I believe that many a reader will imagine islands in the form of a curled-up coastline—after all, often there is little else there besides sea foam and bird screeching. Although Estonian islands are slowly growing in size, we still have a very large number of small islands—reefs, rocks, islets—whereas not so many islands where people would live all year round.

Lighthouse—a symbol for every island?

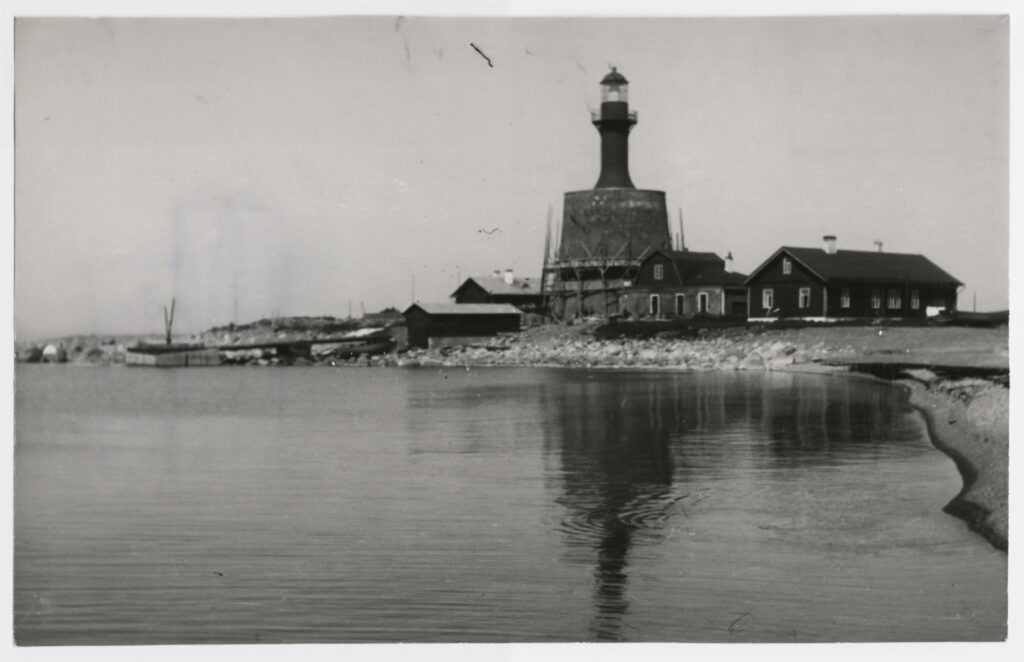

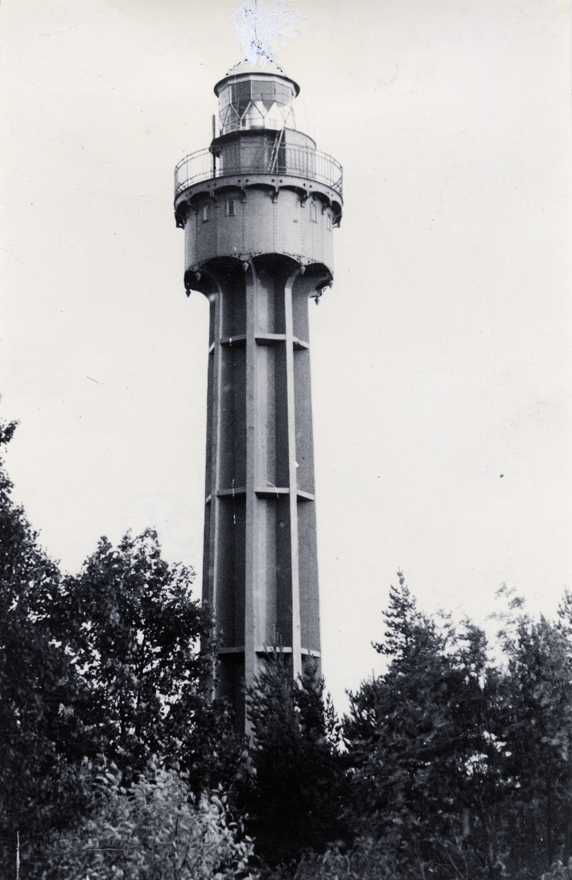

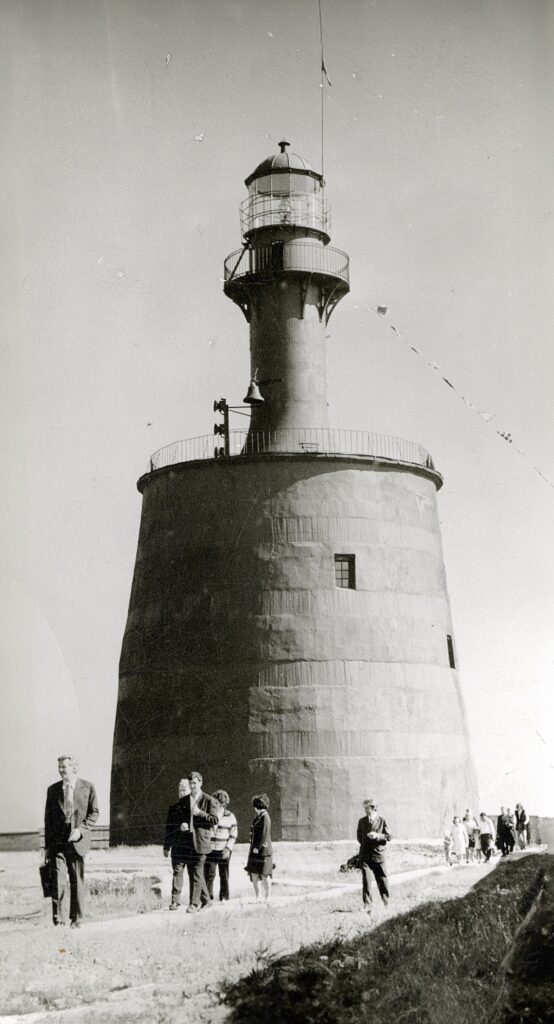

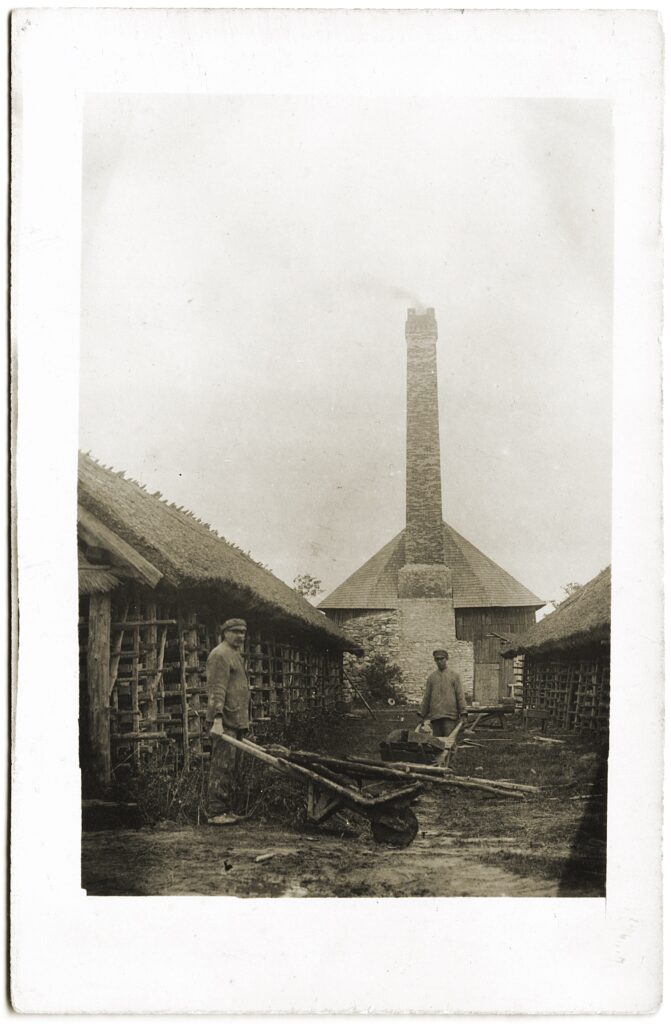

One of the symbols for almost every island is a lighthouse that has been built there. Islands, and especially those reefs, rocks and shallows that have yet to become proper islands, can make navigation perilous at times. Lighthouses and beacons are among the important facilities that give an early warning of obstacles on the way. While most lighthouses and beacons were erected on the coast, some also stand on mountaintops and hills, similarly to many churches. Construction of these towers was mostly a large-scale national undertaking—they were properly designed, and built and funded with an eye to modern technology.

