When was the last time you saw a pig? Perhaps you have never even seen one in real life? If so, chances are that you never will—since 2015, letting pigs out of farm buildings is prohibited in Estonia in order to prevent the spread of African swine fever. This means that the animals spend their whole lives indoors—their whole experience of the world is confined to built spaces. Coincidentally, this is a symbolic culmination of a century-and-a-half-long modernist effort to make meat production and the animals involved invisible to humans.

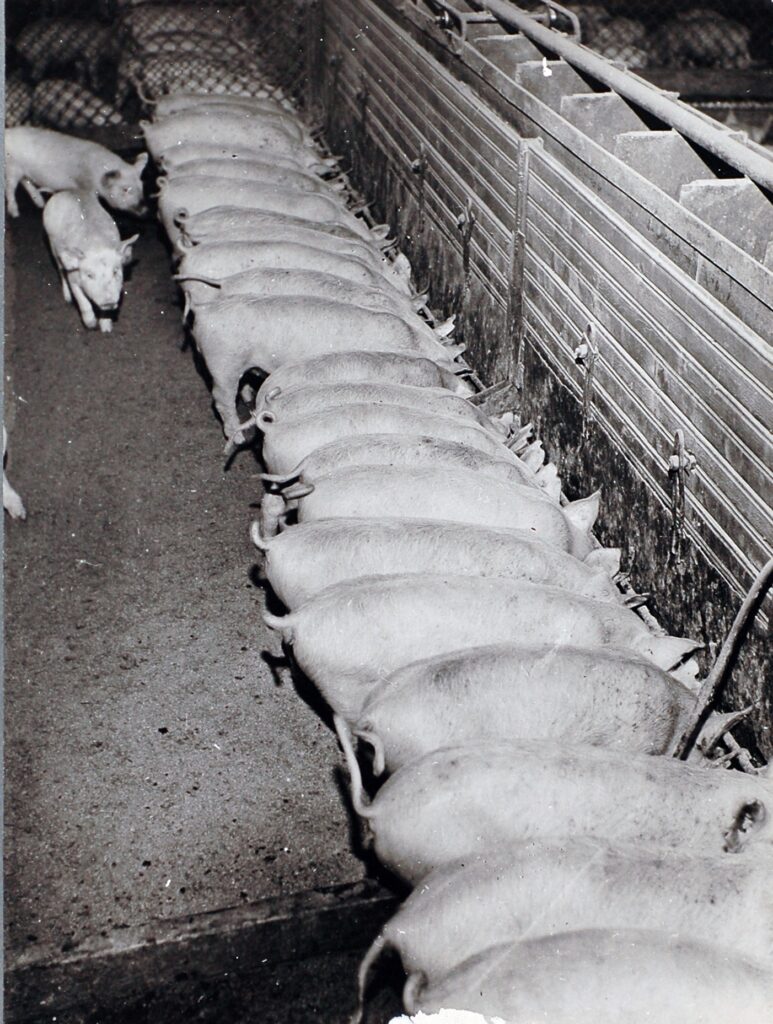

The emergence and development of industrial meat production have played a larger role in the modernisation process than we usually acknowledge. The innovations prompted by considerations of hygiene, cost-efficiency, and effectiveness, combined with changing cultural attitudes towards meat consumption, led to spatial and design solutions that eventually led to the Taylorist conveyor-belt organisation of work. This redefined the modern spaces of labour and consumption, as well as the relationship between the human body and work. Thorough reorganisation of raising farm animals, slaughtering them for food, and the processing, packaging, and distribution of meat began simultaneously in mid-19th-century France and the United States. Although Paris already had five slaughterhouses built outside the city walls in 1818 by order of Napoleon I, the true revolution in the field came with Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s urban transformation project. Between 1863 and 1867, the central La Villette slaughterhouse was built according to his plans. Haussmann himself considered this his most important achievement after the city’s sewage system. Connected to both the port and the railway network, La Villette’s gigantic 56-hectare complex of livestock market and slaughterhouse was meant to house enough animals to supply Paris with a week’s worth of meat and to guarantee clean city streets where butchers no longer slaughtered on site. Thus ended citizens’ complaints about blood running in the gutters, and about disturbing noises and smells, which had been a key issue in the city’s hygiene-related debates alongside prostitution, hospitals, and sewage. However, despite the scale of La Villette, a craft-based attitude and a certain care for the animals persisted—although the spatial setting changed, the practice fundamentally did not. Each animal had its own separate stall, and slaughter took place individually. The complex, featuring neoclassical market halls designed by Victor Baltard, operated successfully for over a century with only minor additions, until it was closed in 1974 and transformed into an urban park based on Bernard Tschumi’s well-known competition proposal.

