Healthy Streets in Tartu is a guideline1 providing help for city officials or specialists working on spatial design.

The guide aims at implementing a practice of including previously analysed key topics in street design briefs (in case of both projects and plans) with the contractor obliged to consider the initial data. The guideline allows to base the briefs on the local situation, while the national (recommended but often treated as mandatory) design norms are too universal to be adapted, excessively restrictive and ignorant of the specific local characteristics. Although drawn up on the examples of Tartu, it should be adaptable to all Estonian towns.

Although problems in Tartu are proportionally smaller compared to larger cities, we are similarly concerned about people’s low physical activity, children’s possibilities to move around safely by themselves, the growth of motorisation and suburbanisation. Streets still tend to be treated primarily as vehicle traffic zones that allow pedestrians and cyclists to move in the area left over from traffic lanes. In fact, streets form the most important part of urban public spaces.

People go about their daily business either on foot, by bike or car largely depending on the space where they need to be. All street factors, including the noise, pollution, temperature (urban heat islands) and landscape architecture determine how people feel in the street.

Source documents

In addition to the requirements and restrictions agreed on national and local level, the guidelines also rely on various other materials. The two most inspiring references for the guideline were the street assessment system ‘Healthy Streets for London’2 and the article ‘Measuring the unmeasurable: urban design qualities related to walkability’.3

In the course of the study conducted for the first article, a methodical assessment of street space was carried out. The aim was to measure, among other things, also abstract indicators that all have physical ‘counterparts’ in space. Evaluation of the given indicators helps to identify the individually perceived qualities that make up the often elusive character of city streets.

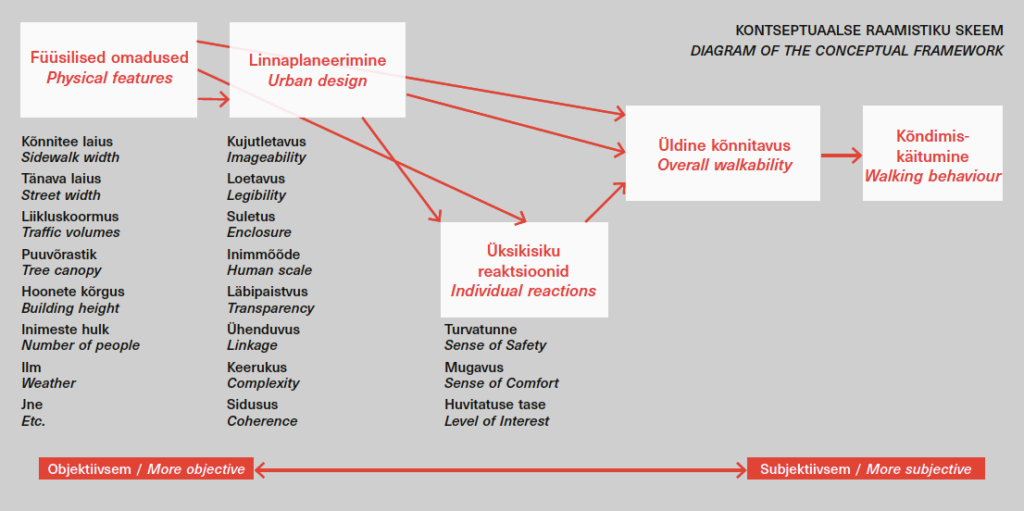

For instance, complexity stands for the visual richness of the place, which in turn, depends on the diversity of the physical environment. To characterise the complexity, the number of people and buildings in the street are evaluated and if there are dominant buildings, conspicuous colours or public art in the street. Out of all the components in the diagram (transparency, human scale, enclosure etc), the guidelines consider the human scale to be the most important one. The diagram below attempts to provide an objective description of aspects encouraging walking.

