What is the image conjured up by the phrase ‘the industrial heritage of Tallinn’? Is it the Creative Hub (Kultuurikatel), Rotermann Quarter or perhaps Noblessner Foundry (Valukoda)? Henry Kuningas resorts to outstanding examples to describe the main features implemented in the reconstruction of the industrial heritage in the past two decades.

The industrial city of Tallinn

It may go largely unnoticed, but Tallinn is in fact densely packed with industrial constructions stemming from various periods of industrialisation starting from the Czarist era to the end of the Soviet period. The industrialisation of the city began on a smaller scale in the first half of the 19th century and picked up in the latter half of the century spurred by the extension of the harbour in Tallinn as well as the completion of the railway line to St Petersburg. Several huge and well-known industrial complexes were established at the time: the first premises of Luther timber processing complex along Pärnu Road, factories in Rotermann Quarter, the pulp and paper mill in Tartu Road, the Baltic Station railway factory (current Telliskivi Creative City), Wiegand or Ilmarine machine factory and many other corporations. Industry grew in Tallinn at a feverish pace and thus also the city’s population rapidly increased between the turn of the century and the First World War. The given era witnessed a massive industrial expansion including the establishment of Dvigatel wagon factory, Tallinn power plant as well as the new factory of Luther timber processing complex in Vana-Lõuna Street. A similar boom could be seen in the previously sparsely populated northern part of Tallinn with the construction of ‘Volta’ electric motor manufacturing, Bekker, Noblessner and Russian-Baltic shipyards and Baltic Cotton Factory, while Krulli machine factory moved to its current location next to ‘Volta’ at the turn of the century.

Thus, Tallinn soon became an industrial city with a considerable part of its population made up of factory workers and most of them recently relocated into the city from rural areas. Although the local industry was hit by crisis following the establishment of Estonian independence as the large-scale production that had earlier focused on the Russian market now had to be cut and restructured, Tallinn remained as the most important industrial city in Estonia. It retained its status naturally also after the Second World War when industrialisation became an integral dogma of the Soviet ideology.

Reuse and new-builds

According to the well-known quip, Estonians yearn to live in a private house in the middle of a forest by the sea that is located in the city centre with spectacular views. Such wishes cannot obviously be fulfilled immediately, however, some real estate developers have indeed attempted to provide future residents and tenants with new attractive premises. One such exclusive segment in real estate development is the revitalisation of former industrial complexes. When looking around in Tallinn, it seems that the private sector has already rebuilt the historic factories in the city centre mainly as residential and commercial premises, with a smaller proportion adapted for public purposes. Rotermann Quarter, the gigantic project Ülemiste City in the historic Dvigatel district, Noblessner, the new Luther factory, Ilmarine complex, the factory buildings of Eesti Kaabel and its neighbour Punane RET reconstructed as business centres in Narva Road, ʻRauaniidiʼ factory housing the Estonian Academy of Arts, the power plant of Tallinn reconstructed as the Creative Hub and the Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia—the given industrial heritage objects form only a fraction of the long list. There are various phases of development in the former pulp and paper factory in Tartu Road, ʻVoltaʼ district and its neighbour Krulli complex, the former Luther timber processing factory along Pärnu Road, the rubber factory ʻPõhjalaʼ operating in the historic Bekker port, and the colossal Baltic Cotton Factory in Sitsi Street. So, it seems to be high time for a short interim summary.

Rotermann Quarter: dense, denser, the densest

Housing density could be taken as one of the key efficiency indicators of real estate development—to put in simple terms, the larger the number, the larger the potential profit.

For instance, if the housing density in built-up areas of cultural and environmental value is between 0.51–2.0,2 then the given indicator in the detailed plans for industrial real estate developments is considerably higher. In Rotermann Quarter, for example, where most of the historic buildings are under heritage protection, the housing density is 4.723 and the maximum number of floors is seven at the height of 24 metres.