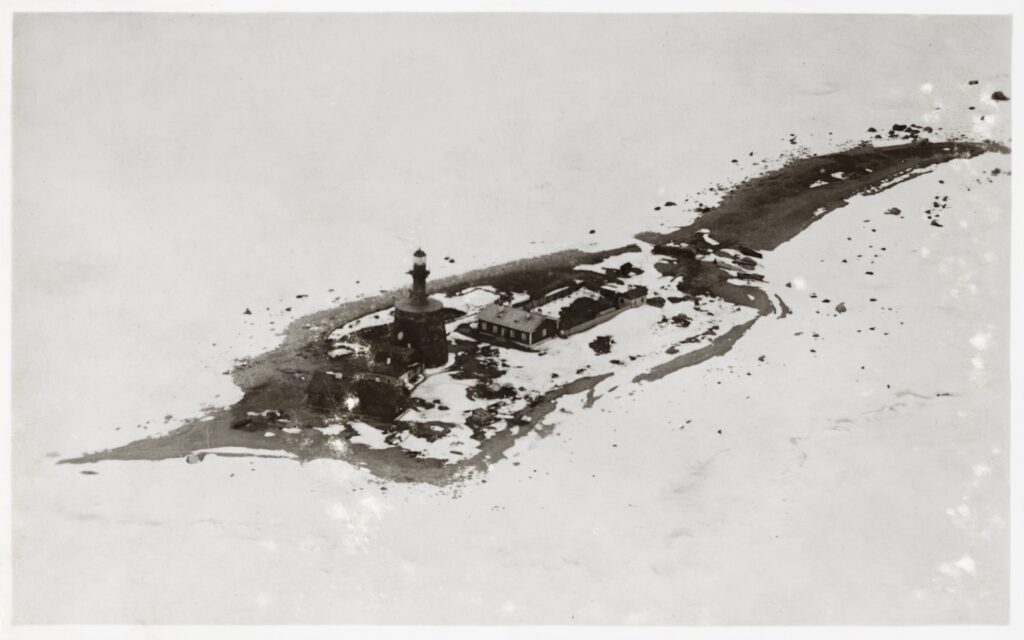

For the most part, the towers were not built with local materials; however, they were built with the help of local workforce. On some islands, lighthouse keepers remained the only residents, whereas in other places, harbours, villages and towns rose near the lighthouse. Think of our nearly 500-year-old Kõpu lighthouse—a fine piece of work whose light is still in operation today. The islanders of Hiiumaa have now also received a confirmation that their Ristna lighthouse was indeed designed by the very same construction engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose most famous tower stands in Paris.1 The construction of Keri lighthouse, however, has a legend attached to it—allegedly, Russian emperor Peter I, when he was asked about the shape in which the Keri tower should be built, pointed to a decanter on the table. Such famous names and legends, however, excite and fascinate mainly those who are coming from inland. For seafarers, the crucial thing is the light, and also the colour and shape of the tower.

On some islands, lighthouse keepers remained the only residents.

How does the sea make island homes special?

