The coastal line in Tallinn with its versatile length of 46 kilometres could turn the capital into a genuine seaside city, especially when considering also the proximity of the Old Town to the sea. However, the general perplexity predominating in the years of Estonian independence has left the coastline in the city centre a curious obscure and characterless wasteland. The painful consequences of the lack of a clear vision have affected the users and owners of the space as well as the city government directing the planning. The seaside visions undertaken this year may have tangled a little, however, once again at least the direction is right – to open Tallinn to the sea. If only there was no asphalt on the way…

The Sea, the City and History

According to the long-standing city architect of Tallinn Dmitri Bruns1, the connection between the city and the sea was destroyed in the early 20th century when Kalamaja was cut off the coast with the harbour and industrial constructions with the eastward extensions of the harbour expanding over the whole coastal area in the city centre. The international comprehensive plan competition in 1912 was won by Eliel Saarinen, however, the main drawback of the work lay in its lack of contact with the sea: the city turned its back entirely to the sea while the harbour was declared a closed area. Neither was realised the plan to establish a cargo harbour on the east coast of Kopli Bay in 1916 to stop the extension of the present harbour and thus prevent the destruction of the only part of the coast open to the city. Consequently, the seaside town tradition was broken and has not been recovered ever since.

Since the Soviet period or the first comprehensive plan of Tallinn in 1952, the priority has been given to Tallinn as a seaside city, at least in word. The second comprehensive plan or the Great-Tallinn project delineated a city developed towards the sea while emphasising the importance of the incongruous seaside arterial road passing the city centre. The idea of a seaside park was retained with the elongation and straightening of Mere Avenue, in other words, creating access to the sea. The aim of the competition for planning and housing the city centre of Tallinn in 1972 was to move the cargo harbour to Paljassaare and open the expansive maintained coastal area by joining the parks surrounding the Old Town up to Kadriorg. In 1984, the connection of the centre and the city was suddenly dropped with another version of the city centre detailed plan. According to Bruns, ever since the second half of 1950s, the emphasis shifted to solving the issues related to functional structure, traffic and technical indicators leaving the composition and aesthetics of the urban design plans – architecture as art – at the background.

In 2007, the city council again approved the concept “Opening Tallinn to the Sea” with one of its aims including a populated urban space. The simultaneous activities – seaside arterial roads and the wire fences obstructing the sea views and the use of the coast, however, were entirely contrary. The sea view should not only be enjoyed from the car window of the residents of Pirita and Viimsi or the truck driver’s cabin on their way to the harbour.

Space and Traffic

Bruns’2 optimism in the article in 1963 reflects the logic of the day with the rapidly increased number of vehicles and the exhausting road capacity solved by the construction of new arterial roads. In late 1970s an unexpected voice is heard3 claiming that in terms of urban design it would be better to keep pedestrians on the ground while the vehicles are taken into tunnels or onto overpasses. The quote of the time sounds surprisingly contemporary, “Finding a solution to the given problems is not the task of traffic specialists only, instead, the process should be actively and consciously participated also by architects-urban designers. It is only the unanimous cooperation that allows us to create a new living environment and only hope that it will not be criticised too severely by the next generations.” It is similarly admitted already then4 that “the most efficient means against the abnormalities stemming from the increasing number of cars is the prioritisation of the mass transportation of passengers, the electric transportation in particular, as well as the considerable improvement of the ride quality, speed and regularity”. Separate bus lanes are stipulated already in the 1977 transport development complex scheme together with some other quite innovative ideas that have still not been realised.

Several old, yet pioneering ideas have remained incomplete and only on paper, making it all the more curious that the construction of extensive arterial roads rooted in the planning ideology of the 1960s is implemented with meticulous care and upheld in all comprehensive plans with no wider discussion up to the most recent comprehensive plan of Tallinn in 2001 and the comprehensive plan of the coastal area between Paljassaare and Russalka in 2004. At the Tallinn II Urban Forum in 2010, it could only be stated5 that “our understanding of good quality of life in a city nevertheless stands for a versatile public space and density allowing happy meetings. Unfortunately, the given contemporary shifts in focus relying on human and environmental reasoning do not yet find reflection in the transportation system in Tallinn”. With the excuse of reducing congestion, which is always pleasing to the voters’ ear, the idea of sustainable transportation and human-centred approach have been conveniently abandoned.

