„A great building must begin with the immeasurable, must go through measurable means when it is being designed, and in the end it must be unmeasured.”

Louis Kahn

Architecture is a practice that operates in an eternal field of tension between the measurable and unmeasurable, where the rational and justifiable materialises in contact with the artistic decisions which are made in the architect’s umwelt and whose internal genesis may often be undefinable and elusive to description. The following is an attempt to shed some light onto that part of the architect’s creative process that is in shadow.

Measurable

We know that at the threshold of making an architectural decision, we face a whole complex of measurable attributes. Hovering above the architect’s desk, one can find the client’s specifications and layout for rooms, the budget, building regulations and planning decisions, climatic conditions, energy balance, technical capacity of the building market, the spatial context of the building and the normativity of the society’s expectations.

An analytical mind can quite adequately assess the functional programming and the expediency and comfort of the room use. It is possible to measure the proportional relations with the surrounding environment and the consideration for the elementary aesthetic context. The assessment of the durability and cost of building and technical solutions is also not a problem. The situation becomes a bit more complicated when one has to assess the building’s novel ways of use or construction, emotional and aesthetic nuances, semiotic gestures, cultural background system, social resonance, that is, its artistic character.

While Louis Kahn who developed a creative credo of his own interpreted architecture in terms of abstract spatial philosophy, the architects of the latest decades have veered towards the measured and fixed ratio in explaining of their works.

The Danish architecture firm BIG has received international acclaim and influenced a huge number of architects over the world with their presentation technique which in its core consists of a step-by-step unfolding of architectural design using simple visual diagrams that are easy to understand. The clever diagrams may easily give a false impression that a particular architectural proposal is indeed nothing but a mathematical analysis of various physical and functional properties and its deduction into a virtuous and right solution. Similar tendencies can also be observed in Estonian public procurements which are dominated by the neoliberal imperatives of functional performance and cost effectiveness. Thus, it also becomes easy to justify the architecture that meets the desired criteria. Yet, we nevertheless know that architecture is so much more than a function of programme, a visual image and a stratification of the material world. What, then, is that which unwittingly slips from our hands, which makes the architecture’s heart to beat and gives it artistic dimensions? Decisions which give rise to spatial experiences—how are they made and what gives them substance? To quote Jaak Tomberg instead of Wittgenstein: ‘Whereof one cannot speak of, thereof one must tell everything.’1

Play and creative impulse

What does an architect think of when not engaged with what is measurable and what can be expressed in words?

Beside and over everything measurable, an unpredictable and unexpected latent field lies, where the architect’s experience and habit operate, along with perception of the moment, creative impulse, or if you want, arbitrary will. It is exactly this latent field which is the territory of the magic and decisive game that can perhaps determine even more than everything else. In the rhizomatous dialogue of factors, the creative decisions are made at the crossroads of the conscious and unconscious—it is exactly at these crossroads where architecture becomes empowered.

Where and how does the playful mind wander? The importance of the play element in culture has been extensively studied by Johan Huizinga: ‘Our point of departure must be the conception of an almost childlike play-sense expressing itself in various play-forms, some serious, some playful, but all rooted in ritual and productive of culture by allowing the innate human need of rhythm, harmony, change, alternation, contrast and climax, etc., to unfold in full richness.’2

The playful mind of an architect is expanded by the tango danced by actuality and possibility, actualising the strings, needles and scissors of inspiration. When an architect works, it means that he or she has received a commission and is authorised to step on the threshold of the possibilities. With the tools at its disposal, a creative mind tries out various architectural possibilities, becomes stimulated and enters the realm of imagination. What has been imagined during a single creative process is immeasurably wider than the path that is finally chosen and refined. Visiting the realm of imagination is often the most enjoyable part of the creative process, lucky are those clients whom the architect invites along to play. When roaming the vastness of imagination, relations are created which, during the play, begin creating meaning. When the meaning is given dimension and shape, architecture is born.

