Designing with a territory values connection over extraction. Clara Kernreuter from Atelier LUMA and Maria Helena Luiga from kuidas.works discuss bioregional design.

Reclaiming the bond between design and territory

‘Here in Arles, we have rice fields, pastures, Aleppo pines, limestone, and red sandstone. So why are our neighbourhoods built with cinder blocks, PVC, plasterboard, and rock wool? The question seems naive, but it speaks volumes. It reveals a gap between territories and those who develop them. It points to the amnesia caused by the global standardisation of materials, techniques, and the skills they entail. It tells a truth: we no longer know how to ‘inhabit’ our territories. In our Western societies, the act of building has been homogenised, erasing the distinct textures and identities that once tied architecture to its territory. If we want to bring production and territory into harmony again, design, like architecture, cannot simply evolve along the trajectories of technological progress or global trends. We must recontextualise design and face up to what this implies: breaking with the extractivist model, inherited from mass industrialisation and productivist colonialism, which is still active under the guise of neoliberal globalisation. It is in this context, where the habitability of territories is being questioned more than ever, that the term ‘bioregional design’ takes on new importance.

LUMA Arles hosts exhibitions, site-specific projects, commissioned works, and extensive archives of artists and photographers. Atelier LUMA is the design research lab of LUMA Arles, exploring how local materials, resources, and skills can inspire more sustainable design and architecture. The team has helped develop materials and products for the transformation of the Parc des Ateliers and led the renovation of the Magasin Électrique, a former industrial building that has now been turned into a workspace, research hub, and exhibition venue.

Photo: Atelier Luma, Maria Lisogorskaya

Bioregionalism is a concept that emerged in the 1970s in post-hippie California, driven by radical ecological movements encouraging local autonomy in the face of industrial society. In their 1977 article ‘Reinhabiting California’, Peter Berg and Raymond Dasmann, founding figures of the movement, call for the ‘reinhabitation’ of territories.1 Their essay not only advocates a return to nature, but also criticises modern fragmentation, which separates spaces of production and use, political decisions, and ecological realities. The bioregion is described as a territory delimited not by administrative boundaries, but by relatively homogeneous ecological characteristics (watersheds, geology, geomorphology, climate, living ecosystems, etc.). But it would be simplistic to believe that these divisions are purely ecological. According to landscape architect Robert Thayer, bioregion is the most logical place and scale for the sustainable and invigorating establishment and rooting of a community.2 A bioregion, therefore, is also cultural and social. The communities that live there develop their identity, practices, and narratives in direct connection with the resources and constraints of the territory.

For designers seeking to put this concept to the test on the ground and break off from the logic of globalised standardisation, the bioregion serves as both an operational framework and an analytical tool. ‘Bioregional design’, then, is not a method to apply, but an ontological shift: designing no longer on a territory, but with it. It requires an ethical stance and demands stepping out of the role of the ‘author-designer’ to assume that of ‘designer-mediator’, ‘designer-connector’, or even ‘designer-inhabitant’. It also entails recognising that the production model itself matters as much, if not more, than its concrete application.