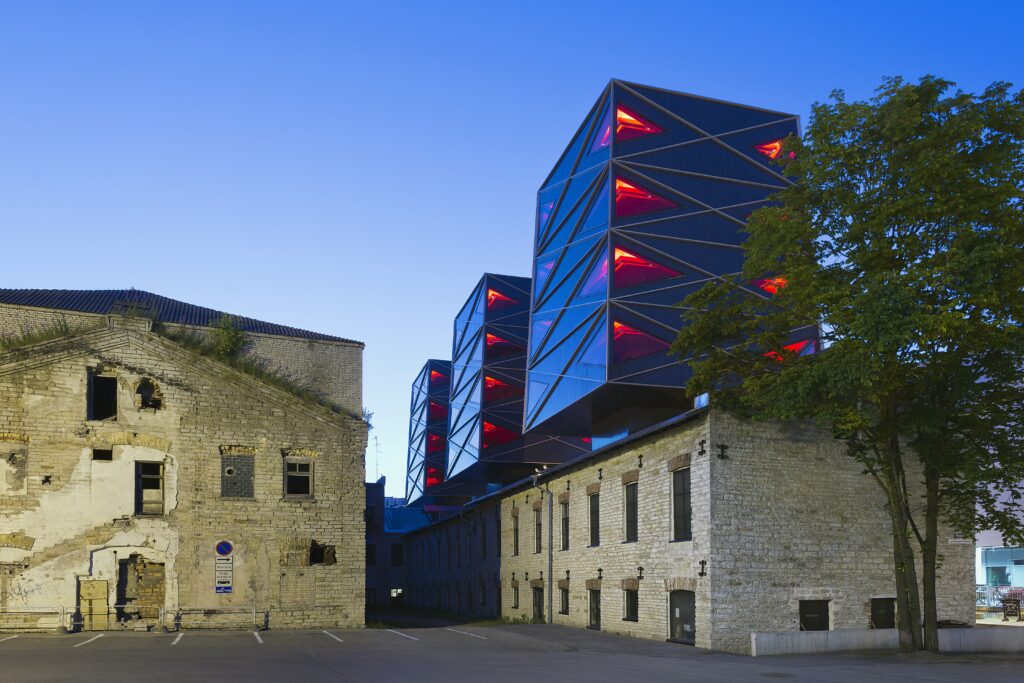

At first, it may seem perfectly reasonable for the city centre. A closer look, however, reveals that altogether five floors were built on top of the two-storey flour mill at Rotermanni 6A in 2014, and four floors on top of the historic three-storey wheat mill next door. It inevitably begs the question of whether it could be considered appropriate for an architectural monument. The most recent example of the trend is the Rotermann Ajamaja building (Rotermanni 6, designed by KOKO Arhitektid, Sirkel & Mall) constructed in 2021 on top of the historical bread factory and office building under heritage protection—a striking architectural solution with a honeycomb glass façade dominating over the historic limestone industrial architecture.

A similar aggressive urban design concept is illustrated also in the detailed plan for the historical mill machinery and wool industry buildings at Mere Avenue 4b (2016, K-Projekt) that have lain unused and abandoned for almost thirty years with only the extension of the parking area on the site of the historical industrial building at Mere Avenue 4a realised so far. According to the given plan,4 the two protected limestone buildings will have a three-level underground parking and 4-5 floors above and attached to it. The explanatory memoranda of the various plans of Rotermann Quarter generally refer to the Rotermann Quarter zoning plan (2002) by Alver Arhitektid that formed the basis for further plans and mainly relied on the following briefly formulated principles: ‘a) the new buildings must remain at least 4 metres from the current facades; b) the maximum height of the new-builds must be 24 metres from the ground; c) the fill percentage 100%’. The conceptual aim of the zoning plan was ‘to create a dense housing that would provide the quarter with its particular identity’. It may be said that the planned density has been indeed achieved, however, in case of many new-builds we do not see the prescribed distance from the historical facades.

Similar wishes to build as much and high as possible can be noted also in the detailed plans for the reconstruction of some other historical industrial quarters in Tallinn. So, for instance, in the detailed plan of the so-called earlier Luther wood processing factory quarter5—between Pärnu Road, Vineeri, Vana-Lõuna and Tatari Streets—on the perimeter of Vana-Lõuna and Vineeri Streets, there are now large-scale 8-12-storey buildings instead of the earlier 2-3-storey constructions. By far the largest of the former industrial complex developments are the buildings already realized or waiting to be realized in the gigantic territory of the former ‘Dvigatel’ factory between Suur-Sõjamäe Street and the airport.

Fresh layers

As to the highly positive aspects about the industrial complex developments in Tallinn, it is definitely worth mentioning some of the examples of distinctive and thrilling architecture and the attractive urban space between them. The new layer has also received a fair bit of recognition, for instance, in 2008, the architecture office Kosmos was awarded the state cultural award for the four distinctive new apartment buildings in Rotermann Quarter, and in 2009, KOKO Arhitektid were the first Estonian architects to be included in the shortlist of the prestigious Mies van der Rohe Award for the reconstruction of the historical carpenter’s workshop at Roseni 7 providing the modest limestone building with three shining towers.

