Time

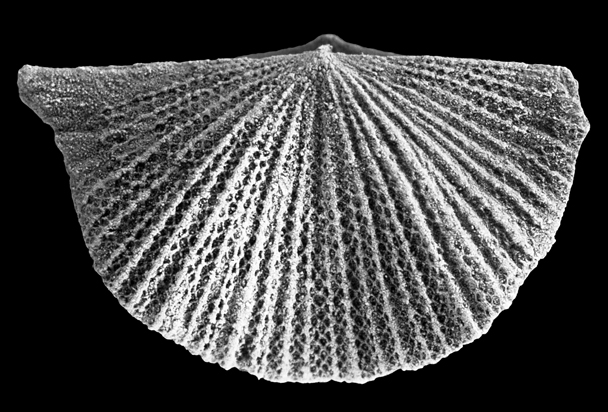

I am staring at a wall. My brain (just like yours) consists of about 80% water. Water has been circulating on Earth for at least four billion years. Approximately 470 million years ago, the very same water that now nourishes and nurtures my brain cells became the habitat of echinoderms, lime-shelled brachiopods and trilobite arthropods. Clastic bits of these and other ancient creatures are the main component of the limestone found along the northern coast of Estonia.1 About 50 million years later, the very same water in shallow tropical lagoons was home to sea scorpions and agnathans, whose fossils can be found in the clayey dolomite of Saaremaa.2 Including in Tagavere dolomite, thin slabs of which are currently crumbling off the walls of Linnahall.

What a strange (bit of hi)story—for millions of years, certain creatures have lived and then died and then transformed chemically and physically into hundreds of different materials that I take for granted. And of course I take them (for granted)—in the world I live in, these materials have always been present. As a human being, I am a cocktail of organic matter that, since the dawn of time—the Stone Age—has been grabbing materials of the past to mould them into present and future. We are infinitely dependent on the past.

Character count

Linnahall was completed in 1980, which means that it is 44 years old. In my lifetime, it has always existed (as a given). 45% of current Estonian residents, however, have also lived in a world where Linnahall was still the future.3 Sometimes I wonder if we perceive the buildings that we have seen being erected as somehow more temporary.

