THE RECONSTRUCTION OF NARVA CASTLE CONVENT HOUSE. STAGE 1

Architecture and interior architecture: Kalle Vellevoog, Tiiu Truus (architecture office JVR, Stuudio Truus)

Project team: Andrus Andrejev, Martin Prommik, Lidia Zarudnaya, Annika Liivo (architecture office JVR, Stuudio Truus)

Engineering: EstKONSULT

Exposition: Arhitekt11, Identity

Commissioned by: Narva Muuseum

Project manager of the contracting body: Jüri Moor

Construction by: Scandec Ehitus

Net area: 4450m2

Competition: 2015

Project: 2015-2018

Constructed: 2018-2020

Rather than exhibiting objects and asking questions, the contemporary museum has become a place for experiences requiring submission to the logic of storytelling. Triin Ojari considers how the reconstructed Narva Castle relates to history and providing experiences.

Four medieval castles in Estonia have been taken into use as museums—Haapsalu, Kuressaare, Narva and Rakvere—and in addition, there are museums in Põltsamaa Castle and Paide Rampart Tower built in the former order castles and also a modern visitor centre in the Vastseliina Castle ruins. As a legacy of the decades of work by Soviet restoration enthusiasts, most castle museums feature the stylistics of the restoration principles of the time and illustrate how history was constructed by literally rebuilding and shaping it. During the Soviet period, the political context of the renovation of bastions recounting the history of Estonia’s subjugation and also the restorers’ motivation were obviously very different than today. Heritage protection and conservation in a way became acts of identity formation, as in the general defensive attitude geared by the fear of sovietisation, historic buildings were considered valuable per se with their unique qualities opposing to the waves of modernisation and demolition that were bulldozing the country along the official centralised initiatives. The post-war obliteration of the city of Narva is one of its most tragic examples leaving the Hermann Castle among the few remaining buildings—and for a long time merely as overgrown ruins.

Today, however, we are considerably better informed about the post-colonial cultural situation and the respective reinterpretation of history, we accept the subjectivity of history and the plurality of viewpoints, including the ones told from the position of the repressed and the so-called others. On the one hand, the Estonian order and episcopal castles as belligerent symbols of power dominating the landscape even when in ruins represent violence and foreign power, telling the story of the winners while also providing a premise for discussions on the meaningfulness of warfare and political oppositions as well as the transience of power. On the social level, we can also talk about the curious cohabitation model of people from various social classes with their daily life permeated by military and religious rituals—thus, castles as signifiers are a rich source of abundant stories. Do the historic castle walls also dictate the way how to exhibit and talk about history within them?

When looking at castles as spatial entities, they have all suffered great damage in wars, constantly changed their shape and components, and despite their original menacing monumentality, they have all to a greater or lesser degree become ruins or objects where the lack of matter is as telling as the visible substance. Everything that does not exist can be imagined, and it is the firing of this imagination that has become the main function of contemporary castle museums. Instead of discussions and enquiries, they have combined history and entertainment, truth and fiction with playful ease, as the entire space with all the passages and recesses, cells, chapter houses or towers seems to be perfect for the ‘production of history’ with a performative and dramatic structure1. It seems that reproducing the medieval or early modern era in a thrillingly experiential form has levelled out all other possibilities to perceive the past while the contemporary world of digital means has only added fuel to the attempt to create new realities. It is not that the interactive hands-on method of transmitting information is in any way more superficial than the text-based ones, quite the contrary, a finely tuned experience will be etched on people’s muscle memory and the historic environment of castles certainly has the power to trigger their imagination, the problem here is that there seems to be no problem and usually an illustrative visual language imitating the fictional reality is selected that leaves no room for ambivalence or critical revision and tends to present history in a ready-made form. If the cultural function seems to be the only possible use for Estonian strongholds (true, Toompea Castle, housing the Estonian Parliament is unprecedentedly still the bastion of the legislative state power), they should perhaps also leave more room for various ways of presentation.

The Comebacks of Narva Hermann Castle

Now also on the bandwagon of rejuvenation, Narva Castle was originally built in the 12-13th century and later recurrently improved according to the changing art of warfare. With its height of 50 metres providing good views of the enemy line across the river, the Tall Hermann Tower is among the mightiest ones in the Baltic states, although the current form was given to it only in the restoration begun in 1968 after the tower and the convent house had been largely destroyed during the war. In the course of the reconstruction, they made bold use of concrete, added new staircases and floors while the new gabled spire with a wooden external walkway and similar passages on the walls conveyed the traditional image of a powerful medieval border castle. Pursuant to the non-commercial Soviet cultural policy, the museum of the history of Narva with abundant exhibition spaces for permanent and temporary expositions was opened here in 1986 (the museum is still known for its spaciousness accommodating a number of competing temporary exhibitions during the annual museum festival).