The hotbed of creative decisions is the flirting dialogue between the actuality that is to be accomplished and the realm of possibilities, straddling the border between responsibility and irresponsibility. During the play, a lot of happens that remains hidden for bystanders. Many a client could be aghast upon the realisation that the concept of his or her dream house could be the fruit of a playful mind swimming in a stream of coincidences; spurred by a random recent event, an idée fixe, a further development of earlier creative aspirations or a random subjective emotional observation at the client’s building site, such as an apple tree that evokes the memory of one’s long gone grandmother. Further spice can be added by the fact that the architectural idea emotioned by the grandmother association could be later explained and justified by completely different and rational motives. Probably no architect (or artist in general) is stranger to retroactive interpretation as a means of adding a protective padding of ideas around what is difficult to define. It is no wonder that the architects’ explanations can be full of such standard slogans as ‘opening up best views’, ‘best location on the lot’, ‘allowing space to communicate’, ‘creation of dialogue between the interior and exterior space’. The proliferation of clichés can be indicative of, in addition to laziness, the complicated communicative character of architectural decisions and expression. One cannot also rule out the possibility that the architect simply lacked the courage to admit—there was no architectural idea, there was only an inkling, an affective splint curving towards the starry night sky, or worse, a convenient tonisation of habitual inertia, yet which may nevertheless be securely caught in the safety net of society’s expectations.

Context as a trigger of geometric thinking

Syntax in language and context in architecture perform a comparable role. Syntax/context binds the individual elements into a larger structure, creates a hierarchy of the preconditions of meaning and brings them into focus. In architectural world as well, one does not put a comma between any random pair of words. When building a single-family dwelling, one cannot ignore the presence of an apartment block towering in its immediate vicinity. Here, the context manifests as the riverbed directing the flow of decision-making.

The clients of architecture usually do not understand the context, they are numbed by its unmistakeable presence. Habit is the precondition of adaptation, but it limits the chance of noticing new possibilities. The architect who steps into play sees in the context not a set of spatial elements in a stasis, but a group of dancers who move in timespace and whose position is simply a choreographic snapshot of a dance that is in constant motion and change. Thus, the architect has the power to change the script of the dance and create new possible plotlines, modify the sentence structure and articulation. Regardless of this empowerment, the effect of the context cannot be underestimated—the field lines of the geometric reality put a hidden pressure on the architect’s decisions.

The force empowering the architecture is often indeed the spatial context with all its nuanced characteristics. The context’s particular location is often determined by geometrical power relations—the architect cannot deny the presence of a river, thick woods or a noisy motorway. They all push the gestating architectural idea towards suitable relations and proportions. The space as subject and context tells us itself the way it wants to be. Architecture emerges from the existing spatial plotline. Its influence resides not at all in ideas, but becomes palpable first and foremost in the experience of the tense relations between space and its parts, the expressions of semantic excesses only follow later. Ideas themselves acquire meaning in a semantic aftereffect, when reason interferes with the sovereignty of perception.

The context’s geometric field lines whose presence is strong are not always the sole decisive factor, the scales may also be tipped by a lone and tiny spatial element, such as a 19th century fence or an old vaulted cellar, which represents the relations existing in our collective cultural memory. This is how the genius loci, the spirit of the place, manifests. The context becomes the field which has to determine the meaningful values. In such a situation, the architect makes invisible decisions and determines which elements deserve the preservation and continued enforcement of their meaning and which do not. While mapping the meaningful values, it is interesting to notice the different categorisations of various components. The purely geometric parametres, such as big/small, are complemented by historical, social, emotional, etc. criteria. Perhaps it is precisely the value of the memory of an old well on the lot of a single-family dwelling next to a big motorway that determines the dynamics and contours of an architectural design to be created.

Senses as the basis for understanding the unmeasurable

When trying to comprehend Kahn’s observation regarding the unmeasurability of architecture, we land upon the prerequisites for perceiving the spatial art, where we find the human senses and perception. The feeling of the existing through moving, the bodily sensing or reading of space: information generated by hearing, smelling, tasting and seeing. The architectural internal dialogue is not conducted in a verbal logocentric system, but in the language sensory experience in space. The observations made through experience and memory form a spatial intelligence which guides the making of spatial decisions.3 For Christian Norberg-Schulz and Juhani Pallasmaa, the apologists of the architectural phenomenology, the discourse dealing with experience and perception, the foundation of architectural philosophy lies in the conception of space as an existential relation. Thus, the architectural space is an important ontological category through which the person either knowingly or unknowingly engages in constant self-definition or giving meaning to being through surroundings.

Any architectural space creates a certain emotional register. It can be diversely opulent or narrowly poor. The highlighting of the peculiar character of the light of morning, noon or evening sun by means of architecture creates a rich emotional palette. Contacts of the body with different road surfaces or floor coverings convey through touch warm and cold emotions. When we choose to create rooms with different heights instead of uniform height, we also perceive different registers—small rooms with low ceiling impart a sense of comfort and security while wide rooms with high ceilings inspire awe and instil a feeling of grandeur.

The architectural phenomenology investigates the origin and manner of construction of our collective and personal relations with spatial elements through different senses. Herein lies hidden the psychological character of architecture, the study of which can lead us to a better understanding of the identity of locations. Of these relations, albeit slightly mysteriously, the unmeasurable side of architecture speaks.