There are obviously numerous intriguing examples of symbiotic sets of industrial heritage and contemporary architecture in Europe, including Silesian Museum built in the former coal mine in Katowice, Poland (Riegler Riewe Architekten, 2013) or the recent cultural centre Maltfabrikken established in the malting house in Ebeltoft in Denmark (Praksis Arkitekter ApS ja VMB Arkitekter, 2020). Although quite dissimilar in their architectural solutions, both reconstruction projects reflect utmost respect for the industrial environment saved for us over the complicated 20th century and also their desire to add a distinctive layer characteristic of our times. In Rotermann Quarter, fans of industrial heritage will most probably feel closest to the reconstruction of the symbol of the entire complex—the elevator building with its mighty windowless walls extending over a hundred metres—that was awarded the best restored building prize by the National Heritage Board in 2016.

Noblessner Quarter: an alternative viewpoint

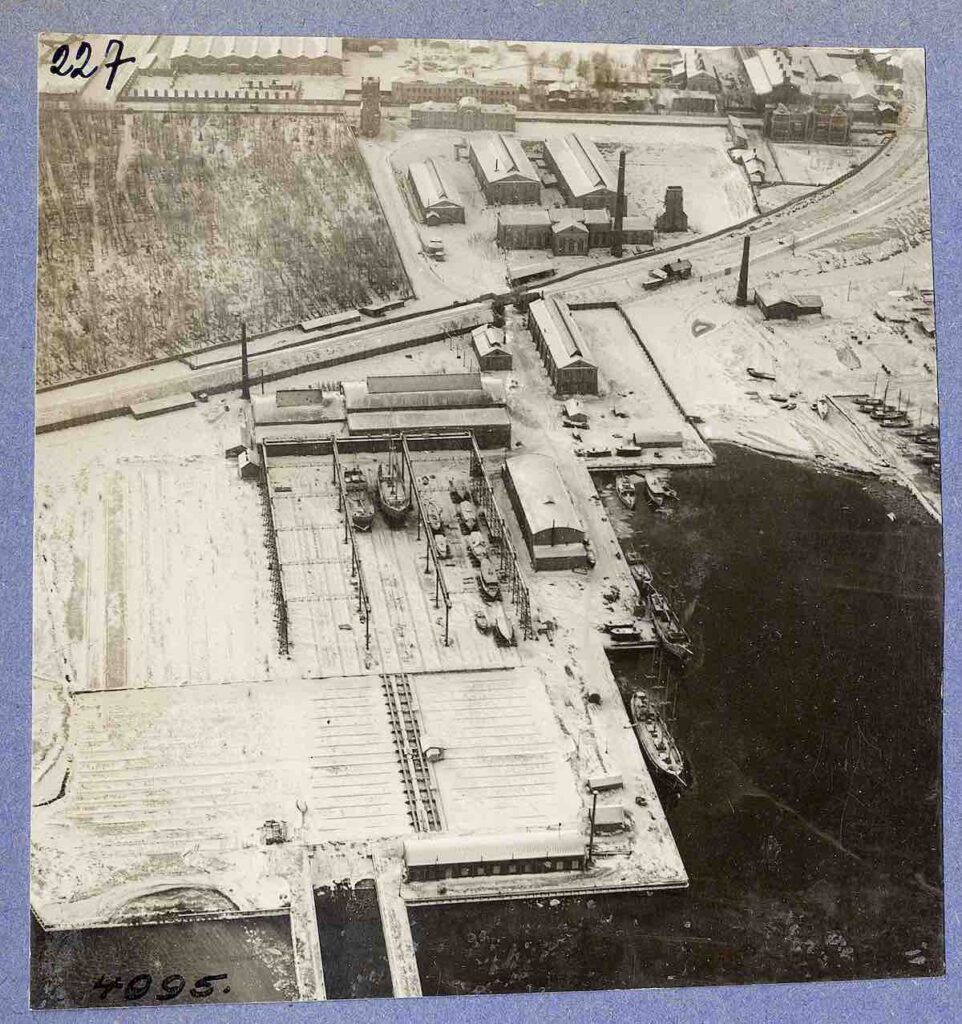

A somewhat different approach is taken by the development of Noblessner Quarter that has similarly enjoyed considerable attention. It was established in 1913 as the Noblessner shipyard and was later known also as Peter’s Shipyard and Tallinn Marine Factory. The former industrial area was gradually opened to the public since mid-noughties. The invited competition in 2007 was won by the Danish architecture office Hvidt & Molgaard with the eventual detailed plan based on their work approved in 2013. Advising the regeneration of the former shipyard territory extending over 24 hectares and its housing, the detailed plan was to consider also the preservation of the fourteen monuments in the area, including the historical slipway. And so it did, there are no extensions or additions to these monuments and the winning entry retained also the airiness around the historical buildings.

Culture as the engine

