Community-led housing development is leading the way from speculati ve to non-profit housing construction models. Eneli Kleemann and Helena Rummo discuss the spatial possibilities that come with it.

Housing unaffordability is no longer a problem limited to the underprivileged population but a much wider concern. It is also difficult for Estonians earning an average salary to find housing with a reasonable price tag that would meet their needs. The journey from effect to cause points to the fact that a disproportionately large amount of land has been privatised in Estonia, thus closely linking price increase to the private sector and volatile economy. In the urban space of Tallinn, the tendency is manifested in increasing segregation. Housing as a purely profit-making asset, that is, the commodification of housing is a political problem with its neglect further exacerbating economic inequality, which is why for many people finding a home that meets their needs will remain a mere dream. The tendency to consider housing as an economic investment leads to treating it only as an easily replaceable commodity. It diverts attention away from the long-term social goals such as housing affordability, reduction of economic inequality and strengthening a sense of belonging.

Other states and cities in the world have introduced measures to discourage housing speculation with higher taxes on renting out homes, increased land taxes on secondary property ownership as well as subsidies for non-profit housing initiatives. There are also requirements for developers to create added value with their projects by necessitating public realm improvements or social provision (e.g., providing social housing). In the past decade, several European countries, led by Germany, Switzerland and United Kingdom, have seen a boom in not-for-profit housing developments. In the given countries, the community land trust (CLT) system has gained popularity. In the case of CLT, the plot on which the housing cooperative is located is owned by a non-profit organisation, that leases it to the housing cooperative on a long-term basis. CLT ensures that the plot will remain in cooperative ownership and the housing is protected from speculative price increases.

Could cooperative development and ownership have a positive impact also on the Estonian housing stock? Looking at the current Estonian apartment association system, each flat operates as a state within a state. All households live under one roof but operate separately. The difference between cooperative development and the Estonian apartment association system lies precisely in the aspect of real estate speculation, where the members of the apartment association can independently and arbitrarily sell or rent out their flat profitably with no need to consider the wishes of other residents. It means, among other things, that when buying a home in the current situation, an Estonian earning an average salary might have to compete with foreign investors, e.g., Finnish pension funds. Such investments increase the anonymously profit-making housing stock, where the lowest rungs of the housing market are taken by Estonian wage earners. These kinds of liberal development trends outweigh the taxable square metre and override spatial decisions, that might bring more long-term benefits to the residents and their living environment.

What is this thing called cooperative?

The shared form of ownership, or cooperative, means that the living environment is decided upon and shared jointly. Estonia is dominated by the cult of private property and it is not really habitual to look beyond one’s flat or plot, although sometimes community spirit and cooperation makes its presence felt here and there. For instance, the initiatives of the local community society Uue Maailma or the Information Centre for Sustainable Renovation in Paide bring together communities acting for common spatial goals. The communal activities in Paide led to their own currency and community café while Uue Maailma subdistrict got their own community building, publication, radio and street festival. The community gardens established in the past ten years are another good example of cooperation.

There have even been attempts of co-construction in Estonia too. In her article ‘When a Neighbour is a Friend’ in the winter issue of Maja in 2019, Karin Bachmann gives two respective examples. The first one is an experimental Soviet cooperative Kerese 33 formed on the basis of the residents’ construction competences and wish to participate in the project. In other words, construction was voluntary, as they went to build the apartment building after work, at weekends, on public holidays and during vacation. The other example is more recent at 127a Kastani Street in Tartu where the residents were comprised of friends and acquaintances. Originally, the development and construction was to be financed by the plot owner , who would then sell the flats to the residents. The plan was to build the community building according to joint ideas. Today, this project has unfortunately been carried out as a conventional profit-oriented real estate development.

Cooperatives radiate democracy—the building belongs to the cooperative members with equal votes, who have control over the building and serve common economic, social and cultural goals. Such an approach allows to ensure a stable and safe living environment for individuals and families, who would otherwise have to settle for homes that do not meet their needs. Residents have no right to buy or re-sell their home, therefore keeping its value unchanged over time. In case a resident leaves the cooperative, they will be compensated the amount they invested at the beginning in its new value and the new resident can enter under original conditions. In addition to affordable prices, cooperative housing also reflects other social needs, for instance, community life, social inclusion, equality, environmental health and ethical funding.