The historical expositions featuring showcases crammed with objects and information have long disappeared from the contemporary museum scene that now largely consists of visitor, family and activity centres. In view of the massiveness of the castle, it is logical that the spaces deserve a better and more versatile use attracting further visitor flows and economic activity. Now midway through the process, the renovation of Narva Castle was begun in 2015 together with Haapsalu Castle, with the latter completed with utmost deference (architectural design by KAOS Architects) a year earlier in 2019. Attracting visitors with the promise of ‘a medieval adventure’, Rakvere Order Castle was the first medieval theme park to be opened in 2003 bringing effortlessly together the life of fortification and fornication, swordsmen and healers with new packages continuously added to the list. The role of Saaremaa Museum in Kuressaare Castle as a classic local history museum has held firm for more than half a century without the magic wand of a theme park, instead, the energy has been channelled to the restoration of the fortifications surrounding the best-preserved castle in Estonia in their original glory. Similarly to Haapsalu, also Narva received European funding to launch the development of the castle as a tourist attraction including the renewal of the logistics and functions of the entire complex, new spatial solutions for the castle together with updated expositions as well as possible new buildings. Typically of such projects, it requires a financially beneficial investment warranted by future activities, that is, going for a safe bet with a visitor and conference centre to attract the tourism market with the unique building as a strong selling point.

The Castle as a Playing Field

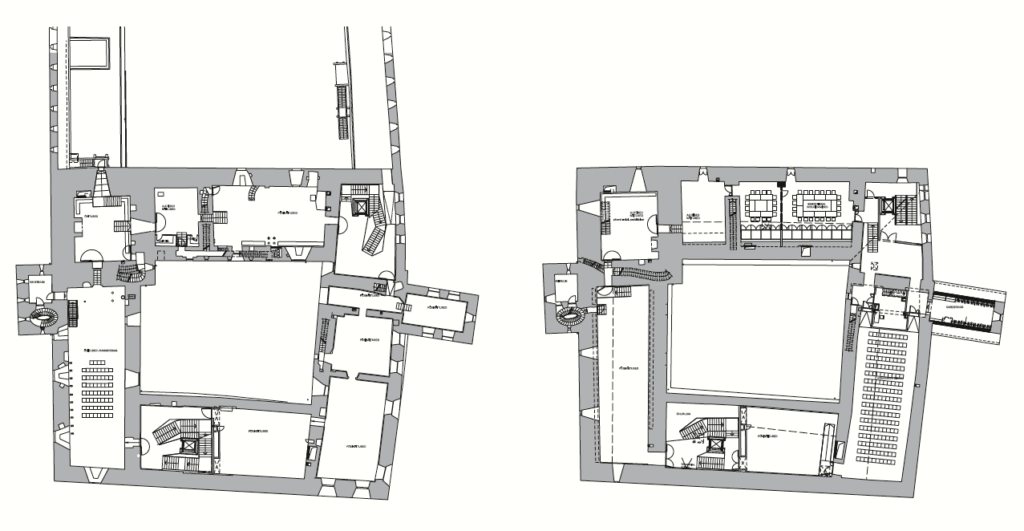

The winners of the 2015 architecture competition JVR (Kalle Vellevoog, Tiiu Truus, Lidia Zarudnaya, Martin Prommik) now revealed the first stage of their project. The convent house has been given (at this point only partially) new pathways, connections, technical solutions and also the exposition. The Western Courtyard (a large outer ward where the entire town could be accommodated in the 14th century, if necessary), paved passages, a bridge over the moat and a new staircase connecting the castle on the steep slope with Joaoru Promenade below will be waiting for their completion in the next stage. However, the construction of the outdoor areas is highly important as in the contemporary castle museum concept, the indoor and outdoor activities are closely interconnected and the active open-air facilities are used either as a medieval theme park as in Rakvere or as a festival venue as in Kuressaare and Haapsalu.

In the past 15 years, the Western Courtyard of Narva Castle has hosted re-enactments of historic battles with military history clubs playing out the combats of the Great Northern War. For a while already, there has also been a handicraft workshop area in the Northern Courtyard connected to the convent house with costumed characters earnestly playing their roles in the tavern, smithery or workshop in the spirit of a proper theme park. There is no manure, shouting or livestock mingling with people, though, and the image of the Middle Ages is conveyed in a restrained and civilised manner. The new solution leads visitors to the castle through the souvenir shop and the craftsmen’s courtyard followed by the exposition halls mixing various eras—accustomed to the rapidly changing environments in the virtual reality, our consciousness is now already used to allowing itself to be briefly charmed by a deluge of images set in a physical space (that’s why we’ve come here in the first place!) until another game or page brushes them aside. We want to consume various environments as quickly and compactly as possible and Narva provides perfect opportunities for it. Done with the Middle Ages, seen the Great Northern War, let’s have lunch now!

