All new hard infrastructure should be engineered to double as social infrastructure, writes Mattias Malk.

Planning and building a railway might seem like a trivial task on the backdrop of a cluster crisis of climate change, war, rising fascism, skyrocketing cost of living, and social injustice, as well as the (mental) health crises associated with each. Even more so if the railway in question is meant to connect small cities in underpopulated countries at the fringes of Europe. Railways, however, have had a significant historical role in establishing the current urbanised spatial order,1 and they continue to be a sustainable option for transportation. Perhaps even more significantly, infrastructure such as railways consists in dense social, material, aesthetic, and political formations that also reflect and undergird societal expectations for the future.

The tendency to overlook the significance of material infrastructure, such as roads, sewers, power lines, pipelines, and railways, can be etymologically traced. The compound of ‘infra’ and ‘struere’, Latin for ‘below’ and ‘to construct’, has led to infrastructure being described as invisible by definition.2 In social sciences, this view persisted well into the so-called mobility turn of the late 2000s and early 2010s that tried to grapple with the increasingly globalising urban world order. Infrastructure came to be considered most visible when it fails, thus abruptly conveying how vital it is for modern urban life.3 The tension between success and failure, between aspiration and stagnation, has made infrastructure a productive topic for social theory.4

Infrastructure such as railways consists in dense social, material, aesthetic, and political formations that also reflect and undergird societal expectations for the future.

As anthropologist Kregg Hetherington details,5 the putative invisibility of infrastructure is not incidental but inherently connected to uneven geographical development. He says that infrastructure has so far been designed to become invisible, and thus provide stability and a platform for processes of a different order—development, civilisation or simply progress.

However, while infrastructure can give assurance about the future and respond to risks, its definitive feature is not invisibility but the narrative of progress. At a time when future is increasingly seen in dark undertones,6 constructing infrastructure is an act of faith that exhibits anticipation for the future. While planners tend to tout megaprojects such as new rail lines as generative locomotives of progress, these narratives often conceal the projects’ (re-)distributive effects at local scale. It needs to be recognised that decisions on what, how, when, and where to connect provide significant opportunities for shaping cities and the lives of citizens. In the context of globalising urbanity, power and wealth are increasingly concentrated in the hands of those doing the connecting or possessing the knowledge to benefit from it.7 Thus, the task for social scientists is to study both the semiotics and materiality of planning to reveal the relationship of risk and ambition inherent in the promise of infrastructure.

Promise of the century

Rail Baltic (henceforth RB) is a new international rail corridor between Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland that is currently under construction. It aims to improve the connection between the Baltic states and core EU countries with a fully electrified railway, setting in stone a geopolitical shift that has been underway since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Originally set to become operational in 2026, the project currently faces a delay of at least four years. Even by 2030, the system may be only partly functional.8 RB is part of a key EU policy that addresses spatial inequality and promotes territorial cohesion through the development of the Trans-European Transport Network. While developing railways is a particular focus for the EU due to rail travel being a more sustainable alternative to air and road travel, it is also a conscious attempt to mitigate the 19th-century nation-state origins of rail infrastructure.9

Redrawing of colonial lines is one reason why RB can be and is promoted locally as the ‘project of the century’.10 However, beyond its geopolitical function, RB is also extraordinary for its cost, complexity, project duration, and its potential to significantly impact spatial planning in the region for decades to come.11 Early on, RB began to be described as a ‘tool for development’.12 Its macroeconomic promise has been echoed in a series of cost-benefit analyses, which have in turn been contested by lobbyists and quarrelled over in countless opinion articles. RB’s hegemonic imaginary as a source of development and territorial cohesion is also evident in a series of promotional images, maps, calculations, and media stories generated around it. However, despite the project being in the public eye for over a decade, there is little societal consensus about it. Many do not understand whether or why RB is being built. Others see that its resources would be more wisely spent elsewhere—on issues more relevant to their everyday lives than a promised connection to Berlin. While this highlights key communicative shortcomings of RB managers, it also reflects more generally the inherent (re-)distributive effects of new mobility infrastructure. The question then becomes, if RB is a tool, then who wields it, and who is effectively moulded by it?