Collisions and reconciliation

Speaking of the measurable and unmeasurable, we can be easily caught in the opposition of materialism and idealism. Moreover, such a balancing act on a tightrope is indeed the part and parcel of an architect’s everyday work. The rationalists condemn and jettison the creators who focus on experience and ideas, the latter, on their turn, brand as formalists and narrow-minded everyone whose grasp does not extend beyond the organisation of the pragmatical and technological. While the vanguard of contemporary architecture busies itself in the service of technological progress and realises its world-saving self-expression through parametric modelling and algorithmic design and innovative production technologies, we also must keep delving into the psychological fundamental relations between humans and space.

Why does Kahn think that a building must in the end be unmeasured? After all, the architectural phenomenology insists that, if we really want it, by analysing experiences we can deconstruct and make visible and measurable even the more abstract relations. The different branches of spatial psychology indeed seem to be hard at work at uncovering such relations. We will explain Kahn in the words of our local master Edgar Johan Kuusik: ‘A true work of art refuses to reveal all the secrets of its effect, since its effect is very often indeed based on what it does not reveal directly/…/therein probably lies the building’s irrational element which we are capable of perceiving only through experience.’4

Regardless of which future awaits us, the one where computational architecture only sells because its mathematical models are measurable or the one where the manipulation of physical space is based on behaviourist discoveries, in this conflict, the only option should be the reconciliation between the two sides of human brain. Before making any sweeping claims, it may be instructive for an architect to build one of his or her designs and for a pragmatic builder to live a few years in a building drafted by an electrical engineer from the next door.

URMO METS is a partner of the architecture office Kauss Arhitektuur and a practicing architect whose other activities include music, art and creative writing. 2017 saw the publication of his book Võimalikud majad. Conceivable Houses by paranoia publishing group ltd.

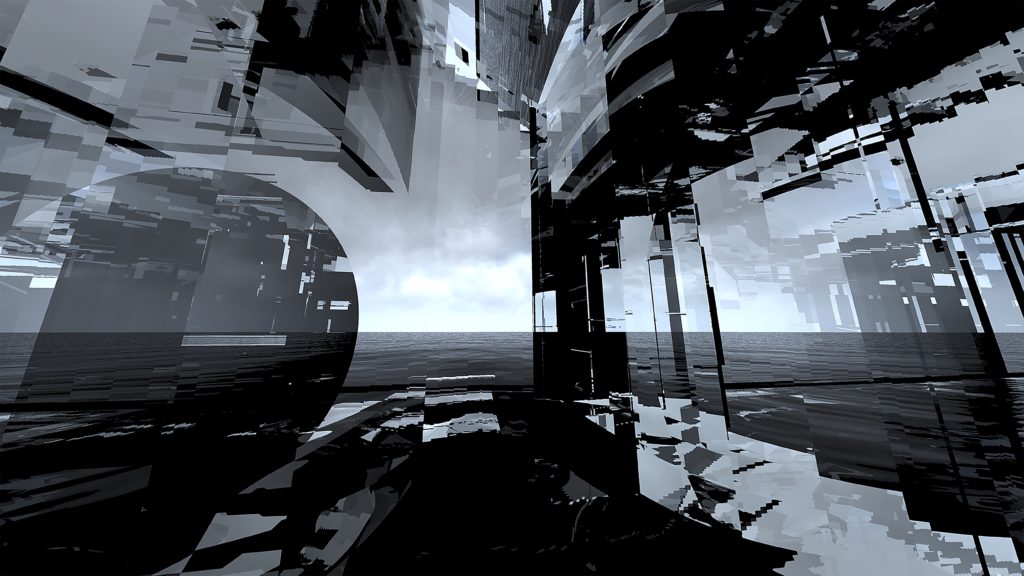

HEADER photo by Lauri Eltermaa. Rendering errors, 2013-2017

PUBLISHED in Maja’s 2018 summer/autumn edition (No 94).

1 Jaak Tomberg, Millest ei saa rääkida, sellest tuleb kõnelda kõike [‘Whereof One Cannot Speak, Thereof One Must Tell Everything’] in Estonian cultural weekly Sirp 04.12.2009.

2 Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture (Routledge 2003), p. 75.

3 Leon Van Schaik, Spatial Intelligence: New Futures for Architecture (John Wiley and Sons Ltd 2008).

4 Edgar Johan Kuusik, Ehituskunst [‘Architecture’] (Valgus 1973), p. 196.