Creative Commons.

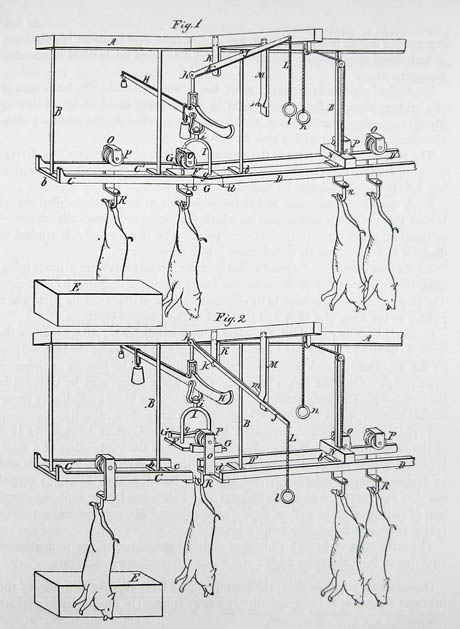

At the same time, a very different kind of development took place in the United States, where the rapid mid-19th century expansion into the Midwest created unprecedented opportunities for large-scale cattle and pig ranching. Huge herds required almost no care on the vast prairies, and there was initially such a glut that only prime cuts of ham found buyers. In Cincinnati— back then the main centre of meat processing—the remaining parts of animals were simply thrown into the Ohio River. Since meat spoils quickly, all slaughtering had to be done in late autumn, and the effort to save time involved optimising the process down to the smallest movements. Given the need to move meat processing to a more suitable colder climate, the fast-growing city of Chicago became the new hub of the meat industry, where in 1865 a centralised meat processing plant called the Union Stock Yards was established. Unlike Haussmann’s La Villette, it was spatially quite chaotic, hastily built of wood with open pens and enclosures—yet organisationally, it was all the more revolutionary. Although an extraordinary number of patent applications was being filed at the time for various rationalising solutions, pigs as living beings fighting for their life did not really submit to machine logic. Thus, the main gains had to come from improving the efficiency of human labour. In the 1860s–1870s, the Union Stock Yards began comprehensively applying the conveyor-belt method, in which each worker performed only one action—bleeding, dehairing, halving, cutting, or packaging—on pigs hoisted onto metal rails by chains and moved through the rooms, the whole process taking less than 24 hours.1 Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted who witnessed it described the men’s hands operating like machines—this fundamentally new way of working had begun to reshape the human body itself. The same scene also inspired Henry Ford, whose first prototype for assembly-line automobile production was based on a slaughterhouse.

John Vachon, Library of Congress, Washington, D. C

Prominent gentlemen walking around in the slaughterhouse to observe it in action was nothing unusual—on the contrary, before amusement parks and cinemas, seeking thrills in the Union Stock Yards was a widespread pastime, and during the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, it was the most popular attraction of the entire exhibition. Even in the 1950s, open tours were held five times a day.2 It was in Chicago that industrial meat production really took off, which Sigfried Giedion has described as one of the quintessential aspects of modernity: the modern slaughterhouse embodies the standardisation, control, and depersonalisation of natural processes.3 In this process, both animal and human bodies are equally subjected to industrial logic and mechanical optimisation.

