MEMORIAL TO LYDIA KOIDULA AND JOHANN VOLDEMAR JANNSEN

Landscape architects: Terje Ong, Kerli Irbo ja Edgar Kaare (Tajuruum)

Sculptors: Bruno Kadak ja Mare Mikof

Architect: Tõnu Laanemäe (Symptom Architect)

Constructor: PVH Ehitus

Competition: 2016

The memorial was opened: 2018

The monument dedicated to Lydia Koidula and Johann Voldemar Jannsen near the Arch Bridge in Tartu may be discussed primarily in two respects – in terms of sculptures and landscape architecture. The memorial square strives for the human-scale but how successful is it?

Unfortunately, there are few monuments in Estonia erected for remarkable women. There is a larger than life marble statue of Marie Under in a folk-dance position in front of the National Library (authors Mati Karmin and Tiit Trummal), Betti Alver has an abstract memorial in Jõgeva (author Terje Ojaver) and Miina Härma is standing in front of the secondary school bearing her name in Tartu (author Juta Eskel). In addition, there are some monuments dedicated to mothers as well as many anonymous women, more or less covered or completely uncovered mythological characters in graceful poses.

So it is all the more remarkable when one woman is given already a second bronze statue. This happened to Lydia Koidula – she has crowned the park bearing her own name in Pärnu already since 1929 (author Amandus Adamson). Standing on top of a large rock typically of the era, the romantic figure remains somewhat unnoticed in the urban space. With the memorial square in Tartu, Koidula is brought among her people so to speak, as was also mentioned by the competition jury in their comments on the winning entry. Koidula has already been honoured in Tartu with a protected oak tree bearing her name at the corner of Pepleri and Tiigi Streets (between the Soviet buildings) that had reportedly grown in the garden of the poet’s parents, although there seems to be little truth in the story as she could not possibly have created anything significant under a tree that probably did not even reach her shoulders at the time. A more modern touch is given to her in the form of street art in the parking lot in Magistri Street, stamped on the wall of a former fuel station and current public toilet, featuring Koidula puffing on a cigarette with her hairdo still as dignified as in the school textbooks.

It would all be very nice, if only Koidula did not have to share the attention with her father Johann Voldemar Jannsen who has also earned his place of honour in the Estonian cultural history. It is not only about meanness or shared glory but also the selected expressive means. It actually received quite a lot of criticism soon after the announcement of the winning entry for the same reason – why should Koidula be a child?

It would be difficult to imagine a similar approach to the monument of some great men. True, a small bronze boy is dedicated to Arvo Pärt in Rakvere (authors Aivar Simson and Paul Mänd) but with a clear historic background: having lived in Rakvere until his secondary school graduation, Arvo used to circle around the square by bike listening to classical music from the loudspeakers attached to the post. And there is no patronising father figure anywhere in sight who could scold him or guide his talents in the right direction.

The small Koidula sporting her famous massive adult mane created by Bruno Kadak is running away from the square towards a random brushwood while the somewhat larger than life Jannsen of advanced age by Mare Mikof is sitting on a bench with a pipe in his hand and looking down. The man is indeed sometimes called Papa Jannsen, but why wasn’t the woman then depicted as the Nightingale of River Emajõgi or the Maiden of Writing? In reply to a comment about the fact that Koidula’s childhood was spent in Pärnu, Mikof stated (ev100.ee), “But that is irrelevant. She was her father’s child and that does not diminish her importance in the history of Tartu and the entire Estonia.” Let’s hope that women will become more independent in the future with no obligation to remain the children of their famous fathers until the end of their life and will have the permission to grow up.

According to the website of the city of Tartu, the sculpture includes an interesting intrigue by “placing Koidula and Jannsen among people and furthermore – by depicting Koidula as a child. As stated by the authors, the given manoeuvre allows to highlight Lydia Koidula’s memories of her childhood, her love for her country and also the theme of national awakening.” Recent sculptures all tend to be so to speak among people, in other words, life-size characters either sitting or walking and fit for taking selfies. There’s nothing peculiar about that. Also in Rüütli Street in Pärnu, the bronze statue of Jannsen (author Mati Karmin) features a man reading a newspaper among pedestrians. Although according to the dictionary, an intrigue stands for a conspiracy or a trick, the child-Koidula seems a bit silly and unconvincing, not to say degrading. Jannsen’s statue is not clever in a way befitting a university town, and I must agree with Meelis Oidsalu’s views expressed in Sirp (5 Oct), “I don’t know if anything and what exactly caused a dispute in Tartu, but if the decision-makers had made a bolder choice and erected the memorial with all the modifications we could see in Draakon Gallery (Jannsen wearing bright blue rubber galoshes and orange knitted gloves), we could be talking about a sculptural ensemble worthy of “the city of good thoughts”.

Be that as it may with the creative freedom of the artists and the taste of the audience, but the small square is also marked by pronounced pathos. Monuments have been brought down from the pedestal to diminish the distance from the so-called common people, however, the plaques of poetry still remain exceedingly solemn and presumably fully incomprehensible to visitors and tourists. They may be the key figures of national awakening but is the only way to appreciate Jannsen really by reading the patriotic lines from the bronze plaque underneath his seat in a trembling voice, “In every place with Estonian people / You hear their boundless love / For the land of their fathers / In their ardent song of praise”? And the children’s song “Our Childhood Village Lane” selected from Koidula’s works calls for resisting the temptation to leave one’s country and staying put instead, appreciating and coming to terms with the abode. The selection seems to have been guided by the current overwhelming national pathos accompanying the country’s anniversary gifts that does not allow the story to be retold, for instance, in English either.

