OUTSET

Concrete paradox

Kadri-Ann Kertsmik, ill. Cristin Marii Titma

PROJECT

Kiemas

Šiauliai, LT

After Party

Matas Šiupšinskas

ESSAY

Tidings from a Man-Made Plateau

Roland Reemaa

CASE STUDY

Ankru 8

Tallinn, EE

Molumba

CASE STUDY

Thoravej 29

Copenhagen, DK

Pihlmann Architects

IN PRACTICE

Baukreisel: Concrete Matters. And how to make it matter more

Christian Roth

INTERVIEW

How To Bolster a Concrete Panel?

Laura Linsi, Keiti Lige, Elina Liiva, Helena Männa

SCRIPT

A Script of the Tragicomedy of an Apartment Building. Two scenes

Märten Rattasepp, Elina Liiva

PROJECTS

Three Houses. Three Questions

Madli Kaljuste

>> Industrial Villa in Naujoji Vilnia

Vilnius, LT

Case Studio for Architecture

>> House on Purje Street

Tallinn, EE

ÖÖ-ÖÖ

>> House 61

Jūrmala, LV

Sampling

ESSAY

Concrete and Paranoia

Ingrid Ruudi

CONCRETE

Concrete is the cornerstone of the Anthropocene. By building dams, bridges, tunnels, roads, and airstrips, humans have taken over and taken advantage of entire landscapes. Concrete floors, walls, and interiors have been essential for creating sanitary environments, thus having a direct effect on improving human health and increasing life expectancy. Concrete embodies the modernist ideology of development, which remains a part of nearly every architectural project today.

Architects and engineers have been drawn to concrete for its structural as well as aesthetic qualities, and yet, most of its use boils down to simple efficiency and relatively low cost. The raw materials for concrete are sourced globally, its production is scalable, and its casting and usage are universally replicable. This has shaped our modern construction (mono)culture, as well as the scope of spaces we can create.

Durability is a quality often emphasised in concrete and one that serves as a justification for specifying it. As a material, concrete can last hundreds of years, survive earthquakes and nuclear attacks. And yet, the lifespan of our contemporary concrete buildings is often merely 50 years. Christian Roth notes that short life cycles of buildings are even favoured to ensure continuous new investments and economic growth while ignoring the environmental, social, and cultural consequences of demolition and construction.

Estonian Prime Minister Kristen Michal has said while discussing the new Tallinn Hospital that the act of pouring concrete cannot be the catharsis of human life, which the questions ‘why’ and ‘for whom’ tend to follow rather than precede. Where is the line between genuine development and pointless construction? How to use concrete reasonably rather than wastefully? In what form should concrete figure in contemporary architecture?

Editor-in-chief Laura Linsi, Editor Madli Kaljuste

August, 2025

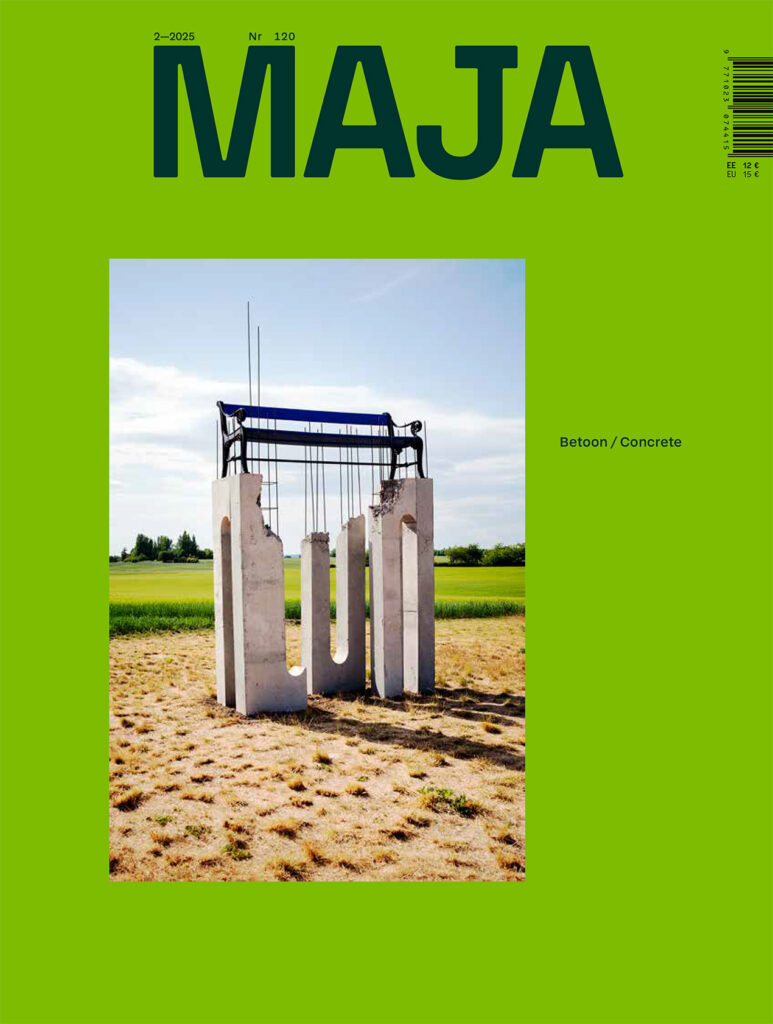

ON THE COVER: Evita Vasiļjeva, outdoor sculpture, If There Is Something Heavy, There Should Be Something Light I, Møen, 2023. Photo: Thomas Gunnar Bagge

DESIGN: Unt / Tammik