EXHIBITION „OASIS“

Curators: Barcelona-based architect and artist Irma Arribas and Belgian video artist Erich Weiss.

Participating architects and designers: Andrea Zittel, Santiago Borja, Office Kersten Geers David Van Severen, Norma Jeane, Alfredo Barsuglia, Elmgreen & Dragset, Irma Cohen, Tom Hengen, Rummu Adventure Centre and ZA/UM.

8.10.2021-10.01.2022 at Estonian Museum of Architecture

The exhibition ‘Oasis’ held from October 8th, 2021 to January 10th, 2022 in the Estonian Museum of Architecture highlighted how our dreams and desires shape our relationship with the surrounding environment, and hence the society itself.

Oasis is essentially an inhabitable place in the midst of a hostile environment—thus, it has become a symbol of abundance and success. Oasis stands for rest, an opportunity to continue or carve out a new refuge according to one’s wishes. Curators Irma Arribas and Erich Weiss have compiled a set of situations that can be interpreted as oases. Most of the exposition consists of objects of art that relate to space through consumer culture or technological capacity.

The curators do not raise a particular issue or take a clear stance on the contents of the exhibition. Even so, a theory emerges, of oasis as a place or mechanism that shapes our collective dreams and ideas about the relations with the spatial other—that is, how a certain place influences the way we see and think of all the other places outside of it. Familiar spaces shape our relationship with the unknown and foreign—other planets are always viewed in comparison with Earth and mentally rendered similar to our planet.

The oases selected for the exhibition are not depictions of artificial palm trees and pools; in fact, they are not necessarily physical spaces at all, but consist in much more complex situations. This can perhaps be better explained with Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopia.1 While utopia is a place that accommodates an ideal society, but remains merely fictional, heterotopia is a place where utopia has to a certain extent materialised. Thus, heterotopias are simultaneously real and unreal—real because we can abide in them and they are connected with the rest of physical space; unreal because each heterotopia consists of many places at once that reflect and generate all the other known spaces through the ideologies that obtain there.

One example that is presented quite straightforwardly as a heterotopia by the curators is Rummu quarry—a site where a prison, mining camp and adventure centre coexist. The interaction between them forms a recreative space with a wholly repressive background. Thus, the visitor is simultaneously in two different spaces with antithetical meanings. The tragedy of history has been subjected to market-economy based entertainment, thus establishing a new kind of connection between the past and the present. On the other hand, the overlap of a detention facility and adventure centre raises the question about the boundaries between discipline and freedom today.

Oasis of production and oasis of privacy

In our imagination, oases are inviolate fertile places that can be seized either physically or ideologically. These newly-discovered, inviolate places enable us to project our utopias on them—an oasis is able to accommodate our dreams; everything is still possible there. Different types of oases speak of different types of dreams, and help us to understand the impact of such places and ideas on the society. The curators examine one of the major dreams within consumer culture—i.e., abundance—through the lens of modern agricultural production.

