FAHLE PARK GALLERY STREET

Location: Tartu hwy 80, Tallinn

Landscape architecture: Mirko Traks, Juhan Teppart, Uku Mark Pärtel, Kristjan Talistu, Karin Bachmann / Kino Landscape Architects

Collaborators: Sten Mander, Alari Suurmets

Architecture: Margit Aule, Toomas Adrikorn, Katri Mets, Laura Ojala / Lumia; Margit Argus, Katariina Teigar / studio Argus

Engineer: Innopolis Insenerid

Commissioned and built by: Fausto Capital

Project: 2018–2019

Completed: 2020

Awards: The Annual Award of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia in Architecture of New from Old 2021 / The Annual Award of the Estonian Association of Landscape Architects in the Category of Landscape and Building 2021

What is surprising and innovative about Fahle Park Gallery Street compared to earlier reconstructions of industrial architecture?

Creating a new kind of space or reproducing what is tried-and-true?

In Estonia, modernisation of industrial buildings aims for a certain increasingly popular sense of milieu. This can be felt in districts that have already been embraced by the society, such as Noblessner, Telliskivi and Aparaaditehas, but more are on the way (Volta, Põhjala, Krulli).1 There is plenty of industrial architecture in Estonia to modernise, so the trend won’t be coming to an end anytime soon.2 The feeling of pride that comes from revitalising industrial heritage has become quite common in Estonia. Faith in these kinds of projects was already demonstrated with the events held in Kultuurikatel in 2017, on the occasion of Estonia’s presidency of the Council of the European Union.3 How on earth could you host top European officials in former industrial premises? And yet, there is something about it that works. Maroš Krivý has described Kultuurikatel and other ruin-like restored industrial spaces as monuments to the Digital Age that left the Industrial Age in ruins and whose own digital infrastructure is difficult to represent physically. Krivý views industrial ruins as a symbolic backdrop to the ‘social factory’, a form of capitalism described by Italian philosopher Paolo Virno where the production of value has been neoliberally dispersed over the whole society. In Estonia, this is embodied in the unwavering faith in the wonders of start-up economy.4

Reworkings of industrial architecture can be characterised on a spectrum of intensity of intervention. On the one end, there is grand modernisation in which the former milieu can be hardly recognised (e.g., Rotermann), whereas on the other, there is seemingly light tidying up and re-arranging the space for holding events (e.g., Kultuurikatel).5 The only real variable is namely the intensity with which the old spaces are intervened in. The tools are largely the same. A much more difficult issue is, how to avoid reproducing previous solutions and bring something new into play?

The spatial approach in modernising old factory districts has been regrettably homogenous in our small country—architects have developed a uniform pattern. The shell is already there, so it is the space between the structural parts—both inside and outside—towards which all the creative energy is directed. All the non-load-bearing parts are usually torn down to make room for large, spacious rental spaces. But this uniformity does not diminish the interest of real estate developers or users—demand determines the supply.

The face of Fahle Park

Fahle Park, a commercial district taking shape in the city centre, with a total of 31 800 m2 of rental spaces, seems at first to go for a more intensive kind of intervention. Fahle House (KOKO, 2007) in particular strikes out in this regard; subsequent volumes seem to blend with history somewhat more. The location of Fahle Park is unique—only a kilometre away from the centre point of Tallinn’s downtown, but also at the intersection of the main traffic arteries in the capital. The district lies on the plot of a former paper mill, which used to be managed by Emil Fahle in the beginning of the last century. The core of the district is formed by a set of buildings with limestone facades, designed by Estonia’s greatest master of Art Nouveau architecture Jacques Rosenbaum, built in 1909-1913, and now under heritage protection.6 Hence, the limestone facades were to be preserved. Lumia architects took this rather as a call to look for value in heritage than a limitation. ‘These buildings and their details form a gentle and unique space, whose preservation requires the delicate eye and hand of an architect,’ say architects Margit Aule and Toomas Adrikorn.7