The first and also the best-known of the development projects in Noblessner Quarter was Valukoda (Foundry) with classical music concerts and spectacular shows performed in the shipyard at Peetri Street 10 and the adjoining foundry already in 2009. The development of the area was somewhat enhanced also by Tallinn’s status as a European Capital of Culture in 2011 with one of its projects including the Culture Kilometre walkway opened on the historical railway embankment. As the path became highly popular among sports enthusiasts, cyclists, dog owners and curious flaneurs, it allowed people for the first time to get acquainted with the area around the railway, including the Noblessner shipyard complex. The car-free Culture Kilometre eventually became so cherished that the construction of Kalaranna Street on its site caused some discontent among the locals.6 Nevertheless, completed in 2015, Kalaranna Street provided a convenient access to Noblessner Quarter and became a catalyst for the development project. In anticipation of the new street, there was also an architecture competition for the new buildings in 2014 won by architecture office Pluss. In 2016, another fruit of positive civic engagement was opened—Beta-Promenade along the sea connecting Kalaranna and Noblessner areas through Patarei Sea Fortress and Seaplane Harbour. The new walkway allowed to link Noblessner better to the rest of the city and thus probably also served as a balm for the loss of the Cultural Kilometre. However, the real gems of Noblessner Quarter are the comprehensively and reverently restored diverse architectural monuments. The first of the buildings restored pursuant to the new concept was the two-storey warehouse with massive limestone walls at Peetri 11 (ARS Projekt), followed by Peetri 3 and Peetri 5 (both by APEX), and the submarine plant at Peetri 12 and the ship building workshop and foundry at Peetri 10 that has become the symbol of the area (both most KAOS), and most recently the historical power plant at Peetri 7 (KOKO Arhitektid).

