Infrastructure—but is it only that?

The current transportation land in Estonian cities needs to be reimagined. Mobility is gradually being diversified with new roads for public transport, bicycles, and pedestrians, but our approach to transportation land should not be limited to that. Many roads in Estonian cities are too wide, which is a remnant of modernist planning—the distance between buildings can be up to 100 metres. In comparison, the width of a city block in Manhattan is 80 metres. Space-wasting jumbles of roads are particularly common in Soviet-era residential districts, but even on Liivalaia Street at the very centre of Tallinn, the space between buildings sometimes stretches up to 60 metres.

The land area of Estonian cities is large, but the floor area ratio is low. This creates long daily commutes to work and school. Our habit of viewing properties as generally monofunctional results in distant shopping centres and homogenous street space, thus promoting the use of personal cars. Housing developments are further and further away from the centre, thus accelerating urban sprawl. However, developing the suburbs does not densify the city, but only expands it.

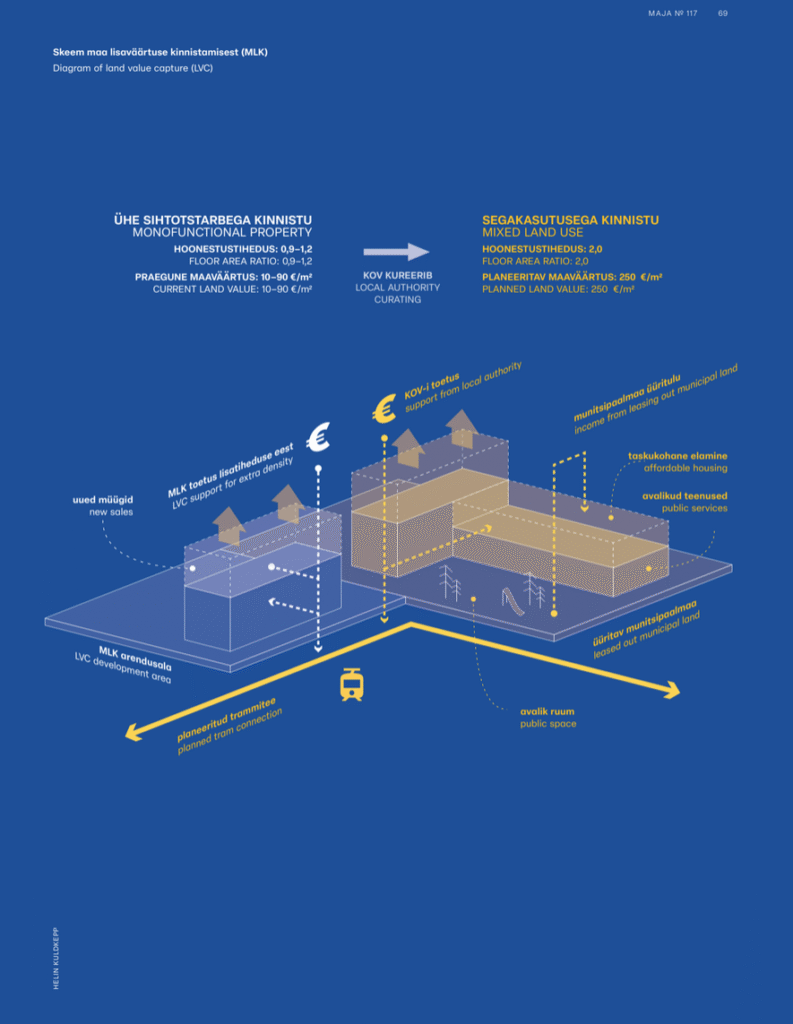

In order to create human-scale urban space, we need to leave behind the entrenched view of transportation land. We need to let go of the initially defined land use. Besides diversifying and integrating the means of mobility, it is important to focus on densifying the street space and areas around public transport routes—in other words, on transit-oriented development (TOD).1 Ideally, this would also involve land value capture (LVC), redirecting the value created by public investments into social projects, which I will now introduce in more detail.2

Creating the city’s initiative for building up municipal land

Infrastructure is for the most part public property, most of which belongs to municipalities. Spatial planning and development in Estonia are often based on private property and thus, a complete view is lacking in planning. New developments are erected on sites that have been bought up by private owners (e.g., Lahekalda), but were often public property before. When the state or local authority sells its property, it gets a one-off financial benefit, but loses in the share of owned land. In Finland and the Netherlands, however, public land is handled differently—it is leased. Granted, Amsterdam owns 85% of its land3 and Helsinki owns 64%,4 whereas Tallinn owns only 36%,5 but the small share of municipal land in Estonian cities is not an obstacle to developing that municipal land. Long-term land leasing enables to retain public ownership and develop the land under contract. Thus, the local authority has more options in laying down the contract terms, whether it be the share of affordable housing in the development or building public functions such as kindergartens, schools, libraries, parks or public infrastructure. However, the whole process requires a robust, transparent, and collaborative mechanism that would actively involve the private sector.