Although centralised and standardised slaughterhouses hid the unpleasant realities of butchery from modern people’s eyes and ears, the herds that were driven to slaughter could still be seen in the urban space. The next thing to disappear from the meat consumer’s awareness was the rest of the animals’ life cycle—traditional livestock keeping was replaced by concentrated large farms that formed increasingly isolated and enclosed complexes. The development of livestock farming began to be shaped by scientific approaches to feeding, breeding, disease prevention, and control. In the 1930s, artificial insemination was invented, and antibiotics and vaccinations made their way into animal husbandry. All of this was significantly easier to organise and manage on a larger scale, so after World War II, the raising of animals was truly replaced by an industry. Spatially, this meant consolidating and mechanising everything related to the animals’ birth, life, and death, and vastly increasing the volumes. Instead of pastures, livestock farming moved largely indoors, where the animals’ natural life stages and behaviours were simulated with the aim of increasing efficiency. This also had a profound effect on landscapes—by external appearances, the agricultural industry came to look like any other industry; the anonymous architecture of large farms was less and less indicative of what was actually being produced inside.

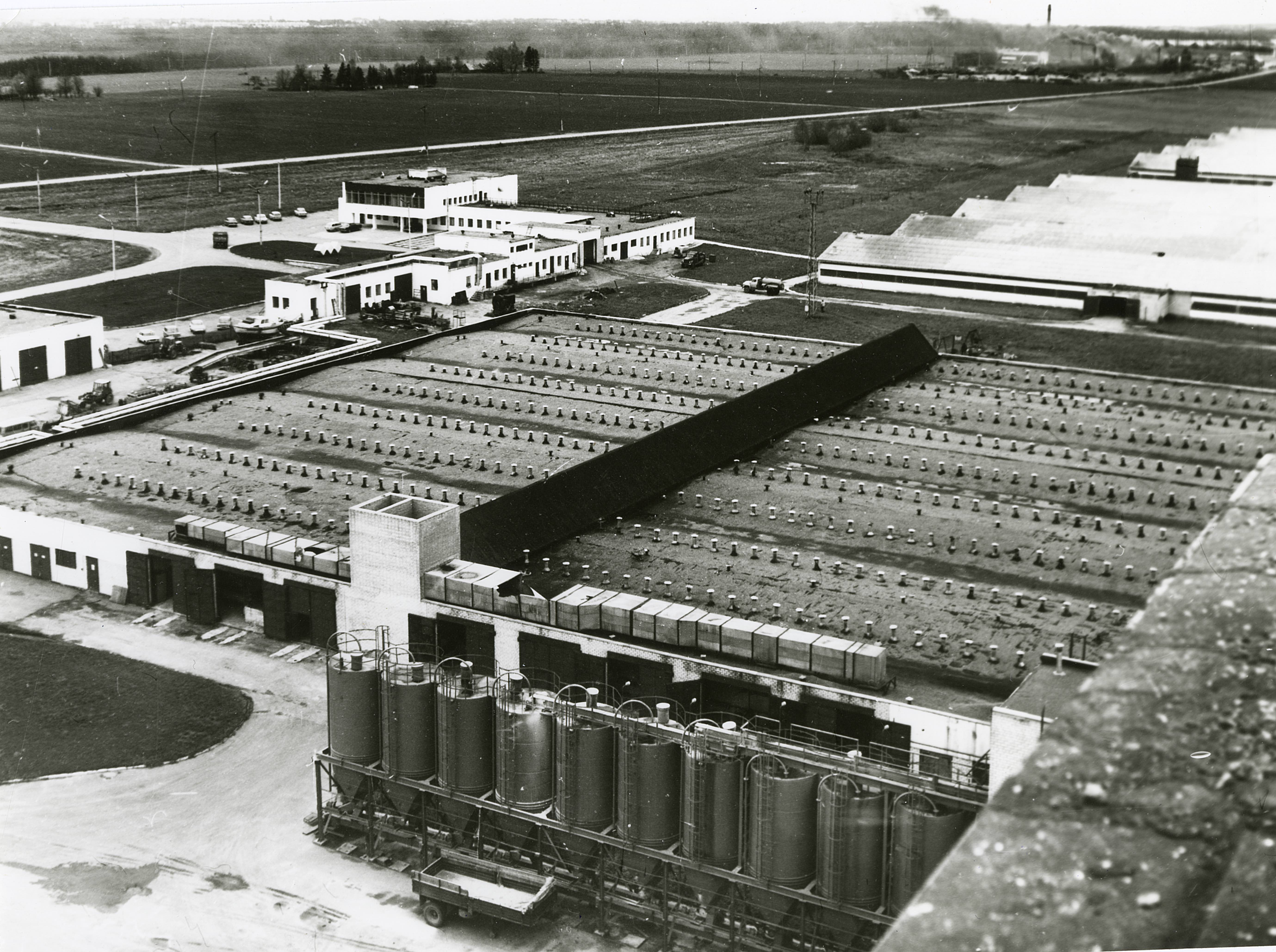

Photo: Museum of Estonian Architecture, Jüri Varus

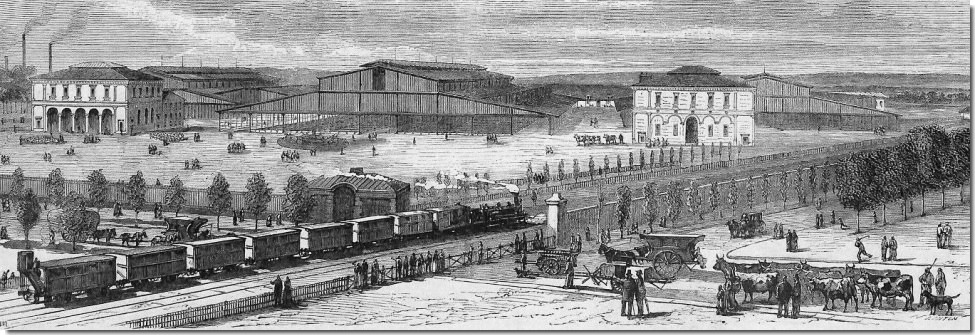

Below: The experimental pig-farming complex in Viiratsi (EKSEKO, 1969– 1973, architect Ain Amjärv, still in operation), which belonged to the J. Gagarin Model Sovkhoz Technical School, housed 52,000 pigs annually. The experimental aspect in both consisted in treating the pig’s life cycle as distinct stages requiring spatial separation for efficient management.