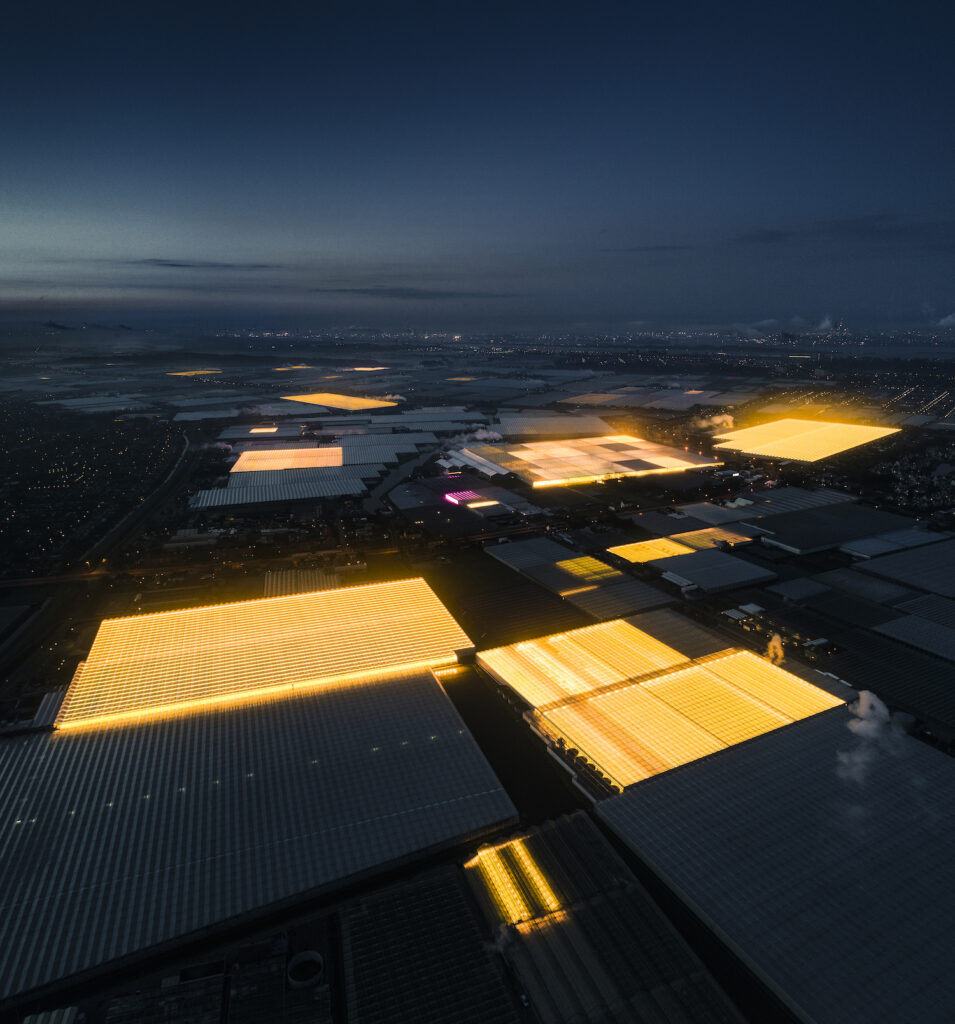

Agriculture is the most dramatic human intervention in the environment. It used to form a part of our immediate habitat, but has now moved to the margins of the urbanised world. Fruits and vegetables are available all year round thanks to concentrated production in the semi-deserts of Spain and suburban Netherlands. The resulting cities of glass and plastic are oases of production and consumption of their own sort that provide us with unceasing output, regardless of the passing of seasons or the fact that they are situated in the midst of adverse spaces such as deserts or logistics-dominated plains.

These sites constitute extremely fruitful and effective production structures that lie in environments otherwise not suitable for us and not expected to be fertile, but which have nevertheless come to offer us what we think we need. High-tech production, building typologies optimised for growing certain specific species and high yields enable the kind of plentitude that has become the norm in the Western world. Uninterrupted availability of produce prompts us to consume even more, which in turn prompts increased production. Cities of glass and plastic, those oases of production, were supposed to fulfil our needs, but the underlying dream of unlimited pleasure knows no fulfilment. Instead, we fall into a vicious circle where the oasis only grows rather than fulfils our needs, all the while enabling us to construct an illusion of overabundance without any consequences.

Shybot (2017), a robot travelling in the deserts of California expresses an even more controversial dream, this time of an antisocial nature—its sole purpose is to be alone. Shybot is programmed to avoid any kind of contact with any living being and to move away from them. It creates itself a reality without any other beings, for its sole idea is to never meet anyone at all.

Shybot fits well with the increasingly encapsulated society that is supported by the kinds of infrastructure and ICT which allow us to evade immediate contacts with others and shape our own autonomous realities. Modern means of communication give us control over with whom and how we communicate. We can choose whether, when and even in what volume someone is allowed to speak. We can choose not to look at our communication partner by shutting off their camera image—whatever we feel the most convenient. Our private apartments, cars and newsfeeds enable us to regulate our relations with others on our own. These technologies can be viewed as oases of privacy that give us near-total control over our relations with surroundings and let us design our own new congenial social reality.

A society where everyone is in full control of their relations with others, similarly to Shybot, cannot work. Inevitably, we belong to a different kind of society, and our attempts to subdue this social reality can only lead to alienation. Consumption that is based on the efficiency of production can meet our dreams only insofar as we do not see the broader effects of this “efficiency”. For the dream to be fulfilled, production needs to take place somewhere far away so that distance and seemingly fantastical technologies could obscure the actual relations between the place and its surroundings.

The politics of oasis

Oases present opportunities to legitimise something that would not be permitted otherwise. In the context of absence and exception, in which we are removed from our habitual space, this ‘something’ can become the norm. A new normality can only be created by moving away from what was before—by changing our environment, going away on a trip, staying in a hotel or summer house.

This is why an oasis always treats the outside environment as hostile—i.e., in order to differ dramatically from what we are used to. A sharp contrast between the oasis and its surroundings renders our dreams particularly desirable, good and reasonable. Any action, any kind of behaviour is fit for the desert. A hostile environment legitimises any activity of ours and lets us realise our dreams of abundance that are actually beyond what the society and world could bear. Our dreams remain acceptable to us only as long as their consequences remain hidden.