Photo: Atelier Luma, Jean-Baptise Marcant

Materialising the bioregion: Arles and the Magasin Électrique

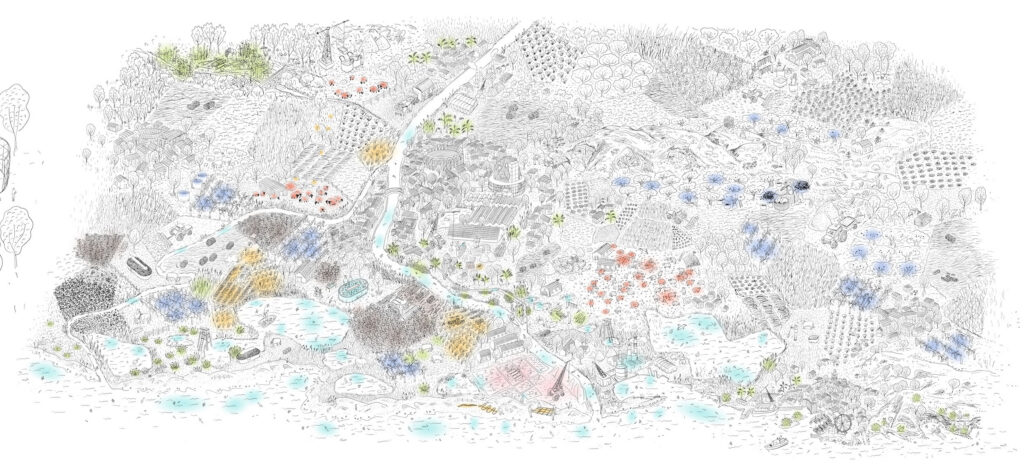

Since 2016, Atelier LUMA in Arles has been seeking to test bioregionalism on the ground. Its interdisciplinary team of designers, architects, and researchers explores local, non-extractive material production from invasive plants, agricultural by-products, algae, and industrial waste. Working as a collaborative platform, Atelier LUMA engages with collaborations with stakeholders such as farmers, craftsmen, cultural actors, manufacturers, and laboratories to design solutions grounded in ecological and economic realities. Rooted in the bioregion of Arles, the Camargue, the Alpilles, and the Crau, Atelier LUMA has gradually extended its reach to other regions of France, Europe, and the Mediterranean, adapting its approach to diverse landscapes and challenges.

The first architectural realisation came with the renovation of the Magasin Électrique in 2023, in collaboration with the architecture studio Assemble from London and BC Architects & Materials from Brussels. Repurposed as a workspace, workshop, and exhibition venue, the building functions as an ‘active archive’ of its bioregion: raw earth, rice-straw insulation and acoustic panels, sunflower-stalk plasters, tiles from waste clay. Beyond materials, it demonstrates a way of engaging with a living territory, revealing its flows, its tensions, and its potential. Design began with field investigation: walking the landscapes, mapping material flows, listening to the locals. As sociologist Bernard Picon notes, the Camargue is a ‘landscape built by agricultural engineering’,3 dominated by monocultures such as rice, whose straw is often burned in a destructive practice called écobuage; sunflowers, whose stalks go unused; Arles’ merino wool, once vital but no longer economically viable. From these realities, the team sparks conversations, surfaces controversies, and imagines alternative scenarios.

Photo: Atelier Luma, Adrian Deweerdt

Designing new materials is never purely technical. Performance and environmental impact can be measured, but social, cultural, and economic consequences of emerging supply chains remain uncertain. Should sunflower by-products, for instance, be used despite their origin in an industrial monoculture? Design in this context demands embracing uncertainty and variability: variability of resources, their cycles, ideas, and decisions, which requires inventing adaptive production systems beyond industrial standardisation. In this context, architecture becomes a tool of mediation. Sites transform into spaces for dialogue among designers, farmers, technicians, and public authorities. The goal is not just to produce materials but to cultivate a shared and common culture, exchange knowledge, and train both designers and builders.

Photos: Atelier Luma, Assemble

We have to admit that the Magasin Électrique emerged in a privileged context, made possible by LUMA Arles, whose funding and proximity allowed the team to work directly alongside the construction site, enabling on-site prototyping and a two-year period of experimentation and residencies before construction began. Yet such demonstrators are crucial. They inspire, provide proof-of-concept, and help structure networks, supply chains, and collaborations that make future projects more feasible.

This can be in seen with the recent Clinique Paoli renovation project in Arles, where, using the materials developed for the Magasin Électrique and the same craftsmen, the total cost of construction was already halved thanks to the established knowledge, chains of production, and the craftsmen being experienced in application. Bioregionalism unfolds through iteration: each project, each building clears the path for the next one.

Photo: Clara Kernreuter

Bioclimatic assemblies: building with reed and earth across climate zones

In the Magasin Électrique, where Atelier LUMA’s work continues to explore bioregional material design and research, we launched in 2025 a new territorial study titled ‘Reed × Clay’ as part of a six-month research fellowship awarded by LINA, an EU-funded platform, and carried out in collaboration with the Tallinn-based studio kuidas.works. kuidas.works is a research-based architecture and building studio founded in 2021. The studio explores ways of giving value to mineral excavation waste from building foundations and producing local, earth-based construction materials.

