As I was gathering my thoughts with regard to the connections between carbonate rock, time and buildings, I was reminded of a commercial building with dolomite end façades in Kuressaare at Tallinn hwy 16, also known as Ajamaja (House of Time). The intriguing and slightly enigmatic name allows for different interpretations and enticed me to approach the topic namely with an emphasis on carbonate rock buildings that are characteristic of their time. Every new construction era in the long history of our carbonate rock use has revealed new aspects of this material. Each era has its own zeitgeist and this enables us to speak of particular houses of time that represent the main eras of carbonate rock use.

The essence of carbonate rock

The importance of carbonate rock in Estonia is twofold. On the one hand, it is part of the primeval natural environment that surrounds us; on the other hand, it is simply a material that humans have used for their benefit for hundreds of years. These two roles are very closely connected. What was once retained in stone by the primeval sea now determines its properties and possible uses, which have not been definitively exhausted yet.

Carbonate rock has its own way of keeping time. This eloquent stone would not be here for us, if the current territory of Estonia had not been covered by sea ca 415–475 years ago in which various types of carbonates could sediment. 60 million years is a sufficiently long period for the sea to turn from cold to warm, from shallow to deep due to climate cycles. We know all of this thanks to limestone. Limestone had to lie ‘uselessly’ in the ground for hundreds of millions of years. Humans committed themselves to it only 600–700 years ago, when a need emerged to build structures that would offer shelter and security.

Carbonate rock is a general term for limestone, dolomite and marl. The intermittent climate cycles over the 60 million years of carbonate rock formation in Estonia are the reason why the stone consists of layers with different properties. The thickness of stone layers limits the building stone sizes that can be quarried, which could be from 50 cm up to 1 m depending on the stone, but usually stays within the range of 20–50 cm. Limestone is the most common type of carbonate rock. Chemically pure limestone contains 56% of calcium oxide (CaO) and 44% of carbon dioxide (CO2). Dolomite contains not only calcium oxide but also magnesium oxide (MgO). The chemical composition together with structure and texture determines the decorativeness and all other properties of a carbonate rock. Fossil-rich carbonate rock is especially striking due to its colours and patterns.

Thinking about carbonate rock as a building material, we should proceed from the words of structural engineer Hubert Matve: ‘The quality of a limestone building depends on the possibilities hidden in the stone and mastery of the craftsman.’ These hidden constructional possibilities stem namely from the composition, decorativeness, porosity, water absorbency, pressure tolerance and cold-proofness of the rock—properties that differ in each type of carbonate rock. For instance, when limestone turns into dolomite, the chemical composition of the rock changes, and hence, the fossils and layers disappear—from a constructional perspective, this means that it becomes a stronger and more uniform material.

Medieval houses of time

We still have plenty of carbonate rock in the ground. In order to study what it can offer us today, however, it is useful to take a step back and familiarise oneself with the properties of the most important carbonate rock types and earlier examples of their use. For this purpose, let us place them on a timeline, which lets us discover new possibilities in otherwise well-known types of constructional carbonate rock.

Carbonate rock use in the Middle Ages was special and unique. Different regions of Estonia saw the emergence of different local (and later on more widely used) types of carbonate rock, which were turned into significant buildings that bore the stamp of their time. Thus, we can speak of medieval houses of time, in which the type of carbonate rock used had a great importance. These types of carbonate rock, each with its own constructional properties and distinct appearance, form the basis of all the later eras of carbonate rock use. Around ten types of carbonate rock have proven themselves suitable for high-quality construction work with their centuries-long dignified history of use. 7–8 of them still remain intermittently in use.

Greenish gray, massive and easy-to-process Kaarma dolomite was representative of Saaremaa in the Middle Ages. Saaremaa’s aforementioned House of Time, built in the early 2000s, was likewise finished using Kaarma dolomite, thus continuing a centuries-old choice from a time when Kaarma dolomite became the prime natural building stone in Saaremaa. It is quarried in Kopli farm quarry and larger Kaarma quarry, both in central Saaremaa.1,2 An example of a medieval house of time built of this stone is Kuressaare Episcopal Castle, where almost everything is made of Kaarma dolomite. This castle is also where limestone was declared the national stone of Estonia on 23 April 1992.