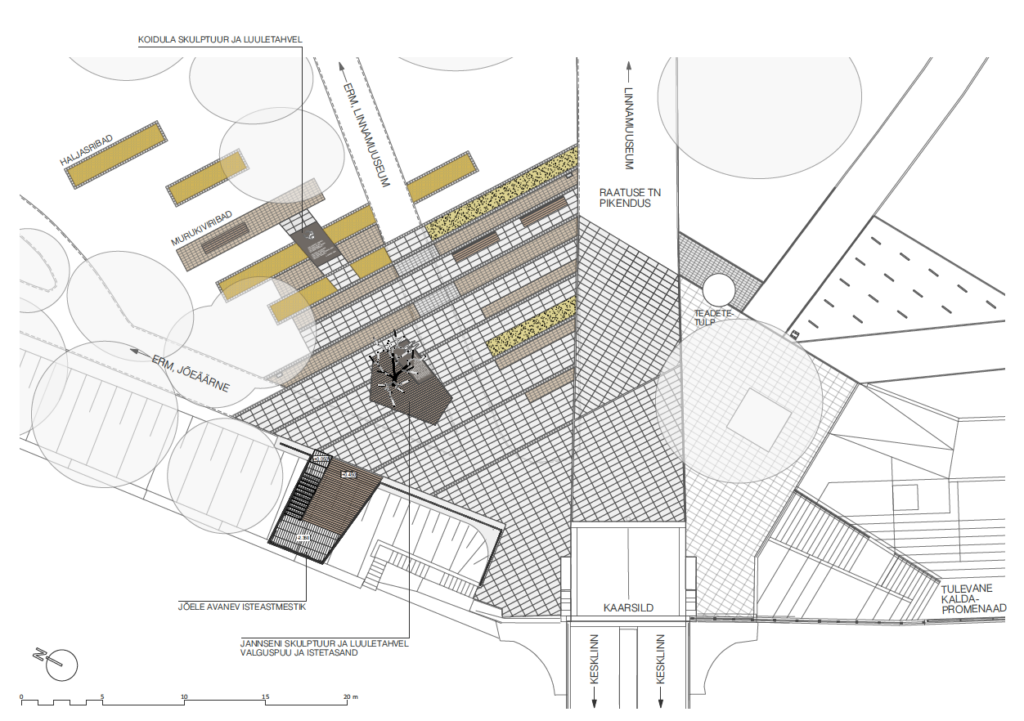

In addition to the symbolist meanings, the square accentuating the urban space fortunately comes to convey also some less complex physical and spatial ones. So for instance, the memorial square has given a clear identity and function to the sordid intersection at the end of the pedestrian bridge where the old-fashioned advertising column used to be the only thing inviting you to slow down on your path. Ülejõe Park looks somewhat random and chaotic, some consider it even unfriendly and dark, so the new square will certainly bring new life to the area. The contemporary public space created by the memorial square firmly anchors the city at the other end of the Arch Bridge.

Recent sculptures all tend to be so to speak among people, in other words, life-size characters either sitting or walking and fit for taking selfies. There’s nothing peculiar about that.

Tajuruum is an office of young talented landscape architects who have convincingly proven themselves and thus become increasingly visible in the urban space of Tartu. The memorial square of Koidula and Jannsen follows their distinctive style: minimalism with clear lines and the uses left modishly free. It is precisely the landscape architecture of the small city square that tones down the pathos of the sculptures and lines of poetry and actually brings the public space closer to people.

There is a seating area on the bank protection of River Emajõgi with its steps leading closer to water and opening new views that differ from the traditional ones from the park paths. The airiness of the terrace raised slightly above the ground is enhanced by the black metal railings as well as the metal grate flooring contrasting to the warm wood of the seating steps. Then again, the environmental impact of the rubbish sieving through it and into the water is, of course, another matter. The square solution is relatively simple making use of various surfacing materials, there are narrow strips between the large concrete slabs created by seams and stones of various size that gradually join the vast lawns of Ülejõe Park with the Arch Bridge and the concrete surface of the city streets. The narrow planting beds similarly follow the same style. The beds of perennials and flowers that were considered romantic in the competition entry sketches have not taken shape yet, however, the planting schemes suggest lush slum greenery which probably refers to the above-mentioned poem by Koidula (knee-high meadow with flowers and grass). Hopefully, the growing plants will eventually shrug off the wooden sticks and rope of the borders around the bed.

Similarly, we can only hope that the idea suggested in the competition entry to make some space for a small business or the City Museum’s play or exposition area will be realized as then the square placed in an important route intersection would actually be in active use extending its annual time of use. Also various formal or spontaneous events could find their venue there, as it does provide space for self-organisation. This would help to bring more vigour to the space that at present is perhaps somewhat pragmatic and practical at the city government’s pleasure (as emphasised during the competition).

Sculpture and landscape architecture seem to be of oppositional nature here in the tiny square with the solemn bronze competing with the human-scale space and the patriotic with the popular. Time and the users of the space will tell who gained the upper hand.

ELO KIIVET is an architect and urban designer working at Linnalabor, teaching architecture and editing the architecture pages of the cultural weekly Sirp.

HEADER photo by Uku Peterson

PUBLISHED: Maja 95 (winter 2019), with main topic Drift