While parts of RB are under construction, others are yet to be planned. Some indications of its spatial strategies, intent, and potential impact can be gathered from in-depth case studies and expert interviews. Development of the station area in Tallinn13 and implementation of RB in Pärnu14 have already highlighted serious shortcomings in the planning process. In short, democratic deficit, strategic misrepresentation, and overall opacity are commonplace and reveal the region’s relative lack of experience in building megaprojects.

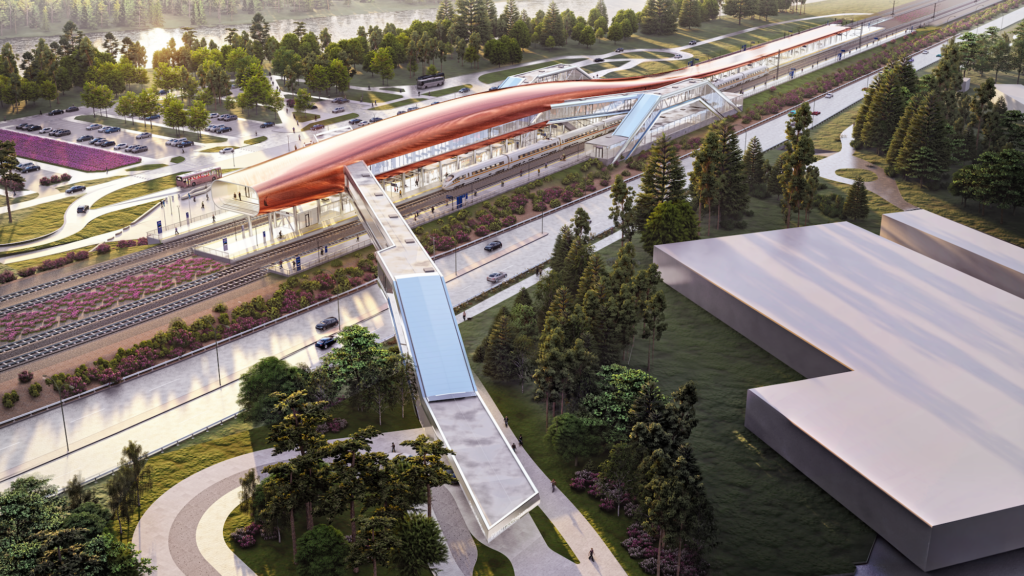

The architecture competition for the Tallinn terminal involved a series of questionable decisions that add up to the greatest missed opportunity of all time in the spatial planning of Tallinn. First, rebuilding the current central station (Balti Jaam) and navigating extra rails through the city were considered too complex. Next, local architecture office 3+1 Architects was strong-armed out of the project using an amendable legal catch. Ultimately, a highly conflicted second architecture competition produced a starchitect design that, while visually stunning in renders, is costly, difficult to build, and comes across as generic brand architecture. Instead of a heterotopic multimodal node embedded in the heart of the capital, Tallinn will now end up with a peripheral station that has been described as an architectural equivalent of displaying your wealth with a Birkin bag.15

Tallinn will now end up with a peripheral station that has been described as an architectural equivalent of displaying your wealth with a Birkin bag.

The divergence between promises and reality is further evident in how RB has been planned in secondary urban areas such as Pärnu, Estonia. Although intermediate cities, the places between capitals, may greatly benefit from new rail projects, actual outcomes depend on a clear municipal strategy. Furthermore, specific outcomes are liable to the influence of existing spatial elites and urban hierarchies. The railway itself is not enough to foster stable development in intermediate cities. Instead, urban development and rail development need to be mutually supportive. To achieve this, it is vital to consider the needs of the local populace and involve them in decision-making. Where municipal strategies and budgets fall short, uneven geographic development may instead intensify. Without due integration into the urban fabric, the train tends to move what is already on the move. In the case of Pärnu, this would mean intensification of the already ongoing workforce drain to Tallinn and continued decline of regional economic significance.