With the construction of Haapsalu Castle, another carbonate rock-built medieval house of time, Ungru limestone came to the fore. It is a fine-grained limestone, the colour of which ranges from grey to yellowish grey, and the thickness of layers ranges from a couple of centimetres to 60–70 cm. This is Estonia’s most decorative stone, which is quarried in Pusku and Sepaküla quarries in Lääne County.

The spirit of the era of monks lives on in the Vasalemma ‘marble’ of Padise Abbey in western Harju County, a material for masonry as well as carving. This limestone, characterised by a whitish grey shade, good workability and marble-like structure, consists of cement and the stem joints of echinodermata. Vasalemma stone formed in the Ordovician (450 million years ago) in a subtropical bioherm zone. Although the supply of Vasalemma stone is limited and the area where it can be found is small, this decorative carbonate rock was still used to mass-produce crushed stone in the Soviet period. The strength of this stone depends on the cementation level of the particles, and it can happen that a solid- and massive-looking stone begins to crumble when exposed to the elements, which is why it should not be used beyond interior conditions without thoroughly studying it first.2, 3

The carbonate rock building material that has withstood the test of changing times and adapted to them the best is Lasnamäe construction limestone—platy, clearly layered (with a layer thickness up to 30 cm) and easily quarriable. This stone, which was the main building material in Tallinn throughout the Middle Ages as well as later on, has its vivid texture due to ruptures created by sedimentary gaps, and due to brownish bulge-like traces of organisms that once lived on the seabed.2,4 This type of limestone is made especially striking by frequent petrified nautiloid shells. Lasnamäe construction limestone is available from Pakri islands in Harju County to Tallinn and all the way up to Narva—there is a lot of it. The limestone consists of 56 layers that have very different properties and have to be extracted layer-by-layer if they are to be used in construction. Some of the layers are superbly weatherproof, while others do not last even a couple of winters.

Lasnamäe limestone suited well for tile carving (stairs, terraces, portals, gravestones, etc.), whereas for more plastic kinds of carving, much more suitable Märjamaa stone began to be used in Tallinn already in the 14th century. This type of stone is today known as Orgita dolomite and it has a special status among other types carbonate rock. It is the best—most massive and most hewable—carving material found in Estonia. This greenish, bluish or yellowish-grey dolomite, with layers up to 70 cm thick, formed in the Silurian (408–439 million years ago) from clayey dolomite mud that sedimented in the laguna zone of a tropical shallow sea. In the medieval Old Town of Tallinn, many houses as well as museums retain a lot of carved details made of Orgita stone—ornamental window frames of churches, lintels of interior portals, window pillars, coats of arms, etc.

Paide Order Castle gave fame to whitish grey and finely porous Paide dolomite, which began to be quarried for the castle in Kureküla, today a part of Paide town.2,3 Only a couple of quoins remain in the castle ruins, but the stone was so good that it was used also in limestone-poor Viljandi to give form to a building with the richest carvings in the Middle Ages—Viljandi Order Castle. Two very important and presentable types of carbonate rock come from Lääne-Viru County—Borealis limestone and Röa dolomite. Borealis limestone, also known as ring limestone, consists of 50% of Brachiopod Borealis borealis shells. The medieval house of time for this type of carbonate rock is Vao Castle. Greyish yellow dolomite of Röa member got its name from Röa quarry in Rapla County. This type of carbonate rock is found in a narrow zone across Estonia from Lääne County to Virumaa. Finally, a single variegated complex of limestones and dolomites can be found between Sillamäe and Narva—so-called Narva limestone, the colour of which varies from grey to green to red to violet to brown shades.2,5 The medieval house of time representing this stone is Narva Hermann Castle.

Post-medieval houses of time

Later on, virtually no new types of carbonate rock were adopted in construction, although the methods of use for the known types were updated and modified. One could observe individual cases of a certain type of carbonate rock coming into prominence, depending on the current zeitgeist, type of building and suitability of rock type. Getting stone from more distant quarries was no longer an obstacle.

Some of the most noteworthy examples of houses of time are surely provided by turn-of-the-20th-century industrial architecture in and around Tallinn, in which Lasnamäe construction limestone is the protagonist. The nature of this stone, including its platy and suitably thick layers that are easy to work in both horizontal and vertical directions, enables to create imaginative masonry and decorative details. If the quarried layer is properly chosen, Lasnamäe stone withstands industrial loads very well.