When talking about the approach taken by European cities to tackle the housing crises, we should consider completed projects, including outstanding cooperatives as well as community-based real estate developments. Successful examples of cooperatives include Mehr Als Wohnen in Zürich, Granby Four Streets CLT in Liverpool, La Borda in Barcelona and Spreefeld in Berlin. It is also worth noting, the ongoing real estate developments of the non-profit Urban Coop Berlin focusing on the design and development of cooperatives. The process includes collaboration with the city, finding a suitable plot, getting funding, finding members for the cooperative as well as its design and construction. It is a good example of the collaboration between the city and the developer: the city leases plots to developers on the condition, that 20% of the development will be social housing.

Such developments with a new lease of life also offer welcoming challenges to architects, who find themselves rethinking the traditional architectural clockwork. An architect joining a community-based development can and perhaps even should be a part of the community or at least stand for the same beliefs. Whether a completely new building or a reconstruction, designing cooperatives would allow us to play out forms of housing that have never been tested in Estonia before. The excitement and flexibility of creating new typologies should set any architect’s pulse racing.

A case study:

Mehr als Wohnen, Zürich, Switzerland

Plot: municipal land provided by the city to develop cooperatives

Developer: a consortium of more than 30 Swiss cooperatives

Funding structure: 185 million euros

– Financial contribution of 30 cooperatives

– Loan from the city of Zürich

– State aid (for cooperative development)

– Loan from a commercial bank

Price of housing: 20–30% lower than the market price

Subsidised flats: 20% of the flats (with their income below the poverty line in Switzerland)

Other flats: 10% of all flats are reserved for charity organisations working with disabled people, immigrants or families with dependent children

Architects: Futurafrosch in cooperation with Duplex Architekten, Müller Sigrist Architekten, Pool Architekten, Miroslav Šik, Müller Illien Landschaftsarchitekten

Completed: 2015

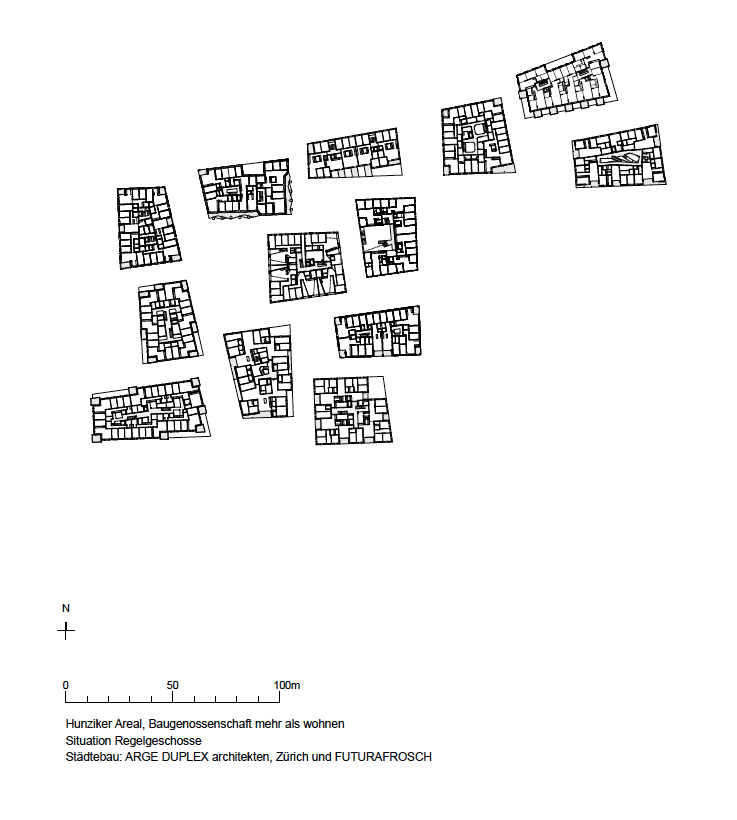

Mehr Als Wohnen (More than Living) is a building project completed in Hunziker Areal in Zürich in 2015. The area is like a microcosm containing, in addition to 370 flats, also a restaurant, guest house, shops, studios and other indoor and outdoor spaces of various use. It also provides work for 150 people and home for 1200 residents of various background and housing needs. One of the key effects of the development is the residents’ strong sense of community reflected in their possibilities to participate in decision-making processes and jointly create their living environment. They actively collaborate and participate in workshops, voting and political processes.

In 2011, as a result of a local referendum in Zürich, it was decided the proportion of non-profit housing in the city should be increased to 33% by 2050 (currently around 23%). In order to develop affordable housing, the local government decided to lease several plots on favourable terms. One of the selected plots was Hunziker Areal, the location of Mehr Als Wohnen. The four-hectare area on the northern edge of the city had earlier been an industrial wasteland located next to a former waste treatment plant reflecting the unfavourable image of the district. A consortium of more than 30 cooperatives was formed for the development collecting various funding, including loans from the city and commercial banks as well as financial support from cooperatives and the state.