The sustainable development strategy of Tallinn city area (2015) laden with formulaic slogans commits to providing the residents of Tallinn by 2020 with a human-friendly and environmentally sustainable public space integrating various forms of mobility while the development supports the reduction of automobile dependency by means of more convenient public transportation, pedestrian and cycling lanes and more pleasant public spaces. It is stated in the development plan of Tallinn (2013) that population increase is enhanced by the improvement of the quality of life of urban residents which primarily stands for further focussing on the needs and wishes of the residents. Not a word is said about the prioritisation of vehicular traffic that, however, is seen and felt in the daily urban environment. Directing heavy traffic outside the city centre is a slogan with long history, suitable for selling anything including asphalt and inconvenient arterial roads that cannot be crossed by pedestrians, yet are paradoxically located in the city centre.

Although the first steps towards drawing up the prescribed comprehensive travel plan have been taken, it seems that the city government wishes to overtake the results of the research and implement the colossal investments with irreversible spatial changes (also to the city centre coastal area) without adequate informed knowledge. The written promises to make the city government’s planning activities more knowledge-based and strategic sound highly ironic, as do the declarations to increase the role of participatory democracy and the transparency and substantiation of the decision-making processes due to public interest – the public has recently witnessed only shameful haste, impressive evasiveness, and the concealment of documents and information when both Haabersti and Reidi road cases were “made public”. It seems that the city government wishes to instruct by means of the simple rule, “Do as I say, not as I do”. Although it would require nothing more but taking all the nice development documents out of the drawer, sweeping off the dust and implementing them.

Infrastructure and Cooperation

According to the dictionary definition, infrastructure stands for the system required for the economic development of the region and the welfare of the society. For some reason, it has reduced to a mere synonym for pipes and highways. In common usage, infrastructure seems to be a symbol of construed happiness and progress (usually with asphalt and railings). The notion, however, has become obsolete, as the social development in the 21st century has come to underscore other values and indicators – softer, more versatile and on a human scale.

In their concern for the buildings, pipes below and above the ground, asphalt and anonymous planning, the present Estonian urban planning and (local) government authorities have forgotten people. The main tasks listed in the introduction on the website of Tallinn Transport Department do not include people, pedestrian or cycling lanes. The responsibility of the City Planning Department is to ensure the residents a good quality of living, including the management of the city road network planning. As the head of the City Planning Department responsible for the management of the development, the city architect chooses to remain silent and kindly allows the activists to suggest alternatives, in other words, do the work of city officials and commissioned planners free of charge.

The various road construction projects vividly reveal the dominating unilateralism arising from excessive focus on (road) engineering. The separation of road planning from city planning illustrated by the separate respective authorities in all cities is absurd. While the infrastructure development is mostly conducted in the engineer’s office, the new urban landscapes call for integrated solutions.

The reason for standardised infrastructure and the universality that does not suit everywhere lies in cost reduction, while, in fact, the multifunctional infrastructures (i.e. in addition to the instrumental value, also the communal dimension such as the flood control channels as cycling lanes) have proven to yield more long-term social, aesthetic and environmental benefit. This is where architects come in6.

Road construction project teams must include specialists of other areas such as (landscape) architects and urban designers. The space between the buildings and the public space, in other words, any urban design relations are in their area of responsibility and competence that would be dangerously unwise to ignore.