Architects in the newly-created Republic of Estonia were also fond of using carbonate rock. In Herbert Johanson’s rich architecture, Lasnamäe limestone was most prominent, and the architect was well aware of the possibilities it harboured. Herbert Johanson, Alar Kotli as well as Edgar Johan Kuusik loved to combine various types of carbonate rock known in Estonia—they were able to mix and match Lasnamäe limestone, Kaarma dolomite, Vasalemma ‘marble’. At the time, the state subsidised the extraction of Vasalemma ‘marble’, and it was used to build the presidential office, parliament building, and Oru Castle. Something similar to the early Estonian architects’ awareness of possibilities within different rock layers and their ability to combine them eloquently can also be witnessed in one contemporary house of time—the Kumu museum building, in which Finnish architect Pekka Vapaavuori found a way to simultaneously use Lasnamäe limestone, Kaarma dolomite, Orgita dolomite and Ungru limestone.

From the Soviet period, not a single building deserves the title ‘house of time’, because even though Kaarma dolomite was widely used in the form of decorative slabs, the work had a very low quality—tiles were processed poorly and anchored to the walls with corrodible materials. The only remaining construction stone quarries in the Soviet period were indeed in Saaremaa; elsewhere, quarries switched to producing crushed stone. This sort of negligent attitude towards stone and its possibilities was one of the motivators for establishing the Union of Estonian Limestone in 1992.

With the second coming of the Republic of Estonia, three houses of time designed by Raine Karp—Linnahall, Sakala Centre and the National Library—led to a limestone renaissance. Given the lack of Lasnamäe limestone—construction stone was no longer produced in Tallinn and everything extracted was turned into crushed stone—these buildings utilised variously processed Tagavere dolomite from Saaremaa. It is unfathomable to this day why Sakala Centre was not put under heritage protection so it would not be barbarically torn down for commercial purposes. How the stone from the demolished building was used is also not publicly known. At the very least, it could have been turned into crushed stone.

Surely there are other contemporary houses of time, albeit more miniature ones than the aforementioned examples. Kaali Visitor Centre and Angla Heritage Culture Centre, established by Saaremaa entrepreneur Alver Saguri, put the spotlight on a hitherto lesser-known type of carbonate rock—massive and very promising Selgase dolomite. Compellingly textured Ungru limestone has also made a comeback; its fine texture is further enhanced by the varying colours of its layers—grey, yellowish, black. Gildemann OÜ is extracting Orgita dolomite, turning it into products by using modern methods, including lathes and other machine tools. The same stone is also used to produce decorative tiles and construction stones that have a pretty pastel shade. Use of decorative tiles and details made of Kaarma dolomite and Lasnamäe limestone has also continued. Decorative ring limestone has been rediscovered by enterprising OÜ Põhjakivi that produces various carbonate rock details and polished decorative tiles. Dolomite from Röa member in Inju, which had already been forgotten, has now by readopted by HM STONE CO OÜ, led by Hillar Müür.

Photo: Gennadi Baranov

What next?

A house of time representative of our days should implement well-known types of constructional carbonate rock that have the best physicomechanical properties. The precise ways for implementing them should be decided by structural engineers and architects—the history of carbonate rock use provides some guidance. There are also tens of purely decorative types of carbonate rock; we only need to find suitable places where they could be quarried. We should also continue to combine different types of carbonate rock, and also brick, wood and rubble in striking ways.

There is no need to worry that extracting carbonate rock for construction purposes results in an excessive footprint in nature—rather, we should worry that there are plans for the near future to extract senseless amounts of construction stone, including very high-quality stone, in order to produce crushed stone for Rail Baltic. Sections of quarries are extracted for crushed stone in full, paying no heed to the alternating layers with good and poor constructional quality. This concerns especially Lasnamäe limestone, in case of which no one is bothered to sort out such high-quality construction stone layers as the so-called white and grey archine or the ‘ristikord’ bed. Quarries that produce crushed stone cannot be simultaneously or later on used for quarrying construction stone, because blasting creates microfractures in the rock. However, construction stone can indeed be quarried at least 200 metres from a former crushed stone quarry, as microfractures do not reach that far. One example of this is Rummu quarry—after crushed stone production ceased at the site, a carbonate rock quarry was established on its edge.

