MUSTJALA CARE HOME AND DAY CENTRE

Architecture, interior architecture: molumba

Location: Mustjala küla, Saaremaa, Eesti

Client: Saaremaa vallavalitsus

Planting concept: Maarja Gustavson

Structural engineer: Margus Allik

Contractor: Kuressaare Ehitus

Built: 2022

Project size: 674m2

Some years ago I came across a story about how the city of Tallinn wanted to build a social housing unit for the elderly. The Estonian Association of Architects supposedly met some city officials and suggested to hold a public architectural competition for the building. The official’s answer, however, was rather shocking for the architects—why have a competition for such an insignificant building, if all that is needed is a series of residential units connected by a corridor? Procurement is more than enough!

In case of schools, municipal government houses and other public buildings, architecture competitions have become a regular phenomenon. Competitions are organised to find new ideas for and alternative approaches to the building. And yet, in the case just described a space that is likely to be the last abode for many of its residents was not deemed worthy of this sort of deeper interpretation. The society extolls beauty and youth, whereas aging—well, best if it takes place somewhere out of sight. If most of your life is already past you, what more do you need than a spot in some corridor where you can lie down and quietly wait for your demise?

One interesting reason for why societies are moving away from dealing with the topics of old age and death is put forth by French historian Philippe Ariès. According to him, the 20th century saw the rise of the belief that life is supposed to be happy—or at least seem so. Old age and passing away are not perceived as something natural and happy, and thus, those aspects of life are simply ignored.1 A good spatial illustration of this approach to life is The Villages in Florida, which is advertised as the best and most popular retiree community in the United States.2 The idea was born in the 1960s, when Michigan businessman Harold Schwartz bought some cheap land in Florida and established something that has been called Disneyland for Seniors. Lance Oppenheim has portrayed it in his film Some Kind of Heaven, which follows four residents of The Villages. The film gives the impression that the elderly who have gathered there are trying very hard to forget their age. In the evenings, they go to discos and parties, play golf and take drugs. The outdoor space around the residences is depressingly bleak—nature has been destroyed and the air is full of pesticides meant to keep the golf lawn impeccable. Everything there seems to shout that the important thing is to be pretty, cheerful, sexy and hard-partying!

Mustjala Care Home and Day Centre is something radically different from the above. It is a wholesome environment where ageing and all that goes with it is duly accepted. It is a novel type of establishment in Estonia that combines the functions of care home and day centre, thus addressing the lack of both nursing home places and social housing in one go. Furthermore, the locals felt they needed a place for socialising, which is what gave the municipality the idea of combining the functions. The spatial idea for the building was born through a public architecture competition that turned out to be very popular—there were altogether 36 entries. I believe that one reason for such a large number of participants was namely the type of the building.

Mustjala is a small village in Saaremaa, 10 km2 in size, with a population of 253. Taking a stroll there in early spring I feel a bit like an intruder—it is as if some pair of eyes is constantly watching my movements, and the few locals who happen to pass by will then stop and stare for a long while, wondering about the stranger who is nosing around as cocks crow in the background. The care home is located on the edge of the centre of Mustjala. The main traffic route goes right past it, and thus, it is impossible not to notice the building when driving through the locality. The building fits well with local spatial stratifications that include a 17th-century manor building, 19th-century church, 20th-century gorgeous wooden houses, a Soviet-era collective farm building and a relatively new Coop supermarket.

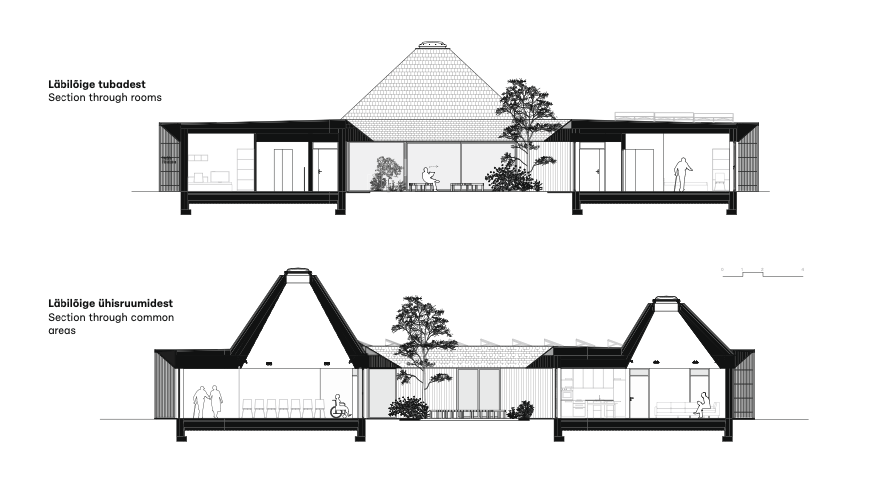

On the plot adjacent to the care home, there is a prefab apartment building with a lone woman bustling about in its yard to loud music. Life goes on and springtime chores need to be taken care of, but this does not bother the care home residents, whose rooms are facing the other direction, towards a large courtyard with apple trees that should be bearing fruit in a few years’ time, and for which further vegetable beds are planned. The environment is calm and quiet. The residents go to the road that passes through the village to conduct their observations. The supermarket is a few hundred metres away; most of the seniors do their shopping there by themselves. The care home building itself is relatively small, about 600 m2 in size, and reminiscent of a large private residence rather than any old folks’ home that I have seen. All around the building, the eaves offer shade under which one can rest and observe the village, thus enabling to spend time outside in any weather.

