Any apartment complex can become a community house if its inhabitants are so in sync that while they need to meet up (cooperative activities) they also want to come together.

There aren’t many houses that have been constructed by their community from the very beginning. As far as we know, there’s no research on it but people are probably afraid of relationships going bad, not getting loans, the indeterminacy of the process and the lack of initiative and time.

However, this kind of jointly built townhouse would encourage young families to stay rather than to move to the suburbs. There’s plenty of free space in central Tartu and nearby areas but due to land prices, graduates and young families don’t dare think about building. Developers’ houses are also pricy and usually exhibit boring mainstream features to “make the most of the space”. Our homes go beyond our front doors: both the immediate and wider urban space has been part of our living environment for a long time. The built-to-sell apartment buildings’ anonymity doesn’t kickstart community growth. Additionally, the developer acts as the owner and manager of the building long after construction has finished: you can’t even change your own lightbulb. This approach might suit some people, but those who yearn to interact with their community tend to escape from over-regulated life and put down roots in the countryside or in Karlova or Supilinn.

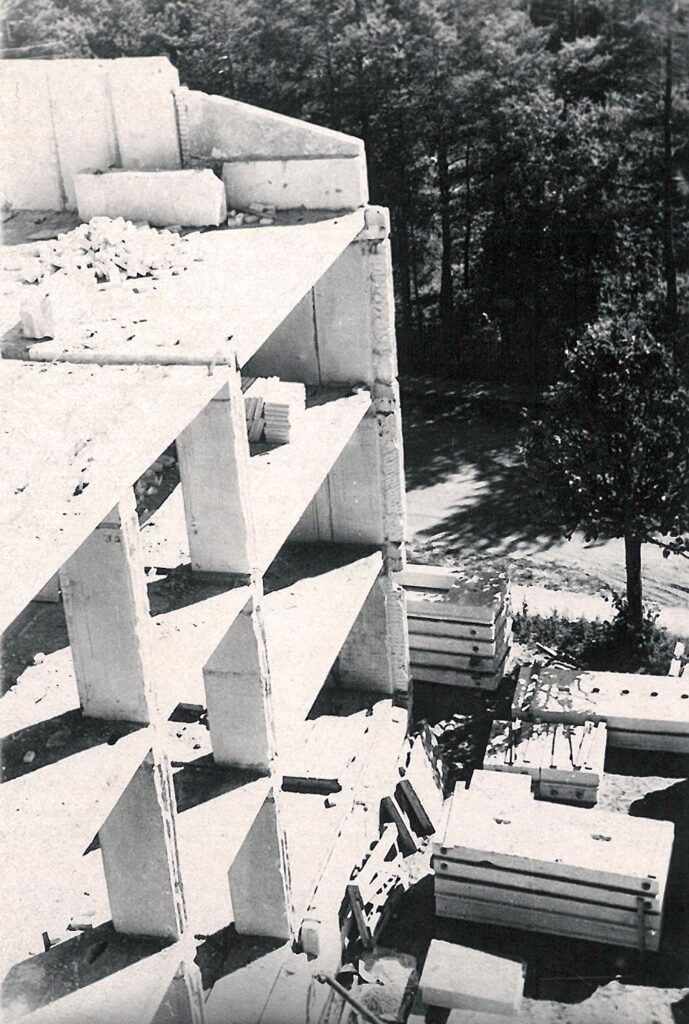

In Soviet times, the prerequisite for getting an apartment was queuing for them. You were eligible for the list if your family had less than three square metres of living space per person. When constructing a new building, the queuers formed a cooperative that founded the community. These populations formed rather randomly, even if the inhabitants were employed at the same institutions. Cooperative houses were constructed by housing plants.

The Silicate Concrete National Institute for Research and Design Autoclave decided to try out a new model – the cooperative was comprised of people based on their potential contribution. This meant that all future inhabitants came from that institute but their competences rather than their place in the queue was the criterion for being chosen. There were architects, welders, engineers, electricians and automaticians. The other half was chosen from those who were able to operate the conveyor at the test plant of the institute and actually make the building blocks themselves.

All members paid the bank 1,300 rubles (there are 18 apartments in the building) to found the cooperative; additional payments were made later. The bank controlled the funding, and the cooperative had an accountant and a review panel. A separate account was created for the cooperative, and materials were bought. As this was an experiment, the manufacturer supplied materials at a lower price (ones that were not made by the inhabitants). Kerese 33 was the first cooperative in the Estonian SSR to get that right and privilege.

