KÄRDLA SCHOOL

Architecture: Ott Alver, Alvin Järving, Mari Rass, Lisett Eist, Kaire Koidu, Jõnn Sooniste, Andreas Krigoltoi / Arhitekt Must

Interior architecture: Kadri Karmann, Mari Põld, Maria Liiva / T43 Sisearhitektid

Landscape architecture: Mirko Traks, Karin Bachmann, Juhan Teppart, Uku Mark Pärtel, Kristjan Talistu / KINO Maastikuarhitektid

Project management: Liina Mürk / Infragate Eesti

Structural design: Ivar Muuk / Inseneribüroo PIKE

Project, building: 2019-2021, 2023

Client: Hiiu vallavalitsus

Total area: 2500m2

In Kärdla School in Hiiumaa, designed by Arhitekt Must, outdoor recess is not some laborious ideological effort, but simply an ordinary and natural idea, writes Kadri Klementi.

Autumn is a special time in Hiiumaa. The weather is still fair and nature still vibrant. Sunrays, rain showers, clouds gliding across the sky, the smell of wet soil, apples in green uncut grass, wind ruffling the treetops high above your head. And the silence! After all the summertime hustle and bustle, it lies there like a seal on a beach boulder: large, plump and indulgingly overflowing. The silence is torn in two only by the island children’s mopeds, which convert thirst for adventure and fossil fuels into deafening engine noise with exemplary efficiency. In their own way, they too are a measure of that sprawling silence—their comings and goings can be heard from a long distance. If you approach the school at ten o’clock in the morning on a school day, however, the third class is already in session and the street that leads from the main square toward the schoolhouse is moped-lessly calm.

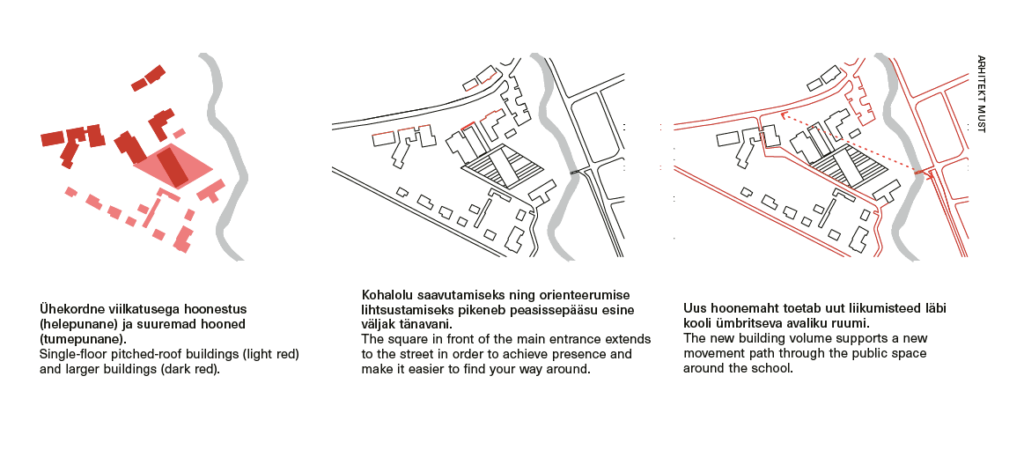

The way from the very centre of Kärdla to the school is not long, but the building itself remains hidden as you get nearer. You do see the secondary school building, the ‘backside’ of the gym and the lovely historical building of the music school, but those looking for the elementary school are reaffirmed only by a yellow steel wireframe rising between these other volumes, on which there are large letters announcing that this is indeed where Kärdla School is located. The emptiness winks at you and reminds you that Harry Potter likewise refused to believe at first that his school exists. Here, too, are those in the know able to step (imaginatively) into a parallel world and see a charming oasis with a spacious canopy, which was originally included in the winning entry of the architecture competition, and which would intuitively line up the school with the neighbouring street-side buildings.

The canopy in front of the school together with the landscape solution for it proposed in the competition entry fell victim to the budget blowing up due to global developments. The schoolhouse that has been left bare now stands ashamedly behind others, with its low roof hanging like a large hat pulled over eyes. Numerous large windows reflect the surroundings on a grey morning and do not let the guest cast a glimpse inside. The moodily silent building is supported by its similarly mute adjacent companions: the music school’s small, windowless shed on one side, an immense and impressively featureless gym wall on the other. The brown-coloured wood siding of the new school is itself reminiscent of sheds, but here we should keep in mind that in a garden town, sheds are an utterly essential and even captivating phenomenon, since they are capable of fulfilling a gazillion practical needs and at the same time of functioning as treasuries of childhood fairy-tale discoveries, experiences and fantasies. Sheds hide what is inside, and you can never be quite sure whether you are allowed to peek in the door—indeed, sometimes you are not (although this does not mean that you won’t do it).

