‘… when humanists accuse people of “treating humans like objects”, they are thoroughly unaware that they are treating objects unfairly.’ Bruno Latour

My old man has no name—he has an address. People passing by often stop in front of his shabby and weathered façade, look up in awe, take a moment to reflect. At first it was startling to see strangers staring motionlessly at my kitchen window, but then I understood their actual point of interest. The old man wears a sign with the year 1914, a construction date that is not quite confirmed by the National Register of Cultural Monuments, but it is nice to think that the gentleman is celebrating his 110th birthday this year. Back when the red barracks that my old man is a part of were built, they played an important role in the twofold function of the Karjamaa-Miinisadama area where various military facilities and factories were concentrated around the harbour and the ‘Arsenal’ centre. The first residents of the barracks were Germans, but very soon—already in 1920—they were replaced by senior personnel of the Estonian Defence League. As I try to imagine these previous residents, I am struck by how brief and tenuous my own occupancy of these rooms is. My old man has had a taste of the Tsarist period, and witnessed both the First and the Second World War. The world is changing, he is still standing. When the old man was still a young boy, there was a pasture here, now commemorated by the cow statue in the park of Karjamaa subdistrict. My great-grandmother, a Tallinn native of several generations, is said to have brought her family’s only cow to graze here every morning. The cost for one cow was 5 kroons. It is possible that my old man was already hanging around here at the time—newly built, but already present. The old man and my foremother might even have been acquaintances.

Old age and surprises

‘The old man has not always been an old man in my eyes. At first, there was just an apartment in an ancient building. Mainly because the cobbler always goes barefoot and I could not afford anything newer. Naturally, I was also fascinated by the history of the building. As time went on, however, I discovered that every new day in an old building is full of surprises. It is as if by being a resident in an old house, I am also carer for an old gentleman who needs help with everything. One day, the roof starts leaking; then, the chimney starts smoking up my rooms; and just as I think that I have managed to solve every emergency, all the plaster from the balcony ceiling falls off in one piece. Circling in this cycle of order and disorder I realised that the same rules that apply to the elderly and young children also apply to old buildings. You have to relinquish your expectations and go with the flow. From that day onwards, we have been working together as a team. I listen to his needs, his aches of the day, and try to comfort him as respectfully as I can. This is not surrender, but respectful adaptation. My old man, just like other old buildings, is full of surprises, and thereby risky and costly, but—as I would like to emphasise—nevertheless loveable.

Old age and renovation

It is sadly funny that in discussing the renovation of residential spaces, one first has to discuss funding methods rather than the spaces themselves. The simplest and most widespread ‘business plan’ consists in expanding the building in a way that allows for added economical value in the form of new apartments, which can then be sold off to finance the rest of the renovation. For instance, it is common to turn the attic into an additional floor. Small-scale renovation works can be carried out without such a plan, of course—this is what apartment associations’ repair funds are for. It is also possible to take a loan, but this will often be insufficient for a complete renovation. The apartment buildings under heritage protection face a further quandary. On the one hand, they are more expensive to renovate than ‘regular’ apartment buildings, for the work is more detailed, complex, unpredictable, and can be carried out by qualified specialists only. Shortly, the risks are greater. On the other hand, historical apartment buildings often do not allow for any ‘business plans’ because adding floors or extending the building in any other way is prohibited. Thus, quite a few old men might find themselves trapped. It is difficult to secure additional funds and homeowners are unable to undertake costly renovations. But the decline of historical apartment buildings means losing certain historical strata in the urban space around us. And with their disappearance, we risk losing one of the means for perceiving time.

