KASUDAGAI CENTER CENTRE

Architecture: Chie Konno (teco)

Location: Aikawa, Kanagawa, Japan

Built in: 2022

Site area: 1508m2

Built area: 820m2

Floor area: 1131m2

Structure: newly built timber-frame structure

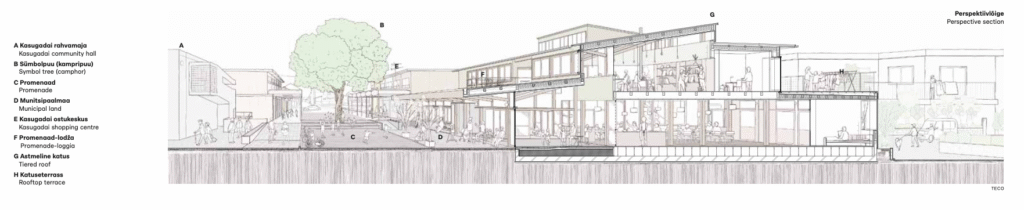

Programme: a multifunctional building with care, community, and gastronomic functions

A Building As a Form of Care

Japan is, statistically speaking, one of the most elderly societies on the planet, with approximately thirty percent of the population over the age of 65.1 This is due to a number of factors, the main one being a series of baby booms during a period of rapid economic growth after the Second World War, followed by several decades of low fertility rates. As these baby boomer generations retire and require additional assistance, the demands that they place on urban environments are also shifting: barrier-free or low-barrier spaces, proximity to medical and social care, new forms of living to provide informal support structures. The aging population requires nothing less than a radical retooling of the territory, with architects and urban planners at the forefront of this transformation.

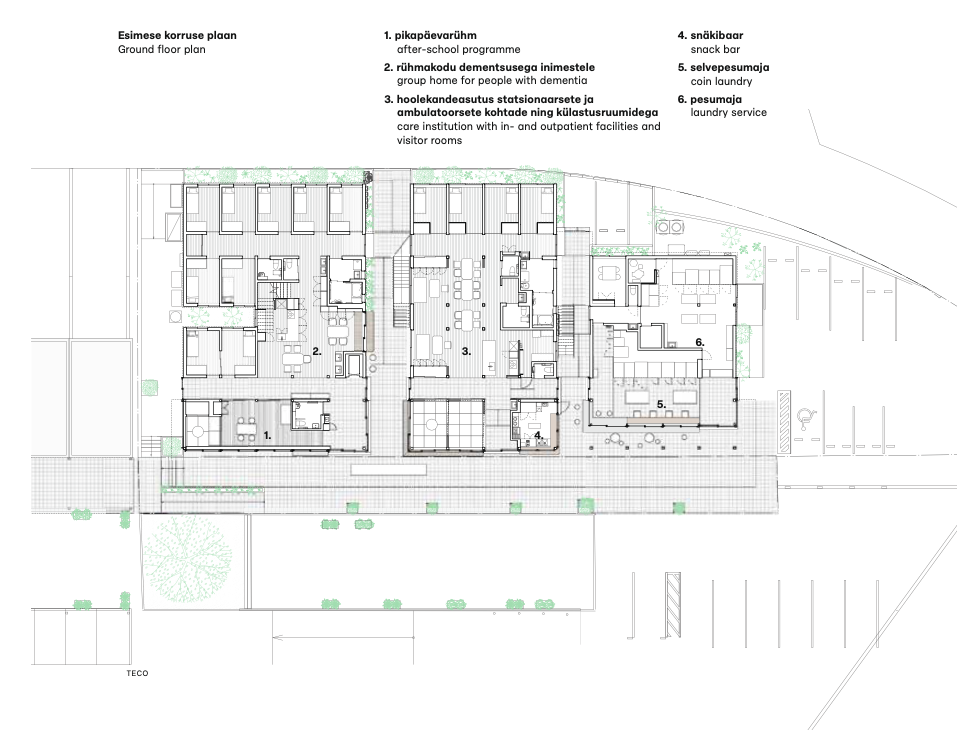

Kasugadai Center Centre is a new kind of community centre that integrates seven different functions, including a coin laundry, snack bar, care home, and classroom.

Photo: Makoto Yamamori

An exemplary project in this regard is the Kasugadai Center Center, a recently completed multifunctional care facility in Aikawa, a town on the southwestern periphery of the Tokyo metropolitan area. Aikawa is a post-industrial neighbourhood struggling with a lack of economic opportunities and outward migration, which is leaving vacant houses and an elderly population in its wake: a context not unlike many other stagnating communities across Japan where the vulnerabilities of a greying society appear most acute.

For decades, the supermarket Kasugadai Center had played an important role as the community’s informal heart, providing a meeting place where local residents could come together and exchange news. As a magnet for the larger region, it helped to attract users of all ages to the modest shopping street and civic complex (with facilities such as a public auditorium) in which pride of place was central.

The long eaves that extend over 2.7 meters into the street provide shelter for the threshold space that mediates between the street and the interior.

Photos: Yasuaki Morinaka

The new centre replaces a former supermarket in the same location, which was closed in 2016 and had been an important meeting place for the local community.