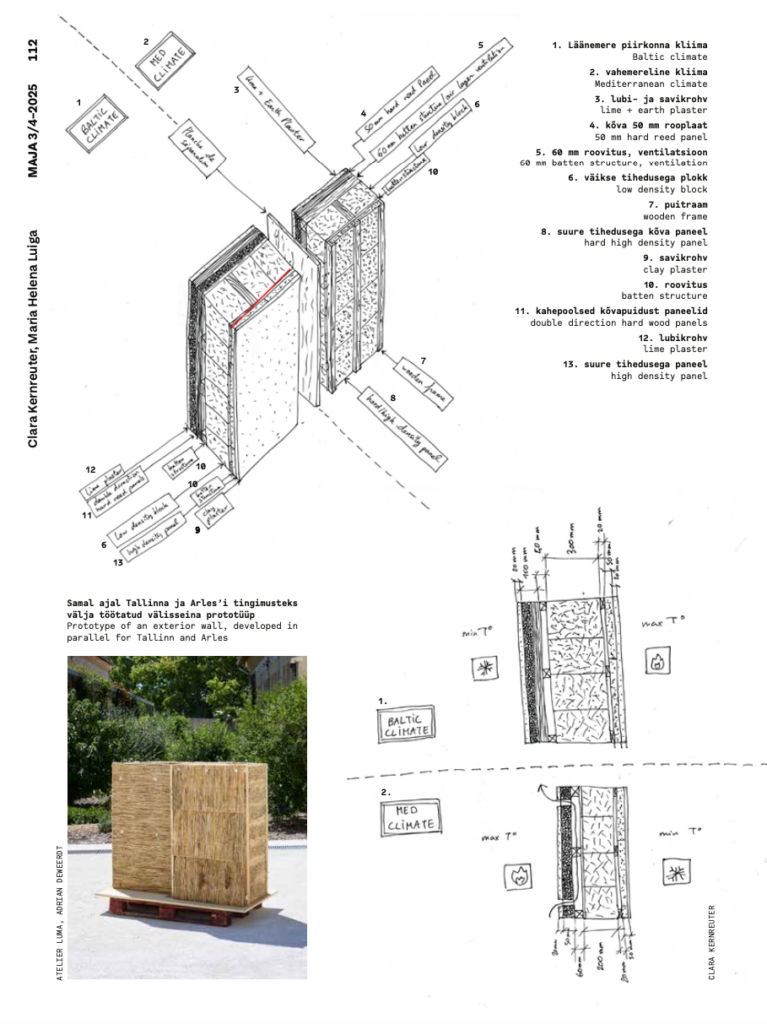

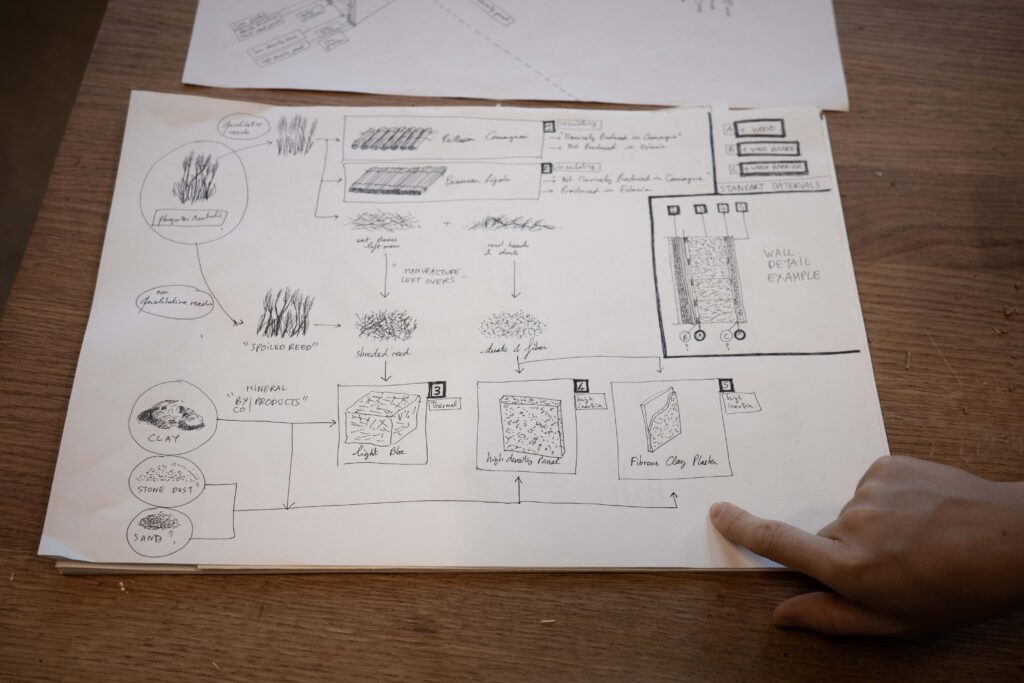

Centred on two abundant local resources, reed (Phragmites australis) and clay, the project investigated their potential as contemporary construction materials, culminating in the design of a speculative external wall section. The research unfolded in parallel across two distinct climate zones, the cold, humid continental climate of Tallinn and the Mediterranean climate of Arles, examining the same resources through localised perspectives, including ecological functions, harvesting logistics, and seasonality, as well as vernacular and contemporary building practices.

