Ingrid Ruudi discusses architects’ relationship with time and the various ways in which architects in their later years record their doings as history.

Architects have a very specific relationship with time. A keen eye for the present is an obvious prerequisite, but designing and imagining new spaces actually requires mentally projecting oneself in the future. At the same time, there should—ideally—be an equally good understanding of the past—of how time and circumstances have shaped the kinds of spaces that we currently have. The need to operate simultaneously in different temporalities can even feel slightly schizophrenic. What is, in fact, a work of architecture, and when? Right now, when it exists only as a design? In the future, when it will be built? Even further in the future, when it would become inhabited? Let us not even speak of the megalomaniacs who considered architecture in the perspective of a thousand years, including its eventual state of ruins. If we add to this the inevitable slowness of architectural production—a number of time-consuming circumstances that do not depend on the architect and can sometimes even halt the process for months or years—then it is no wonder that an essential part of the profession is a need and effort to gain control of time. Just as designing requires a certain bird’s-eye view of the future, architects are also keen to take care, and take control, of how their work is recorded in history.

Andres Alver recently marked his 70th birthday with the book AA. Arhitektuurist [AA. On Architecture], which presents itself as a hitherto unpublished catalogue of a survey exhibition held in Kuressaare a couple of years ago. In essence, though, it is a 400-page glossy photobook that brings together a selection of designs, competition entries and built projects, which are, with a few exceptions, from the last couple of decades. In this sense, it is not really a summary of lifetime’s work—after all, there was also an interim summary, published in 1999 together with Veljo Kaasik and Tiit Trummal, titled Üle majade. Linnaehituslikke projekte ja artikleid aastatest 1994–1998 [Over the Buildings and Beyond. Urban Projects and Articles 1994–1998]. Nevertheless, AA speaks of choices—of what has been deemed worthy of perpetuation, and how. From his early years as an architect in the Soviet period, he has included only one object, Haabneeme technical centre, which, regardless of its complexity and veritable lavishness, was never completed. For years it stood as a bizarre ruin and witness to its time in the midst of a rapidly developing borough centre, and was finally demolished. But surely Haabneeme earned its place in the book not only for its demolition, but for the nature of the space—it had drama in it, the sort of drama that is present in many of Alver’s designs and which seems to particularly stand out in this publication. In his earlier articles, like those included in Over the Buildings and Beyond, and earlier interviews, Alver has often mentioned the importance Rem Koolhaas’s ideas and attitudes for his understanding of steering urban developments. The present book, however, somewhat surprisingly also echoes Kenneth Frampton, for whom one of the core values was city as a space for public appearance. Alver emphasises that in addition to rationality, cities also need to feature ‘something more’; people oversaturated with virtuality also need real physical experiences, not just random ones but encounters of consciously designed space. In the book, the architect comes across as a great dreamer (the texts that explain competition entries and unrealised designs are particularly rich in sentences that end with the ellipsis) whose mission is to orchestrate the big picture. ‘A comprehensive composition is something to pursue,’ he writes, and surely this is not an empty formal composition, but a spatial setting full of polyphonic activity. In such a vision, the urban space appears as outright symphonic, the city as one big spectacle.

It is clear that Alver wants to go down in history as a Creator. Instead of narrating his own memoirs or the story of his development, he is opinionated about the contemporary practice of architecture competitions as well as the whole of 20th century; in this sense, the texts speak to us from the perspective of someone who is still engaged in action rather than summing up and looking back. Indeed, architecture is one of the few fields that has not yet been overcome by the cult of youth, but where authority accumulates over time, and ageism does not rule out one’s best works being born late in one’s career. The driving force for the author has been unceasing dissatisfaction—at times, the author states his scapegoats openly; other times, they are left more ambiguous. There seems to be an underlying suspicion that perhaps our city dwellers do not even deserve all that beauty of urban life. The people of the forest do not know how to live in a city—Alver is not the only Estonian architect who has come to this bitter conclusion, but perhaps one of the most stubborn and impatient ones. And although a book as ambitious as this surely aspires for wider publicity, both the visuals and the text make it clear that the author is primarily addressing his own professional community—those who know and understand. ‘The real answer will be given by history,’ states Alver when writing about competitions—after all, in assessing their journey and their works, architects do not look to the present day, but rather the macro-scale of time. Architecture is a Sisyphean task, but nevertheless an infinitely optimistic one—sometime in the future, the historical perspective would finally reveal the correct answer, and the good and right solution would prevail.