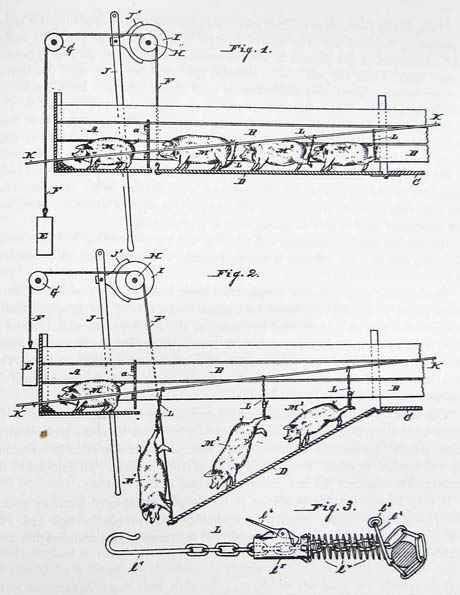

In Europe and the U.S., these processes were driven by capitalist logic, whereas in the Soviet Union, Khrushchev’s agricultural reforms were mostly aimed at overcoming postwar poverty. The aim was to homogenise urban and rural lifestyles4 and this involved establishing large agro-industrial complexes to the countryside. Estonia was considered a supply hinterland for Leningrad, expected to provide meat and dairy products, and therefore the local agriculture was forced towards these sectors with the establishment of several experimental farms. While cattle farming and dairy production remained smaller in scale—typical farms were designed initially for up to 200 cows and in the 1970s for about 300 cows—pig farming was concentrated in two large-scale experimental complexes. The inter-kolkhoz piggery in Jänesselja near Pärnu (1970–1974, architect Ain Amjärv, demolished in 2007) kept 44,000 pigs annually, while the experimental pig-farming complex in Viiratsi (EKSEKO, 1969–1973, architect Ain Amjärv, still in operation), which belonged to the J. Gagarin Model Sovkhoz Technical School, housed 52,000 pigs. The experimental aspect in both consisted in treating the pig’s life cycle as distinct stages (suckling pig, weaned pig, fattening pig, etc.) that needed spatial separation for efficient management, while biological processes such as mating or insemination, gestation, farrowing, etc., were controlled and timed so that piglets were born in uniform batches and the entire herd could be treated as a mass moving uniformly through the production process. After a sow has farrowed and the piglets are weaned, it is taken to the mating section, then onwards to the pregnant sows section with individual stalls, and then to the farrowing section, where the sow is placed in a cage with piglet pens on each side. The piglets can reach to suck on the teats through the bars. The piglets likewise move through the building according to their growth and fattening stages. A fattening pig reaches the required weight of 100 kg in six months and is allotted one square metre of space for its life.

Architecturally, Jänesselja and Viiratsi experimented with different approaches. Jänesselja, sprawling across a large territory, had all of its production and auxiliary lines in separate single-storey buildings to ensure the best internal isolation. By contrast, Viiratsi concentrated everything under one roof in a gigantic six-storey building, in which the necessary connection routes are much shorter, but there is no natural light in most of the rooms. There were also differences in the technological solutions to the main functional problems like feeding and manure removal. It was proudly demonstrated how such a large farm achieved nearly twice the average Estonian production efficiency thanks to its architectural design. Yet although the six-storey building in Viiratsi was functionally innovative and symbolically impressive, the conclusion in retrospect was that multi-storey construction did not justify itself economically.5 On the positive side, manure pollution in these megafarms was at least somewhat controlled, unlike in typical kolkhoz piggeries.

MVRDV.

Even so, industrial meat production appears to be moving (literally) upward. In 2001, the Dutch office MVRDV sparked major debate with its conceptual project Pig City, which was inspired by the startling observation that if all the pigs in the Netherlands were given organic-farm conditions, the required space would be so vast that 75% of the country’s land area would be occupied by pig farms.6 The solution that MVRDV proposed was a concentrated high-rise, where the slaughterhouse in the lower part is topped by a forty-storey fully self-sustaining farm housing thousands of pigs; the exact number was left unspecified, but the 622-metre-tall tower would allegedly feed half a million people. Hence, the Netherlands would need 31 such pig skyscrapers. But although the pigs would have been offered much more humane conditions—more space to move, a chance to live in reasonably sized herds, even balconies for fresh air—the project was seen more as an expression of desperation or absurd science fiction than a serious solution.

Twenty years later in China, such colossal ‘pig palaces’ are no longer science fiction. In 2022, a 26-storey skyscraper farm was opened in Ezhou, Hubei Province, housing 650,000 pigs at a time and capable of slaughtering 1.2 million animals annually. Feeding, temperature, and ventilation are fully automated; robots have taken over part of the caretakers’ tasks, and manure is converted into biogas to heat the building itself. With government support, 170 ten- to twenty-storey pig farms have now been built in Guangdong Province and a couple of hundred in Sichuan Province, but the conditions there are far from MVRDV’s organic utopia.7 In addition to saving land and improving economic efficiency, these megastructures are justified mainly in terms of biosecurity—floors and sections of the building can be completely isolated to prevent disease spread. But the effort to minimise infection risk also imposes rather extreme conditions on workers—they may leave the building (i.e., go home) only once a week, and even then must undergo thorough disinfection and testing.