With the industrial revolution, also technological networks became fetishized products7. The novelty and innovativeness of the infrastructure concealed social power relations and became desired objects of their own as symbols or visions of a better future society. Technology was no longer an instrument and such an approach persists to this day. The operative and economic role of infrastructure is generally valued while the cultural, ideological, social and aesthetic role is usually left unnoticed. The eternal debate on the supremacy of and borderlines between architecture and engineering should wind down to creating synergy – everybody contributes to the creation of space and the wider the horizons and more diverse the experience, the more qualitative results could be expected. It is particularly important with respect to infrastructure because it is not a mere linear object for transporting energy, vehicles, communication etc, but a real and physical public space. Even if it happens to be underground, its impact is perceived on the ground in the form of protection zones and restrictions thus directly influencing the urban space (position of buildings, trees, green areas etc).

The Vision of the City Centre Coastal Area

In winter 2016, the Estonian Centre of Architecture, Estonian Association of Architects and the city of Tallinn organised a vision competition with the aim of establishing a basis for turning the coastal area into a contemporary human-centred urban space and drawing up a vision document regarding the spatial relations in the coastal area.

Based on the motivation letters, the three working groups came to include Kavakava and Linnalahendused, KOKO Architects, Linnalabor and Mareld Landskapsarkitekter. Following the presentation of the sketches prepared for the public urban forum, two teams continued with the suggestions in cooperation with Tallinn City Planning Department and Centre of Architecture condensing the spatial principles of the coastal area and principles for the implementation of the visions as well as outlining the further processes (action plan). Due to the misunderstandings in the final stage, the work has now stalled as if hanging in the air. Despite the optimism expressed by the city architect regarding the implementation of the ideas and even the employment of a specialist coordinating the seaside area, it will probably be highly difficult to take any real action during the pre-election period.

The aim of the vision proposed by Linnalabor and Mareld Landskapsarkitekter (Elo Kiivet, Martin Allik, Kadri Koppel, Regina Viljasaar, Teele Pehk) is to enhance the well-being of people through the seaside space and ensure the activity in the area already before the implementation of the developments. The vision was based on the concept that the seaside area is an object of increased public interest and its development must be open and public. A key role in the activation of the entire area is played by connections forming a clear network of open spaces (including a green network). The key connecting device of the seaside area is a promenade that could be varied (construction at various pace) and in continuous development (from temporary/inexpensive to more permanent) but it must be uninterrupted (both physically and temporally) and meet the needs of people moving at varying pace. The principles of the promenade apply to all landowners to the full extent of the seaside area with the requirement that they first need to construct the promenade or access to the sea. As the entire area is massive, it could be developed in continuous stages while the spaces could be kept alive with intermediate land uses by creating public spaces also with temporary solutions. The aim of intermediate use is to experiment with various practices to enhance or maintain the identity of the place, create new destinations, increase the property value and generate a positive image. The tools here include a bureaucracy-free experimental space, toolkits for activating the coastal area (paints, brushes, building material, outdoor furniture, street art etc), call for ideas, information point etc. It should be remembered that it is a continual non-linear process. It is only with the consistent implementation of the developments and highly broad-based publicity activities and participation that a happy seaside area could be ensured.

The solutions proposed by Linnalabor are placed on a biaxial scale of time and space (temporary vs permanent, easily executed vs time-consuming) and thus instruments suited for the occasion and possibilities may be selected from the toolbox suggested in the vision proposal. The process could begin with the organisation of events, extension and widening of beta-promenade and the establishment of a temporary experimental space. The participants in the preparation and realisation of the seaside vision include the respective working group, a participatory designer (a project manager working on the vision at the city government ensuring the consistency of the process, much like the 20 cooperation officials at Helsinki City Planning Department), intermediate use curator (e.g. Kalasatama Temporary) and the compiler of the wider plan. It is important to include specialists of various fields (architect, urban designer, planner, landscape architect, communication or inclusion specialist, as well as specialists of environmental technology, management of environment and ecology).