It is clearly imperative to learn from RB’s planning so that there could be more socially responsible outcomes in the future. Beyond the two examples just mentioned, RB provides many vital lessons about the complexity of planning an international mobility corridor in partnership with other nations and in a larger context of EU policies, including the new geopolitical lines being drawn between east and west. In a sense, RB puts the whole idea of Baltic states as a region to the test. Can we cooperate towards a cohesive network of economic centres—something like the Randstad in the Netherlands—or are we destined to provincial competition with each other?

Can we cooperate towards a cohesive network of economic centres—something like the Randstad in the Netherlands—or are we destined to provincial competition with each other?

Are ya winning, son?

What would success look like in the case of planning RB? Determining success or failure in planning is not straightforward. Planning, like democracy, is laden with ideological undercurrents and has different meanings in different contexts. In general terms, planning can be defined as a future-oriented process through which control over existing circumstances is sought.16 One possible measure of success is public opinion. For decision-makers, especially politically elected officials, it is vital to know how their efforts are received. However, public reaction can be vague, unpredictable, and subject to change, especially in the case of more radical planning aims. For a researcher, it might be more valid to gauge success by comparing the planning process and its results with the planners’ original intent.

When assessed based on the so-called Iron Triangle of delivery concerns—i.e., whether a project falls within the constraints of time, budget, and scope—RB can be summarily judged a failure. However, being ‘over budget, over time, over and over again’17 tends to be the rule rather than exception with most megaprojects. Due to the duration and complexity of planning and building RB, it is vulnerable to externalities as well as internal challenges. It could also be argued that a project of such economic, political, social, and ecological significance should not be measured by stiff project management criteria alone. Instead, it is crucial to consider the aims that RB has specified for itself.18

In its own words, RB aims to be ‘environmentally friendly’, ‘safe’, and ‘modern’. Environmental targets are to be achieved by avoiding local emissions, utilising novel technologies, and mitigating any impacts on protected areas. Safety is sought through traffic management systems, elevated crossings, and station design. The third general aim—to be modern—aligns most clearly with the overall narrative of progress and development that is associated with infrastructure planning. This consists in promising to employ novel materials and technologies as well as describing the kinds of multimodal cargo and passenger terminals to be built. However, aims that would touch upon overall spatial strategy are conspicuously absent. It remains unclear how RB plans to fit into the existing built environment and what impact it is going to have on the future everyday lives of citizens.

Without due integration into the urban fabric, the train tends to move what is already on the move.

Perhaps RB should add a fourth pillar to its aims—an aim to be ‘local’. In addition to promising quick transfers to Pärnu, Riga, and Berlin, RB could prioritise improving the overall spatial quality of wherever its infrastructure is physically situated. Sociologist Eric Klinenberg has described public places built in this manner as ‘palaces for the people’.19 While Klinenberg’s focus is on social infrastructure such as libraries, parks, sporting grounds, and other physical spaces that shape the way in which citizens interact with each other, he also notes that conventional hard infrastructure can be engineered to double as social infrastructure. Examples of this are increasingly plentiful around the world.

For instance, CopenHill by BIG has transformed a waste-to-energy plant from a NIMBY20 eyesore to a popular skiing hill and climbing wall. Munich’s iconic surfing community is made possible by a standing wave that forms when the fast-flowing river Eisbach passes over a bump installed in the riverbed. Even though the closest seacoast is hundreds of kilometres away, neoprene-clad surfers are commonplace in the city. In Tallinn, the roof of the newly built cruise terminal doubles as a scenic promenade with a host of free activities (although it can be called ‘public’ only with some caveats).21 Elsewhere, simply opening up the railway service road to cyclists has been a common simple, efficient, and low-cost strategy to maximise potential users.