The structure and applicability of the guidelines

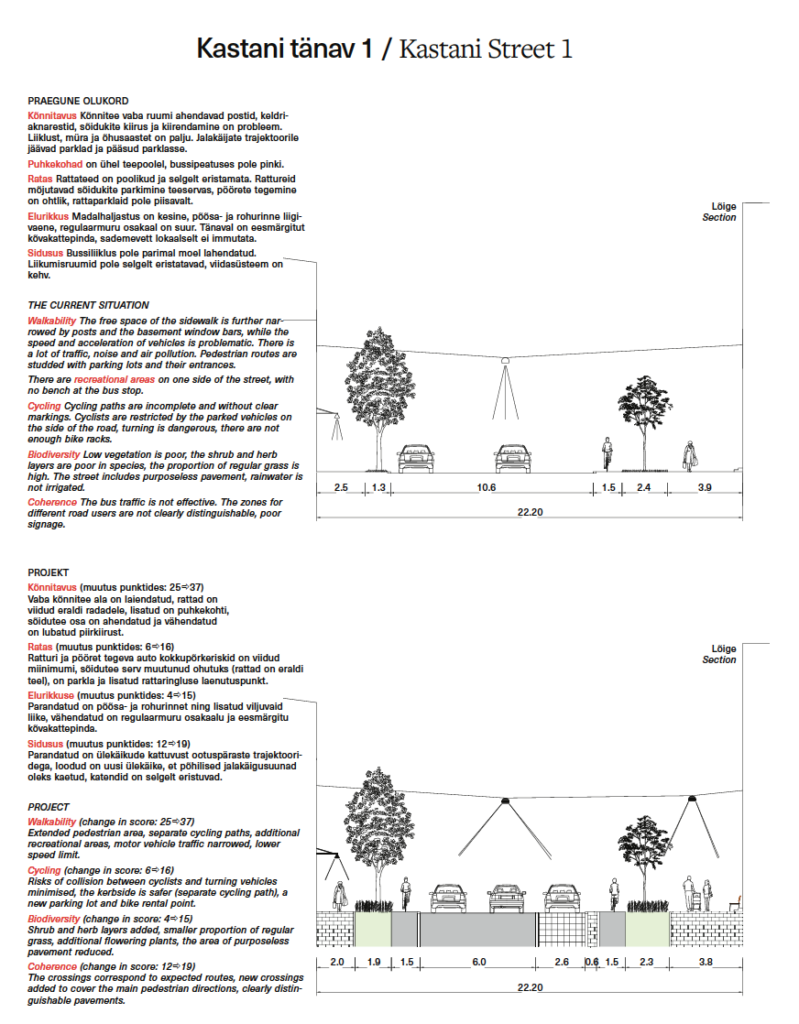

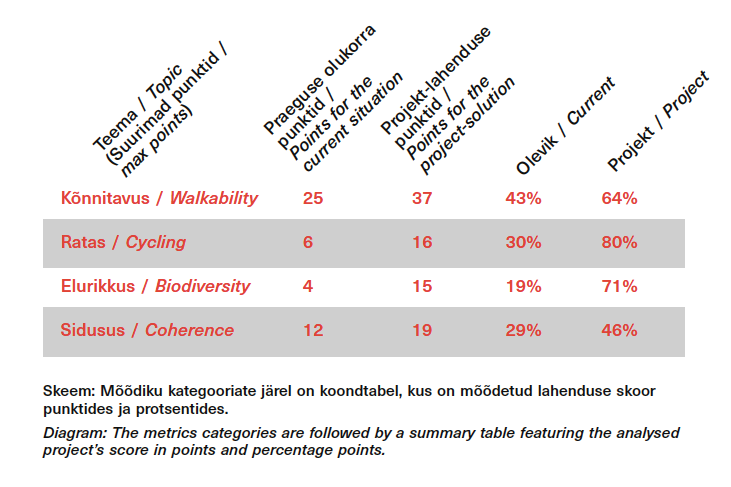

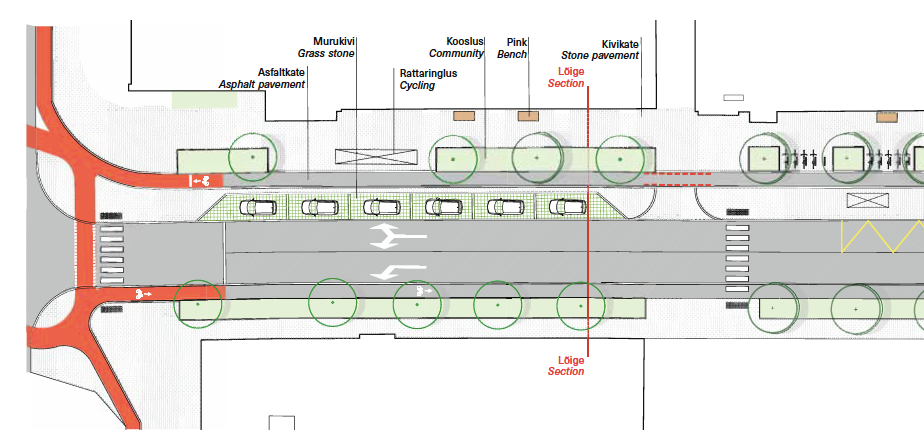

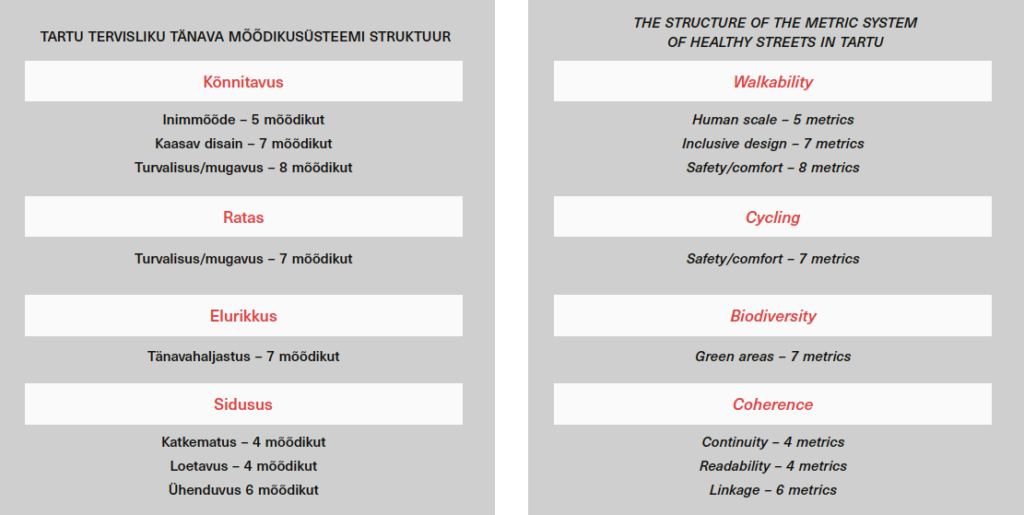

The measurement system consists of four main components that, in turn, are divided into subdivisions each including various metrics.

By answering the questions in the subdivisions, the respective features of the street are revealed. The main and subtopics and questions have been compiled for and adapted to the conditions of Tartu and Estonian towns. The existing and planned situations are evaluated separately.

The main and subtopics are based on the materials analysed while preparing the guidelines. The person-pedestrian (walkability) comes first with the pedestrian mobility in the street space evaluated by subtopics. An important role in walking behaviour is played by senses that mediate the physical features of the environment. Walking experience is the result of the interconnections between the interpretations of past experiences, culture and the perceived environment. The physical environment has a direct and indirect impact on the walking quality by means of senses and perceptions. All factors—physical features, the design solutions of the public space and individual reactions—may affect the way an individual perceives the environment.

Both, the human scale evaluating more abstract components and the safety/comfort reflecting the ease of movement sum up the main sensation felt by a pedestrian in the street. The way a person perceives and feels in the space can be evaluated by various physical indicators of the space. Social field of vision is about 100m—at such a distance, for instance, a person standing at one end of the square can have an overview of the entire square4.

A human-scale urban space is the immediate surroundings perceived by the pedestrian at a restricted distance that is used to classify the perceived surroundings either safely supportive or confining. The first five floors of a building can relate to the street on a human scale, from there upwards, the communication with the city is sharply reduced and replaced by panoramic views, clouds and airplanes. Due to the horizontal perspective, people walking among the buildings are interested in and aroused by the street floors only5. A (commercial) street with numerous narrow building units and doors provides the best opportunities for communication while the doors create several contact points for indoor and outdoor spaces.

