Functions in Space or Functional Space?

Why discuss infrastructure? Why dedicate a whole magazine issue to it? Just as Australians cannot but begin each speech with a nod to the original caretakers of the land, no discussion about environment can proceed without a nod to climate problems. These problems have been unequivocally caused by humans. Infrastructure, however, is the basis of everything that humans have created (‘infra’ being Latin for ‘below’). We have created vast systems and networks—global economy, legal system, transport, energy industry, food supply—powered by the machinery of the techno-sphere. Infrastructure has obvious structural faults, which burden our planet and which we are trying to patch up with so-called green policies.

As always, the nature of a thing becomes clear to us when it breaks down. All of a sudden we discover—although perhaps we have known it all along—that the steadfast base structure that we have built stands on shaky ground. To fix something, you need to take it apart, find the fault, correct it, and put the thing back together again. This we can do with, say, an engine or a worn-down piece of furniture. But if the problems are as complex as they are in the case of climate, this sort of analytic method is no longer of use. Things are further complicated by individual worldviews and a large dose of faith. Finding a solution is no longer a mere technical hassle, but requires having a substantial debate and taking a creative approach. Thus, we also must modify our notion of infrastructure, which currently refers to something very technical and artificial, rather than natural and creative.

The design pylon Sookureke located near Mustvee, Estonia is part of the Viru–Tsirguliina 330 kV overhead power line reconstruction project. It connects Estonia to the power grid of mainland Europe. Commissioned by the state-owned company Elering, the pylon was designed by the architectural office PART.

Photo: Gregor Jürna

Infrastructure qua base structure is something that is meant to remain invisible, but at the same time a prerequisite for the functioning of visible things. Bringing the invisible into view is the job of both science and art. The first discloses the nature of things as they are in themselves, whereas the second discloses it via our relation to them. The first is determinate, whereas the second is relative and subjective. Technology tries to eliminate ignorance and incomprehensibility (so that bridges would not collapse, to put it simply), whereas creativity tries to capture what exists in the whole, but does not fit into any equation. In nature, functions emerge as consequences and persist causally,1 but humans complicate their lives by having to plan and give reasons for their activities. This enables ethical thought and holding people responsible for their actions. In this day and age, we cannot simply create beauty that also happens to be more or less functional; rather, beauty is perforce the result of an extra effort—function is primary, beauty secondary. It is not as simple, of course—thinking of, say, a grade-separated junction, we are not concerned with the beauty and ugliness of overpasses, but whether the junction makes life more beautiful, and for whom. We have reached the point where the opposition between technology and creativity has global consequences, not to mention local ones.

Balti Power Plant is the second largest coal-fired thermal power plant in Estonia. It is located about 5 kilometres outside of Narva, a city directly on the Estonian border with Russia.

Photo: Gregor Jürna

Rural infrastructure

The term ‘infrastructure’ was adopted by the French in the 19th century, but our contemporary meaning for it is much more recent. After NATO was established in the aftermath of the Second World War, people began to talk about military infrastructure. Only some time later did the term find its way into the field of planning and design. Today, infrastructure can refer to any sort of system that is necessary for the functioning of something, whether it be material, social, or digital. Most often it is understood as something necessary for securing the economic and social functioning of the society, meaning that it has to do with public interest, and that infrastructure has a certain conflict between the individual and the society already built into it, so to speak. In case of nationally significant infrastructure, it is possible to sneak past both public opinion and the inviolability of private property. Recently, public attention was focused on the extension of Nursipalu training field in South Estonia, which was met with staunch opposition from the locals. The private properties in the way of the training field were acquired by the state under a compulsory purchase order. The locals get compensation from the state, for the government has decided that public interest, which does not necessarily coincide with public opinion, outweighs private interest.

The Nursipalu training area is a military training ground with an area of about 3,300 ha in Võru county used by the Estonian Defense League and the Estonian Defense Forces. The Ministry of Defense plans to expand the training ground to more than 9,000 hectares. The development will require the building of roads and ditches, as well as deforestation.