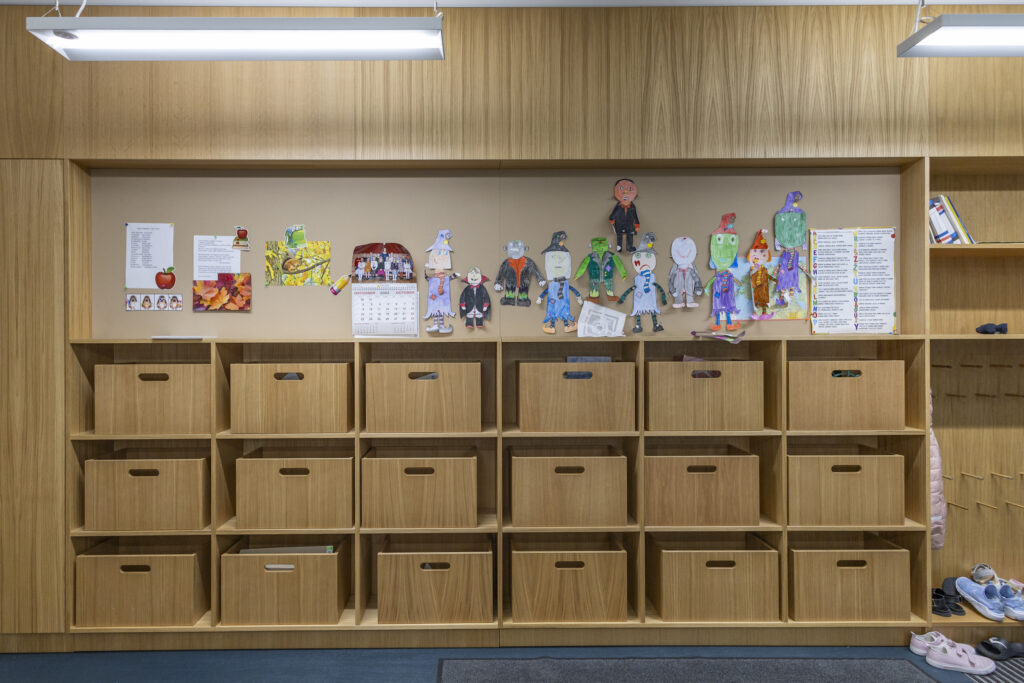

Therefore, entering the schoolhouse is undoubtedly a harrypotterish experience—the building that had just a moment before appeared reticent and restrained turns all of a sudden into an open, warm and living space. The wooden interior, occasionally in pleasantly thick colours, is so well-proportioned as if someone had measured it out for the comer. Although classes are in session and no students are to be seen, it is evident that we are in the heart of the school’s everyday life. The chairs, benches and boxes in the cafe-like dining hall have been left to flock affably around tables, the pillows and tabletops on the central flight of steps are each facing in their own direction, the curtain that separates a multi-purpose area so that a physical education class could be held there hangs in large nonchalant folds and thus softens what you perceive with your eyes and ears, and the airy dressing room area is lined with rows of sneakers that lie there like boulders around a small islet. There are also shelves for the footwear, by the way, and some shoes have even made their way there, but a large number seems to roam freely instead. You probably would not call this sort of arrangement expedient or pretty, but it sure is a homely, lively and a sincerely authentic sight.

Similar sneakers that have seemingly been left behind on the fly can be found elsewhere in the building. With its numerous exits, the building actually succeeds in tying together indoor and outdoor spaces in a close and substantive—rather than merely visual—manner. There is outdoor access from nearly every first-floor room. All classrooms for elementary grades have their own wardrobes, which is why outdoor recess here is not some laborious ideological effort, but simply an ordinary and natural idea—as it should be. There are also spacious sheltered courtyards for rougher weather, and wild nature with its simple abundance of tall alder and maple trees, goutweed, anemones and small Nuutri river is just a step away. A truly Bullerby-like environment, in which each participant acquires the habit of active physical movement unobtrusively and naturally—a habit that is also prescribed by all sorts of curricula, development plans, health promotion programmes and what not, and that needs to be pursued in other buildings all too often with tiresome artificial methods and tricks. We can imagine that here the environment itself will take care of it much more efficiently.