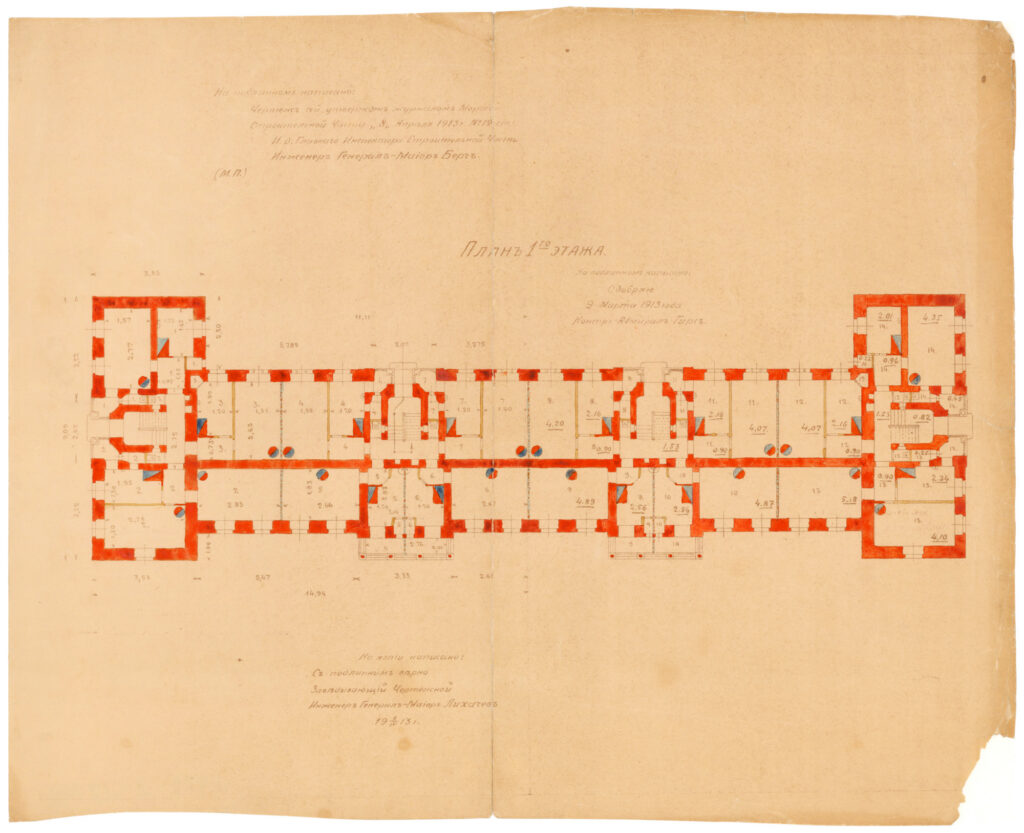

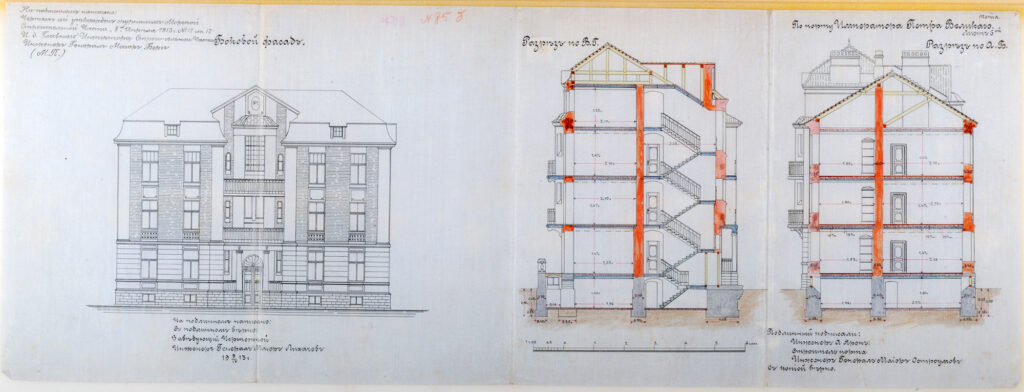

Photo: Eesti Meremuusem SA

My old man has already lived through one spruce-up in 1964. This fresher look is marked with another year number on the façade. But this was already quite some time ago, and today, the gentleman badly needs another renovation. Here it is worth recalling that in the current design practice, a building is designed with a fifty-year-perspective—thus, my old man, like an old cat, has already gone through several lifetimes. This has saved the need for building (and perhaps demolishing) several new buildings. What an economical use of resources! Then again, no one was able to profit from building new buildings in my old man’s place. Hence the question—are old buildings worthless in a capitalistic society, given that they are unable to manage self-sufficiently?

Sure, there are renovation grants that can be applied for once a year. Renovations of buildings under heritage protection are funded up to 70%. Yet, my attempt to apply last year was unsuccessful. I applied for a grant to replace two windows and a balcony door, but despite having some idea of the construction field, I was bogged down in paperwork, and the limited timeframe for correcting deficiencies ultimately proved fatal for my application. This made me understand why my old man’s façade looks like patchwork—people are often unaware of the grants, the application process is complicated, the requirements are tough, and windows that do not meet heritage protection requirements are cheaper anyway, grant or no grant.

Let us assume here that residents of older buildings do not live in newer ones simply because they cannot afford it. They might be—and often are—people of advanced age or some other vulnerable social group. Thus, it is understandable that they have trouble paying for a more expensive sort of renovation. The high cost of renovating old buildings has today joined hands with the tight economic conditions of senior residents. So, would it be most reasonable to simply abandon the old man? And go where? The main issue, then, concerns preserving our spatiotemporally diverse environment while keeping it accessible for as diverse social groups as possible. Are we doing enough today to support the survival of heritage-protected buildings that are economically disadvantaged due to restrictions and special requirements?

It is important to acknowledge that on the eve of a new renovation wave, we face the challenge of how to prepare an ageing society for ageing buildings. In my view, the first step towards a solution is simplifying the renovation process. It is necessary to lay down clear guidelines for the renovation process that would make it intelligible also to (older) residents for whom the construction sector, building regulations and funding applications are an unfamiliar territory. In this case we could hope that the combination of clarity and grants will indeed help us preserve our historically diverse environment.

In conclusion

‘It is evening and a row of lights passes by my kitchen window like dwarves. The lantern tour of historical Kopli stops in front of my old man. As always, they take a moment to discuss the history of the red barracks: ‘This ensemble consisting of three buildings was built in 1915 following a design by Aleksandr Jaron. There were supposed to be ten buildings’. I imagine my old man quietly chuckling and rejoicing over these young visitors. People on these tours as well as those staring into my kitchen window recognise that the old man has obvious value—a value that every simple city dweller can perceive and wordlessly acknowledge in the form of these little stops.

MAE KÖÖMNEMÄGI is an architect, who in her spare time is renovating her 100-years-old home in Karjamaa neighbourhood.

HEADER photo by Siim Vahur

PUBLISHED: MAJA 2-2024 (116) with main topic OLD AGE