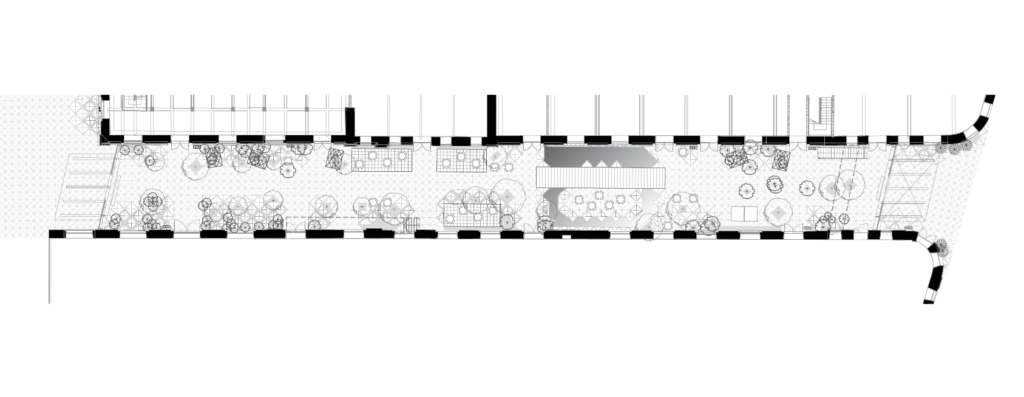

Fahle has quickly become an alluringly modern commercial district while retaining its historical feel. Although the district is still under construction, the first milestones have been fruitful. Its main attraction is the Gallery Street, which has by now become the face of Fahle Park. According to the architects, the most important aspect in designing the Fahle Gallery Street was the restoration of the historical Tselluloosi street—once walkable, but gradually closed from its end as well as above since the 1920s. From the diverse history of the complex, it was decided to restore Rosenbaum’s Art Nouveau architecture, which was hidden beneath several layers. However, designing a glass roof turned out to be a great challenge. After tearing down the bits that had little to no value, the walls were left full of holes, but filling these gaps presented a special opportunity to support the structures bearing the glass roof. The cornice was in a relatively poor state, so it was replaced with a new one made of reinforced concrete, which could also be used to support the roof-bearing structures of the gallery.8

Fahle Park has been fitted with an insulated tropical gallery street—a first not only for Estonia, but all the Nordic countries. It can be said that with this Gallery Street to enliven public space, Fahle has succeeded in distinguishing itself from other modernisation projects.

Gallery Street as an integral part of a whole

In addition to providing lots of office spaces, commercial districts also need to take into account the overall image of the neighbourhood. Usually, these districts are private projects where the creative work of the architect is not dependant on public funds. Thus, creating public spaces within commercial districts is quite testing, but also of key importance. Fahle Park has been fitted with an insulated tropical gallery street—a first not only for Estonia, but all the Nordic countries.9 It can be said that with this Gallery Street to enliven public space, Fahle has succeeded in distinguishing itself from other modernisation projects.

The Gallery Street raises the bar for the quality of public space quite high indeed. The feeling that one gets when turning from Tartu hwy to the Fahle street already provides a strong enough argument—upon entering the doors, one is whisked away to serene tropics where no traffic noises can be heard. Instead, there are sounds reminiscent of a rainforest and burbling from special rainwater gutters, creating a cosy atmosphere. This in turn enhances the effect that one gets on entering the gallery from the city streets. It is precisely the Gallery Street that turns the Fahle district really into a park. The novel solution has retained the necessary historical feel while still adding new qualities unforeseen in the Nordics to the set. The Gallery Street also tends to attract photographers, especially for taking bride-and-groom pictures. Fahle shows how reinterpreting industrial architecture need not be restricted to interiors, but can also contribute to improving outdoor spaces.

Pushing the boundaries of landscape architecture

The Fahle Gallery Street strikes as a symbiosis of a rest area and meeting place. It lies between two building volumes and serves as a connection within the district as well as a passage for pedestrians. Commenting on the Gallery Street, interior architect Margit Argus has said that the most successful projects are those where the visitor is unable to make out the boundaries between interior architecture, architecture and landscape architecture.10 This sort of fluency can indeed be felt there. The street has a calm vibe that is kind of therapeutic. You can enjoy your coffee on terraces as well as in more private corners. It is a bit unfortunate, though, that the only eating place opening directly to the Gallery Street is a restaurant rather than a cafe—the latter would be a more suitable function there. The two cafes by the gallery merely glimpse at the street through a couple of windows.

Several kinds of exotic plants usually not seen in Estonia are growing on the street. The most suitable flora was chosen by KINO landscape architects together with gardener Alari Suurmets. Thanks to district heating devices, it is possible to maintain the temperature of 16–20°C all year round. This enables to grow orange, tangerine and lemon trees, bamboo, fig trees—most of which were, granted, imported from abroad. In addition to the flora, there is also a pool of Japanese koi.11 Landscape architect Karin Bachmann explains that similarly to the outdoor areas in the Fahle district, the gallery is meant to enact a space that looks as if it has been out of human use for decades. Every nook and cranny serves a practical purpose—cracks and crevices have become fixing points for climbing plants; the humus that has gathered under open pieces of rock provides solid protection for delicate roots; scratches have come to accommodate fungi. The lushness of the tropical biotic community at the same time brings to mind all the Estonian vegetation that is freely burgeoning in barrens, forests and swamps—the safe, warm and green gallery is a convenient scale model of this unrestrained wilderness.12

The Gallery Street raises the bar for the quality of public space quite high indeed. The feeling that one gets when turning from Tartu hwy to the Fahle street already provides a strong enough argument—upon entering the doors, one is whisked away to serene tropics where no traffic noises can be heard.

A commercial district of the future

An increasingly important aspect of new property developments is environmental sustainability. Businesses are becoming more aware each year and try to impress their clients with their green choices. Commercial districts need to take this into account in order to prove themselves to their businesses. Granted, reconstructing pre-existing architecture in the city centre is in itself a green undertaking. In the light of increasingly stringent norms, Fahle has also incorporated certain novel technologies into its conception, including the first district cooling system in Tallinn.13 Yet the question of ecological sustainability still remains, given that they have an e n t i r e s t r e e t that is constantly kept at a room temperature level. Although the developers of Fahle Park emphasise their aim to be pioneers in environmentally-friendly commercial real estate development (claiming to keep their CO2 footprint as low as possible),14 maintaining such a gallery street seems controversial in this respect. In terms of public space improvement, the street is surely justified, but its greenness is limited to its flora.

