What changes will the administrative reform bring to spatial planning as seen from the level of the state? Many decisions made by local governments have an impact on space, so how can we make these decisions more informed?

The objective of this article is not to assess the consequences of the administrative reform on the administrative capability of local governments as a whole. A collection of articles that focuses on impact is being prepared under the leadership of the Ministry of Finance. In this article I try to give meaning to the changes and consequences that the administrative reform may bring about in spatial planning.

A framework offered by the theory of environmental impact assessment1 helps in understanding the consequences, according to the framework it is possible to distinguish between associated changes, impacts and consequences. Although there are other theoretical frameworks, this approach is excellent for distinguishing impacts from consequences – but forecasting the latter is often difficult.

Impact and changes of administrative reform

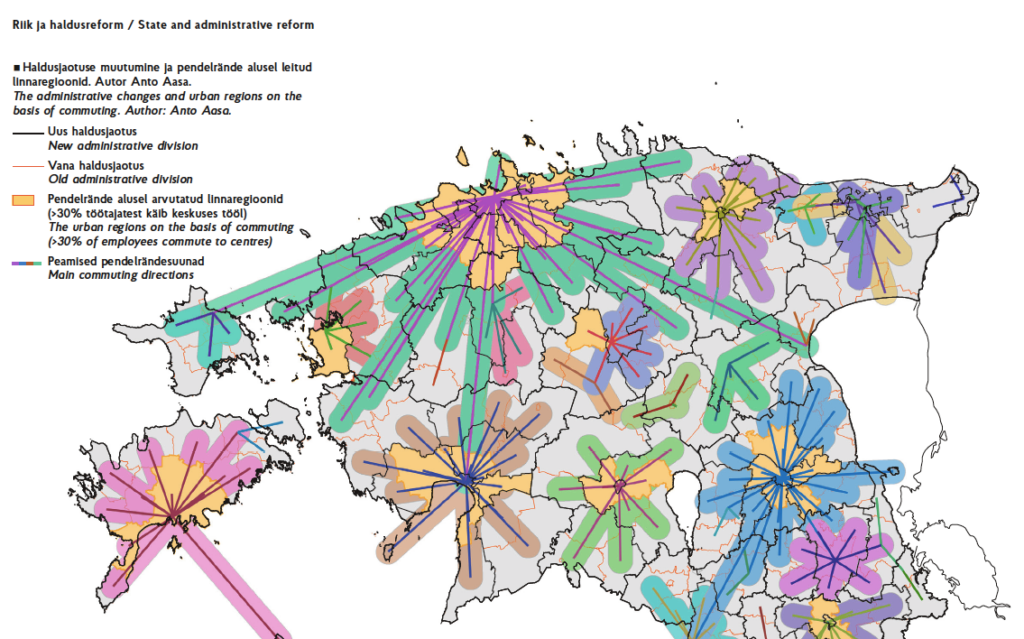

As the Minister of Public Administration recently said in his presentation at the Tartu Planning Conference, the administrative reform has brought about the following objective changes.2 The average number of residents in a local government today is 17,118 (6349 prior to the reform). The average area of a local government is 550 km2 (previously 204 km2). Thus, Estonian local governments have grown by 2.7 times on average.

19 per cent of local governments have fewer than 5000 residents after the administrative reform (previously 79%). 35 per cent of local governments have more than 11,000 inhabitants (previously 8%). Approximately two-thirds of local governments are towns and municipalities with fewer than 11,000 residents after the administrative reform – previously, 92 per cent of local governments had fewer than 11,000 residents.

Impact of some of these changes from the viewpoint of spatial planning:

- local governments are larger in terms of territory and there are more people who may submit applications for the initiation of planning, which means that one decision-maker will prepare more plans per unit of time;

- as the territory of a local government is larger, the decision-maker will be making planning decisions in bigger territories, which means that there are more local circumstances that the people who make planning decisions must be aware of.

Consequences of administrative reform

What results would we like to see in spatial planning and on what basis can we assess progress towards the desired goals?

Increasing the planning competency of local governments is certainly a desired development trend.3 At present, many local governments do not have specialists on their staff who meet the requirements set for planners in the Planning Act.4 This does not mean that the act is being ignored – Estonian legislation does not oblige local governments to have the relevant specialists. We can take the example of Finland for comparison, where the law requires each municipality with more than 6000 residents to employ a planner.5 For the record, several conditions follow in Finnish law as well –municipalities may share a planner and the competency of another municipality or municipal association may be used; the ministry may also permit non-compliance with the requirement for a specified term.

Irrespective of the regulation, it is difficult to argue against the fact that a local government must make competent spatial decisions. The simplest example here is planning decisions whereby the decision-maker has to understand what a certain solution will bring about in spatial terms, and see this on a broader scale, e.g. in the territory of the entire local government. In addition, space must be kept in mind in the case of all decisions made by local governments: what changes in the use of space will the closure of a school bring about? What must be adjusted in public space when money is allocated for the construction of a promenade as a result of budget negotiations – for example, do related infrastructure and the procedures for its use guarantee access to the promenade (network of light traffic paths, car park and its regulation) and can the emergence of services in the surrounding buildings be promoted? A large number of local government decisions have an impact on space, and a specialist who has the professional competence required to assess the consequences of these decisions on the use of land and space must participate in the preparation and implementation of these decisions.