A shorter way to the outdoors is of key importance at a time when lack of physical mobility is an increasingly serious and expensive social problem. The wardrobes that bring the outdoors so close in this schoolhouse are compact, to put it euphemistically. One can get cold sweat by imagining the seventy-two hands and feet, bursting with energy and rushing into sleeves and trouser legs all at once when recess arrives. And yet, it is nevertheless great that there are such wardrobes at all, in spite of the fact, known for many years already, that the number of square meters foreseen by the ministry does not allow creating contemporary school spaces, which are necessitated by the contemporary curricula developed in another ministry.

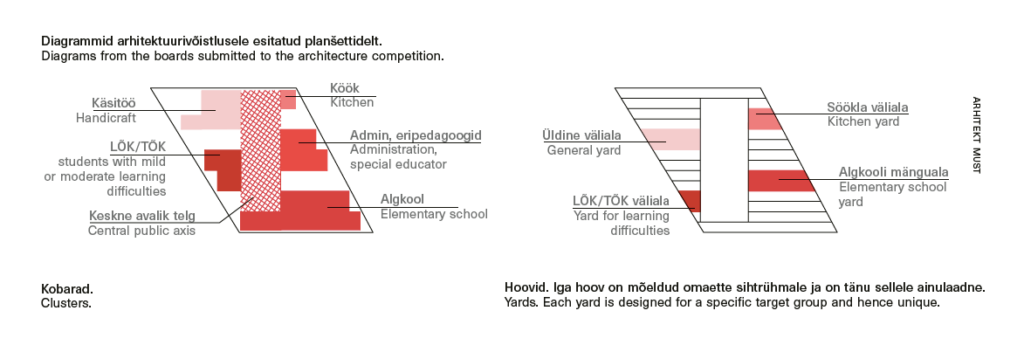

Masterfully achieved compactness also characterises the school building as a whole. From the outside or on paper, the building does not seem that small, for the canopies between the volumes generate the impression of a building that spreads out like a carpet. Inside the building, however, it is clear that the school consists of clusters of classrooms connected by a rather scant in-between space that has been cleverly designed to serve multiple purposes. There are almost no empty corridors that are there only for passing through. Everywhere, it is possible to study, teach, relax, get refreshed. The interior design also creates opportunities for physical mobility—climbing, dancing, hanging, balancing, hopping, swinging and even somersaulting, when one feels like it.