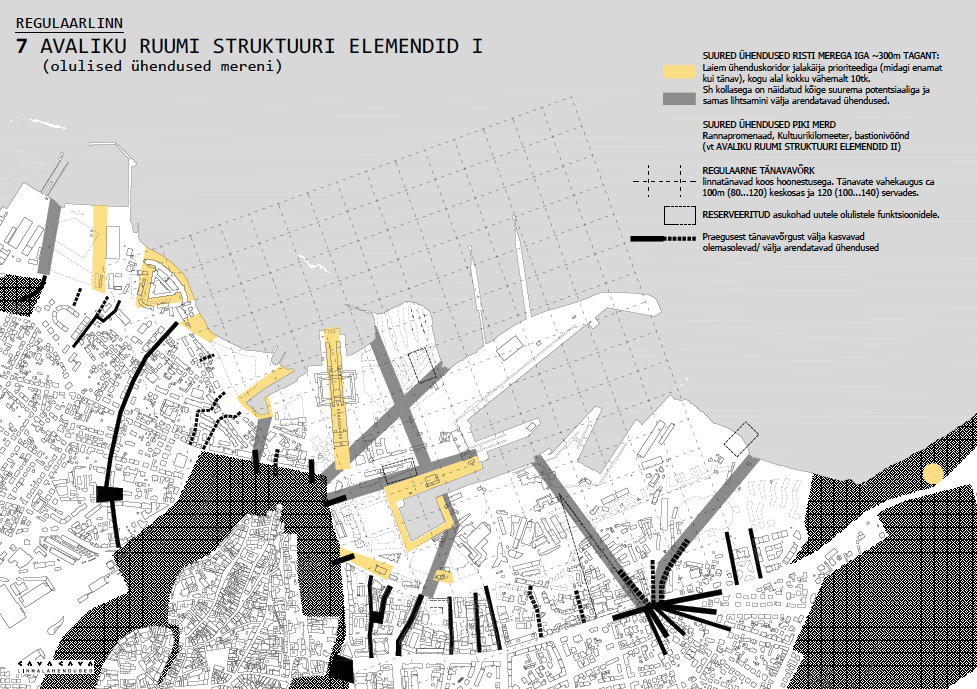

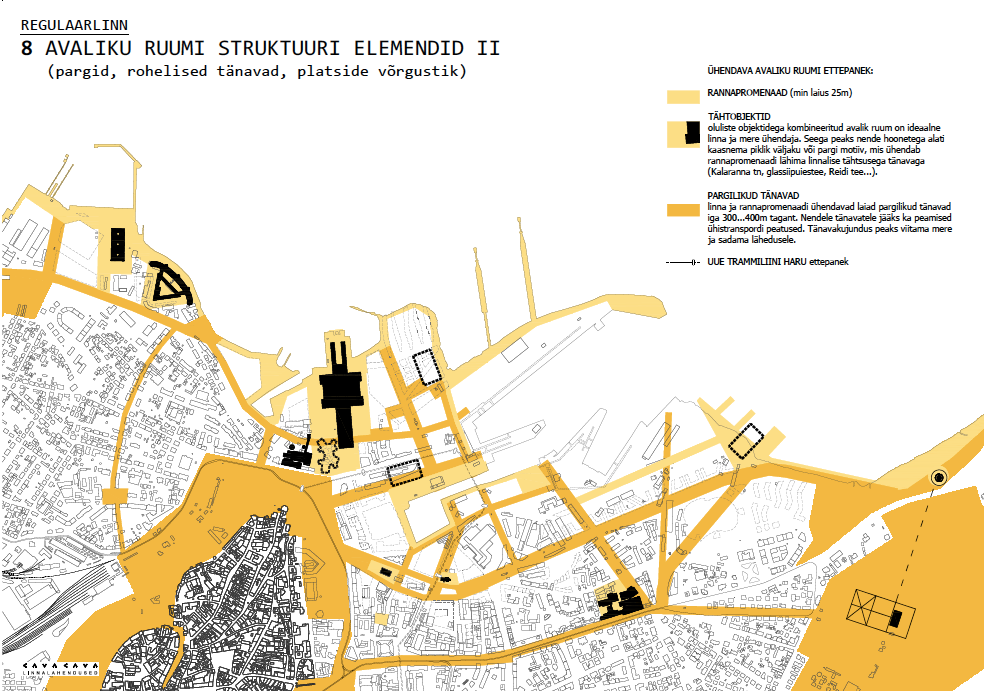

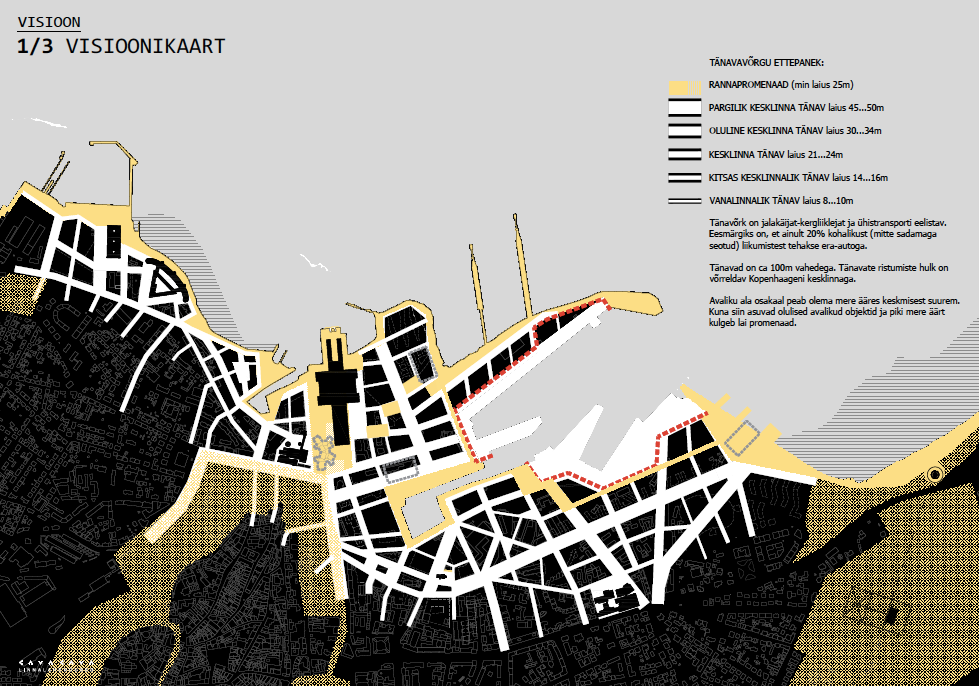

The proposal by Kavakava and Linnalahendused (Siiri Vallner, Indrek Peil, Kristel Niisuke, Toomas Paaver, Renee Puusepp) highlights the drawbacks of the present situation: the seaside is low in density, yet marked by barriers, it is random, yet not free, coastal, yet separating the city from the sea. The work is based on the urban elements of Tallinn founded on local geography: the varied coastal line (temporary flooded area, sandy beach, pier, canal), various dominants (city hall, Patarei sea fortress, the Creative Hub and new reserved areas of significant local importance), centrally located harbour as an important part of the city’s identity (requiring further integration into the urban space). The core of the work lies in establishing a dense and regular road network with inner-city quality. It also includes the construction of new access passages and breaking through the present detailed plans that generate encapsulated spaces.

