It is no news to architects and real estate developers that the design of a new spatial environment usually begins with parking spaces as if it was the fundamental value. More and more practitioners, however, complain about the outdated mindset related to parking norms and the need for a new approach allowing to implement more sustainable decisions. Tartu city architect and the head of the spatial design department Tõnis Arjus discusses the city’s new ambitious online app considering the parking spaces according to the actual need.

The functioning of the society depends on the balance between man and his environment. The way we use land and what rules we set on it will also determine the quality and daily life of our future space. According to the Estonian Human Development Report1 and Eurostat analyses2 Estonia is one of the countries where land take for human activity at the expense of natural environment and agricultural land has been extremely rapid and the amount of inhabited land per person is one of the highest in Europe.

The given trend cannot be taken as an inevitable part of development. It is the result of continuous, more or less conscious activities supported by laws, standards and also attitudes shaped by opinion leaders and politicians.

The sustainability of spatial evolution and reasonable land use are particularly problematic in the development of cities as numerous functions need to be handled in a small area of land. This makes even minor decisions highly important and, thus, it is mandatory that normative documents are up-to-date. Standard EVS 843:2016 with the parking norm for buildings is one of such basic norms.

Parking as an extensive use of land

The impact of parking on the living environment and people’s behavioural patterns has recently become a popular topic. And rightfully so. It is a highly space-intensive use of land. At the same time, the number and location of parking spaces also has a clear impact on the growth of car use pursuant to the classic logic of supply and demand. Decreasing the supply in the urban space is a complex political decision. However, the latest amendments to the above-mentioned parking standard have taken the spatial development of the Estonian cities to regression. In order to avoid making such difficult decisions in the future, wise choices must be made now.

The parking norm is peculiar for two reasons. First of all, it is featured in a standard (available for a fee) giving recommended guidelines. Yet, the given document largely defines the development of our cities and many details may become a decisive factor in the creation of either a better or worse spatial solution. The guidelines given in the standard will lose their recommended character once the municipalities make it mandatory in their comprehensive and detail plans. This is where the guidelines become a fundamental principle from which there must be no deviations.

The second curiosity is the amendment made in the standard’s latest revision in 2016. It considerably increased (with no analyses or justification) the required number of parking spaces for buildings. If earlier, there had been regional differences for the centre, intermediate zone and suburbs, then now regional differences were diminished with the central area as the only exception where the parking norm is the lowest (i.e., in case of lack of space, the standard number of parking spaces is not required).

As a result, when planning an apartment building, up to 50% more paved areas must be established than so far and the number of parking spaces per flat is the same for all regardless of their location in a suburban or denser urban environment. In a situation where the use of every square metre must be carefully considered, it is an acutely premature decision that has been questioned by planners, developers as well as residents.

Data-driven approach

In order to confirm the need for updating the parking norm, the city of Tartu commissioned an analysis of two completed development areas to assess the actual use of the parking lots. It appeared that the occupancy of parking lots remained below 100% also under the earlier and more lenient parking norm, even if counting the additional cars in the street. Also another problem transpired: parking lots often remain half-empty because the spaces sold to particular flats may not be in constant use but as the spaces are designated, they cannot be used by anyone else either.

The given tendencies are confirmed also by recent debates on parking, highlighting repeated situations where people have been forced to acquire a parking space even if they don’t need it. However, the parking spaces have not been established based on the market demand known to the developer but due to the given standard as its compliance is required by local governments. Thus, the principles of the standard are founded neither on the national strategic goals of stopping the growth of and reducing car use nor (even more surprisingly) on the actual need. As a result, we have urban spaces where the increased motorisation is welcomed by the growing parking lots, and in the long run, it is clear that nature abhors a vacuum and the forced supply will increase also the demand.