Nevertheless, Fahle Park has had great success with finding tenants, which also led to the emergence of a strong IT-community, similarly to Ülemiste City. Almost all of the 30 000 m2 completed so far found tenants in the first year, including companies such as Postimees Group, Apollo Group, Stora Enso, and the career centre of the Estonian Unemployment Insurance Fund.15 Fahle Park was named the project of the year in 2020 by the Estonian Association of Real Estate Companies, and the Gallery Street received the annual ‘Old to New’ award from the Cultural Endowment of Estonia and ‘Landscape and Building’ award from the Estonian Landscape Architects’ Union at the Estonian Architecture Awards.16 All in all, Fahle Park Gallery Street is a powerful example of the possibilities of landscape architecture and worthy of its accolades. Revitalisation of industrial heritage has given us a room-temperature indoor street with subtropical flora. Being the first project of its kind in the Nordic countries, Fahle Park Gallery Street takes the quality of commercial real estate surroundings several notches up, and achieves this mainly by improving public space.

HELIN KULDKEPP is a 4th-year architecture and urban planning student in the Estonian Academy of Arts.

HEADER photo by Juhan Teppart

PUBLISHED: Maja 109-110 (summer-autumn 2022) with main topic Built Heritage and Modern Times

1 Urmo Mets, ‘North-Tallinn fits a Tartu-full of People’, Maja, Spring 2022 (108), 96–101

2 Barbara Brigita Oja, ‘Suur ülevaade: valminud ja valmimas arendused Tallinnas ja Tartus’, Postimees, 10.06.2019, https://majandus.postimees.ee/6704013/suur-ulevaade-valminud-ja-valmimas-arendused-tallinnas-ja-tartus.

3 Anette Parksepp, ‘Eesistujad meenutavad: kajaka päästmine ja Macroni kohtumine kööginurgas’, ERR, 09.11.2017, https://www.err.ee/641466/eesistujad-meenutavad-kajaka-paastmine-ja-macroni-kohtumine-kooginurgas.

4 Maroš Krivý, Andres Sevtsuk, ‘Theoretically Grounded Architecture: Where Did it Disappear?’, interviewed by Kaja Pae, Maja, Spring 2020 (100), 16–18.

5 Henry Kuningas, ‘The Industrial Heritage of Tallinn Set for A New Lease of Life,’ Maja, Spring 2022 (108), 32–45.

6 Jaak Juske, ‘Fahle ajalugu’, Fahle Park, https://fahle.ee/et/keskkond/kontseptsioon.

7 Margit Aule, Toomas Adrikorn, e-mail interview with the author, 12.06.2022.

8 Margit Aule, Toomas Adrikorn, e-mail interview with the author, 12.06.2022.

9 Kristina Kostap, ‘Fahle Pargi galeriitänavast on saanud uus kuum koht pulmapiltide tegemiseks’, Postimees, 14.07.2021, https://kodu.postimees.ee/7292821/fotod-fahle-pargi-galeriitanavast-on-saanud-uus-kuum-koht-pulmapiltide-tegemiseks.

10 Margit Argus, ‘Trendid muutuvad, mööbel laguneb, aga ruum jääb,’ interview by Grete Tiigiste, ERR, 06.06.2022, https://kultuur.err.ee/1608620674/sisearhitekt-margit-argus-trendid-muutuvad-moobel-laguneb-aga-ruum-jaab.

11 ‘Fahle pargis valmib eksootiliste puudega sisetänav’, Ringvaade, 09.11.2020, https://menu.err.ee/1157065/ringvaate-video-fahle-pargis-valmib-eksootiliste-puudega-sisetanav.

12 Estonian Architecture Awards 2021 (Tallinn: Arhitektuurikirjastus, 2022), 82.

13 Fahle kvartal saab Tallinna esimese kliimasõbraliku jahutusteenuse’, Kinnisvarauudised, 09.11.2019, https://www.kinnisvarauudised.ee/uudised/2019/07/09/fahle-kvartal-saab-tallinna-esimese-kliimasobraliku-jahutusteenuse.

14 Kenneth Karpov, ‘Fausto Capital seab arendustes esikohale roheteemad ja säästliku mõtteviisi’, interviewed by Helen Roots, Kinnisvarauudised, November 2021, 4–5.

15 Einar Niin, ‘Ärikinnisvara turg on täna stabiilne,’ Ettevõtlusteataja, 04.11.2020, https://podcasts.google.com/feed/aHR0cHM6Ly9mZWVkcy5idXp6c3Byb3V0LmNvbS8xMDUwMTU3LnJzcw/episode/QnV6enNwcm91dC02MjE3MDgx.

16 Estonian Architecture Awards 2021 (Tallinn: Arhitektuurikirjastus, 2022), 82.