Old carbonate rock quarries are part of cultural heritage and good places for landscape architects to redesign them into recreational areas

Old carbonate rock quarries are part of cultural heritage and good places for landscape architects to redesign them into recreational areas, as it was done with the southern quarry in Lasnamäe. In addition, they are very important sites for geological studies. There are many carbonate rock quarries in Estonia (Vasalemma, Harku, Lasnamäe, Kalana, Reinu, Kaarma, Ungru etc.) that function as destinations for geological tours to study rocks, fossils and stratigraphy. Writing about limestone, we cannot ignore its nature as our national stone. This stone is our bedrock, a symbol of Estonian being and persistence. ‘Inscriptions in stone are for the waves to choose’, writes Olivia Saar, thus poeticising our limestone. How much we value these inscriptions is for us to choose.

HELLE PERENS is an Estonian geologist. She is the author of the four-volume monograph series Paekivi Eesti ehitistes [Limestone in Estonian Buildings] and has published numerous articles on limestone.

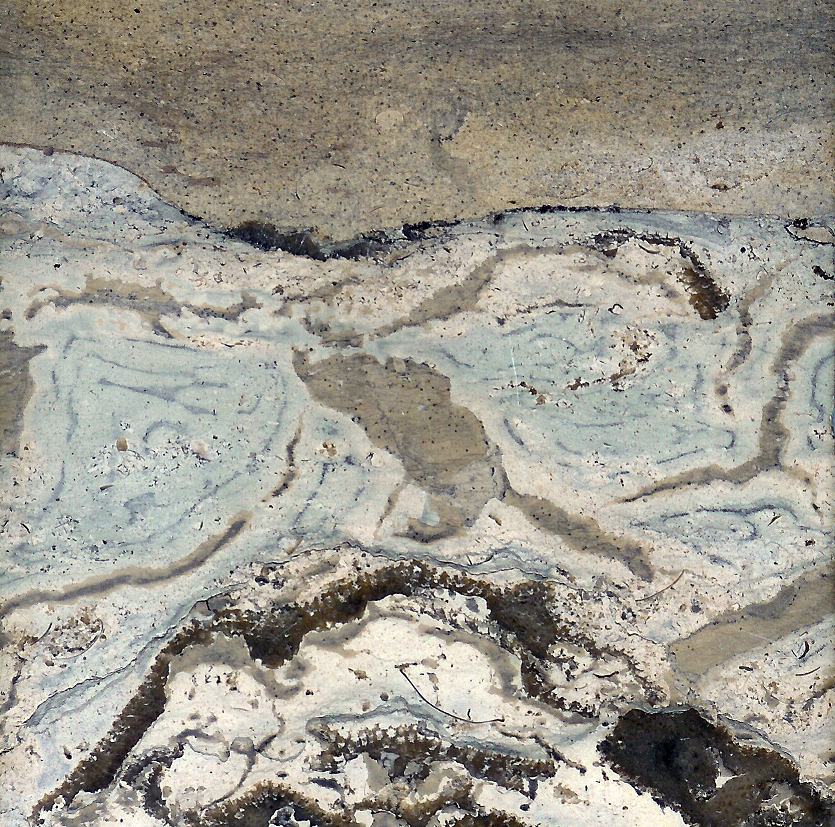

HEADER: Ungru limestone in Ungru Manor. Photo: Helle Perens

PUBLISHED: MAJA 1-2024 (115) with main topic STONE

1 Helle Perens, Paekivi Eesti ehitistes I. Üldiseloomustus. Lääne-Eesti (Tallinn: Eesti Geoloogiakeskus, 2003).

2 Helle Perens, Looduskivi Eesti ehitistes (Tallinn: Eesti Geoloogiakeskus, 2012).

3 Helle Perens, Paekivi Eesti ehitistes II. Harju, Rapla ja Järva maakond (Tallinn: Eesti Geoloogiakeskus, 2004).

4 Helle Perens, Paekivi Eesti ehitistes IV (Tallinn. Eesti Geoloogiakeskus, 2010).

5 Helle Perens, Paekivi Eesti ehitistes III. Lääne-Viru, Ida-Viru ja Jõgeva maakond (Tallinn: Eesti Geoloogiakeskus, 2006).