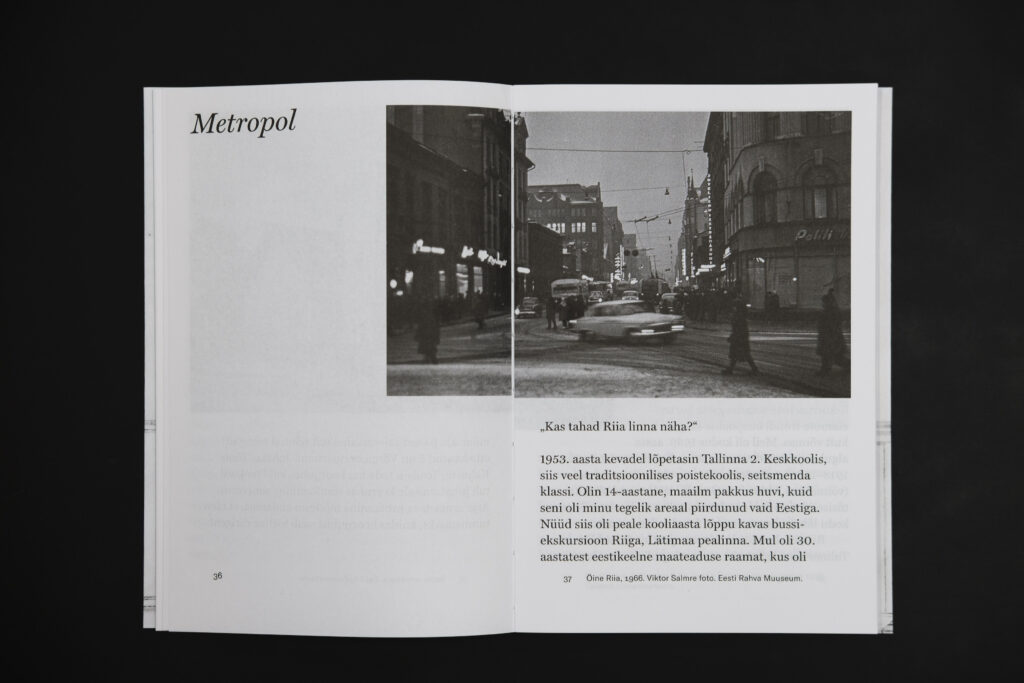

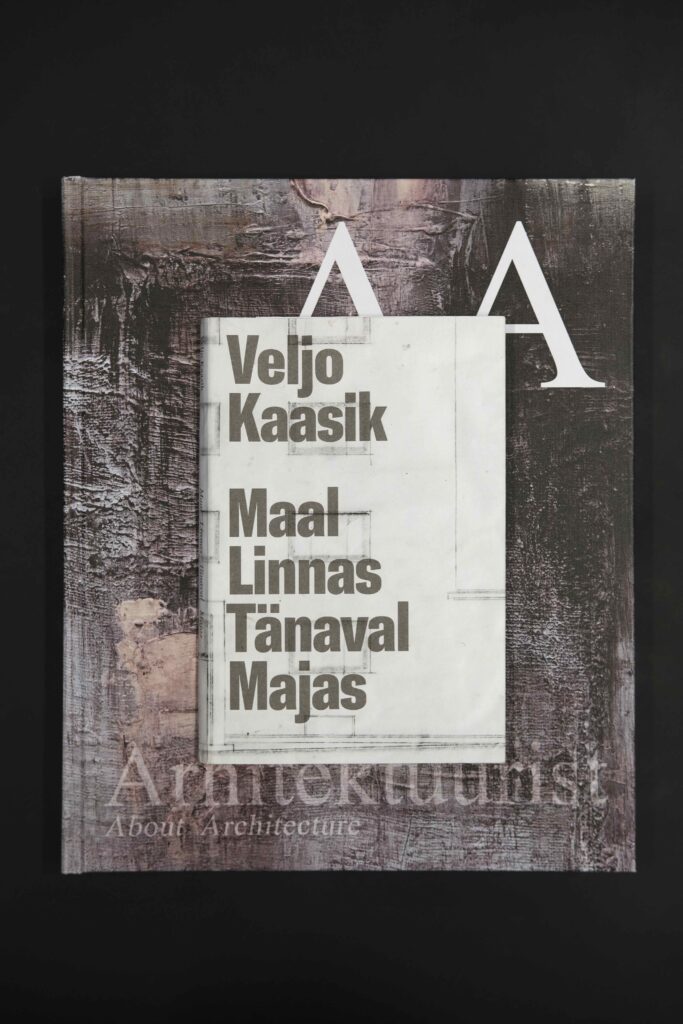

A diametrically opposite way of celebrating was chosen for his 85th birthday by Veljo Kaasik, one of Alver’s closest associates and co-author of several designs. His 2023 collection of essays, titled Maal. Linnas. Tänaval. Majas [Countryside. City. Street. House], is a deceptively modest and slim set of reminiscences with a few black-and-white pictures, plus four previously published papers that still manage to capture Kaasik’s credo as an architect, all the way from his classic 1982 postmodernist manifesto ‘Venturi ja me’ [‘Venturi and Us’] up to his 2007 diagnosis of the woes of Tallinn city centre. The present-day reminiscences are not manifesto-like at all; rather, they are typically Kaasikian observations where the text tends to wander back and forth, and the core idea is often revealed in some indirect way. And yet, the texts still manage to pointedly capture both the contingencies that end up determining one’s life and outlook on the world, and the creative natures of various friends and colleagues. The texts that seemingly ponder over significant moments of childhood or entering adulthood have nevertheless been written from the perspective of an architect, one who paints sensuous pictures of a typically Estonian farm milieu, the waysides, the coast, the spatial experience of metropolis in post-war Riga. ‘A scenario for a road movie,’ said Kaasik himself of his collection, and indeed, the texts are sustained by a sense of capturing something fleeting, something in motion. The amount of texts is just so small that it leaves you thirsting for all the stories untold. But the question that will also linger is, why is it exactly these moments that have gone down as significant? We are left with a resounding beauty of contingency. Even the criticisms of the present day—which Kaasik, too, has plenty of—are embedded in pensive reflections and aimed mostly at oversimplified worldviews and mindless adherence to dull rules.

There aren’t actually that many classic memoirs from Estonian architects. The most well-known one is certainly from Edgar Johan Kuusik, whose perplexingly third-person, but well-written reminiscences present a comprehensive picture of the architect’s own path of development as well as the society and the conditions in the first half of the 20th century, while also bringing into life many other Estonian interbellum architects of whom we would