KAMARI WAKEPARK BUILDING

Location: Lake Kamari, Põltsamaa

Architecture and interior architecture: Peeter Pere, Eva Kedelauk / Peeter Pere Arhitektid

Structural Project: Valgur Projekt

Construction: Embach Ehitus

Commissioned by: Embach Ehitus

Total area: 406,1m2

Project: 2020

Completed: 2020

The nominee of The Cultural Endowment of Estonia in architecture 2020.

A building may use its own words to speak its own truth, despite the utterings of the system it belongs to. As such, a building may also be quite quiet, in a pleasant way. Calm and unintrusive.

What the building does not have

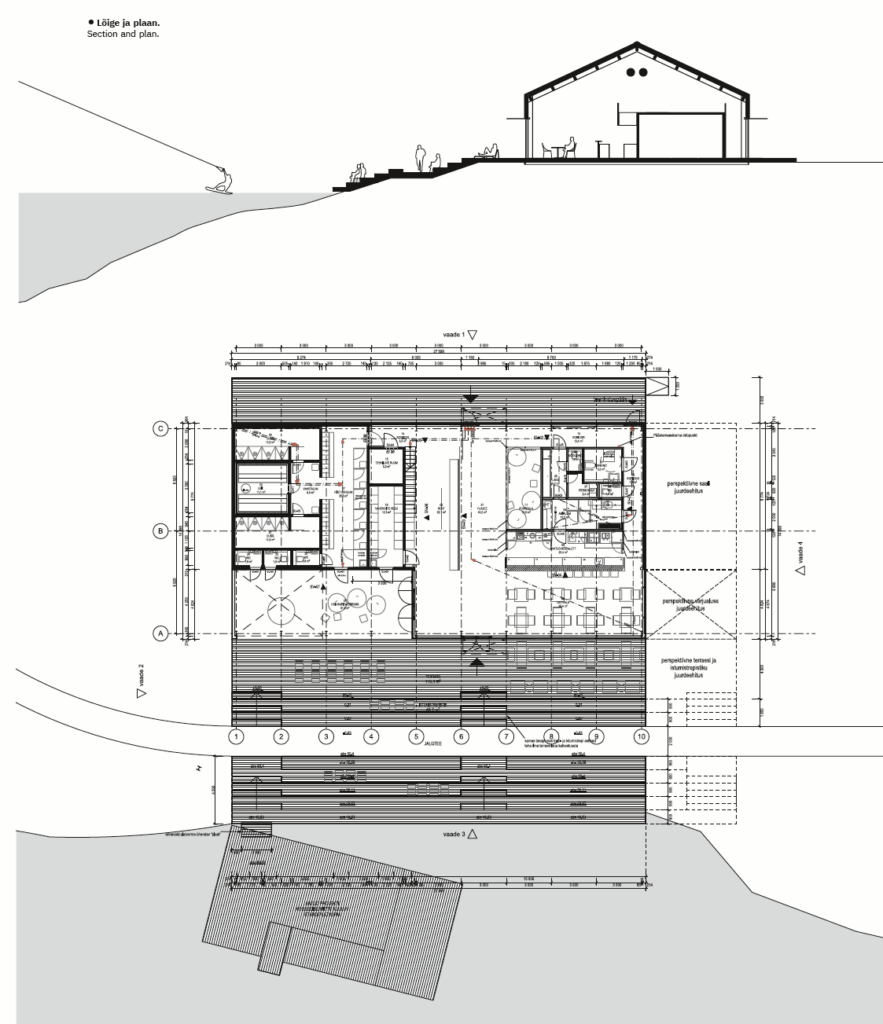

The Kamari Wakepark Building is located by Lake Kamari in Põltsamaa. The cable lines and concrete elements on the lake are all set to give visitors a ride; the washing and rental services as well as the main lobby of the wakeboarding centre are situated on the north-eastern shore of the lake. Rolled metal sheets diffusely reflecting the surrounding weather cover the building, defined by clear lines. The metal sheet cover is light and makes the building seem industrial and uncomplicated.

The inconspicuousness of an industrial building becomes conspicuous by a stunningly chaste build, rendering the silhouette of the house graphical.

The simplicity of the architectural form has a soothing effect. In the small-town context of Põltsamaa, a solution as serene as that entails defiance. Perhaps it is in small towns in particular that we encounter a stronger urge to empower place identity through spatial solutions. At the same time, a glance into the past might not express that which is currently essential. The Kamari Wakepark Building has simple curvature and positions itself in the now, perhaps even in the most present of moments, without binding itself to the town of Põltsamaa through any spatial symbolism.

Is that a loss for the town? Composing urban centres, (small) town squares, involves an identical spatial dualism—on the one hand, the aim is to create a place for present-moment time, on the other, to impress upon individuality and find a distinct image, which is precisely why looking to the past becomes almost a knee jerk reaction. It is an intent to capture place identity using spatial means. Central squares are often the places where a statement about the entire town or community using spatial vocabulary would be appropriate but using symbols from the past is an all too slippery slope to caricature, inhibiting the potential of the place to change.

In that light, the serenity and unpretentiousness of Kamari Wakepark is a bold conjecture. It upholds no need to be saturated by any motifs. It is made simple; it is made for the now. It is not a so-called copy of a bygone house. It is a good example of how to inset unexpected freshness by mere presence in time. As such, the building has been left with the freedom to find its own identity—it can engage with the place on its own terms, without any previous attunement to architectural symbolism. Something entirely different has been spatialised instead—things attached to a specific activity, that is, wakeboarding, not Põltsamaa.