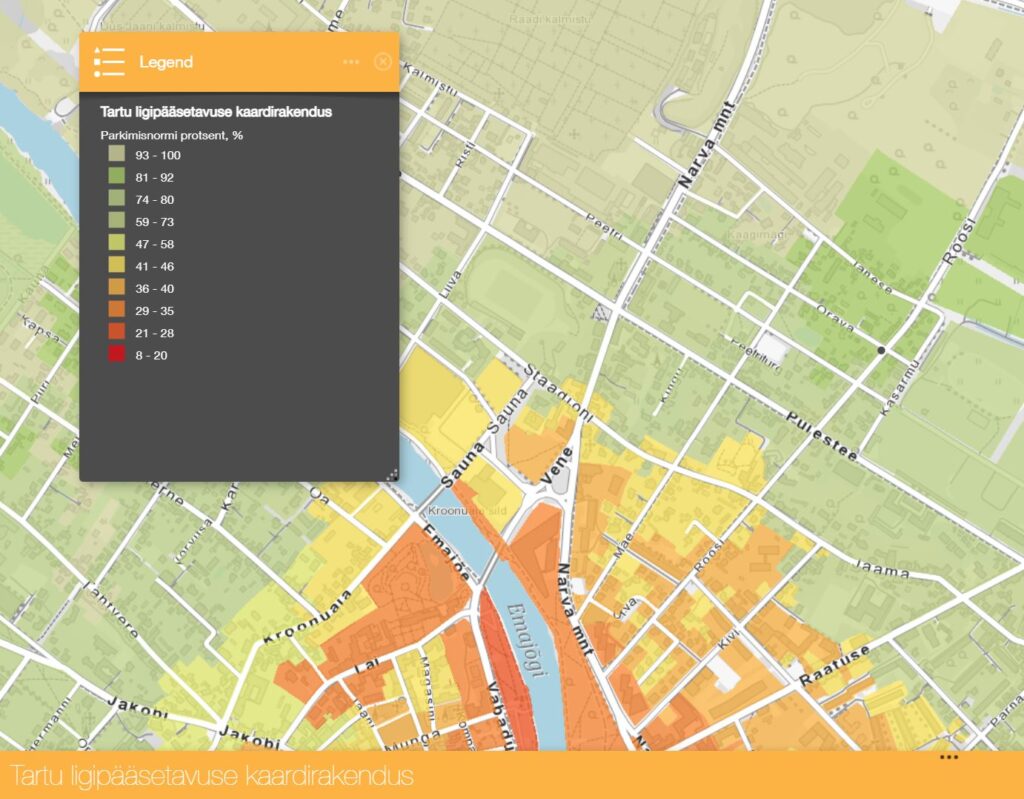

Instead of looking for an alternative for the standard, the city of Tartu decided to develop a data-driven system that does not cancel out the standard but provides a tool for making decisions on the basis of site-specific requirements. It is not a final solution to a complex problem but an important step in the direction of smart planning.