Could one of the consequences of the administrative reform be that there is a specialist working in each local government (and involved in decision-making processes) who has acquired education and work experience in the area of spatial planning? The preconditions of the recruitment decision are that the local government must be able to pay remuneration to the specialist, the specialist’s work is effective and their workload is sufficient. The financial capability of larger local governments will certainly improve, but there is no doubt that also in the future some activities will be more highly prioritised for decision-makers and bring gains more quickly than spatial planning. A simplified approach would be to count the appropriately completed planning procedures as a performance indicator. Local governments should try to achieve planning decisions that support the comprehensive spatial development of the local government.

The data in the overview of planning activities in 2015 can be used to forecast the workload of a planner6. It must be kept in mind that the quantity of plans depends on the regulation (the detailed plan requirement has decreased in the current law) as well as the general economic climate.

According to the data in the overview, eight detailed plans on average were adopted in Järva County and 20 in Viljandi County over a period of one year from 2011-2015. If we divide the number of detailed plans between the local governments in the county, we have to conclude that the number of plans per decision-maker will increase after the administrative reform, but there will still be local governments where only a couple of detailed plans will be “on the table” in a year, which is certainly not adequate to guarantee the workload of a competent specialist in one local government. However, we may not and cannot conclude from this that a local government should not guarantee the existence of planning competency. Local governments must arrange for officials to be shared between them, establish centres of excellence or find other ways of guaranteeing competency.

The second desired development trend is that those affected by or interested in decisions concerning land use are involved in making them. As said above, local governments have become bigger as a result of the administrative reform. The consequence of this could be the opposite to the desired development trend – the decision-maker and the decision move further away from people.

Conclusively, a possible positive consequence of the administrative reform that can be highlighted is the increased likelihood of local governments employing specialists competent in spatial planning. However, even after the administrative reform, not all the local governments will have enough plans to justify hiring a full-time planning specialist. The administrative reform comes with the risk that decisions will move further away from people.

How could negative consequences be prevented and positive ones enhanced? Recommendations for realising a positive consequence – increasing competency – have been given above.

In order to prevent the possibility that inclusion in planning decisions worsens as a result of the administrative reform, I would suggest the preparation of a comprehensive plan as one (but certainly not the only) mitigation option. Pille Metspalu writes more about comprehensive plans in this edition.

The preparation of guidelines for comprehensive plans is nearing completion in the Ministry of Finance. The guidelines are based on the experience of preparing comprehensive plans in Estonia and emphasise the main points that must be considered upon the preparation of a new comprehensive plan. The guidelines should be ready in early 2018.

Longer-term view

In changing circumstances, we have to ask about the relevance of the planning system as a whole. “Planning is not the tail that wags the governance dog,” write planning researchers Philip Allmendinger and Graham Haughton.7 When the dog changes direction, the tail has to follow. It is necessary to analyse what overarching processes like the administrative reform and the state reform mean for spatial planning. In order to assess the relevance of the bigger picture, we must also ask what the role, impact, and added value of spatial planning are in the light of ever strengthening sectoral spatial decisions.

The Planning Department of the Ministry of Finance is preparing a Green Paper on Spatial Planning. The goal is to find answers to questions in spatial planning that need to be reconsidered in the changed circumstances and to try to solve the problems that have been carried over from one version of the Planning Act to the next. For example, the planning instruments of the state and local governments and their functions must be redressed following the elimination of the institution of county governor. It is necessary to analyse whether the central role of the local government as a maker of planning decisions that complies with the idea of the Planning Act has been realised in everyday planning practices. Legal or other institutional amendments may, but need not, follow the preparation of the Green Paper. Information about the Green Paper process can be found at planeerimine.ee/prr.

TIIT OIDJÄRV is the Head of the Spatial Planning Department of the Ministry of Finance. He has previously participated as a consultant, especially in the area of impact assessment. He studied sociology at Tallinn University.

Article is published in Maja’s 2018 winter edition (No 92).

1 See the discussion about the use of terminology in environmental assessment, e.g. Glasson, John; Therivel, Riki & Chadwick, Andrew. (2011). Introduction to environmental impact assessment. London: Routledge

2 The election results had not yet been announced in all local governments by the time this article was written. The data are for local governments within the administrative borders in which the elections of local government councils were organised. Data from the Regional Administration Department of the Ministry of Finance (3 November 2017).

3 For example, the same requirement has also been set in the document “Overview of the state’s planning status from 2011-2015” (https://eesti2030.wordpress.com/avalikud-arutelud/ulevaade-riigi-planeerimisalasest-olukorrast-aastatel-2011-2015/).

4See clause 4 (6) 1) and clause 6 10) of the Planning Act.

5 See § 20 of the Maankäyttö- ja rakennuslaki.

6 Reference above.

7 The Fluid Scales and Scope of UK Spatial Planning. Philip Allmendinger, Graham Haughton. Environment and Planning A. Vol 39, Issue 6, 2007