The development of public land, including municipal land, is an urgently needed and currently barely existent element in Estonian spatial planning. Market-based planning that focuses mainly on the more affluent part of the population is not sustainable, neither socially nor environmentally. Tiit Tammaru has remarked that building new buildings in only a few compact subdistricts leads to the so-called vacuum cleaner effect, drawing away the more affluent population from other parts of the city and thus generating spatial segregation.6 The real estate market should also feature other types of ownership as a counterweight to private development, including publicly funded more affordable dwellings. Pärtel-Peeter Pere emphasises that the local authority could demand rental apartments to be built on municipal land, as it has been done in other European countries.7

Local authorities as owners of municipal land and administrators of the building process must manage planning in a holistic way. Or, in the words of Jüri Raidla: ‘Property is not only a right, but also an obligation’.8 Thinking of municipal land as mere mono-functional infrastructure stifles the creation of human-scale space. By narrowing and reimagining roadways and intersections, we can densify the city and create human-scale environments. At times, this might mean a whole new row of buildings.

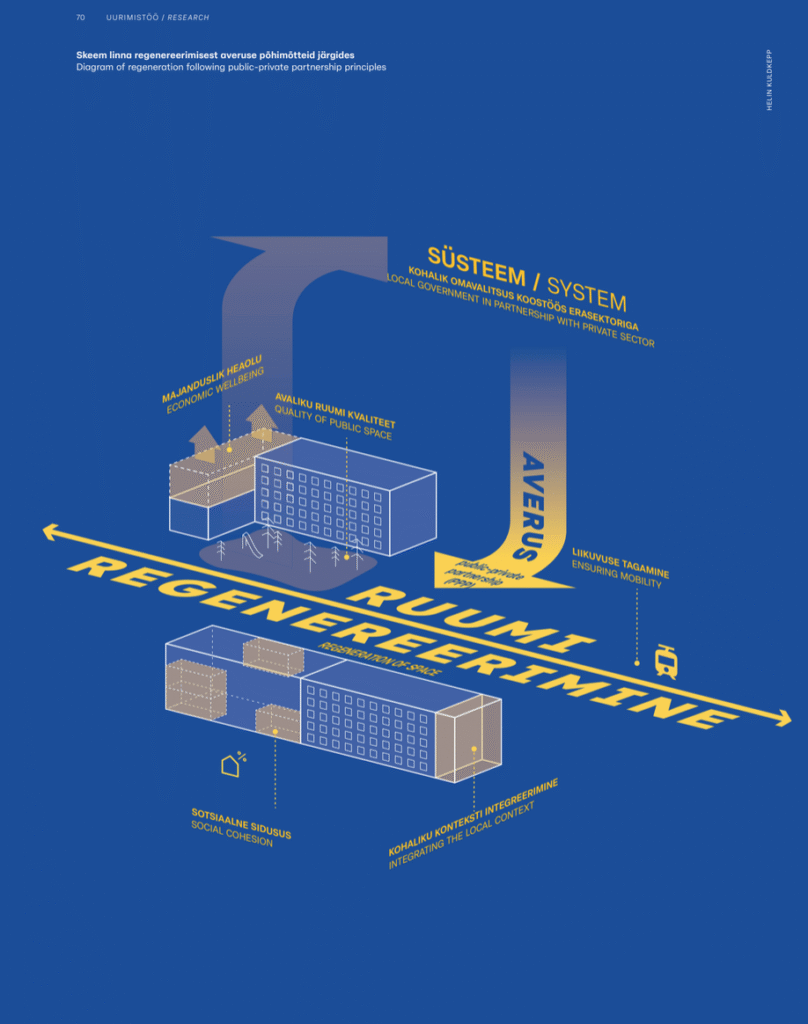

Using public-private partnership (PPP) with land value capture (LVC)