Photo: Maria-Helena Luiga

In both bioregions, the common reed forms dense wetland stands (lakes, bogs, coastal zones) and is a key component of the ecosystem: reedbeds provide habitat for many bird species and other fauna, stabilise shorelines, and support nutrient cycling. Material quality varies with site and handling (location and soils, interannual weather, cutting method, sorting, drying, storage). But even though reed is plentiful in both regions, it lacks a substantial output, and supply is poorly aligned with available volumes.

Historically harnessed for thatching and insulation, current uses of reed are narrow: in France, it is mainly used in thin mats for sun-shading and plaster bases; in Estonia, it is used for roof thatching, and a variety of thicker and thinner mats produced for insulation and plastering. Top-grade reed is reserved for hand-crafted roofing, while a range of lower grades is used for wire-woven sub-plaster and insulation mats.

This research and development addressed the mismatch by giving value to surplus and low-grade reed, including production offcuts, to test viability under low-grade input conditions. It progressed from bioregional context and resource analysis to material development and prototyping: reviewing literature and case studies on reed architecture, light-earth construction, and natural building; analysing reed biology, growth environments, and performance; mapping regional stakeholders and reed-based economies to establish cultural, ecological, and economic relevance; and comparing climate zones to define external wall requirements.

The final prototype is a composite external wall section tailored in parallel to Tallinn and Arles, combining the newly developed reed-and-clay materials with existing reed-based products and a timber structure. The assembly integrates light and heavy strategies: one half tuned for cold, damp conditions with wind and freeze–thaw cycles; the other for hot, dry conditions with prolonged sun and seasonal wind.

Building between vision and matter

This work sits between ideology and necessity. When does the bioregional approach to construction cease to be niche and begin to set the norm? Is its future tied to the scalability of production and uninterrupted, homogeneous material flows, or to project-specific use that embraces the seasonality of the resource? How to measure success not only through material efficiency, but also adaptability, resilience, and broader ecological and social impact? Technically, the challenge is to refine material behaviour, fabrication, and assembly without compromising the project’s core principles. Economically, the question is whether reed-based construction can meet local needs while establishing viable value chains for harvesting, processing, and building. Could reed become a considerable regional resource as wetland restoration accelerates across Europe? At this stage, we would like to invite builders, researchers, and material innovators to collaborate with us: to test, share data, and develop pilot projects that connect local reed resources with climate-specific design, helping to imagine, and realise, a truly post-extractive architecture.

Through our work, we came to understand that adopting a bioregional perspective inevitably means confronting contradictions. We cannot simply add value to local resources or waste without questioning the systems that produce them. Which models sustain them? Who truly benefits? And how can vernacular knowledge be mobilised without being folklorised or instrumentalised? Designing within a territory demands time, an attentive ear, and humility, as well as accepting diverse expertise, changing temporalities, and sometimes conflicting values. It proposes a form of chosen sobriety, a slower, situated practice that values connection over extraction. It is a demanding path, but perhaps the only viable one: not to save the planet, but to relearn how to inhabit it with care.

MARIA-HELENA LUIGA is an Estonian architect, lecturer at the Estonian Academy of Arts, and co-founder of kuidas.works.

CLARA KERNREUTER is a French designer whose work bridges ecology and territorial thinking. She is part of the team at Atelier LUMA (LUMA Arles).

HEADER: Atelier Luma meeskond riisipõllul. Foto: Atelier Luma, Joana Luz

PUBLISHED: 3/4-2025 (121-122) with main topic WORK AND FOOD

1 Peter Berg & Raymond F. Dasmann, ‘Reinhabiting California’, The Ecologist 7, no. 10 (1977): 399–401.

2 Robert L. Thayer Jr., LifePlace: Bioregional Thought and Practice (2003).

3 Bernard Picon, L’espace et le temps en Camargue (Actes Sud, 1988)