PERSONA

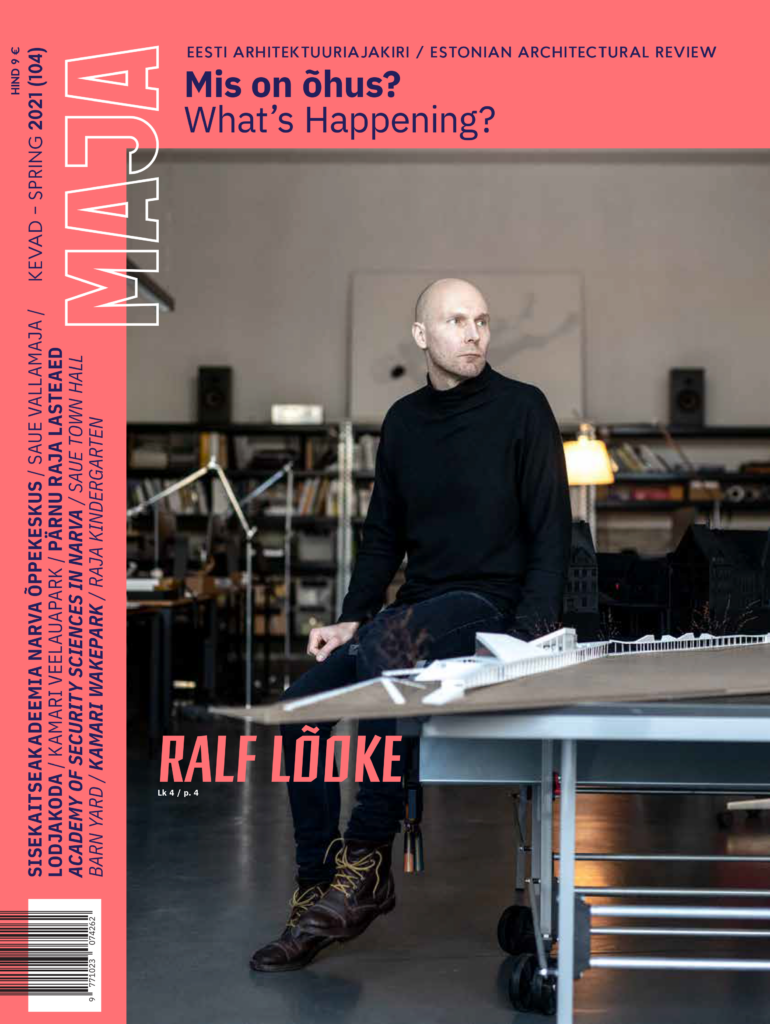

Ralf Lõoke: On Spatial Quality Beyond Excel 〉 Interviewed by Ingrid Ruudi

WHAT’S HAPPENING?

Confluence of Non-Aesthetics and Haute-Aesthetics 〉 Kaja Pae

The Pragmatics and Alchemy of Contemporary Architecture 〉 Ülar Mark

What’s Happening? 〉Kaja Pae, Roland Reemaa, Urmo Mets, Juhan Kangilaski, Andra Aaloe, Keiti Kljavin

Saue Town Hall: Idea and Personality 〉Laura Linsi

A Milky Way of Potential for Creative Space 〉 Madli Maruste

Pärnu Raja Kindergarten. Photo Essay 〉 Paco Ulman

The Wall is a Looking Glass 〉 Helmi Marie Langsepp

In the Long Run We Are All Dead 〉Leonard Ma

What’s Happening?

Amidst the pandemic, everyone is eagerly awaiting for a springtime wind of change, and the question ‘what’s happening?’ has acquired a deeper meaning. The spring issue of Maja takes a tour around Estonia—we will examine buildings in Tartu, Narva, Saue and Pärnu. We conclude our tour near the heart of Estonia, at lake Kamari in Põltsamaa. For several of the examined buildings, alternative designs were initially proposed, and it took many years to arrive at the project that was ultimately built. Despite (or thanks to?) the elongated process, these buildings vividly express something characteristic of our times and manage to spatialise important aspects of what’s currently happening.

Estonian Academy of Security Sciences Narva Study Centre— the largest wooden public building in Estonia and winner of the annual award of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia—is used by three different organisations and has rooms for law enforcement structures as well as those oriented toward public use. The juxtaposition of such seemingly contradictory functions expresses rationality, precision and regional policy necessities of a small country such as Estonia. On the other hand, the study centre is a natural realisation of Rem Koolhaas’s retroactive manifesto for the early 20th-century construction boom era Manhattan, about a culture of congestion where diverse spectrums of functions are brought together, and the articulated result becomes one of the fundamentals of architecture. The study centre has indeed managed to carry out its complicated task with a Nietzschean amor fati, dealing with all the architectural challenges—from environmental sustainability and construction technology to urban space enhancement—in an integrated way. The result feels like the best possible combination that has delightfully incorporated both the good and bad of Narva.

Saue municipal government building experiments on several fronts. The surprising appearance of the wooden building flows quite naturally from the properties of cross-laminated timber and the logic of its use—this mastery of the material already sufficed to earn it recognition as the wooden building of the year. Furthermore, the building has considerable effects on its environment, triggering fresh impulses that could be utilised in designing the emerging Saue city centre. Beautiful use of materials also characterises Kamari Wakepark Building, which the authors have called ‘an almost regular house’. The clean, inviting effect of the materials emphasises the surrounding archetypical elements—water and earth—and offers the guest an authentic environmental experience.

Pärnu Raja kindergarten raises questions about the relationship between creativity and space. Even though educational innovators have been talking about the benefits of diverse and flexible space for children’s creativity literally for centuries, we have yet to heed their lessons. Why? Evidence-based use of space and its effects does not lie solely in the hands of architects, but requires support from other parties. Fortunately, these issues are being increasingly discussed in the society—an example of this, perhaps, is the recent establishment of the Department of Youth and Talent Policy in the Ministry of Education.

Once we have justified the choice of materials and other components of the building, and discussed its place in the urban space, social benefits, environmental issues and everything that is measurable, is there still something left to consider in architecture? In a century hallmarked by urgent global issues, aesthetical matters have often been considered superficial and secondary—and yet, there is a decisive difference between spatial art and a mere building. Perhaps the vocabulary for discussing the aesthetical side of architecture needs to be updated for our complexifying and global world. As long as architectural thinking maintains a strong backbone, its aesthetics will likewise seem forceful and distinctive. Could it be that this possibility of forceful visual expression is the last resort for architecture? We will introduce one of Estonia’s most successful architects of the recent years—Ralf Lõoke, the founder of Salto Architects—and Salto’s recently finished Barge Yard in Tartu. Lõoke’s works have become simpler over the years, but grown in their capacity to speak about abstract issues and express an utmost inner sympathy to architecture by opposing the expected and resisting the orthodox.

Finally, we take a look at Estonian Academy of Arts’ comprehensive three-year study of Tallinn, titled ‘City Unfinished’, which outlines the contemporary landscape of urban planning. Which players should get their turn with urban space today, and how to plan something that is only vaguely in the air and still looking for its spatial expression?

Editor-in-chief Kaja Pae

May, 2021