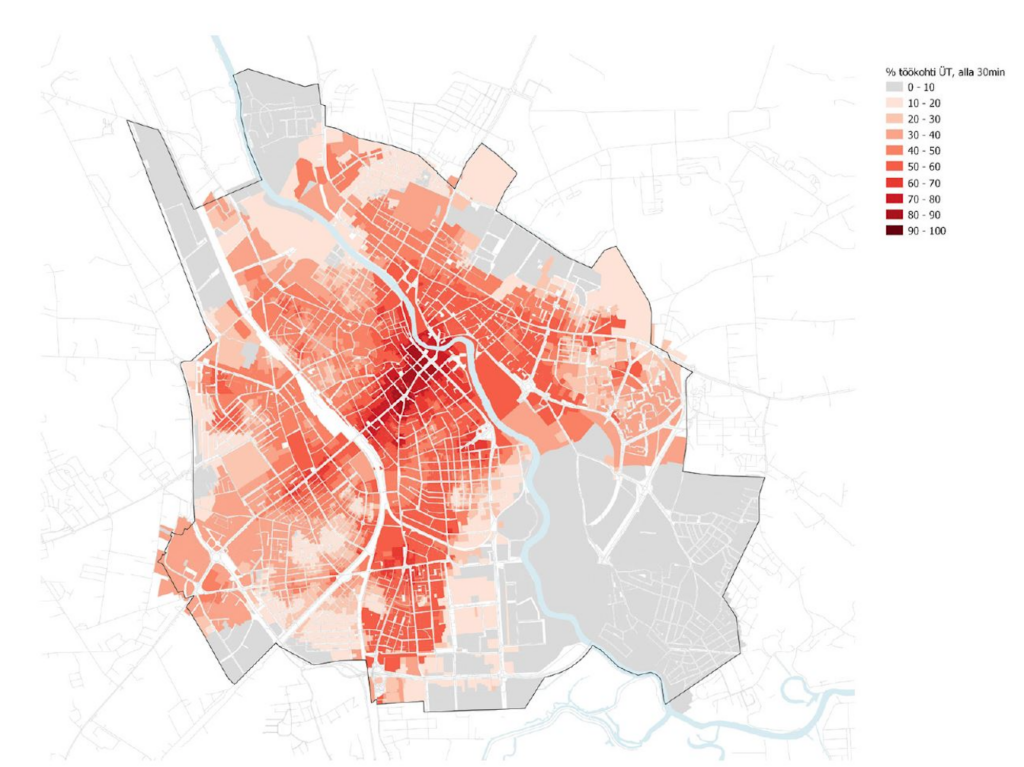

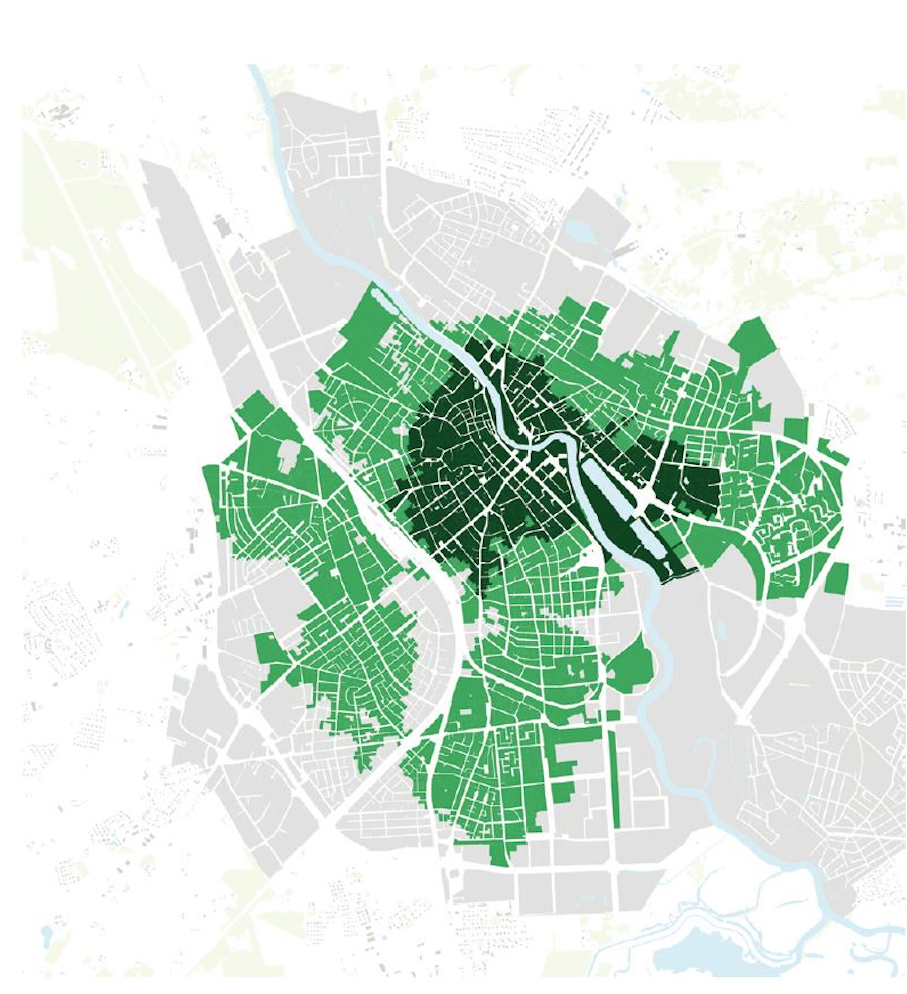

In the new system created by Inphysica technology,3 it was decided to tackle three main issues:

- To evaluate the accessibility of properties located in the city to work, educational institutions, service providers, shops, restaurants on foot, by bike and public transport.

- As a result, to determine the current central area where the parking standard applies as the highest possible value.

- To determine the recommended number of parking spaces for each property pursuant to their accessibility indicator.

The output included an online application with a much wider function than determining the number of parking spaces for developments. It is a good tool for home-buyers who wish to get an overview of the nearby schools or shops. It is also useful for planners in evaluating which services are lacking in the area and therefore also in greater demand.

The need for new applications

The app has its obvious limitations and we will continue working on its improvement. For instance, at the moment it ensures an overview of the current situation while planners and developers would be primarily interested in the evaluation of future developments. Thus, when planning new services and jobs, we need to know the new housing planned in the area.

Therefore, further work needs to be done to integrate the information of comprehensive plans and construction rights of valid detail plans and to create decision-making tools supporting the planners and developers in conducting smart and diverse planning activities. Similarly, it is important to continue increasing the data collection area for the application including also the neighbouring municipalities. Residents do not really care about the exact location of the municipality borders, however, the location of services and people’s homes must be in a logical sequence. The information provided by the app is of interest not only to the residents of Tartu but all urbanised areas.

Force of habit

All in all, it is important to raise awareness of the mechanisms shaping our environment for the worse from both human and natural aspects. It is often a matter of long-term habits with their accumulative effect not assessed and not intended to be assessed. There are many similar activities in various regulations, institutional activities and budget policies that are not based on intricate conspiracies but purely on the force of habit. Considering the global and local context and the severe setbacks caused by the lavish development on the individual and state level, we must gradually continue the inventory of regulations and move towards smarter means.

TÕNIS ARJUS as been the city architect of Tartu for the past 10 years and led the new spatial design department for 1.5 years. His work is focused on the development of cities exploring the possibility of sustainable cities under the current conditions.

HEADER: Zeppelin Shopping Centre in Tartu. Photo: Rein Urbel

PUBLISHED: Maja 111 (winter 2023) with main topic Street Unrest

1 Tõnu Oja, “1.1 Changes in Land Use: Distortion of the meaning of urban and rural“, Human Development Report 2019/2020. Spatial Choices for an Urbanised Society (SA Eesti Koostöö Kogu, 2020), ed. Helen Sooväli-Sepping, https://inimareng.ee/.

2 „SDG 11. Sustainable cities and communities: Estonia“, SDGs and me — 2022 edition, Eurostat (2022), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/digpub/sdgs/index.html?country=EE&goal=SDG11&ind=5&chart=bar

3 Parkimiskohtade vajaduse määramine Tartu linnas, by Inphysica Technology (2022) https://tartu.ee/et/uurimused/parkimiskohtade-vajaduse-maaramine-tartu-linnas