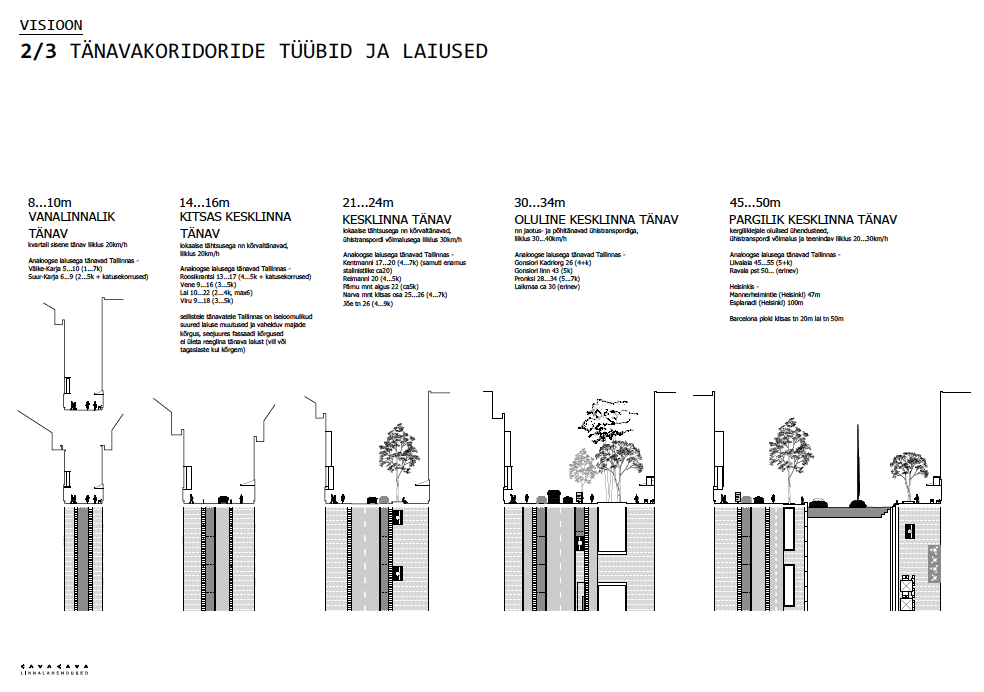

In their improved version, Kavakava compiled an illustrated street space manual with street corridors of various type and width. The new regular road network (connected with the general city network) forms a framework for the emergence of inner-city diversity which with the green network will connect the seaside promenade with the bastion belt and Kadriorg Park. There will be about 50 new streets crossing with the sea, at least 130 intersections, 70 new quarters and 27 kilometres of new built-up street fronts. In the long run, the realisation of the vision would require stability and firm leadership of the city, clarity and transparency. Temporary experiments could function as a testing ground for possible solutions.

On the basis of the proposals by Kavakava and Linnalabor stressing various facets of the vision, Toomas Paaver additionally prepared a draft proposal for the city council considering also the ways to tackle the challenges of the realisation of the vision. The proposal for a decision for the approval and realisation of the seaside city centre vision of Tallinn attempts to bring together the results of various working groups and urban forum workshops (in 2009 and 2016) in the form comprehensible to officials and readily available in practice, setting out the initial principles prior to the preparation and completion of the “big plan” (whether a structure plan, comprehensive plan or else).

Ideals and Ideologies

Paraphrasing Ahto Lobjakas8, it may be said that urban planning will not disappear but rather become increasingly instrumental and operational, cliquey and political. “But liberalism will disappear as will its central load-bearing beam meliorism or the idea that life can be improved – the thought has no real content without universalism and idealism. Anything will be possible, both good and evil. The truth is the right of the strongest.” The city architect admits9 that he cannot aim for the ideal. But how else could a city be developed? The word “meliorism” reflects the vital faith of any stakeholder participating in strategic, spatial or other kind of planning and the improvement of urban life – a conviction that living conditions will improve or they could be improved as a result of human effort. In case the given faith is replaced with cynicism or inaction, nothing good could be expected. Planning a city or creating a space without idealism and personal visions/activity would mean remaining stuck in the past and allowing the forward-looking vision of seaside Tallinn to wane.

In the absence of great ideas and ideologies, a question arises if the replacement of the pressure to build Soviet communism with the rush to catch up with the West followed by the emptiness resulting from the consumer tedium inhibits us from using any “programmes” or striving for ideals? Are ideals considered a disgrace that cannot be fitted in Excel spreadsheets or practical indicators such as GDP? How could the “soft and subjective” concepts, i.e. concepts without unambiguous meaning used by architects and planners compete with numbers and lofty slogans?