News of the supermarket’s closing in 2016 was the starting point for a long and complex process that resulted in this project. The architect, Chie Konno, had been involved in Aikawa since late 2015, when she was invited by a local welfare organisation to work on a separate commission with a small care facility that made use of one of the abandoned storefronts in the shopping street. Recognising the large hole that would be left in the community by the imminent disappearance of the supermarket, the architect began working with the client organisation to retool their original project into something much larger: a concept for a new ‘center’ to take the supermarket’s place, which would weave together care functions desperately needed in the neighbourhood with the informal role of a space of exchange that the original building had had. Since the establishment of a new welfare facility is subject to municipal planning and procurement regulations in Japan, the architect and welfare organisation needed to convince the local authorities of the necessity of combining multiple functions and approaching the problem in an innovative manner. Thus, in 2017, they established a nonprofit organisation, ‘Aikawa kurasu labo’ [‘Aikawa Living Lab’], in order to collect input from local residents and potential users, and formalise their requests. Over the course of five years, at the start of which it was not even clear that the project would go forward, the group organised a series of workshops to get to know the neighbourhood and its needs, feeding the gathered ideas into a vision for a complex that would go beyond the traditional boundaries of a care facility. After multiple consultations with the municipality, the group succeeded in having their idea of a hybrid, open complex integrated into the town’s planning framework, paving the way for the project’s realisation.

The common room is a multipurpose space open to everyone. Its cleaning is provided

by people taking part in an employment re-integration programme.

Photos: Yasuaki Morinaka

Height differences and movable partitions demarcate the boundaries between circulation and programme, semi-public and private, and allow for flexible levels of privacy.

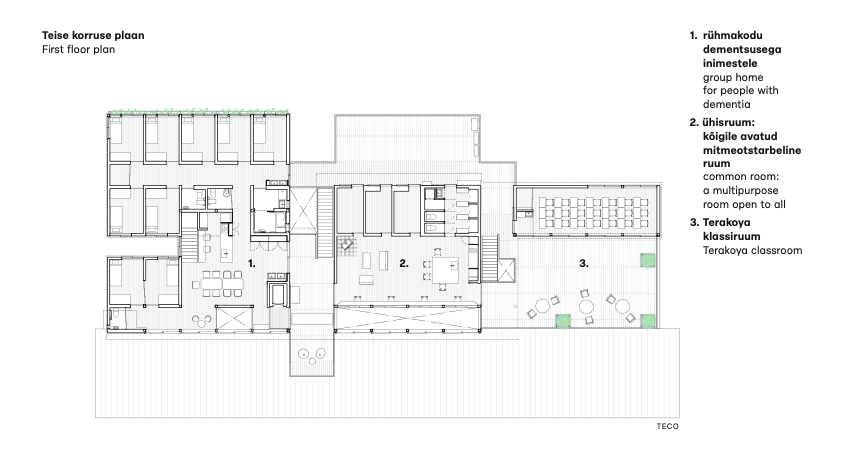

The result, which was finally opened in 2022 after nearly seven years of development, is a new form of community center that integrates no less than seven functions serving the neighbourhood’s social, gastronomic, and infrastructural needs: a group home for people with dementia, a nursing clinic with in- and outpatient facilities, an after-school programme for children with disabilities, a publicly accessible common room, a multifunctional classroom, a coin laundry, and a snack bar. The common room, classroom, coin laundry, and snack bar are operated by a welfare organisation providing workplace integration for people with disabilities, thus fulfilling a further care function.

The long eaves of the main façade allude to one of the main features of the old supermarket structure and provide shelter for the threshold space beneath them that mediates between the street and the interior. Extending over 2.7 meters into the adjoining street, the so-called ‘promenade loggia’ with its external benches has proven a popular place for gathering even outside of the center’s business hours.

The building itself is threaded with corridors that seamlessly transition from the street and form semi-public alleyways linking the various functions together. As in a traditional Japanese home, height differences and movable partitions demarcate the boundary between circulation and programme, semi-public and private, and allow for flexible levels of privacy. Through the functional mix of facilities addressing users of different ages, the complex gently supports interactions across generations.

A city-within-the-city that balances programmatic complexity with a disarming openness, Kasugadai Center Center shows how architecture can be deployed in repairing an urban fabric left disjointed by economic and demographic upheaval: a building as a form of care.

S AM Swiss Architecture Museum, Yuma Shinohara, and Andreas Ruby (eds.), Make Do With Now: New Directions in Japanese Architecture (Christoph Merian Verlag, 2022). In 2022, Yuma Shinohara curated the exhibition Make Do With Now: New Directions in Japanese Architecture at the S AM, which was also shown at the Estonian Museum of Architecture in 2024. He edited the eponymous catalogue, from which this text is adapted and expanded.

Photo: 75W Studio

YUMA SHINOHARA is a curator at the S AM Swiss Architecture Museum in Basel, Switzerland.

HEADER photo by Yasuaki Morinaka

PUBLISHED: MAJA 2-2024 (116) with main topic OLD AGE

1 As of 2020, approximately half of them (fourteen percent of the total population)

are aged between 65 and 75, and the other half (fifteen percent of the total population) are over 75. See: Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan, ‘Waga kuni no jinkou ni tsuite’ [‘On the Population of Our Country’], accessed 9 May 2024, https://www.mhlw. go.jp/stf/newpage_21481.html