Photo: Mattias Malk

Supplementing the narrow focus on technical parameters, spatial strategy should be a vital measure of success in planning infrastructure. Given all the megaproject planning that the Baltic countries will need to undertake in the current cluster crisis, this may be the most important lesson to draw from RB. In short, all new hard infrastructure should be engineered to double as social infrastructure.

As a society, we should place much higher expectations on infrastructure projects. Rather than being an invisible underlay to other action, infrastructure is crucial in determining future ways of living together. Investments in high-quality hard and soft infrastructure that is macroeconomically ambitious and equitable, as well as locally and socially generative spatial interventions are of key importance. A rail project implemented in such a way might then be perceived as a success even by someone who never takes the train.

MATTIAS MALK is an urbanist, PhD student and lecturer who enjoys excellent infrastructure and generously planned streets.

HEADER photo by Mattias Malk

PUBLISHED: MAJA 3-2024 (117) with main topic INFRASTRUCTURE

1 Wolfgang Schievelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century (University of California Press, 1977).

2 Susan Leigh Star, ‘The Ethnography of Infrastructure’, American Behavioral Scientist 43, no. 3 (1999): pp. 380–82.

3 Stephen Graham, Disrupted Cities: When Infrastructure Fails (Routledge, 2010).

4 Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel, The Promise of Infrastructure (Duke University Press, 2018).

5 Kregg Hetherington, ‘Surveying the future perfect: Anthropology, development and the promise of infrastructure’, in Infrastructures and Social Complexity, eds. P. Harvey, C. Jensen, and A.Morita (New York: Routledge, 2016).

6 Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, After the Future (AK Press, 2011).

7 Bent Flyvbjerg, Nils Bruzelius, and Werner Rothengatter, Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

8 ‘Baltic audit offices: Rail Baltica looking at €19 billion deficit’, ERR, 12 June 2024.

9 Roger Vickerman, ‘High-speed rail and regional development: the case of intermediate stations’, The Journal of Transport Geography 42 (2015): pp. 157–165.

10 ‘Rail Baltica—Project of the Century’, RB Rail AS, https://www.railbaltica.org/about-rail-baltica/.

11 Estonian Cooperation Assembly, Estonian Human Development Report 2019/2020:

Spatial Choices for an Urbanised Society (Tallinn: SA Eesti Koostöö Kogu, 2020).

12 Pavel Telicka, ‘Annual Activity Report, Priority Project No 27, Rail Baltica’ (2006).

13 Mattias Malk, ‘Delayed arrival: planning, competition and conflict in the Rail Baltic terminal project in Tallinn, Estonia’, European Planning Studies 31, no. 10 (2022): pp. 2216–2234.

14 Mattias Malk, ‘When the first train departs… Understanding the work of imaginaries in infrastructural renewal in Pärnu, Estonia’, The Journal of Transport Geography 117, no. 3–4 (2024): 103873.

15 Merle Karro-Kalberg, ‘Ülemiste RB terminal nagu Birkini käekott’ [‘Ülemiste Terminal—a

Birkin Bag’], Sirp, 19 December 2019.

16 Tim Knudsen, ‘Success in Planning’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 12, no. 4 (1988): pp. 550–565.

17 Bent Flyvbjerg, ‘What You Should Know About Megaprojects and Why: An Overview’, Project

Management Journal 45, no. 2 (2014): pp. 6–19.

18 ‘Rail Baltica—Project of the Century’, RB Rail AS, https://www.railbaltica.org/about-rail-baltica/.

19 Eric Klinenberg, Palaces for the People (Crown Publishers, 2019).

20 Acronym for ‘not in my backyard’.

21 Mattias Malk, ‘Peaegu kilomeeter peaaegu avalikku ruumi’ [‘Nearly a Kilometre of Nearly Public Space’], Sirp, 20 August 2021.