OUTSET

From Cornerstone to Worktop and Back Again

Laura Linsi, Maria Helena Luiga, Roland Reemaa

CASE STUDY

15 Clerkenwell Close

Groupwork

CASE STUDY

62 Rue Oberkampf

Barrault Pressacco

CASE STUDY

Plan-les-Ouates

Atelier Arciplein, Perraudin Architects

IN PRACTICE

Moss Doesn’t Grow…

Helena Keskküla

ESSAY

Houses of Time. Carbonate rock in Estonian buildings

Helle Perens

PROJECTS

Limestone in 21st-century Estonian Buildings

Johan Tali, Merle Karro-Kalberg, Hanna Karits, Priit Õunapuu, Siiri Vallner

EDUCATION

Working Stone

Juliet Haysom, Thomas Randall-Page

ESSAY

On Stone’s Shoulders

Carl-Dag Lige

ESSAY

Linnahall is Sedimenting

Madli Kaljuste

ESSAY

Sedimentary Flows and Creative Geologies

Galaad Van Daele

IN PRACTICE

Sisyphos and Portland Stone

Amaya Hernandez

REVISIT

Is Don Quijote at It Again?

Rein Einasto, Hubert Matve

STONE

Much can be inferred from what has been written in stone. Limestone, for instance, contains data on climate change. According to geologist Rein Einasto (p. 104), geologists can use limestone to infer that we are currently going through the greatest transition in the history of life, one in which our ways of thinking and living must change radically in order for us to survive as a species. Thinking through stone opens up a perspective that extends over hundreds of millions of years, in which geological materials are not mere static resources to be appropriated, but participants in terrestrial cycles. Architect Galaad Van Daele, who sees in this an opportunity of collaboration between mineral, organic and cultural life, writes: ‘We architects need a geological literacy.’ (p. 86)

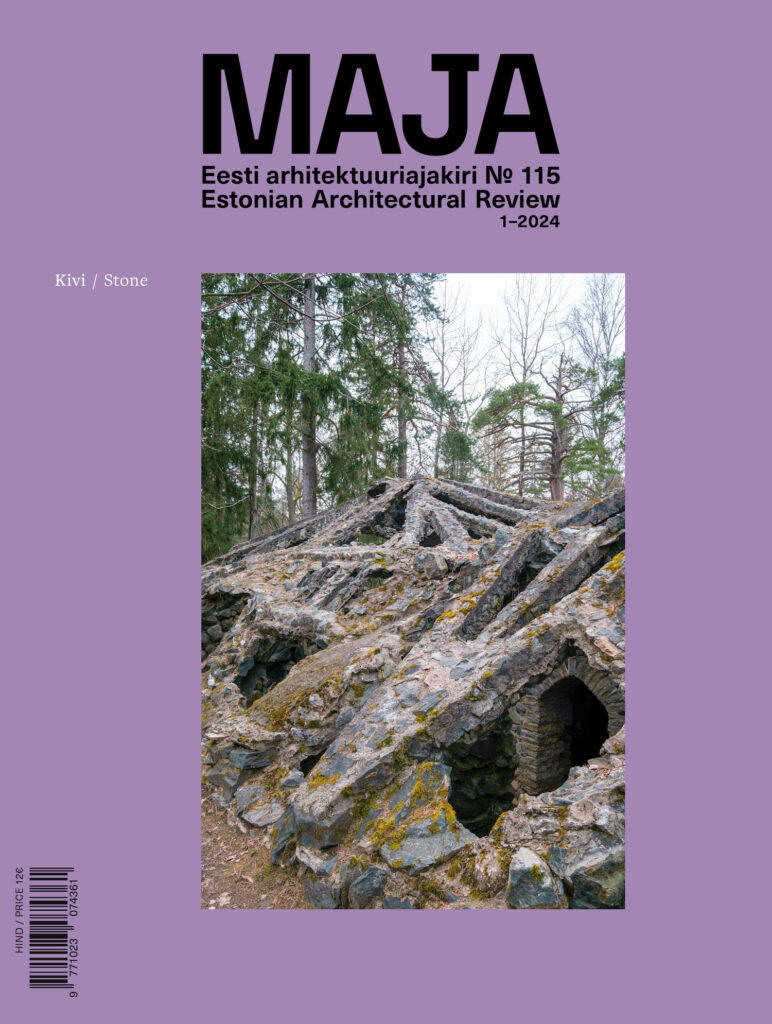

Too expensive, too labour-intensive, too time-consuming. Building with stone seems either outdated or strictly a luxury thing, and yet, a new Stone Age is looming in West Europe—building stone’s wide availability and low levels of embodied carbon make it suitable for use in load-bearing structures of social housing, as well as experimenting with wholly new kinds of structures (p. 6). The limestone deposits of Estonia likewise contain some layers that are marble-strength and weather-proof. Could our local limestone become a widely used building material once again?

To be sure, extracting natural stone has a footprint, but after extraction, it does not require much processing to be ready for use in construction. This sets stone apart from energy-intensive concrete, clay brick and steel production. Geologist Helle Perens emphasises that instead of worrying about the environmental impact of quarrying building stone, we should worry that there are plans for the near future to extract senseless amounts of it, including very high-quality stone, only to crush it into aggregate (p. 34). We tend to be careless with stone—both with the stone still in the ground and stone in the walls of disused buildings. Architect Madli Kaljuste takes a look at one of such buildings that hides traces of 400-million-years-old life in its walls (p. 78). Thinking through stone opens up a fresh perspective on construction culture (and the lack thereof), availability of local building materials and their untapped (economic) potential, and, ultimately, on building truly long-lasting buildings.

Editor-in-chief Laura Linsi

March, 2024