otherwise only know a list of works. Erika Nõva, on the other hand, offsets this with a glimpse of architect’s life from a perspective rather rare for the time and context—i.e., the perspective of a female architect. Nõva’s text is written in a much more matter-of-factly language and can often be incisively frank. The peculiarities of the Soviet period and behind-the-scenes of bureaucratic processes are illuminated to a varying extent in the memoirs of Ülo Stöör, Dmitri Bruns and Raul-Levroit Kivi. Leonhard Lapin’s juicy collection of memories covers in his characteristic manner a whole plethora of fellow travellers from various fields. But with this, the list is more or less complete. Some, like Jüri Okas and Marika Lõoke or Irina Raud, have decided to go down in history with a conventional catalogue of designs, thus ensuring that they will be read in a strictly professional framework; the first two even refused to give a retrospective interview on the occasion of a lifetime achievement award.

On the other hand, the Estonian Association of Architects has been unusually active in recording memories and stories. This has been spearheaded by the association’s section of senior architects, which is in itself an uncommon phenomenon in the context of creative associations, and suggests that architects are vigorously active even in their later years. The seniors see to whether and how the contribution of architects is recorded in history. Since 2007, there have been interviews with architects of the older generation, of which there are already 31 one- to two-hour-long recordings, with 30 more in the pipeline for this and the following year. It is wonderful that there is such an appreciation of oral history of what the conventional written history has ignored, but it also raises all sorts of questions. Whose memories are worth perpetuating? What kinds of questions are worth to be asked? And what for? The project is indeed haunted by a certain lack of focus—the interviews have aimed to capture the whole lifespan and activity of the interviewees without a clear vision of what will become of these recordings. Currently, there is no information about the existence of such a memory vault neither on the website of the association nor the website of the Estonian Museum of Architecture, where most of the interviews have ended up. Fortunately, the community of Estonian architecture researchers is sufficiently small to be able to count on word-of-mouth.