An oasis bears superficial or hegemonic relations to its surroundings, cutting off any connections that impede the realisation of the intended utopia and leaving only those that support it. Architecture, too, could be viewed as an instrument for controlling a certain territory. A good example of this is the only work of architecture in the classical sense featured in the exhibition—Solo House (2017) by Office KGDVS. The house is located in pristine nature near Barcelona, reflecting the picturesque landscape that surrounds it. It is a prototype for a new kind of resort—a circular building with a large courtyard in the center. The inner perimeter walls that enclose the courtyard are wholly of glass, whereas the outer perimeter walls are opaque. Interaction with the world takes place entirely via the courtyard.

Solo House is advertised as an opportunity to become one with nature. The building that collects and treats its water and produces electricity might seem environment-friendly, but its spatial relationship with its immediate physical surroundings speaks of something else. The house does not connect with the landscape or vegetation, but showcases and frames human activity instead.

The placement of Solo House within the landscape is reminiscent of Andrea Palladio’s villas of the Veneto. The villas were placed in the highest spot of the plot that offered views of the surrounding lands and agricultural production. The views were always framed by a colonnade or balcony, which bestowed the surrounding territory with meaning, rather than vice versa. Thus, the villas imposed themselves on the territory. The aim was to exude control far and wide, to demarcate as well as reign over the possessions. The villas were built in the 16th century when the focus of Venice’s attention and capital shifted from sea to land. Besides their economic activities, the villas were an intervention that was supposed to show the presence of the patriciate of Venice in the fertile new land.2

The objects on display in the exhibition also bring to mind the headquarters of tech giants, which also follow the logic of the villas of the Veneto in form as well as their relationship with their surroundings. The Apple Campus (Norman Foster) is a large circular courtyard-oriented building complex like Solo House. Facebook’s headquarters is situated amid marshes, on the edge of a nature reserve. The street in the heart of the complex is strictly cut off from the outside world and accessible only to the employees. Its relationship with the outside world is fully virtual and designed by Facebook itself.

In a sense, this type of architecture speaks of a certain way we desire to be in the world—equipped with new technologies in fresh, clean, fertile nature.

Escape into a closed system

All of the above—Shybot, cities of glass and plastic, headquarters of tech giants—are closed and isolated systems that generate a new kind of reality within themselves, but through that reality also shape everything else. Detaching from all confounding factors, they keep to themselves in order to fulfil their social and technological dreams.

They are united in a certain idea of a new beginning. Their visions seem to be built on a hope that material and technological means will make it possible to extract natural resources in a sufficiently clean and efficient way, to take other life forms into account, to integrate them successfully with our infrastructure, and to build new and better cities—in a word, to continue with the current system. All of this is true, but the drawback of such visions (heterotopias) is that they are based on existing cultural and social conditions, which they keep on reproducing—perhaps somewhat more economically than before, but without offering genuine change for the society as a whole. By focusing on technological solutions, we look past the social space around them. Poverty, inequality and alienation remain in the background in these visions. All of the oases presented in the exhibition are clearly bound up with much larger phenomena and processes than it initially seems.

Thus, oasis as a mechanism enables to leave the existing social and spatial reality behind in order to establish a new and better one—one where it becomes possible to think oneself free from the burdens of human society and look past its problems. And yet, ironically, this kind of escape will only magnify everything that one ran away from in the first place.

*

What will become of our dreams? ‘Oasis’ does not show. The curators link together a whole series of issues, but do not offer any solutions. Everything remains open-ended. However, the way we fulfil our dreams spatially and treat our terrae novae or uninhabited areas does not only reflect what we desire, but also who we are. It shows us also what we do not dream of—that which is left out of the dream. As long as we fulfil our dreams by relying on a hegemony over surroundings, as long as we base our technological solutions on exclusive and closed systems, avoiding everything that we find inconvenient, there is no hope of genuine change. Dreams and technological solutions might serve our needs, but they also feed our desires. The way out from this circle does not come from technology, but the ability to find common ground and see a broader (spatial) world behind seemingly isolated desires and dreams.

SIIM TANEL TÕNISSON is a master’s student in architecture in the Estonian Academy of Arts.

HEADER photo by Evert Palmets

PUBLISHED: Maja 107 (winter 2022) with main topic Evolution or Revolution?

1 Michel Foucault, „Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias“, Diacritics 16, nr 1, Spring 1986, lk 22–27. Translated from French into English by Jay Miskowiec.

2 Pier Vittorio Aureli, The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture (The MIT Press, 2011).