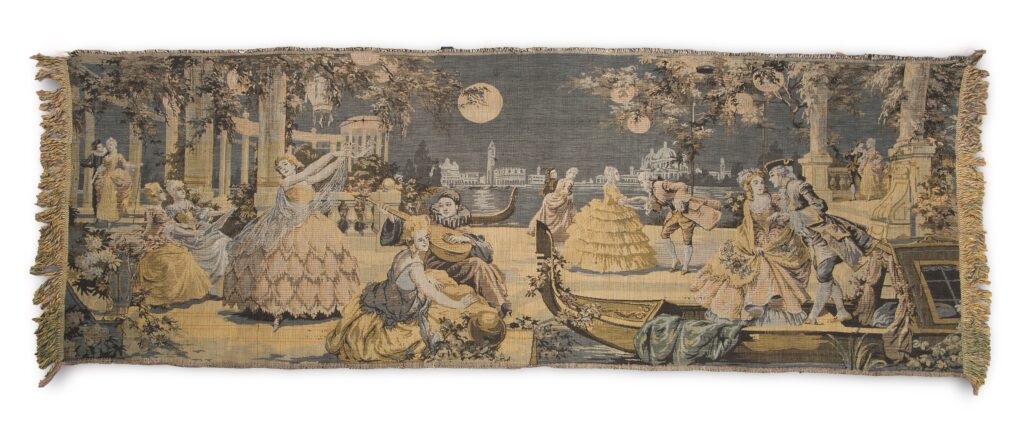

I have often found myself thinking that islanders are like some tentacled sea creatures that grab new things from here and there, and then quickly begin to make them their own. I have a vivid memory of how visitors from the mainland who came to my childhood home could not help but wonder at our broad two-person rocking chair. I myself in turn wondered whether all these adults had really never seen a rocking chair before. I did not know then that in Estonia, this sort of rocking two-seater was made only in Hiiumaa. Probably all the sea trips to Finland had given someone the idea, and after the first one had been built, it started to spread quickly. All local men were able to do woodwork in those days, and this is how that type of chair became a thing of their own. Less is known about the wooden sofas that were also widespread on the island, but there is a nice quote from an old coastal dweller’s recollection about a shipwreck in 1869 on the coast of Hiiumaa: ‘Oh dear, that’s when a lot of treasure started washing ashore; the waves began to break the chambers on the top of the deck; the beach was littered with ship pieces, velvet sofas, silk pillows, blankets, chairs and all sorts of valuable things; […] People nearly drowned themselves; they couldn’t wait for the sofa to reach the shore, but raced into the sea, only to get their hands on those silk pillows’.2 The materials used for building houses likewise often came from the sea—beams and boards that had washed ashore. The tapestry and pictures that hung on people’s walls more often depicted camels and lions than foxes and wolves. Coastal folk were always anxious to get out to the sea and beyond the sea, from where everything that they desired could be brought back to the island as gifts. Some signs like that used to suggest and still suggest that you are looking at the home of a true coastal dweller.

How and where to live on an island?

Thinking of Estonian islands a hundred and plus years ago, many of them got quite empty during summers, for many young folk sought employment on the mainland or on ships and did not stay at home. When winter came, all the heated rooms were once again filled with people. Today, islands have become summer resorts, and the most important things for the city folk who come there are warm seawater, forest and the opportunity to retreat from their everyday lives. While in earlier times, almost all people on a smaller island knew each other, now there is so much back-and-forth traffic that the great ‘kinship of islanders’ is disappearing or dissolving. Life is becoming more self-centred and less dependent on one’s neighbours. Mari Möldre mentions a rather similar phenomenon when describing the emergence of corridors, which began appearing in residential buildings from the late 16th century onwards.3 Separation of rooms creates privacy. The same thing has happened in many island homes that offer summertime accommodation for friends and relatives. Many such country houses are now surrounded by a field of booths where guests are sent to sleep. This speaks of the hosts’ desire to achieve and maintain at least some privacy.