Inclusive design allows to evaluate how the needs of (more vulnerable) target groups have been considered. An urban space that is easily accessed by small children and the elderly usually covers also the needs of all interim groups.

The movement of cyclists, positioned second after the pedestrians in the road user hierarchy, constitutes a separate topic. The paramount aspects here are avoiding risks of collision with cars or pedestrians, separation of cycle lanes, quality of the pavement and clear and uninterrupted routes.

The third main issue is biodiversity. The landscaping of street space affects the well-being of people and other species. Already a small green patch can reduce the need for artificial infrastructure for rainwater, provides pedestrians with shelter from rain and sunshine, decreases the soil and pavement temperature etc. Biodiverse street landscaping requires a review of the prevailing trends—in Tartu, there are currently no proper shrub and herb layers, at best, the streets have rows of trees and mowed lawn sections. Assessed pursuant to the given guidelines, most streets of Tartu would probably score low on the biodiversity scale which once again proves that the current practice needs to be overhauled.

The final topic in the guidelines deals with coherence assessing the continuity, readability and connectivity from the perspective of pedestrians and cyclists.

Before the features of the street are measured, it is walked along on either side and filmed from the pedestrian’s perspective. If possible, it is first done outside the rush hour and then repeated during the rush hour.

The Assessment and Analysis of Street Quality

A street or a section of a street that does not feature considerable differences is assessed as one unit.

For the analysis, the clip filmed of the street section is viewed and the respective questions answered. To illustrate how the grade is given, the relevant area is marked in the aerial photo so that the reasons for the grade could be understood later.

Although filmed separately, the two sides of the street are assessed together and considered as a whole. The lower score will always weigh more as it highlights the need for improvement and allows to suggest the necessary means later in the project.

It is important to consider that the final score does not give an exhaustive picture of the street as the nature of different streets vary also within one city district. The score of a street must be viewed in comparison with other similar streets and the suggested solution for the street.

Why numbers?

The term ‘ecosystem service’ was coined around 50 years ago in order to speak to businesspeople in a language they can understand—numbers. It was necessary to provide tables with numbers to make it unambiguously clear what nature gives to people, how to compute the benefits and include them in business plans. Also our guidelines follow the given principle—to hack into a system lined with norms that improperly organises our daily outdoor life. The attempt to provide a numeric equivalent to the human scale or cosiness seems absurd.

However, isn’t the current practice even more absurd allowing our spaces to be governed by inscrutable norms that instead of improving our life force specialists to create uncomfortable, unfair, unfriendly and unhealthy streets? And we keep following the norms day after day as city officials have nothing better to rely on, also proving the goodness of the space in the project is similarly conducted through norms and numbers. Therefore, similarly to the benefits of nature, we should also calculate, for instance, the percentage of walkability or biodiversity that needs to be improved in the street to make it what it should be: the main artery of urban life where people and pedestrians come first.

KARIN BACHMANN is a publicist and landscape architect at KINO. She has studied landscape architecture and urban design and currently pursues her doctoral studies at the Estonian Academy of Arts exploring the curated biodiversity as mitigation of the global changes in urban environments.

HEADER: Graham is a hyperrealistic human being whose physiology has evolved to withstand traffic accidents. Created for a road safety programme of the Australian state of Victoria. Sculpture by Patricia Piccini.

PUBLISHED: Maja 111 (winter 2023) with main topic Street Unrest

1 The guidlines were commissioned by the City Government of Tartu and compiled by AB Artes Terrae and Kino Maastikuarhitektid. The working group included Heiki Kalberg, Tiina Laineste, Sulev Nurme, Hans Orru, Mirko Traks, Juhan Teppart, Karin Bachmann, Katariina Lepiku.

2 https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/health/transport-and-health/healthy-streets

3 Reid Ewing, Susan Handy, „Measuring the Unmeasurable: Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability“, Journal of Urban Design 14(1) (2009): pp. 65–84.

4 ‘Cities for people’, Jan Gehl, published in Estonian in 2015; p 38.

5 ‘Cities for people’, Jan Gehl, published in Estonian in 2015; p 41.