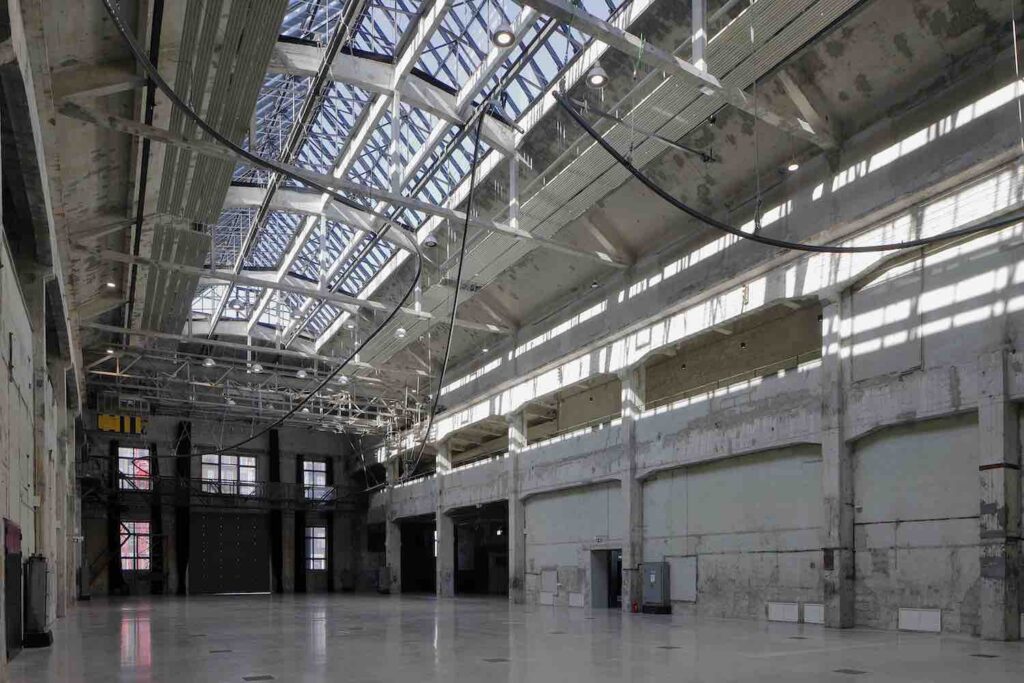

As a welcome exception, the new functions seem to have been fitted into the architectural monuments pursuant to the type and spirit of the buildings and thus there are now shops, restaurants, offices, apartments as well as entertainment venues. So, for instance, the historical battery plant at Peetri 3 has been adapted to retail and showroom facilities, while the adjacent building at Peetri 5 now houses a brewery and a pub thus representing one of the most popular small industry branches of the past decade. The reinforced concrete framework of the plant at Peetri 12 was highly innovative during its construction, and after the gentle, yet firm renovation, it now houses both restaurants and an art gallery. In the eyes of a heritage enthusiast, the indisputable crown of the entire area is the skillful restoration of the historical shipyard at Peetri 10, the adjoining foundry and the nearby chimney. The notional centre of the industrial area is located in spacious rooms accommodating a hall and an entertainment centre. In addition to the numerous historical details and interior elements, the flexible approach to old buildings has allowed to retain the open and sometimes even sacred feel of the interior space characteristic of industrial buildings.

The charm and also the of trouble of historical industrial buildings often lies in their highly particular manufacturing function. That is why it can be difficult to find a new purpose that would be profitable for the investor but also retain the unique interior and exterior features as well as the character and prominent details of the buildings (primarily the equipment and fittings).

***

Today, the diverse industrial heritage in Tallinn has largely been restored or reconstructed and given a new function or in some cases come to its natural end. The ones given a new purpose have a unique history and structure and therefore there are (fortunately) no standardised forms or solutions. Then again, based on the most noteworthy recent examples of Rotermann and Noblessner Quarters, we may say that different goals and methodologies naturally lead also to different results. In short, the focus in Rotermann Quarter is on new attractive architecture while the focal point in Noblessner is the historical industrial architecture. If in the historical buildings in Noblessner, not only the exterior but also the interior of the industrial architecture has been preserved and restored with many of the structures and details exposed, then in Rotermann Quarter, mostly only the outer walls of the historical buildings appearing as stage sets have been retained. Preferring one way to the other naturally depends on the viewpoint and probably also on the perspective of time.

Then again, there are some important and remarkable industrial buildings and complexes that are still preserved and waiting for their development, including the former Krulli and Luther Quarters. Hopefully, their future will give rise to new exciting living and work environments while also preserving the indoor and outdoor appearance of the historical industrial heritage. The charm and also the of trouble of historical industrial buildings often lies in their highly particular manufacturing function. That is why it can be difficult to find a new purpose that would be profitable for the investor but also retain the unique interior and exterior features as well as the character and prominent details of the buildings (primarily the equipment and fittings). It is increasingly complicated in case of extensive complexes where it all should be retained on a considerably larger scale.

It is known that the urban space realised today has usually been planned several decades ago pursuant to the principles that were in force at the time but would now require at least a critical discussion if not intervention. The industrial heritage of Tallinn deserves a more sustainable perspective and custom-made solutions that would consider the character and possibilities of particular buildings.

Incidentally, one of the first historical industrial buildings in Tallinn to be given a new lease on life after Estonia regained its independence was Rotermann Salt Storage that in 1996 became the home of the Estonian Museum of Architecture and has ever since been responsible for promoting and developing the Estonian architecture history.

HENRY KUNINGAS is a heritage conservation specialist and a researcher of industrial heritage.

HEADER: Time Building. KOKO, 2021. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

PUBLISHED: Maja 108 (spring 2022) with main topic Opening Tallinn to the Sea

1 The two-storey building takes up 30% of the plot.

2 The 4-5-storey building takes up 40% of the plot.

3 The detailed plan of Rotermanni 14 and its surroundings approved in 2009 (K-Projekt AS). The housing density in the earlier detailed plan by EA Reng in 2004 was 2.7.

4 Based on the draft by KOKO Arhitektid in 2008.

5 Approved in 2016, K-Projekt AS.

6 Kultuurikilomeetrist saab Kalaranna tänav. Õhtuleht, 15.10.2014