Photo: Maa-amet

We have reached the point where the opposition between technology and creativity has global consequences, not to mention local ones.

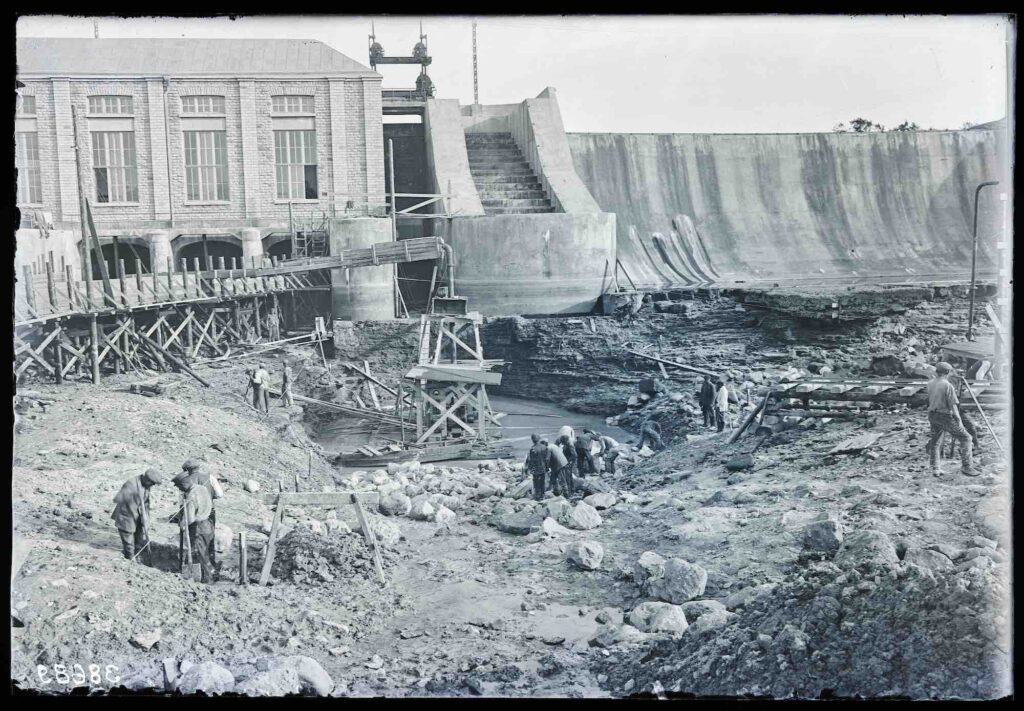

Thinking of spatial infrastructure, one immediately imagines engineering feats that defy the forces of nature, bridge mountain ranges, connect oceans. One spatial infrastructure object in Estonia—again a topical one—is the Linnamäe dam and hydroelectric power plant, where the conflict between energy production and nature conservation concerns is further complicated by cultural history. The dam of Linnamäe power plant has been declared a cultural monument, and thus, it is permitted to continue existing on the condition that the situation of fish is somehow improved. Yet, the Environmental Board refuses to issue such a permit, for the environmental impact of damming cannot be mitigated somewhere else.2 The infrastructure object is preserved without it fulfilling its original function. This in turn calls into question the future survival of the object.

In case of contemporary infrastructure, however, much less heroic facilities come to the fore. The green transition makes it necessary to rebuild the energy system. Renewable energy requires a more dispersed grid and additional connections. All the wind farms and solar farms require connections that can deliver energy from windy and sunny regions to where it is currently needed. On land, overhead power lines remain unrivalled, except in urban areas areas, where the price of land outweighs the cost of moving the lines underground. Overhead lines need to be modernised and the transition to renewable energy also makes it necessary to build new ones. In Estonia, all of this is also related to disconnecting from the Russian electric grid. While existing overhead lines are something that people are already accustomed and acquiescent to, the situation is much more complicated when it comes to building new ones—there are many more disputes. Transmission line corridors are up to 80 metres wide! Estonian system operator Elering has begun compensating for the spatial impact by commissioning design pylons, but perhaps we could reach the point where all new pylons are design pylons and landscape architects can contribute to the arrangement of line corridors.