The longstanding tandem team of Vellevoog and Truus bring their own distinctive layer into the historic environment. Their architectural handwriting is clear and simple with the new doors, windows, stairs, balustrades and other elements markedly distinguishable from the old in material (metal, glass, concrete), form and colour—all new additions are minimalistic and black. With clever lighting, it does not require much else as the building alone in all its historic layers is thrilling enough. The aesthetically laconic and unambiguously contemporary details act as a dignified background rather than soloists.

The main changes include a new main entrance through the rectangular inner courtyard of the convent house that has been recently cleaned of all excessive items and complemented with a laconic wide concrete steps for various events while the building has been given completely new inner logistics. Two new vestibules with lifts were established by demolishing and expanding the staircases from the Soviet times, and, in terms of engineering, the stairs with their seemingly floating design form a separate attraction—in the medieval space, references to the stairwell mazes on Escher’s graphic works seem quite appropriate. The new doors and windows are placed over the original openings pursuant to the reversibility principle of all new additions currently followed in heritage protection, and actually this was the only way to achieve the necessary width for the escape routes. By taking into use the eastern wing that so far had been closed for visitors, the building around the inner courtyard can now be circumnavigated on the second-floor level while the construction of the conference centre on the third floor will wait for its turn.

As a visitor I’m happy that all the rooms have not been filled to the brim allowing us to go about the building admiring the vaults in some rooms, touching the curious formations protruding from the wall or just letting one’s eyes wander in other spaces. Experiences should not be deliberately produced, they should be allowed to emerge. The maze-like castles are inherently ideal places for wandering, they were never meant for seamless passing through, instead, the function of the various segmented security zones was to provide safety and escape from constant danger. The architects have certainly contributed to the new logical trajectories in the museum, however, the sense of getting lost never left me as a visitor and this is only commendable.

An Exhibition Staging the History

Without dwelling any further on the exposition (Arhitekt 11 and concept design agency Identity) based not so much on objects as on special solutions and new items, it may be said that the above-mentioned key changes evident in the museum scene are also featured here: instead of showing things, it has become a place for experience with the mandatory requirements of narrativity and submission to the logic of story-telling. Digital technology in both presenting and interpreting culture is here to stay, so the only question is how to use it—aren’t the gigantic faces dominating the Hall of Confrontation with various symbolic portraits of the opposing sides (including the Estonian first president Konstantin Päts and Lenin, the leader of Communist Russia) projected to stare at each other and the incomprehensible set of sounds in the background a tad too simplistic for presenting history? And even if it is impossible to do without dummies dressed as warriors but seated in tranquil positions, is it still mandatory to have a blood-spattered mannequin victim lying in the corner without any explanation? A month after the opening, there are still no labels on the exhibits and the museum guides in the halls are trying to stand in for the audio guides real-time—one could easily take this kind of a personal approach as part of the overall concept! As befitting the military background of the building, the exposition focuses on the history of wars, violence, weaponry, uniforms and an armour (a modern version) as well as on the transformations of the castle while there is not a single word about the residents, superiors or subordinates. Wars provide the drama, no doubt, and instead of the multidimensional content, the focus here is on curating emotions and the visual fireworks. Then again, the exhibits are not too numerous and, in some rooms, one might feel the need for a total space to immerse the visitors in for a moment. In the renewed part of the castle as a whole, the space and the objects within remain disconnected and the above-mentioned experiential approach tends to be fragmented and scattered. Appetite is whetted but not satisfied.

Museums are places where history is not defined but instead produced in time and space. Narva Castle, first owned by the Danes, then by Germans, Swedes, Russians and in the past century also Estonians while located in the middle of a Russian-speaking city, is a culturally thrilling challenge—and the pertinence of the statement was also proven by the political tension between the museum foundation and the city, let us call it a difference of visions. The old castle epitomises the drama and loss of history as well as its reproduction through a physical space, theatrical activities and the image created by digital means, and there are actually numerous stories.

TRIIN OJARI is an architecture historian and the Director of the Estonian Museum of Architecture.

PHOTOS: Kalle Veesaar

PUBLISHED: Maja 101-102 (summer-fall 2020) Interior Design

1 Saaremaa Art Biennales curated by Peeter Linnap and Eve Kiiler in Kuressaare Castle in 1995 and 1997 serve as a good counterexample of bringing together medieval spaces and contemporary art problematising history.