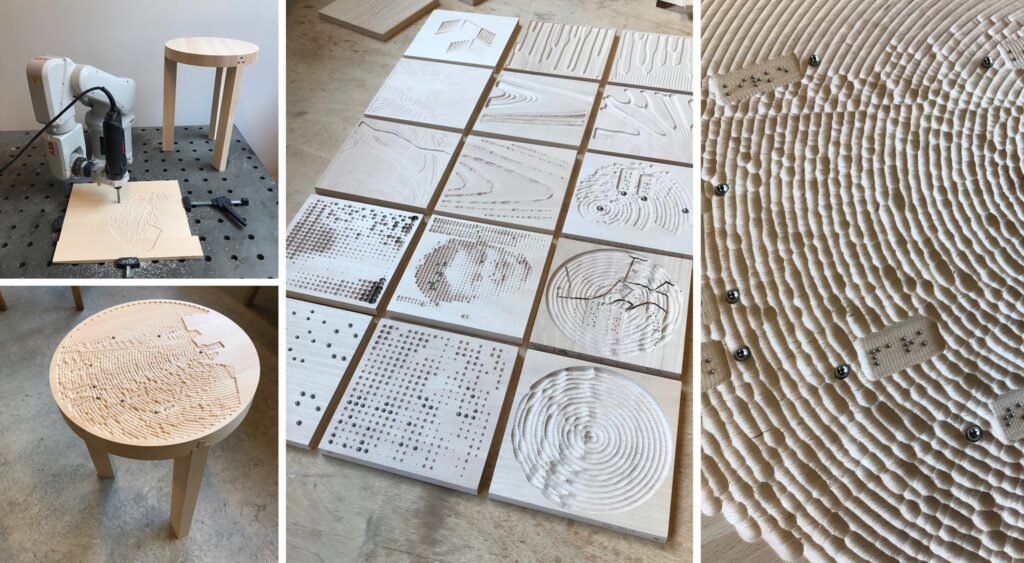

Ever since digital tools entered architecture in the early 90’s, one of the main questions has been the changing role of the author. This issue has many facets. For instance, using computer aided design (CAD), there is the question of who designs the tools. When one is using Bézier curves, is the Renault engineer Pierre Bézier granted some authorship? Also, one of the first reasons for adopting CAD software was the inherent editability of digital files, meaning many people can work on the same file and create versions of the same design, and not use a razor blade to delete lines. This ultimately leads to ideas of collective design, especially with the rise of the so called web 2.0, where the users are also creators of the content. 30 years into digitalisation of architectural design, we have also been through the fab-lab revolution – fabrication shops giving access to 3D printers, laser cutters, etc. – which has reintroduced the idea of craft into architecture. Computer aided manufacturing (CAM) tools have created a direct link between what is designed and what is produced (CAD–CAM), giving rise to a generation of so-called maker architects.

This became a heated debate in the panel discussion, after a question from the audience about whether digital tools could actually liberate the architect from technical, social and legislative constraints. Although historian Antoine Picon answered with a short „No!“, the issue is of course more complex. Most of the panelists agreed that the idea of craft, architects becoming artisans or even start fabricating their own buildings, just isn’t feasible. As Picon pointed out, most architects who have tried it, have gone bankrupt. Supported by architect and researcher Roland Snooks, who said that these tools of fabrication are for him design aids, giving immediate feedback about materialisation. As a designer is constantly looking for innovations rather than profitable models, there needs to be a divide between the designer and the manufacturer. Furthermore, as Snooks pointed out, rubbing up against constraints is what makes architecture interesting.