In Switzerland, cooperatives are entitled to various amounts of tax benefits depending on the canton where they are located. In return, they are required to invest the generated income in services and premises in public interest. This was done also by Mehr Als Wohnen, as they offered their ground floor premises to encourage local business. In case of some initiatives, they cooperate with public organisations supporting the young and the elderly . Also, there are ten non-commercial common spaces available to all residents with their purpose determined by the residents themselves.

In cooperation with the city of Zürich, several important social and environmental goals were set. For instance, 1% of the development premises had to be given to the city free of charge to diversify the complex with public functions. Thus, there is a kindergarten, a nursery and a curative education school on the ground floor. In exchange for the long-term lease of the plot, the development had to include municipal housing that is 20% less expensive than the remaining flats and meets the spatial requirements of subsidised housing. Thanks to the above, cooperatives provide less expensive housing and contribute to social and sustainable urban development.

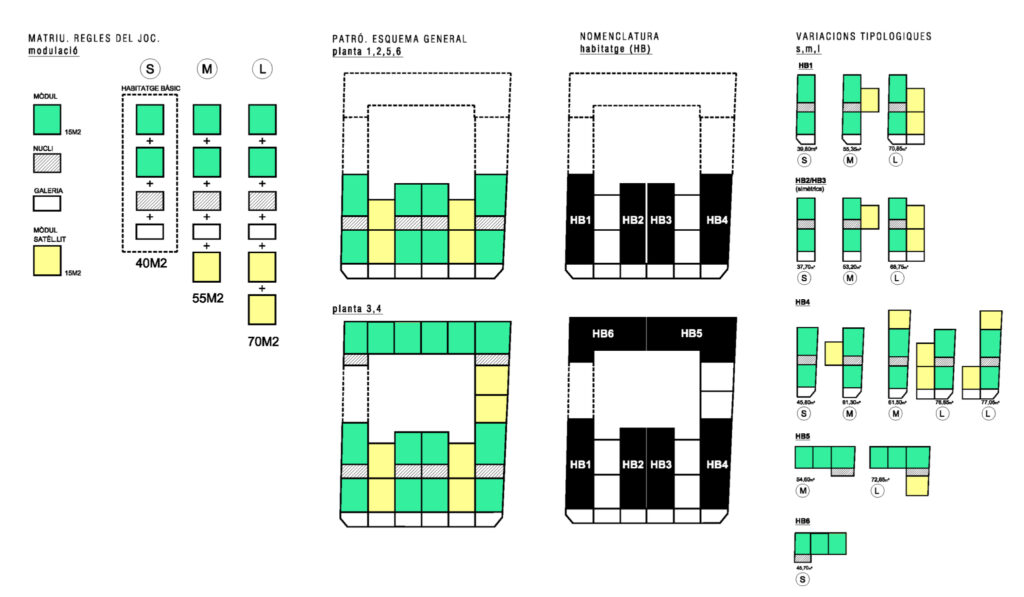

In addition to various public services, the versatile floor plans cater for the people of different generations and cultural and social background. As a result of a dialogue between five architecture offices, altogether 370 flats featuring 170 different layouts were created, with the cluster flats of Building A standing out in particular. Unlike conventional apartment buildings, they include not only private flats but also shared areas providing spatial abundance and areas for common activities. The cluster flats accommodating around 12 people feature spacious shared kitchens, dining and living rooms. Around the common areas, there are private flats (each equipped with a kitchenette, toilet and shower). In addition to the cluster flats, the ground floor also includes a workshop for people with disabilities. The cluster flats may be considered the spatial interpretation of cooperative buildings in Zürich.

The development is not only concerned with creating housing, but also actively integrating the public and residential spaces into the neighbourhood. This is emphasised by the focus on the area between the buildings, including communal gardens, playgrounds, sports facilities as well as areas for gathering, eating and socialising. The project combines activities through various cultural and educational programmes encouraging interaction between the residents and the wider community, thus contributing to the overall vitality of the area. Conscious inclusion of such programmes in residential developments could help to create socially inclusive and coherent living environments in Estonia too.

The affordability of the housing which is 20–30% below the market price and ensures access to more diverse user groups similarly speaks for the Zürich development project. Such collaborative models have a lot of potential to create inclusive communities, who prioritise the well-being and independence of their residents, while also contributing to the general development, sustainable urban planning and design of the city.