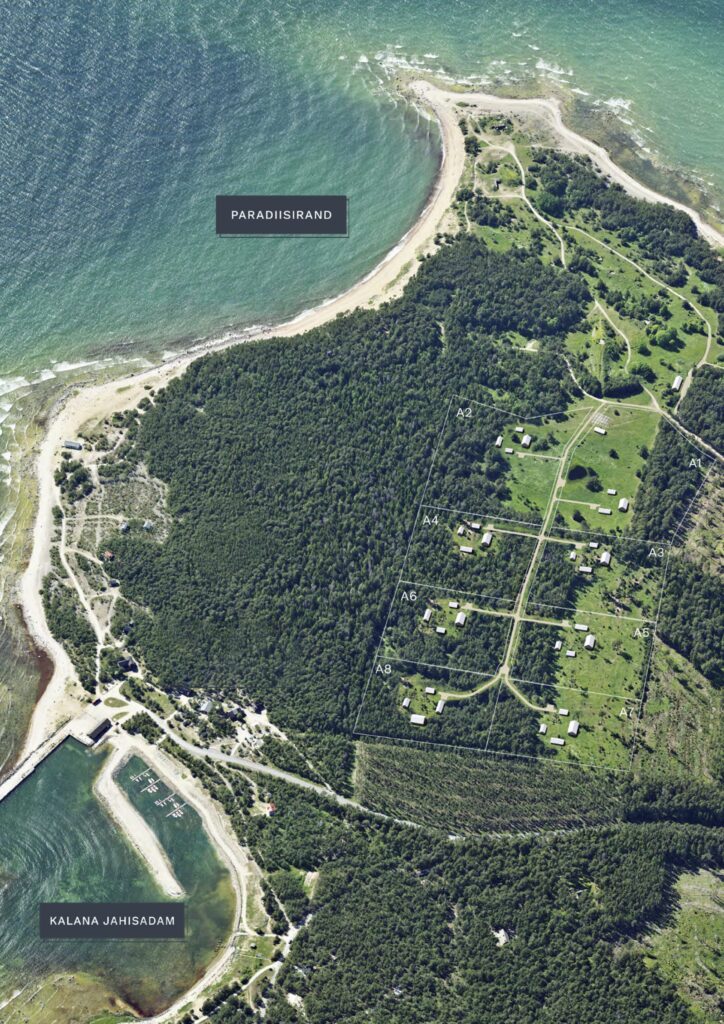

Back when our islands began to receive their first summertime visitors, the latter lived in either local people’s homes, schoolhouses or pastorates—in simple and scant conditions. Here it is good to recall Voldemar Panso’s stay on the small island of Kassari, where, after moving out of a schoolhouse, he was able to find lodging in the hayloft of a local woman named Lepa Anna. There was no grumbling about it, for simply being able to spend your summer on an island that had been declared part of the restricted border zone back then was in and of itself a luxury. Quite a lot of vacant farmhouses became available after the Second World War, which saw a significant part of islanders fleeing across the sea. The first summer arrivals who bought these houses gradually assimilated into the community—they bought eggs, butter and milk from their neighbours, and also brought something from the city in return. Many artists paid the villagers who replaced the roof tiles of their old houses with specially made thank-you-paintings; writers did the same with books. Natural economy remained in place, houses were made liveable using simple means, and the relationships with the local folk were natural. Surely there is still some of this around, but what we see more often on the islands today are wondrous and expensive new developments. Alongside the simple living and long traditions of the natives, new micro-communities that distance themselves from the locals and have their own security systems and internal rules are increasingly gaining ground. 9–10 adjacent plots in the forest or at the seaside go on sale, and soon after, costly houses pop up. Although the latter are mostly meant for spending summer vacations, the buildings themselves can be substantial. The buyers are looking for places of special natural beauty rather than local people. In case these houses are ever sold on, they are sold to buyers with similar purchasing power.

Beautiful vacant villages

When I visited the German island of Sylt, I was driven through several gorgeous old villages. All the houses were magnificently restored, true to the era, and in a good shape. There were very few people around because it was not quite the season. I soon found out that almost all of these houses belonged to rather wealthy owners from the mainland, who visited the island only for one or two months in the summer and perhaps also during Christmas. For the rest of the time, the windows stayed dark and security cameras were switched on. In fact, there were no locals there anymore, or perhaps only in one or two farms on the edge of the village. And young people complained that they were no longer able to buy real estate on the island because prices had become unprecedentedly high. The permanent population of the island was rapidly declining, and it was thought that soon, almost everyone who works there will commute from the mainland. At the same time, jobs are steadily disappearing, because there are simply too few permanent residents, and most of the summer spots close for the winter.

On the other hand, many summertime visitors wish to see islands as a kind of preserve of the olden days, whether it be in the sense of buildings or ways of life. Holidaymakers’ desire for the old often helps to preserve time-honoured value better than permanent residents do, because for the former, these buildings are not simply outdated family dwellings, but a romantic legacy of island life. A holidaymaker will proudly show you their restored barn-dwelling and several tens of centimetres wide authentic floorboards, whereas a local would be ashamed beyond belief for not having been able to progress past the 19th century.

What to ask from an island, who to protect and from whom?