Photo: New TV China / Globalink

Anthropologist Alex Blanchette, who studied life in U.S. megafarms through extensive participant observation, has described working in such complexes as posthumanist labour, where human bodies, behaviours, and capacities are extremely related to production requirements. The humans in these farms are not just workers but part of a system of risks that needs to be managed; for biosecurity reasons, their lives outside the farm are also tightly monitored and controlled. For example, they are prohibited from sharing a wineglass with friends, and members of one family are not allowed to work on both the ‘life’ and ‘death’ sides of the farm. At the same time, the work is physically exhausting—demanding speed, precision, and monotony—and emotionally draining, as it deals with birth, life, and death. The animals that have been ‘optimised’ to their physiological limits produce very many deformed or overly weak offspring, whom workers help survive with great dedication, performing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, crafting miniature splints, bottle-feeding—only to send them to slaughter a few months later. Blanchette shows how deeply the lives of animals and workers become intertwined in these nearly sealed-off complexes: ‘Somos puercos,’ say the (mostly immigrant) workers, referring both to their shared exploitation and to the forlorn solidarity that arises from it.9

Such megafarm-slaughterhouse complexes encompassing the whole life cycle of farm animals form spatially closed ecosystems of their own, usually in very peripheral locations and as anonymous as possible, revealing nothing of their immense role in today’s capitalist chains. An ordinary person’s encounter with the realities of food production is extraordinarily unlikely; the production process has been successfully hidden and nothing in our everyday visual or spatial experience reminds us of the connection between a living animal and the plastic-wrapped meat product. Even less visible is the extent to which that industry permeates everything. Beyond sausages, pigs provide raw material for over a thousand products: gelatin from skin is found in candies, gum, and cheesecakes; components from lard appear in shampoos and face creams; glue from bones is used in matches and bone meal in porcelain; proteins from bristles soften our bread; manure ends up partly in asphalt. But various ingredients derived from pigs are also used in heart-valve prostheses, medicines, cigarettes, photographic paper, ammunition, biodiesel, and countless other things.10

The history of the livestock industry is likewise increasingly hidden from sight. Old slaughterhouses are elevated into modern cultural centres and creative districts, but in reusing these good-looking pieces of historical industrial architecture, their bloody heritage is mostly hushed up. Teurastamo in Helsinki retains at least a linguistic reference to its former purpose,11 whereas the Shanghai Municipal Abattoir cultural centre soon became Shanghai 1933, and the Old Slaughterhouse Heritage & Arts Centre in Stratford became Escape Arts. These cases, as well as Lyon’s Halle Tony Garnier, Paris’s La Villette, London’s West Smithfield, and Copenhagen’s Kødbyen, exemplify the ‘culturalisation’ of dissonant heritage.12

Large farms and slaughterhouses are not merely functional physical spaces but rather power, control, and violence in architectural form. From the perspective of critical animal studies, they are part of today’s ideological structure, which underpins speciesism and a more general commodification of life. This so-called animal-industrial complex13 at the very heart of modern society is formed of closely intertwined sectors (agriculture, meat production, pharmacology, scientific research, materials development, etc.) that are based on the systemic and institutionalised exploitation of animals. This is in turn based on the hegemony of meat14—a cultural belief system rooted in the idea of humans as dominators of nature, suggesting that meat consumption is not a choice but a normative given. Although most people find the treatment of animals in the large-scale industry to be problematic, they rarely question consuming its products—this is the meat paradox.15

The discomfort is overcome by various emotional coping strategies, such as putting ‘animal’ and ‘meat’ mentally and linguistically in two separate, unrelated categories; making all aspects of meat production invisible in public space; portraying animals in marketing imagery as childlike and anthropomorphic; playing down animals’ capacity to feel; and employing tactics for denying personal responsibility.

Meat consumption has clearly increased worldwide in correlation with overall economic growth. Likewise in Estonia: in 1994, we ate on average 49 kg of meat per person; in 2024, we ate already 78 kg.16 This is roughly equal to the EU average but lower than the U.S. (110 kg), while in India, for instance, annual consumption is only 5 kg. Most of this meat comes from large-scale production; smaller Estonian pig farms have already ceased operations. A major ethical upgrade of society is unlikely to occur in the near future, so demand for meat products will likely continue, and the role of the animal-industry complex as a foundational pillar of the capitalist machine will continue to grow, shaping the sensory experience of life for non-human animals and humans alike.