Treating the communication disorder rooted in the weight of various “arguments” and overcoming the standstill would require more bold, competent and proactive officials to help the leaders of the city to make the right decisions. Or visionary leaders with a comprehensive view of the big picture and daring to deviate from the mainstream flow. Or truly functional and democratic cooperation between various parties of spatial design without superficial power structure. Just as it is not appropriate to contrast poets with physicists, the opposite of practical is not aesthetic or poetic. Tõnu Õnnepalu10 has cleverly pointed out that the forced opposition does not hold true, “Practicality is generally understood as usefulness / …/ Some say practical means easy to maintain, little effort. However, the noble old Greek word praxis means something thoroughly different. Experience, work, understanding. While the other Greek word at the root of poetry refers to doing, creating form and also working. It thus transpires that poetry and practice are relatively close concepts.”

Intermediate uses and cooperation (designers) are some of the possible means deviating from the conventional paths of city planning whether the borderlines of fields of activity or the planning processes stipulated in laws. Among other things, looking forward means that everything cannot be foreseen and some room should be left for freedom, improvisation and change of direction. Borrowing some lines again about the writer’s garden by Õnnepalu, “Poetry means that certain freedom, wildness, spontaneous growth is retained in the garden. So that everything would not be too pruned. Practice stands for the ways to achieve the given impression. As the wildness of a garden is not natural wildness much like freedom in poetry is not arbitrariness.” The path from vision to action primarily requires the courage to dream, selecting the ideal to strive for and finding the means to do it, even if the necessary tools have not been in use before.

It was stated by Triin Ojari already more than ten years ago11 that “today we could rhetorically say that after several architecture competitions and round table discussions, court cases and scandals with considerably fewer spatial choices left, we still have the opportunity to choose – whether to abandon the attempt to establish a communal centre at the coast for good or not. However, when leaving out rhetorics, we may admit that the choices made or not made have turned the harbour area bordering the city centre into peripheral virgin soil where the new sparse world of entertainment comes to form one of the numerous atopias suitable everywhere, a pseudo-city with no site-specificity”. Unfortunately, it must be admitted that the seaside has remained a cheapish commercial area marked by wastelandish sparsity. Then again, on the bright side, we still also have the opportunity to choose. The only question is who will assume the leading decision-making role in case the city government does not wish to or cannot do it.

ELO KIIVET is an architect and urban designer. She is a lecturer at Tallinn University of Applied Sciences, teaches architecture also at Tallinn Art Secondary School and works in Linnalabor.

HEADER image by Land Board of Republic of Estonia.

PUBLISHED: Maja 91 (autumn 2017) with main topic Shared Space

1 Dmitri Bruns „Tallinn. Linnaehituslik kujunemine”, Tallinn: Valgus 1993

2 Dmitri Bruns „Sinu linn, tallinlane”, Rahva Hääl 26.–27.09.1963

3 Tiit Metsvahi „Keskkond – linnaehitus – liiklus”, Sirp ja Vasar no 50, 16.12.1977

4 Reedik Võrno „Sõiduauto – liiklus – linnaehitus”, Sirp ja Vasar, no 45, 11.11.1977

5 Kaja Pae „Linnafoorumid. Urban Forums”, Eesti Arhitektuurikeskus 2011

6 „Infrastructure as Architecture. Designing Composite Networks”, editors Katrina Stoll, Scott Lloyd, jovis Verlag GmbH 2010

7 Maria Kaika, Erik Swyngedouw „Fetishizing the Modern City: The Phantasmagoria of Urban Technological Networks”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 2000

8 Ahto Lobjakas „Tõejärgne induktiivne oma(s)ilm”, Sirp 07.07.2017

9 Juhan Teppart „The conflict surrounding the Reidi Road project”, A short documentary accompanying MA thesis in Urban Design 2017

10 Tõnu Õnnepalu „Poeesia ja praktika”, Eesti Ekspress no 28 (1440), 12.07.2017

11 Triin Ojari „Tallinna teekond mereni”, MAJA 12.07.2006