The entrance to the day centre is separate from the entrance to the care home and located on the village side of the building. The centre features a hall with a piano, laundry room, kitchen, and sauna. By the piano in the hall I met my first resident of the care home who said that playing is good for keeping the fingers warm. And just like that, ‘Flohwalzer’ resounded through the building. These rooms can be rented out to people living in the municipality; this is where local hobby groups gather and workshops are organised. Also, every week the local social worker brings people from nearby localities to the sauna. The islanders who lack proper washing facilities at home can enjoy throwing steam, warm water and interaction. Philosopher Vivian Bohl has said that social relationships are the locus of life’s deeper meaning; people have a fundamental need of belonging to a community and being loved.3 Studies have shown that well-functioning social relationships can lead to better heath and increase subjective well-being. We should not forget this when tackling to ageing-related challenges.

In this regard, a closer examination of the society in Sweden, for example, reveals that despite having long been held up as a good example of how to solve problems of different age groups, they have overlooked something important. Italian-Swedish filmmaker Erik Gandini’s 2016 documentary The Swedish Theory of Love looks into the issues with Sweden’s ageing population. The film reveals that the main concern among the elderly in Sweden is namely loneliness, a lack of social relationships that is connected to living in a city apartment, a fast pace of life and desire to be independent. Family relations, friends, interactions and traditions have been lost, and all in all, social security and comfortable living spaces notwithstanding, the elderly are quite unhappy. I witnessed a similar kind of sad loneliness in the hospice of Tallinn Diaconal Hospital, where I volunteered while writing my master’s thesis in architecture. There were few visitors, the nurses were always busy, the patients stayed mostly in their rooms and did not interact, and even the windows did not offer much of a view. People quickly became dejected and lost their will to live.

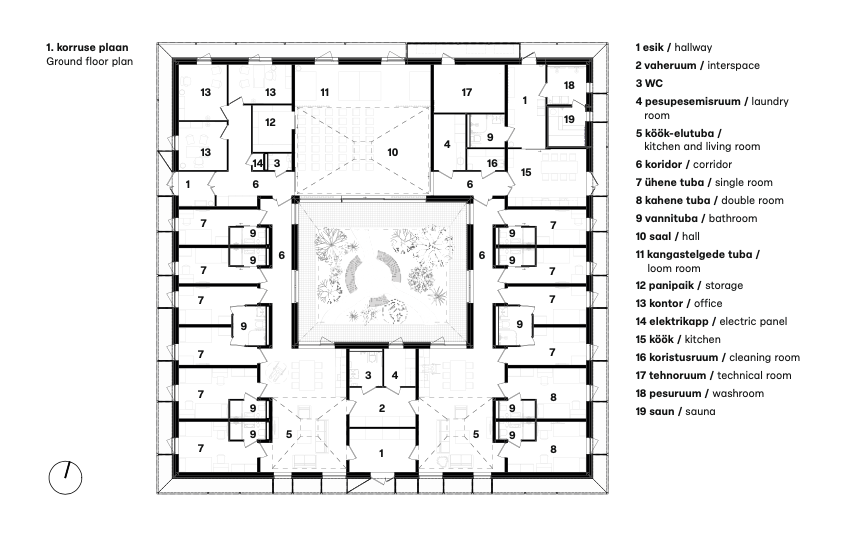

The two residential wings are on either side of the courtyard. The spaces are designed so that the residents can move comfortably with the support of wheelchairs and other aids.

On the contrary, in Mustjala, the space contributes to social relationships and interactions. Entering the care home, the first room is the hallway where you leave your footwear. From there on, you can choose to go left or right—on each side, there are spaces with an identical floor plan, consisting of a common room with kitchen and eight private rooms for the residents. My first impression—it is as if stepping into someone’s living room. The furniture is eclectic, somewhat weathered, there are newspapers on the table, board games on the shelf, a large TV set in one corner. The kitchen is simple and features a large dining table.

The first resident who moved into the building, a woman who is now 93 years old, says that it was difficult at first. She was brought in from Leisi village, a farmhouse buried in snow, into this brand new building where there were no others at first. For someone coming from one’s own farm, everything felt very different and even slightly eerie. But soon, other residents started moving in and the old lady quickly got used to it. Emotions—they go up and down, just like they have been going throughout the whole life, but now she has friends and helpers here, and also a space of one’s own to withdraw to when she needs it, of course. Into these small rooms, the residents can bring their most important things that make them feel at home.