People have also always been drawn away from islands, whether it be due to poverty, overpopulation, remoteness of markets, or simply dreams of something else. The beginning of the 21st century has brought along an outflow of islanders, and not only in Estonia. The same problems have plagued Bornholm, Gotland as well as several other islands in the Baltic Sea already for decades. Jobs disappear or are lost, young people move out to cities, there are insufficient quotas or fishermen to do proper fishing, large-scale production is toned down—similar problems occur everywhere. Life is changing so fast and islands have not always been able to keep up, or have not always wanted to paddle along. Should they quickly adopt the norms of urban life, then, or are there some other models out there?

In the late 1980s, several Estonian islands became part of the West Estonian archipelago biosphere reserve, the activities of which are today directed by UNESCO’s Man and Biosphere programme. This means that on these islands, various educational, cultural and scientific means are employed to value and preserve the traditional interaction between nature and people.4 The consumption-centric condition was supposed to give way to something new that would put equal value on both nature and man. Years have now passed, and we are in a position to assess how much did it help that with the creation of biosphere reserves, the islands could have more say in regional planning. Toomas Kokovin, who wrote on these matters extensively in 1992, found it especially bad when local economy stops relying on local nature and materials sourced from it. As a consequence, traditional skills begin to fade away and a general mental deterioration sets in.5 These values are now being collected and written into the UNESCO intangible cultural heritage list.

The creation of biospheres in and of itself did not increase the population of islands back then, but it did lead to a better understanding of topics that are now being heatedly discussed, such as climate change and loss of biodiversity. Today, it seems that we are once again at a kind of turning point—people have begun to notice the value of living in the countryside, and have started to move there again. The islands are no exception.6 What are the needs of today’s arrivals? We know that these include comfortable living conditions, fast internet, stable transport connections, etc. There is no doubt that changes in how our work is organised, whether it be in the city or in the countryside, will also change life on the islands. Well-organised transport has brought islands ever nearer to the mainland. The charm and distinction of remoteness and reclusion is disappearing.

Do people move to the island after a pleasant summer vacation experience, or do they do it in order to look for their roots? Both, I suppose. Can long dark periods on a windy patch of land compete with cities full of cafes, cinemas and people? Is a small village school able to provide education of sufficient quality? These kinds of questions are being asked by newcomers again and again. Is it the case that the more there are arrivals, the faster will the changes come, and we can no longer talk of sustainable development and a local skills-based way of life? On the other hand, we know already from history that islands have always been frequented by outsiders, and local islanders have always been longing for what is new and exciting. What will be the ratio of permanent residents and summertime holidaymakers? How will the line between longing for the new and longing for the old be drawn? Should the new be somehow based on the old, or should it rather be only brand new? Does it matter at all? In any case, islands need to have space for pristine nature, views of the sea, gusts of wind, natural light and darkness. What else?

HELGI PÕLLU is an historian, ethnologist and Research Director at the Museum of Hiiumaa. Her area of specilisation is the cultural history and heritage of Hiiumaa.

PUBLISHED: Maja 114 (autumn 2023) with main topic ISLANDS

1 Indrek Laos, ‘Ristna Eiffel’, on the webpage ristnaeiffel.ee, May 1st, 2017.

2 Pavel Lepp, ‘Viie miljoni eest varandust merepõhjas Hiiu Kalana randas,’ in Nad tegid toad tuule pääle, elud ilma ääre pääle, ed. Helgi Põllo (Kärdla: Keskkonnainvesteeringute Keskus, 2002), 51.

3 Mari Möldre, ‘Hot Bath and Cold Deal: Living Space’s Two Faces,’ Maja 113 (Summer 2023).

4 Helgi Põllo, ‘Life on the Island. Fire, Water, Air, Earth,’ exhibition text of the permanent exhibition of Hiiumaa Museum.

5 Toomas Kokovkin, ‘Hiiumaa areng ja loodushoid’, in Hiiumaa eripära ja arengusuunad, ed. Ruuben Post (Kärdla: Haapsalu Trükikoja Kärdla trükikoda, 1992), 36–37.

6 Tiit Tammaru, ‘Linnaelu ei meelita enam sedavõrd kui vanasti,’ Maaleht, October 5, 2023.