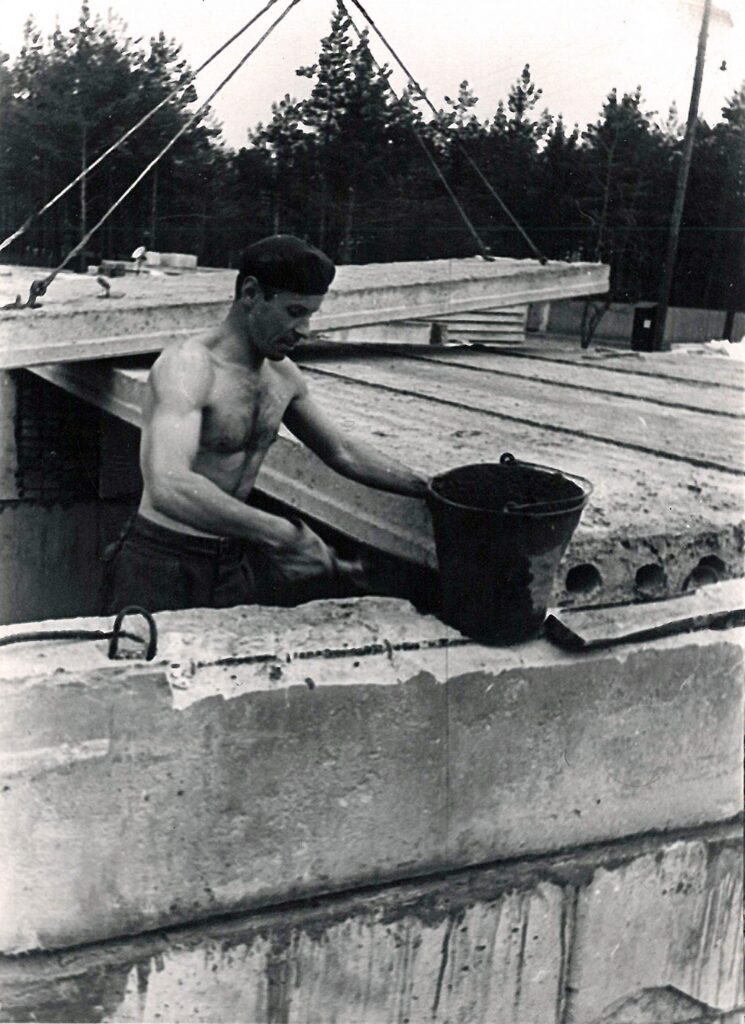

Everything to do with the construction was decided democratically at meetings. People worked on the building after their workdays, during weekends and vacations, and on public holidays. Work hours were calculated per family, and they totalled 2,500-3,000 hours over these three years. Those who couldn’t contribute by building sometimes opted to pay 20 rubles per hour to the joint account. That was a way of getting cash to buy rarer materials or pay the builders. A renovation fund was also established.

Once the building itself was ready, the apartments were allocated by drawing lots. Those who had contributed the most hours got the first pick. The floor plan of the apartments was identical, and two more houses were built following this blueprint.

While the general construction of corridors and joint spaces was done together, everyone was at liberty inside the four walls of their apartment. The Commission of the Executive Committee allowed people to move in once the kitchen, toilet, bathroom and one room out of three were done.

The house was supposed to have a sauna, but it was never built. Out of the planned common spaces, a laundry room, a wood and metal workshop (the saws and planes are still in working order), a 70-square-metre party space (special order furniture and kitchen), a darkroom for developing photos, cellar boxes and spaces for storing bikes and sledges were constructed.

Initially a boiler room was also designed, but the cooperative managed to join the Männiku central heating enterprise. The heat lines were dug by the inhabitants themselves. They also installed plumbing. The network ran straight through the private properties.

The inhabitants got on perfectly, and life-long friendships were made. They celebrated birthdays and New Year’s Eve together and organised anniversaries. The lot was designed and cleaned up in the spring and summer on communist Saturdays. Twelve of the eighteen original inhabitants (their families or descendants) still live in the building.

The video for Entel-Tentel’s song “Hei, hei” was filmed in the stairway and garden.

Kastani 127A, Tartu

The house has eight apartments. The now stable future group of inhabitants is composed of friends and acquaintances from before. The group comprises landscape architects, an architect, a heritage conservator and a graphic designer among others. The inhabitants have had a say at all stages of the project, both concerning their own apartments and common spaces. They have designed the outside space (vertical planning, parking spaces, terrace dividers, greenhouses) and there was a time the project manager was also a future inhabitant. By now they’ve hired a construction project manager.

The current owner of the land is a developer who finances the construction and the apartments will be bought out from them. Banks don’t fund this type of development (yet).

The constructor will build the apartments according to the inhabitants’ DIY wishes, allowing them to finesse the details. They hope to construct the garden, chicken coop and wine cellar on their own.

It is a wooden house made of pre-manufactured elements. They will probably join the city’s central heating system, but the building will also have two chimneys so those interested can build ovens or fireplaces. There is a small cellar that contains the boiler and also fits chest freezers. The ancillary building (a potential sauna) won’t be completed during the first stage of construction. The building will start this year.

Today banks don’t dare to give loans for constructing communally built houses. Yes, it might be plausible if there’s an airtight warranty, but friendship groups are diverse and heterogenous. Not to mention that many graduates of the University of Tartu and other young specialists are often from elsewhere. Professor of architecture Toomas Tammis from the Estonian Academy of Arts finds that if there was a way to sensibly support constructors then it could change the urban space as drastically as handicraft production transformed the alcohol market. Keeping people inside the city and creating a home to fit your every need is a huge step in the right direction in modern urban development – we’ve tried everything else.

Jarno Laur, former vice mayor and current rural municipality mayor of Tartu, pointed out that Tartu actually has an institution that other cities lack and that could potentially initiate processes like this – the Housing Fund of Tartu. Right now the fund mainly helps citizens out with housing loans, cooperative loans, and water and sewage systems. Guaranteeing the community house loans could be the fund’s new function and might give Tartu a huge development advantage. If this process was kickstarted, then real estate developers would also probably rethink their old ways, give up rigid, top-down construction and begin cooperating with potential inhabitants right away, not when all is said and done and they can only choose the wall colours. A self-designed home and previously made friendships ensure apartment complexes function better – they build bridges between inhabitants as well as the individual and the town.

KARIN BACHMANN is a landscape architect and one editor-in-chief of Maja’s 2019 winter edition (95).

HEADER: P. Kerese 33, Tallinn. Time of construction: 1965-1968. Architect: Lia Plaks (inhabitant). Interviews, November 2018: Thea and Rainu Trautmann, Elge Lomp, original inhabitants. They helped build the house. Thea designed the plumbing system. Photo: private collection.

PUBLISHED: Maja 95 (winter 2019), with title Drift