These issues of creative freedom and design agency were also touched on by multiple presentations.Talking about automation – removing the human from a task – it is important to note, that designing one’s own automated design tools is the only way of ensuring real creative freedom. This is how keynote speaker Roland Snooks creates his Strange Behaviour, using generative algorithms. He programs virtual agents to draw three-dimensional objects based on sets of behavioural rules. Gilles Retsin, in his presentation, argued for a fully automated approach in his meticulously designed discrete architecture, that is similarly generated by a script, a series of computational commands, rather than drawing or modelling. This is the same reason I argue for an algorithmically modulated modularity, an intuitive design method that employs automation to enable subjective intervention into this complex system of strict structural, economic and constructional constraints. This happens similarly to Bézier’s curves that are created by an algorithm, which translates the positions of a few control points into a smooth curve. Sille Pihlak is looking into collaborative design processes to prototype protocols for a parallel processing of design information creating an integrated model, where the architect is not just a composer, but also a conductor, to draw from historian Mario Carpo’s analogy between musical and architectural notation. Pihlak argues that digital technologies enable us to combine intelligence from different disciplines into a parallel-processed system, a commonplace practice in more forward-thinking projects today. Namely, architects and engineers can work together in design models that have structural analysis integrated into them.

Further, as shown by some bigger European manufacturers like CIG Architecture or Blumer-Lehmann, Grasshopper, an open algorithmic platform for design, is making its way into production as well. This software has become the main tool for integrated design and design automation, while enabling Collective Intelligence in Design that Christopher Hight and Chris Perry argued for in their 2006 AD, when Grasshopper didn’t yet exist. As Pihlak jokingly says, it’s a move from “design by committee” to shared expertise, resulting not in a camel but rather a unicorn. Or to use Michael Hardt’s and Antonio Negri’s political terms, shared agency creates the Multitude where individual inputs come together to form the whole rather than being processed into a unified simplification like the people. While digitalisation enables stricter regulation and control, digital tools at the same time allow us to use these constraints as tools in more creative ways.

2. WHAT WE DESIGN

Why is this dispersion of agency good news for architects one might ask? Architecture has always been political, about convincing people, that doing things in a certain way is better than another. So similarly, as we’ve seen with big data being used to meddle with recent elections, the political will of the multitude is still very much influenced by the same media that gives this multitude its voice. This knowledge was used just as much by Obama as it was by Trump. As more experts are involved in the design phase, architects also get more insights into the way these separate agents work and what the possibilities are, instead of being delivered a fixed solution. Which brings us to probably the biggest underlying topic of the conference – politics.