A case study:

La Borda, Barcelona, Spain

Plot: municipal land provided by the city to develop the cooperative

Developer: La Borda Housing Cooperative

Funding structure: 2,7 million euros

– Credit cooperative Coop57

– Participatory bonds

– Inhabitant contributions

– Loan from a commercial bank

Price: 840 €/m2 (20% lower than the market price)

Architecture office: Lacol

Authors: Arnau Andrés Gallart, Eliseu Arrufat Grau, Ariadna Artigas Fernández, Carles Baiges Camprubí, Ana Clemente Granados, Eulàlia Daví Borrell, Cristina Gamboa Masdevall, Ernest Garriga Vallcorba, Mirko Gegundez Corazza, Lluc Hernández Torns, Laura Lluch Zaera, Pol Massoni Mangues, Jordi Miró Bover, Núria Vila Vilaregut

Completed: 2018

La Borda cooperative was established in 2012 as a result of two factors. Firstly, there was a major housing crisis resulting from the economic crisis, unemployment and reduced salaries. Secondly, a strong neighbourhood movement had emerged in the region of Can Batlló in Barcelona, whose members were convinced, that in order to make housing more affordable, its development should rely on some other economic model not based on the free market economy.

Can Batlló is a former industrial area, which lost its vitality during the economic crisis. The city council of Barcelona encouraged the local movement Recuperem Can Batlló to take the initiative and reshape the area. After the nudge from the city to establish the organisation, several profitable businesses and public space solutions appeared in the district receiving media coverage accompanied by general public attention and interest. By 2016, the organisation had involved over 300 people in 35 ongoing projects. One of their greatest endeavours was the establishment of La Borda Housing Cooperative.

Residents as the housing developers

The cooperative’s bottom-up approach resembles the Andel model: a non-speculative economic model in which housing is a human right, not an exchangeable good in the market. The originally Danish model is a non-profit cooperative (andelsbolig in Danish), that brings its members together as the developers and managers of their housing. Each member is entitled to a housing unit in the cooperative as long as he continues to be a member. Membership is usually ensured by a payment proportional to the surface area of the home.

The construction of the La Borda building could be started thanks to the community’s self-sustaining and self-operating approach. The residents of all 28 apartment units were included in the design and construction process either working on the construction or organising the development. As typical to any development, the main problem lies in funding. The initial construction budget was 2.7 million euros, being well above the capabilities of Coop57, the main financier of the La Borda project. Eventually, Coop57 contributed 42% to the project, with 29% covered by participatory bonds and 29% by La Borda’s own funding (including the inhabitant contributions).

Residents assumed the role of the developer and the project manager. By applying the economic model that meets their needs, the result of the joint effort is not only a functioning but also a successful cooperative. La Borda exemplifies the most important aspect of the project is a strong community, allowing to save money and increase awareness of the project’s social value . Thanks to shared environmental-friendly beliefs, they managed to optimise the building layout, abandoned the idea of an underground parking lot, grouped the services (for instance, a common laundry room) and reduced the surface area of the façade. Also, recyclable CLT was selected for the load-bearing structure, making La Borda the tallest building with a wooden structure in Spain.

La Borda with its joint management logic was the winner of the Mies van der Rohe Award for emerging architecture in 2022. According to the jury, the key to earning respect in the architectural scene was the model of co-ownership and co-management forming the basis for the architecture.

Summary

In order to keep the future of housing bright, efforts should be directed to community-oriented projects such as La Borda or Mehr Als Wohnen. In Estonia, and particularly in Tallinn , there are no affordable housing policy principles and neither the city nor the state is in the habit of allotting plots or properties that could become the seeds for such projects. However, the given case studies show that a nudge by the public sector is essential for the emergence of such ventures. Once the mentality is shifted towards joint action, it is also possible to find space for alternative and sustainable ways of living. By shifting the focus from speculative investments to non-profit models, Estonia could tackle the root causes of the housing crisis and provide the citizens with the rights they deserve. This, however, requires new organisations and groups who would take on such projects.

In the examples above, a decisive role was played by the economic and inclusion models, which oppose the traditional public or private economic approaches. In the case of community models, the future tenant is clear from the beginning and thus also included in the design process. Albeit taking more time in the design stage, the project will be considered more thoroughly and the building will meet the user’s wishes better.

ENELI KLEEMANN is an architect practicing in Tallinn. She is one of the founders of the architecture practices Kollektiiv and Õu.

HELENA RUMMO is a PhD candidate at the Estonian Academy of Arts. She is one of the founders of the architecture practice Õu.

HEADER: Urban density in Hunziker Areal in Zürich. The neighbourhood was developed by a consortium of more than 30 cooperatives. Photo by Florian Rothenberger

PUBLISHED: Maja 113 (summer 2023), with main topic Housing