Linnamäe Hydroelectric Power Station started operating in 1924. In 1941, the station was blown up by retreating Russian troops. The station’s reconstruction project was drawn up by the architect Raine Karp, and

it was reopened in 2002. This year, the Environmental Board refused to issue a permit for damming to the structure’s owner, because it has an irreparable impact on migratory fish and other inhabitants of the river.

Photo: Eesti Ajaloomuuseum

The grid is not the only issue, however—energy production is an even more complicated matter. When planning offshore wind farms, it takes a huge amount of time to work out the environmental impact and cost-effectiveness, not to mention the public opinion. Once again, there are compensation mechanisms. The website of Saare-Liivi offshore wind farm development states that adjacent municipalities will begin to receive a so-called wind turbine recompense. In addition, maintenance harbours and a road network to connect them would have to be developed—thus, the spatial impact of the wind farm for the local resident is much more significant than simply some wind turbines at a distance of 10–50 km. Furthermore, the sea has its own residents: ‘The feeding areas, migration corridors, and the movement routes of fish, birds and bats are investigated in the study. Based on the collected information, the potential impact of the wind farm on the species living and moving through the area is taken into account’.3

Urban infrastructure

In the city, the proportion of infrastructure increases sharply. In the countryside or out at the sea, it suffices if the built facility does not harm the environment—a technicist structure can even appear attractive in natural surroundings—whereas the more urban the environment, the more nature-like our infrastructure needs to be. Most of the public space that we experience in a city is the street network. For some, this is merely a mobility corridor for breezing through in one’s own little air-conditioned environment, whereas for others, this is the main and often the only public space that they can access. Not only is this split dividing the citizens into two opposing camps; in Tallinn, even the municipal government divides the responsibility for these components of public space between three distinct authorities: the transport department, environment and public works department, and urban planning department. The transport department provides the input, the environment and public works department designs and builds, the urban development department takes care of the whole. Sounds simple and logical—first we solve a particular problem, then fit the solution with the environment, and finally learn to live in that environment. However, we remember from the physics class that some equations only apply in a vacuum or some other ideal environment. Thinking only of the function, we will have to learn to live in a vacuum. Yet, this is precisely how the role of the architect is often seen: ’We made an ideal solution; now please decorate’.

By separating function from beauty, we have lost the latter. In classical architecture, the vehicle of beauty was ornament. For the modern man, however, function became so much more important that ornament was declared a crime. As a result, beauty began to be sought in space and form itself. In other words, as Bruno Latour said, we have never been modern—by simplifying construction, modernists made it even more complicated. By breaking down classical architecture analytically into function and decor, neither was purified of the other; instead, this gave way to a hybrid that needs to be simultaneously constructive and decorative, functional and emotional. This sort of hybrid solution works in case of buildings where architects are in charge of spatial design. With infrastructure, this has so far not been the case. However, environmental concerns have now brought it to the public’s attention and called into question the erstwhile practice of ‘let’s just do it’. Although the first reaction has been to replace it with a practice of ‘let’s just do it and decorate it’, henceforth we need to move towards a model in which significant spatial design decisions are made by suitably qualified experts.

Given how expensive it is to build infrastructure, investing in high-quality design is of utmost importance. For more important infrastructure objects, we should consider organising architecture competitions, just like it has been done with main street projects and some bridges. I believe that all the subdistricts in Tallinn would like to have their own main street, their own Vana-Kalamaja. In order to achieve high-quality results, it is first and foremost necessary to ensure the involvement of the architect until the object is completed. After all, we would like to live nicely in a city rather than a functional transport network, right?

Methods and tools

How to ensure high-quality design? Can architects actually design bridges, tunnels and streets while taking into account their environmental impact? If we want to understand the modern city, economy, social relations, or functioning of the organism, the main way to get there is to model it. Here, I do not mean building mock-ups, but computational models, in which we gather all the main characteristic variables, various background conditions, and create a numerical simulation based on them. In this way, one can study the functioning of systems, but most importantly their behaviour in case of changing parameters. If this sounds like something very technical that is practiced by physicists or mathematicians, then yes, that is true, but digitally competent architects are sometimes even more skilled in it. Since architecture is a highly complex field, scientific basis has always been an inseparable part of it.