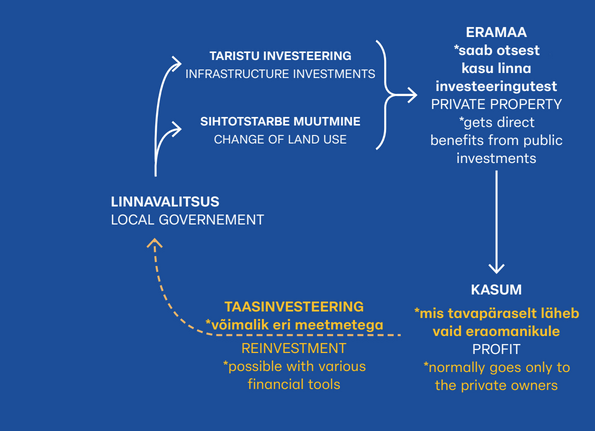

An integral part of comprehensive spatial planning is public-private partnership (PPP). In theory, PPP ensures the creation, administration, and financing of high-quality space. An efficient practice, however, requires a transparent mechanism that would guarantee benefits for both partners. One common mechanism for employing PPP is land value capture (LVC), which is based on changes in land value. LVC takes into account the increase in land value that comes from public sector investment and redirects it through taxes on private sector profits into social priorities, offering the private sector in return, say, additional density or development opportunities (by leasing out the land). One of the most transparent methods is to use the profits (e.g., 5% of them) from new developments to fund the building of infrastructure or affordable housing. The infrastructure tax imposed on new developments can be changed based on floor area ratio. A more stable option for financing affordable dwellings, however, might be the income from leasing out municipal land. Here, the first step must be taken namely by the local authority, the main curator of urban space.

Public sector investment into high-quality space and mobility creates added value that must be reflected both in land value and the funding scheme for planning. The greatest added value comes from building transportation infrastructure, land use change, leasing out the land (creating development opportunities), and increasing the floor area ratio.9 In the context of Estonia as well as European models more broadly, these depend mostly on local authorities. Thus, the local authority as the main curator of space and planning manager must ensure that land value capture would be as transparent and clear as possible in order to maintain credibility.10 All qualitative changes affect the value of surrounding properties. Usually, the value of intracity transportation land is 10 €/m2 (40 €/m2 in city centres), whereas the value of land designated for mixed use buildings is at least 150–350 €/m2, depending on the location.11 Land use change by itself already has an enormous effect, not to mention the other options. LVC creates the necessary financing framework for planning to ensure affordable housing, public transportation, and public space. The main aim must be benefitting the society as a whole.12

The most common LVC method is transit-oriented development, in which a development tax is imposed on the surrounding private developments to fund the construction of planned public infrastructure. Tokyo and Hong Kong, for instance, use land value capture to fund the building of metro lines. In the case of Tokyo, this also means land consolidation, increasing floor area ratio, and introducing mixed land use.13 Hong Kong benefits from the fact that the land there is fully publicly owned, which enables not only to subsidise certain types of land use, but also to prevent private sector speculation by seizing the value of undeveloped land.14 On the other hand, LVC is not limited to funding infrastructure projects, but can also be used to demand affordable dwellings from developers, as it is done in England.15

Estonian public sector investments often bring direct benefits only to the private sector, which uses the improved environment to increase prices and make a profit. For instance, 46 (52.616) million euros from Tallinn and European funds spent on the tram line to Old Harbour generate indirect profits mainly for the private sector.17 Using LVC would enable the city to demand contributions to infrastructure or affordable apartments through its investments. This is an important consideration in planning future tram lines.

The most interesting spatial opportunity with land value capture is (public) transit-oriented development, which prioritises densifying the city at the expense of transit corridor land—especially near the stops.

(Public) transit-oriented development as a future infrastructure opportunity

The most interesting spatial opportunity with land value capture is (public) transit-oriented development, which prioritises densifying the city at the expense of transit corridor land—especially near the stops. Regardless of the type of public transport infrastructure being built (tram line, metro line, railway), it is necessary to densify namely the areas adjacent to the transit corridor so that the new tram, metro or train would be justified. Transit-oriented densification takes a critical look at the current wasteful situation with transportation land, comprising both land use issues and land value capture. In the context of Tallinn, one could focus on developing the areas around planned tram lines, such as the prospective Liivalaia and Pelguranna lines. Spatially, the most efficacious solution in cities is to rethink intersections. For instance, it would be beneficial to densify the intersections of Endla Street in Tallinn and the intersections of Pikk Street in Pärnu. On the national scale, Estonia should work on rethinking and developing the train stops of both Elron and Rail Baltic in order to realise their potential. Yet, the current status of public land as ‘infrastructure’ stifles the development of human-scale space.