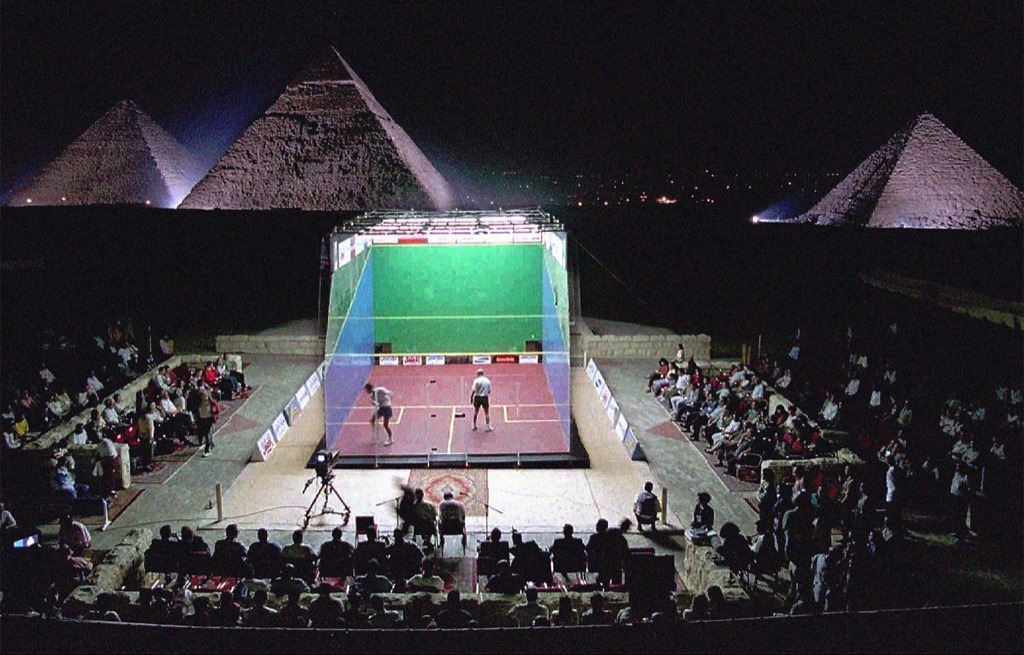

Roemer van Toorn pointed out, referencing Jacques Rancière, that there is politics within architectural knowledge, within the aesthetics itself. Architecture establishes relations and those relations are not always neutral. There are all kinds of constructions and value systems which unconsciously are in operation through aesthetics and they create situations and a framework for life. Van Toorn posed the question: „What kind of politics does technology make possible?“ „That kind of politics shouldn’t be about policing, as a lot of architecture is doing, but about dissensus – people and things that have no voice, should start to have a voice.“ With this Van Toorn wants us to invite the other, the migrant, also the migrant within us, to relate. In his presentation he argued for ethical spectacles as consumer culture, with its crafted fantasies and stimulated desires, speaks to something deep and real within us. In a way he is inviting us to ride the wave, but try to do it to more ethical ends.

Gilles Retsin had a more idealistic point of view. He argues that the growing inequality rising from automation is not a problem of technological advancement, but one of the social system that it is employed in, seeing the answer in left-wing accelerationism. He argues that the current social system will eventually collapse on its own, leading to a fully automated post-capitalist society. Within this fully automated luxury communism he argues for a discrete architecture of non-hierarchical building-blocks, which results in a fragmented architectural language of repetition, with ambitions similar to Hassumannian street fronts in Paris. The discrete architecture is meant to disrupt the whole building industry. Although most of his designs have taken the form of museums and pavilions, he is arguing these to be prototypes for social housing – turning architecture’s attention away from elitist institutions, like art halls and opera houses, towards the whole building stock.

Roland Snooks on the other hand argues for a humble position of the one-off experiment, saying he is more interested in the esoteric rather than the universal: „It takes incredible ego to think what it is that you are offering can be universally spread to every single person.“ These two illustrate quite nicely two opposing political positions that are very much related to the design language of these architects. This connects back to dispersion of agency that is central to democracy. One sees himself as an agent, among many in a swarm, who with their esoteric behaviour is affecting the whole, the other as the designer of the universal building block, that fundamentally defines how the whole can behave. Neither of them has ethical superiority, but the latter certainly has a bigger responsibility.

Antoine Picon implied Retsin’s idea of the universal building blocks is going back to some of the failed illusions of modernity, which believed it could be an elegant engineering of the planet. Van Toorn added that we have to be careful when claiming that the modern project totally failed, considering the state of the world after WWII and colonialism, what standardisation provided and how that introduced, on a large scale, the dwelling rights for instance, the rise of healthcare, etc. „We cannot just say that the project failed, we have to be very critical of the modern project but we shouldn’t stop asking what it means to be modern, we should take on board and experiment with alternatives even if we make mistakes.“

I think the digital is a lot more like blockchain – the more you spread out points of failure, the more safe, robust and arguably democratic the system is. This point is even more crucial, when talking about automation. The systems that we are setting up need to have political mechanisms built into them, from the ground up, to be possibly reinvented on the go, if needed. This could be achieved by making them non-hierarchical and modular so any part of them can be culled, replaced or reconfigured in case of failure. Designing these automated systems, hence, we should be very careful not to eliminate political agency. As was pointed out in the panel discussion: „Robots don’t go on strike!“

3. WHO WE DESIGN FOR

Which brings us to the subjects of these transformations. Gilles Retsin argued that „the story of digital craft, which has been lingering around, comes at the same time as the idea in Silicon Valley, that access to digital tools enables people to become autonomous, to start their own company. The whole idea of the fab-lab is: „Hey we don’t need to change the structure of society, let’s just give people access to tools,“ which is perfectly compatible with the neoliberal project.“ Picon continued: „And [these people] lose their jobs because of fabrication (or automation). It strikes me how little thought has been devoted to the worker. Digital Ruskinianism is an excuse not to think of the status of the worker.“