Perhaps it was easier for the Kamari wakeboard centre to not become attached to the face of the town due to its location away from the heart of Põltsamaa. That type of solution is supported by the supposition that the building has probably never been under any significant pressure to symbolise anything, because it is situated at a considerable distance from the centre, toward the south, in the periphery. It rather connects to the seemingly peripheral industrial architecture, intentionally inconspicuous like those large industrial hangars. It is easy to pass by one of those.

Sheet metal as the material of choice comes across not only as light and industrial but tenaciously opposing the wood. Establishing landmark buildings increasingly out of wood has been a benign tendency in the construction scenery. It is as if a general Zeitgeist is putting emphasis on environmentally friendly building materials being used. Choice of material is undoubtedly an important aspect of embodiment for the physical manifestation of a building—in some cases material may be the distinguishing perceptive agent even more so than form.

There is no external cue that any wood has been used on the inside of this building, which means it is not a pro-wood business card attempt. It also reduces the possible identities down by one and leaves the building in an unpretentious state. That makes the wood used in the outdoor space around the building stand out even more—there are long, large-scale wooden terrace stairs for sitting and hanging out, creating a warm contrast to the metal sheet house.

What the building does have

The terms of reference are remarkably simple—anyone looking to engage in wakeboarding will need a building with storage and washing function. Monofunctionality can be an expansive facet for a building; for creating a spatialised sequence of movement.

The habitual inconspicuousness of an industrial building is lessened by its beautifully clean build, rendering the outline of the house graphical. Nowhere does the metal sheet pour over, even the angle between the wall and the roof is joined without covering over each other. The lines of the metal sheet panels run straight and are laid out on the facade, there are no snow stoppers on the roof—the form is open, and the accentuated roof ridge attains an ornamental dimension.

The ingenuousness imbued in the architectural space of the wakeboarding centre is not minimalism, however. It is a type of simplicity that allows entering and passing through the rooms and changing things around, pronouncing an aspect of use and usability. The sterility of minimalism might leave a trail of feeling that an addition here or there would disturb or ruin something entirely. Minimalism entails a certain kind of aggression in the form of inaccessibility, untouchability. But a human being in a space always adds something.

Adding a rest area for the employees is under work during the quiet winter season. A prerequisite for that was turning the front of the technical room on the second floor into an office space. ‘Office area’ is an open space with a view to the lively first floor. The stairway leading to the technical room and employee area is narrow and with a steep elevation angle, with transparent steps made from metal grid and fine cable for guardrails. The non-standard appearance is reminiscent of level connections in industrial landscapes where there is a plenitude of various solutions to stairways-ascensions. It is a transparent landscape, a forbidden one with direct access, with foreign standards. With solutions which upon closing seem to equally respond to matters of cohesion, without extensions or concessions. Thus, more similar to the one-dimensional metal spiral staircases on the silo tanks at Imavere junction rather than the stair-space featuring on the exterior wall of Fotografiska.

The internals of the building unfold into the face of the building. In hierarchical terms, we might say that its identity is built bottom-up—there is no trace of a broader interest, from the beginning the aim is to make something small and of one’s own. An approach like this, combined with non-use of symbols or motifs, grants a certain freedom. The building may use its own words to speak its own truth, despite the utterings of the system it belongs to. As such, the building may also be quite quiet, in a pleasant way. Calm and unintrusive.

Possibilities: general and local

The singularity of the Kamari Wakeboard Building nonetheless comes with a slack for possible future scenarios.

Although the wakeboard centre has a distinct purpose, it was nonetheless built with possibilities for further use. The first slack is apparent in the ’homeothermic’ nature of an otherwise completely seasonal building. The house from one season is prepared, vacant and warm for the three other seasons to come.

To what degree and by which means can the identity of a building be shaped, anyway? How might the foundation be laid for a structure that enables uninhibited evolution and emergence of an identity? In the given context, the starting point could be the seasonal nature of the planned activity. We might say that the wakeboard centre does not represent Põltsamaa as much as it represents its own function, which is extremely seasonal—wakeboarding is a sport of the summer period only.

It would seem then, that as a functional building it would need to be heterothermic, so to speak, equipped with a minimum heating solution while prepared for seasonal use. But why is it heated year-round; why is it not a one-season structure? Lack of seasonality in the architecture actually grasps attention on a broader scale. Modern summerhouses are no longer designed for spending the summer there only, either. They have become more like getaway destinations, quiet oases outside the city meant for visiting regardless of weather or the time of year. Natural cycles are no longer the defining factors behind the designs of houses or lifestyles. Presumedly, emergence of perennial added purposes for the Kamari wakeboard park is only a matter of time.

The wakeboard centre at Kamari is a conscious destination, not a place you happen to find yourself in. Peripherality is a good thing. The artificial lake has become visible, a reason to visit the place has been created. There are plenty of other places across Estonia that have been turned into designated destinations due to implementation of specific activities there. A certain distribution is happening in contrast to the compression into cities. We should strive more toward this type of diffusion because it has an integrative effect on the Estonian state. This way, it would be possible to go to a specific location, and not some place where everything you might need is supplied. To some extent, this type of particularity has been introduced in Estonia, for instance, with spas. Peripheral places are visited for the sake of the facilities they house.

The wakeboarding centre has spatial identifiers that are both unique and particular as well as amorphous and versatile. Being in the middle of two contexts does not make the building boringly mediocre, but instead, namely prevents it from dissipating into the ordinary. The building enfolds warmth as well as a bit of playful ferocity, non-typical solutions that are kind of forbidden but still found in purely functional industrial stock. The building is not opposed to anything, but stands next to something, appropriately rogue.

HELMI MARIE LANGSEPP is an architect at the architectural consultancy b210.

HEADER photo by Joel Pärle

PUBLISHED: Maja 104 (spring 2021), main topic What’s Happening?