All around the building, the eaves offer shade under which one can rest and observe the village, thus enabling to spend time outside in any weather.

The hostess of the care home is present from Monday to Friday; there is no separate caretaker or nurse. The residents have to manage by themselves. They support each other when in need, and in critical situations, they can call an ambulance. Manager Ave Väli says that a care home of this size is perfect—there aren’t too many people and all the residents get along with each other. She tells me that the residents in one side of the building have by now become like a large family—the men are often baking cakes and cooking porridge for the women, and everyone is taking care of each other, chatting, discussing world affairs. During my visit, three residents were sitting on the couch, one in the armchair, and they were just being silent. Even the TV was switched off. Over their head stood a churchtower-like structure, emanating light. ‘Life is peachy!’, said one of the women upon being asked how they are doing there.

Mustjala care home has succeeded in combining grandeur with simplicity. The building leaves a very honest impression, nothing is missing or superfluous. The block walls have been painted white, with the colour of the blocks still shining through; the floors are covered with simple grey linoleum. A respectable appearance is achieved with a ceiling that reaches toward the sky. One of the building’s authors Johan Tali says that the only so-called design element consists in the large sliding doors of the hall, which were painted with stripes reminiscent of Mustjala’s folk costume pattern.

While working on my master’s thesis, I happened to read about an orphanage called Ospedale degli Innocenti, opened in 1445 in Florence, Italy, and designed by architect Filippo Brunelleschi. I was fascinated by the idea of this building—children could be brought there by a special door that enabled one to remain unseen. There were cases of parents giving up their children due to tough circumstances, but then volunteering to work at the orphanage to feed them. The building was built in a modular way. At first it seems very strict and symmetric, but in fact hides an exciting system of inner courtyards and passages. Mustjala has a similar charm—the simple shell hides a garden where it is possible to organise concerts, simply relax, or even just admire it through the windows. The secret garden does not make itself known from outside. It is in centre of a circular movement path that passes through the building. I have noticed it with children that when a building allows for circular movement, they immediately seize the opportunity. Endless movement without ever turning back is inviting. Doing these endless circles is possible in Mustjala too—by moving from the living room to day centre rooms, from there on to the living room of the other side, then hallway and then back to the beginning again. In addition, every resident has the opportunity to step directly outside from their room. Residents can take care of their business almost invisibly; no one needs to feel like they are imprisoned.

Mustjala care home and day centre was meant to be a pilot project for a standard design in Saaremaa. There is a shortage of care home places and the same kind of building was planned right away for Leisi too. While initially it was feared that life in such a care home would be too expensive, today we see that monthly bills for the residents do not exceed 300 euros. The residents pay for the food, which on weekdays is brought from Mustjala kindergarten and basic school; in the evenings and on weekends, the residents can manage by themselves. The upkeep of the building naturally relies on support from the municipality. Unfortunately, building other similar care homes is currently on hold due to financial difficulties. The building cost 1.8 million euros—perhaps a private investor could chip in?

Take for example the Maggie centres for cancer patients, which have been built with donations and grants. The centres were created by Maggie Keswick Jencks, who died of breast cancer in 1995, and her husband Charles Jencks. Cancer patients can go to Maggie centres with their loved ones, receive support services, aid, and information about the disease. Much emphasis has been put on architecture, the buildings are designed by world-famous architects and several of them have also resulted from architecture competitions. Their design is strongly intertwined with psychology—Maggie centres do not have that classic hospital atmosphere, no reception desk and no uniformed specialists.

I asked Johan Tali whether he feels that he should become an advocate of such projects. Johan answers that he would like think that he is an advocate of good architecture rather than any particular social group. That is understandable. And yet, I am left uneasy by the fact that Estonia has only one such space that truly values older people. An old folks’ dorm, like Johan himself describes it.

I went to school in Tallinn French Lyceum whose slogan was ‘Probi estote per totam vitam!’ (Latin for ‘Have dignity throughout your life!’). Returning from Mustjala I found myself thinking that perhaps the happiness and contentment of our lives rests namely in dignity—dignified behaviour, living, interacting, thinking, as well as dignified space. So let us do everything we can to ensure that everyone could have a space where they can have dignity throughout their lives.

INKE-BRETT EEK is an architect who in her spare time ponders over social and environmental issues.

PHOTOS by Johan Tali.

HEADER: The building fits well with local spatial stratifications that include a 17th-century manor building, 19th-century church, 20th-century wooden houses, and Soviet-era collective farm and pre-fabricated apartment buildings.

PUBLISHED: MAJA 2-2024 (116) with main topic OLD AGE

1 Philippe Ariès, Western Attitudes toward DEATH: From the Middle Ages to the Present, tõlkinud Patricia M. Ranum (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press 1975), pp. 86–87

2 Website of The Villages of Citrus Hills

3 Vivian Bohl, ´Inimene kui sotsiaalne loom´, Sirp, 14 August 2015