By densifying transit corridors, local authorities can designate LVC development areas around transit lines (e.g., consolidated municipal land, empty private properties) and prioritise their development. In order for LVC to function efficiently, there needs to be a trustworthy transport system, which most citizens can rely on in their daily lives, and transparent and high-level transit-oriented development.18 Taxing adjacent private developments enables to finance infrastructure projects while offering in return additional density and mixed use. Alternatively, local authorities can introduce an affordable housing requirement for LVC development areas, offering the developers additional density. The income from leased municipal land can also be used to fund affordable housing. In this way, Tallinn could densify the planned tram line on Liivalaia Street (e.g., Liivalaia-Juhkentali and Liivalaia-Tatari intersections, parking lots), the Pelguranna line, and, in retrospect, the Old Harbour area (e.g., Narva-Hobujaama intersection, the area around Linnahall). Just by simplifying the jumbled road intersection of Mere, Ahtri, Sadama, and Põhja Blvd., it would be possible to free up significant amount of municipal land.

Developing the public transportation infrastructure is one of the largest value creators and the whole process can be steered by the local authority with the land that it owns. Naturally, this would also mean involving the adjacent private developments, but the starting point is clear—local authority as a creator of public and common good must take the lead. Building up the land under oversized roadways and intersections presents municipalities with a significant opportunity for transit-oriented development, all the while remaining fully confined to municipal land. Efficient (public) transit-oriented development might be the key for Estonian cities to restoring the spatial balance between transportation infrastructure, housing (availability), and people’s various interests and needs.

The article is based on Helin Kuldkepp’s MA thesis ‘Municipal Strategy in Urban Regeneration: Emphasizing Municipal Land and Land Value Capture in Spatial Planning—A Case Study of Lasnamäe’ that was defended in 2024 in the Estonian Academy of Arts.

HELIN KULDKEPP is an architect who specialises in planning. Helin’s professional interest lies in the systems surrounding physical space, including how legislation is expressed in the built environment.

HEADER: design by Unt/Tammik

PUBLISHED: MAJA 3-2024 (117) with main topic INFRASTRUCTURE

1 Hank Dittmar and Gloria Ohland, ‘An Introduction to Transit-Oriented Development’, The New Transit Town: Best Practices In Transit-Oriented Development (Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2012), pp. 1–18.

2 OECD, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Building a Global Compendium on Land Value Capture.

3 Natalie Bonnewit, Affordable Housing In Amsterdam and Copenhagen: Lessons for the San Francisco Bay Area, Urban and Regional Policy, no. 32 (The German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2017), p. 4.

4 Ari Jaakola, Teemu Vass, Solja Saarto, and Lotta Haglund (eds.), Helsinki Facts and Figures 2021, p. 4.

5 Geoportal of the Estonian Land Board, ‘Cadastral Data’.

6 Airika Harrik, ‘Inimgeograaf: ebavõrdsus on Tallinnas võrreldes muu maailmaga leebe’ [‘Human geographer: compared to the rest of the world, inequality in Tallinn is mild’], ERR, 10 February 2024.

7 Pärtel-Peeter Pere, ‘Linnaehituslik visioon põhjamaisest Tallinnast’ [‘Urban Development Vision of a Nordic Tallinn’], Sirp, 2 February 2024.

8 Jüri Raidla, ‘Maakasutajast maaomanikuks: võlud ja valud’ [‘From Land User to Land Owner: Pros and Cons’], Maareform 30. Artiklid ja meenutused (Trükisilm, 2021), pp. 93–109.

9 Eliška Vejchodská et al., ‘Bridging Land Value Capture with Land Rent Narratives’, Land Use Policy 114 (2022): p. 5.

10 Martin Alessandro et al., ‘Transparency and Trust in Government. Evidence from a Survey Experiment’, World Development 138 (2021): pp. 10–11.

11 Estonian Open Data Portal, ‘Estonian Land Cadastre’.

12 Hiroaki Suzuki et al., Financing Transit-Oriented Development with Land Values: Adapting Land Value Capture in Developing Countries (The World Bank, 2015), p. 15.

13 Ibid., p. 102.

14 Anne Haila, ‘Real Estate in Global Cities: Singapore and Hong Kong as Property States’, Urban Studies 37, no. 12 (2000): p. 2245.

15 OECD, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, PKU-Lincoln Institute Center, ‘United Kingdom’, Global Compendium of Land Value Capture Policies (OECD Publishing, 2022): pp. 242–244.

16 Marko Tooming, ‘Major Tallinn construction works prove to be millions more expensive‘, ERR, 11 June 2024.

17 Madis Hindre, ‘Vanasadama trammitee ehitus läheb maksma umbes 46 miljonit eurot’ [‘Construction of the Old Harbour tram line will cost approximately €46 million’, ERR, 19 July 2022.

18 Shishir Mathur and Aaron Gatdula, ‘Addressing Barriers to the Use of Value Capture to Fund Transit-Oriented Developments’ Case Studies on Transport Policy 9, no. 2 (2021): p. 512.