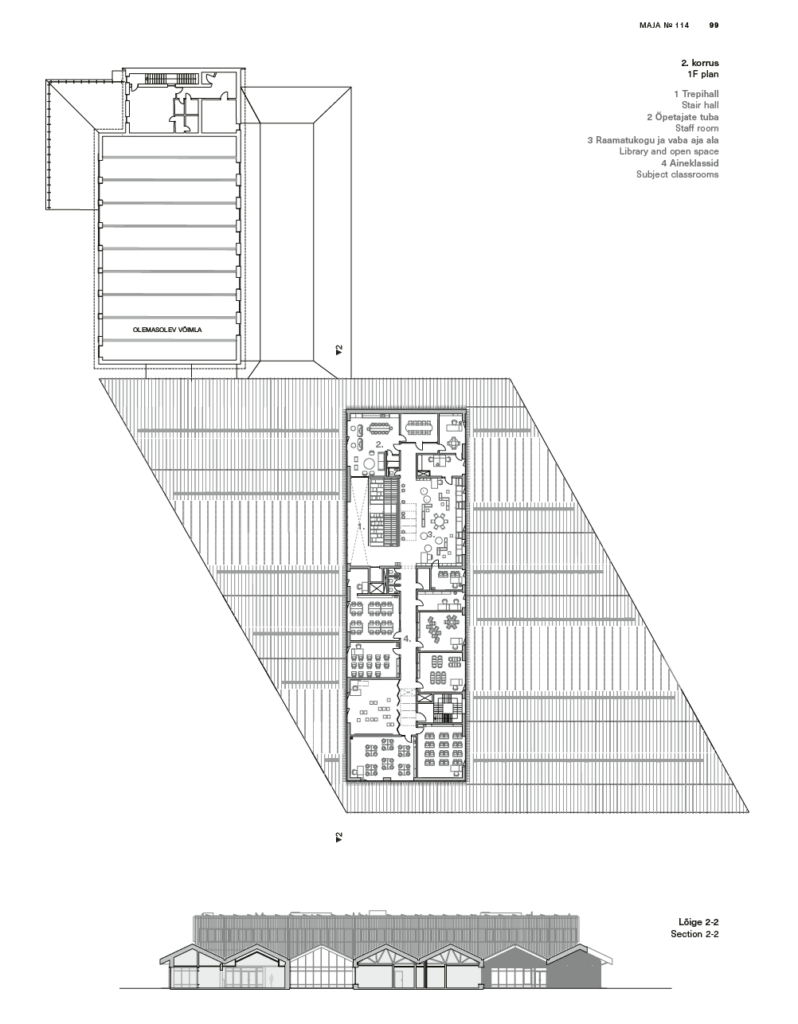

The lobby and the adjacent dining hall with a curtain-separable group work area, open kitchen, flight of steps with moveable tables, curtain-separable notional assembly hall and its extension, stepped music classroom and stage with a soundproof dividing wall that can be used as a whiteboard, not to mention a couple of nearest covered courtyards, which can be merged with the indoor space by opening large two-sided doors, all combine to form a space that ignites the imagination and enables cross use. All kinds of use scenarios unfold in one’s mind’s eye, from graduation ceremonies to conferences, hackathons to theatre plays, student invention fairs to hobby acrobatics performances, stock market simulations to astronauts giving guest lectures. All of it is within the realms of possibility, and some of it has already been tried out in the first three weeks of activity.

From the very same lobby, one can access the second floor, where there are subject-based classrooms, teacher’s staff room with a couple of offices, library and a small open space mainly for older school students. The teacher’s staff room struck me as spacious, although this was probably first and foremost due to it being empty at the moment, or due to the contrast with the narrow, windowless meeting room that I experienced immediately before. The most intriguing and polemical solution in the whole building is the large interior window of the staff room, from which there is a wide view of the steps at the heart of the school, its main traffic junction. There is even nothing figurative about it—every student indeed has to scuttle past this guard tower, for there is no other way. The classic prison analogy is further strengthened by large metal strips behind the windows that envelop the whole perimeter of the second floor. This is childish joking on my part, of course—though it is great that a basic school building can stimulate one’s inner preadolescent in such ways—because the interior windows and the views from and into them render the school space more roomy, more airy and more exciting.

The library and its open space are yet to be furnished. Hopefully, the new school building encourages and inspires the youth to participate in the furnishing process. Space is a major influence on the youth’s habits and mentality—it often happens that students (and teachers) coming to a new school building have already been moulded by the factory-like classrooms of the previous era and so they continue their daily lives like before, sometimes not even noticing and using the possibilities that the new space offers. During our brief encounter, however, the students were already proposing LED light chains for the library and requesting a practical shelter for bicycles. This is a good start, and it could be these lights are indeed in place by now. And yet, how to furnish and exploit the roofed courtyards all year round? How to become a physically mobile, self-governing, creatively thinking student or teacher—or human being—when the environment is conducive to it, but the ‘architecture’ of habits originates from the old building?

Kärdla School is a textbook example of the importance of collaboration and dedication of different parties in creating good public space. A significant part of childhood and youth is spent in school (as is even required by law), so it needs to be a very well-designed place indeed, and its designers bear a great responsibility. The design and construction of every public space is carried out under budgetary and timetable pressures, and it is not uncommon for these pressures to be very heavy. In such a situation, architects—the authors of the building as well as municipal architect qua client’s representative—need to show much prowess both in designing and negotiating, thorough knowledge of teaching and learning, flexibility and cooperative skills, as well as certain unshakable convictions. Architects need to be able to represent those still without a voice in decision-making. At the meeting table, they too are initially invisible like their schoolhouse, kicking their heels (because mobility is natural to them), ready to fluently list the values of being human and tell enthusiastically about the fox traps that they have built by the river next to the schoolhouse—because they are happy, enterprising, creative and independent thinkers, doers, and they have a schoolhouse to support it.

KADRI KLEMENTI works in architectural office b210, runs the School of Architecture and is an architecture teacher.

HEADER photo: Joosep Kivimäe

PUBLISHED: Maja 114 (autumn 2023) with main topic ISLANDS