The discussion on automation and jobs divided the panel. Will the individual in an automated society live a happier and more authentic life after there is no more work, or will we all become slaves to the machines we have created. Or is there an alternative where work will be augmented by robots, but still include human labour? Presenter Wolfgang Schwarzmann for sure is a believer in the latter scenario. A hybridisation can already be noticed with robot-arms moving into woodworking facilities and the shift from manually skilled handcraft to machine-supported technical know-how. In Schwarzmann’s view, digital technologies will, on the one hand, help disseminate carpenters’ expertise through digitalisation of specialised joinery, for instance. On the other hand, robotisation will inevitably also lead to some loss of handcraft skills.

But the question of who we are designing for goes further than how and what kind of work we will be doing. Digital technologies have been pivotal in universal design. In addition to the well known accessibility functions of smartphones, there’s also possibilities of integrating haptics into robotically machined surfaces, for instance, as is the case in Dagmar Reinhardt’s research on Robotic Braille and Spatial Maps. But, augmenting our bodies with these mixed reality technologies has implications for all of us. Our bodies have been incorporated into urban data flows, as was pointed out by multiple presenters. Anarita Papeschi introduced her investigations using biometric sensing in participatory urbanism and design – literally using the human body as a sensor to investigate the city. One of the last presenters, Adrià Carbonell widened this topic by going from planetary networks of information and communication technologies to the urbanisation of our human bodies. We ourselves have become part of the data circulation. As our bodies produce and consume data, all of it needs to be transmitted, stored and processed using actual physical infrastructure that uses increasing amounts of resources and power while producing huge geological transformations.

Talking about geology. The highest earning category of workers in Australia are the fly-in, fly-out miners, as Roland Snooks pointed out. „Obviously this pushes automation. So now we have these massive mines that produce massive profit with no one working there but robots. So, now foreign multinational companies are extracting all the wealth.“ Less workers, means less salaries resulting in smaller tax income for the local economy. Picon reminds us that mines used to be instrumental in fostering social progress, because people could go on strike. In his grim prognosis, if robots take over, we will have unbridled domination of capital. On a more positive note he calls for a new equilibrium. We need to keep humans in as many jobs as possible. Looking at the immediate future, though, robots are definitely not the biggest problem we face: as Picon emphasises, „China is full of Taylorian line workers. The sad truth is that humans are very often cheaper than machines.“ The bigger problem is rising inequality.

So, whether we design museums or social housing, it all should be an ethical spectacle for the multitude. But, we have to keep in mind that just as much as digital technologies have liberated us as individuals, we, as the digitally enabled multitude, have also become bodies of data in a global network. This makes it possible to analyse and simulate behaviour of the masses with unprecedented precision and creates the possibility of manipulation on a global scale.Considering this, is the digital really an enabler of endless variation, as proposed by the first generation of digital architects, or rather a contingent system of standardisation? The biggest challenge pointed out in the conference is the concentration of power and capital and how to come up with integrative, open systems that can disrupt this propensity. Most people are probably not comfortable with the accelerationist idea of catalysing the inevitable collapse of the neoliberal capitalist system. Whether the digital will eventually be the source of social and economic liberation or growing inequality and automation of the apocalypse really comes down to the political decisions made in the process of designing the underlaying mechanisms of our digital reality. Architecture, as a provider of the social infrastructure, has a critical role in doing that.

SIIM TUKSAM is a junior researcher and doctoral student at the Faculty of Architecture of the Estonian Academy of Arts, and founder of PART – Practice for Architecture, Research and Theory.

HEADER: keynote speakers Mario Carpo, Roland Snooks, Antoine Picon. Photo by Lisanna Remmelkoor.

PUBLISHED: Maja 99 (winter 2020), with main topic Rural Insights

1 A Cautious Prometheus? A Few Steps Toward a Philosophy of Design (with Special Attention to Peter Sloterdijk)

Keynote lecture for the Networks of Design* meeting of the Design History Society Falmouth, Cornwall, 3rd September 2008 Bruno Latour, Sciences-Po. http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/112-DESIGN-CORNWALL-GB.pdf