At the same time, the architect has always been a visionary. Any kind of new technology will be adopted with a dilettantish enthusiasm, which is something that ‘serious scientists’ cannot afford to do. That dilettantish enthusiasm leads to experimentation, however, which in turn leads to new knowledge. Digital architecture is by now anything but dilettantish. The most advanced engineering firms have hired namely architects with digital skills who not only can build simulation models, but also take a creative approach toward them, experiment with them, and reach new kinds of solutions. This kind of creative experimental development has been given a name in recent years—creative research. The strongest aspect of creative research consists precisely in bringing together different disciplines and synthesising them. In the construction field, this sort of convergence is called integrated design, meaning that everyone works within the same computational model. The engineer no longer offers a finished solution, but creates the part of model that analyses and optimises load-bearing structures. At the same time, the architect can modify the form of an object and receive immediate feedback on how this change affects the load-bearing capacity or required amount of materials. Using this method, we at PART Architects designed the pylons of the so-called Bog-Dwellers family, the first of which was the high voltage design pylon Bog Fox in Risti. By now, the family has grown by Bog Crane in Tartu and Little Bog Crane in Mustvee. Although the pylons are different, they resulted from a single computational model.

Elering’s high-voltage design pylons Bog Fox (2020, above), Little Bog Crane (2024, in the header) and Bog Crane (2022, below) are part of a major project co-funded by the European Union. As its result in 2026 the latest, Estonia and the other Baltic countries will disconnect from the Russian power grid and join the continental European grid.

Photo: Elering

Where to next, if at all?

One vision for solving our planet’s most pressing problem—i.e, reducing the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere—is offered by creative researcher, film director and architect Liam Young with his project ‘The Great Endeavor’.4 He visualises enormous processing plants that capture CO2 from the atmosphere and pump it deep beneath the ground. This would create a whole new industry that could be equal in size to the oil industry. Although the construction field has been one of the worst polluters, it could just as well turn out to be our planet’s saviour in the future. At a time when we should increasingly refrain from building new buildings, our living environment will be increasingly affected by the infrastructure for mitigating and adapting to the effects of climate change. For this reason, the tools and tasks of architects are changing—but not our core competency, which is understanding and designing space as a whole.

As the concept of infrastructure has been continuously expanding and becoming more multi-layered, we should take a more versatile approach to designing it. I truly hope that the spatial development agency that is being created will enable spatial experts to contribute to designing nationally significant infrastructure projects, whether it be training fields or (energy) production facilities. In a city, however, it is absolutely indispensable that designing the urban space would also involve an architect who is not merely a rubber stamp. The president of the Estonian Academy of Sciences Tarmo Soomere always emphasises that the future belongs to social scientists. I would add that the future is hybrid, integrated, and complex, and in order to avoid it becoming muddled, we need creative researchers whose strength lies in interdisciplinary approaches. One advantage of computational models consists in bringing together contrasting qualities and parametric optimisation of their relations. In this way, we can accept the proliferation of hybrids, and leave aside the ineffectual distinctions between what is created and what is made, creativity and technology, nature and infrastructure. The important thing is creative calibration of their relations.

SIIM TUKSAM is an architect and creative researcher, head of the research and doctoral program at the Faculty of Architecture of the Estonian Academy of Arts, and co-founder of the architectural practice PART.

HEADER photo by Tõnu Tunnel

PUBLISHED: MAJA 3-2024 (117) with main topic INFRASTRUCTURE

1 Daniel C. Dennet, From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds (London: Penguin, 2017).

2 „Keskkonnaamet keeldus Linnamäe paisutusloa andmisest“, ERR, 29.07.2024.

3 Saare-Liivi meretuulepargi veebileht

4 „The Great Endeavor“, Liam Youngi veebileht