Interview is an intersubjective undertaking—it does not convey a clear-cut pre-existing story, but the narrative is generated in the course of the conversation, in the interaction of interviewer’s questions and respondent’s answers. Thus, the stories collected in the seniors’ project have the character of both the interviewed architects and the architecture historians asking the questions. And that character reveals quite a conventional understanding of what is essential and worth perpetuating in the life of an architect—the questions are mostly about their impetus to choosing the profession, their period of studies and the most colourful teachers, and then in a chronological sequence about the most important, already canonised designs and objects. The day-to-day of architectural offices, legendary colleagues and behind-the-scenes of dealings with the construction committee or the architects’ association are also briefly touched upon. There are always questions about foreign influences, publications that they have read and their travels abroad, thus perpetuating the centre–periphery narrative. We do not learn much about life beyond architecture—the social life of architects (parties, pool nights or tours) is mentioned in passing by only a few interviewees, and some respondents refuse to answer any questions of even a slightly personal character. There are surprisingly few generalisations about the peculiarities of being an architect or architect’s role in the society, or any other sorts of deeper reflections on one’s activities for that matter. Just as rare are attempts to relate to the present day or more generally the afterlife of one’s erstwhile projects—the architectural object is treated as worthy of attention in its original form, as an idea of the architect. On the other hand, looking at the endeavour as a whole and reading the transcripts of these recordings all together, all the occasionally cross-referring stories begin to reveal a picture of architects as a tight-knit, mutually supporting community, whose values and attitudes are surprisingly similar across the board. And although the human side of things can be glimpsed just passingly, the character of the interviewees in nevertheless also revealed by their way of speaking, their gestures, rhythms, pauses and omissions. Even if the structure and questions of the interviews follow well-trodden paths of architectural history, oral history can still give a more polyphonic, nuanced, affective picture.

Similarly, interior architects who probably have even more of a reason to be unsatisfied with traditional history writing, have taken the issue of historicisation into their own hands. Over the years, Taimi Soo and Irena Timusk have compiled thorough folders about fourteen interior architects of the older generation, which are being kept in the Estonian Association of Interior Architects as well as the Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design. Compared to architects, they have approached the task in a more relaxed way—the folders include relatively heterogenous materials; in addition to previously existing interviews or those conducted specially for the occasion, they have tried to gather various design materials, visuals and published media coverage. There is a mix of photos of interiors, social events and childhood. The interviews have likewise a wide reach, sometimes starting with precursory stories about predecessors; the cross-references between the interviews also form an eloquent network. A professional researcher could be somewhat frustrated by the frequent lack of references to the sources of the designs or images, or more generally by difficulties with linking the visuals to the right information. Then again, this is really the charm of the whole undertaking—it is not meant to fill in the gaps left by historians or follow the conventions of archiving, but should be seen as a work in itself, where the process, content and form are equally important elements. As an alternative to mainstream history, this sort of minor archive—a concept derived by analogy from Deleuze’s and Guattari’ ‘minor literature’—does not aim for an opposing, more accurate understanding, but the plurality and hybridity of perspectives.

History writing is a multifaceted endeavour. Over time, through a number of mutually reinforcing individual choices and decisions, a canon is being formed—it is a generally accepted and only partially acknowledged understanding of what is important and valuable in our architectural history. Thus it is most welcome that both researchers and practicing architects are letting their voices and opinions to be heard. But from time to time, it is equally important to have a closer look at those processes and acknowledge what, why and how is being stored in the annals of history.

INGRID RUUDI is an architectural historian working at the Institute of Art History and Visual Culture in the Estonian Academy of Arts.

HEADER: Veljo Kaasik, Maal. Linnas. Tänaval. Majas (Countryside. City. Street. House)

PUBLISHED: Maja 2-2024 (116) with main topic OLD AGE