But to end on at least a bit more idealistic note, let me nevertheless point to an alternative: as of now, four countries (first Singapore in 2020, followed by the U.S., Israel, and Australia) have approved the sale of biotechnologically cultivated meat, grown from animal cells in laboratories. In the U.S., marketing authorisation has been given to five companies. The U.K., the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Spain are moving in the same direction.17 Developing lab-grown meat is part of China’s agricultural five-year plan, and South Korea (where eating lab meat is viewed positively by 90% of the population) is supporting research through favourable legislation and a special economic zone.18 Beyond its ethical benefits, cultivated meat requires far less water and energy, saves an enormous amount of space compared to what is currently taken up both by livestock farms and feed crops, enables a much more efficient circular economy, and significantly cuts down pollution. If we could overcome the paradox of meat and make the hidden realities of the animal industry even slightly more visible, it is conceivable that we might begin inching towards dietary practices that do not require the exploitation of animals.

INGRID RUUDI is an architectural historian working at the Institute of Art History and Visual Culture in the Estonian Academy of Arts.

HEADER photo: Museum of Estonian Architecture

PUBLISHED: MAJA 3/4-2025 (121-122) with main topic WORK AND FOOD

1 Dorothee Brantz, ‘Recollecting the Slaughterhouse: A History of the Abattoir’, Cabinet 4 (Autumn 2001).

2 Ibid.

3 Siegfried Giedion, ‘Mechanization and Death: Meat’, in Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History (Oxford University Press, 1970), 209–246.

4 See also: Mart Kalm, ‘Ons linnaelu maal hea? Majandi keskasula Eesti NSV-s’ [‘Is Urban Life

in the Countryside Good? The Central Settlements of Collective Farms in the Estonian SSR‘, Kunstiteaduslikke Uurimusi 4 (2008): 61–87.

5 Ain Amjärv, ‘Maaehitusest viisteist aastat hiljem’ [‘Rural Construction 15 Years Later’], Ehitus & Arhitektuur 1 (1990): 27–29.

6 ‘Pig City’, website of MVRDV, https://mvrdv.com/projects/134/pig-city.

7 ‘China’s 26-storey pig skyscraper ready to slaughter 1 million pigs a year’, The Guardian, 25 November 2022.

8 Spanish for ‘We are pigs’.

9 Alex Blanchette, Porkopolis: American Animality, Standardized Life, and the Factory Farm (Duke University Press, 2020), 99.

10 Christien Meindertsma, PIG 05049 (Flocks, 2007).

11 ‘Teurastamo’ is Finnish for ‘abattoir’.

12 Yiwen Wang & John Pendlebury, ‘„Uncomfortable heritage“: how cities are repurposing former slaughterhouses’, The Conversation, 27 February 202

13 The term ‘animal-industrial complex’ was coined by Barbara Noske. See: Barbara Noske, Humans and Other Animals: Beyond the Boundaries of Anthropology (Pluto Press, 1989).

14 Amy J. Fitzgerald & Nik Taylor, ‘The Cultural Hegemony of Meat and the Animal-Industrial Complex’, in The Rise of Critical Animal Studies: From the Margins to the Centre, eds. Richard Twine & Nick Taylor (Routledge, 2014), 165–182.

15 Steve Loughnan, Nick Haslam & Brock Bastian, ‘The Role of Meat Consumption in the Denial of Moral Status and Mind to Meat Animals’, Appetite 55 (2010): 156–159.

16 ‘Eestis toodetakse 71% siin tarbitud lihast’ [’Estonia Produces 71% of the Meat Consumed Here’], Bioneer, 17 April 2025.

17 Andy Coyne, ‘Protein pioneers: the countries that have approved lab-grown meat’, JustFood, 19 June 2025.

18 Anay Mridul, ‘South Korea Inaugurates Regulation-Free Special Zone for Cultivated Meat Development’, Green Queen, 1 May 2024.