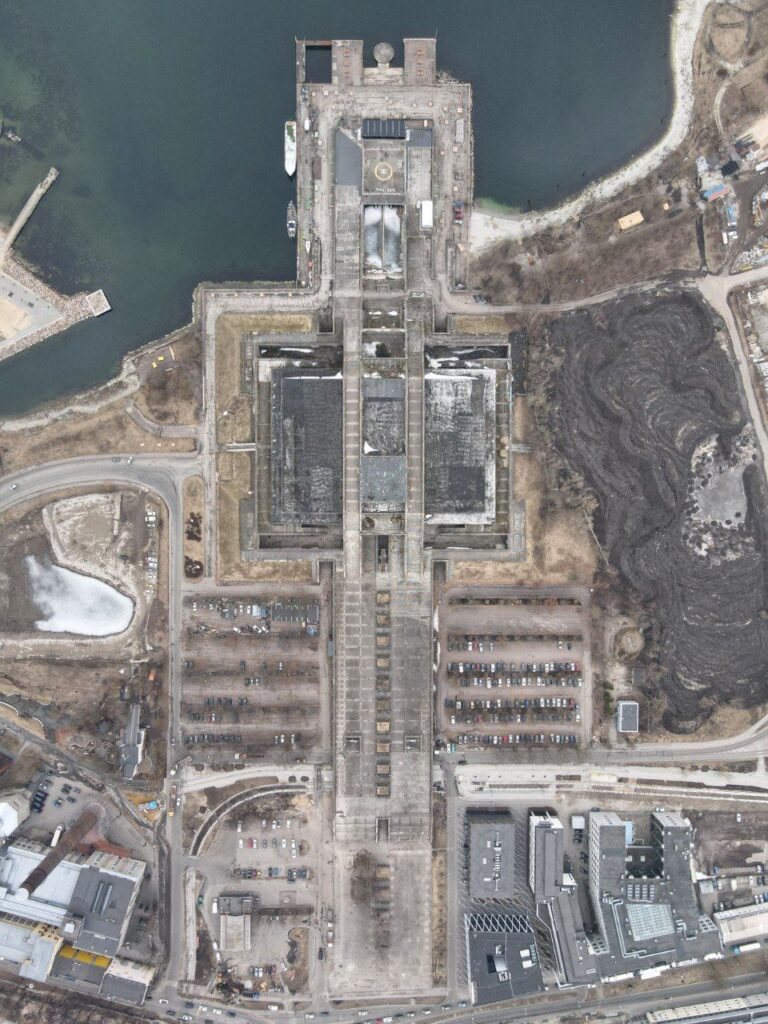

Given the relatively young age of Linnahall, it has an impressive character count to its name: tens (if not hundreds) courseworks and master’s theses, art projects, delieveries at biennales, idea competitions, cost–benefit analyses, expert opinions, cacophonous comment sections—no other ouevre in Estonian architecture manages to stir up so many passions and debates. Of course there are many other relatively recent ideological ghosts scattered throughout the region: from manor houses, to kolkhoz centers, factories and memorials, but both the prominence in urban setting as well as multifaceted liminality make Linnahall an unequaled stage for the attitudes and frictions of the society.

In fact, perhaps Linnahall is not a stage at all, at least not in the sense of being a passive setting, but rather itself an active actor in the play—a character who keeps inviting (or calling) you out. Drags you to the roof at sunset. Or invites you in. To a concert, to an estrada show, into a discussion round. To karaoke and bowling. Challenges to a duel. To ponder over the principles of a good urban space. To dissect heritage protection issues. To make sense of intellectual property rights. Linnahall unites and divides. It is reminiscent of ….something? Of what? Of something familiar and something alien. That there is not enough money and that more is needed. It rambles on about factories and dismantlings and architectural qualities and curiosities of the construction industry. Among other things, it rambles about the dolomite slabs stuck on with an inappropriate cement mix allegedly made it to the walls of Linnahall partly due to the stone being expensive, and unlike strictly regulated industrial materials such as concrete, silicate stone or steel, sedimented sea scorpions and agnathans enabled the construction trust to set the price of the work (and hence the profit) themselves.

Karst landscape and bastion

Riina Altmäe, one of the architects of Linnahall, has described the interior of the building figuratively as a karst landscape—a space made up of stalactites and stalagmites that humans have slightly altered, reinforced and adapted according to their needs and possibilities.5 For a karst landscape to form, there needs to be rock that can be dissolved by moving groundwater, but one that is still resilient enough so that cracks and other karst forms would not immediately make it collapse.6

Linnahall has often been compared to the (now obsolote, yet currently restored) bastion walls surrounding the Old Town of Tallinn. The word ‘project’ emerged in the modern sense in parallel with increased use of firearms in warfare, which made fortification design the paramount field of the building sector. Compared to previous architectural works, these new edifices required unprecedented speed and precision in terms of planning. Rigorous drawing techniques began to be used—such as orthogonal projections that helped careful advanced planning of necessary labour and resources and gave assurance about where the endeavour was headed.7

Thus, bastions and Linnahall are also similar in that they are both consciously designed. The design methods of Linnahall as well as modern planning methods in general have, through many twists and turns, grown out of bastions. Karsts are not consciously planned; neither the settling time nor the creatures in it know where we are headed. Karsts are not eternal. Yet, in the present moment, they are impressive landscape wonders—and this is something common to all: karsts, bastions as well as Linnahall.

In Estonian words ‘imelik’ (strange) and ‘imeline’ (wonderful) reveal that strange can be equally wonderful. It is both strange and wonderful that we never quite know what leads to what. That we, too, are part of the sedimentary and transformative flow of time (sedimentary rocks generally form in bodies of water, caves or deserts, so we with our anthropogenic sediments such as Linnahall are probably not turning into limestone just quite yet). In any case, the brief for or the aims of an architecture project rarely call for it to be an ignition for discussions, to be something that would offer possibilities for intense etudes even in the politest lunch tables. And yet, it is possible to gradually settle into something that does just that.

MADLI KALJUSTE is a freelance architect who is exploring life through houses.

HEADER photo by Martin Siplane

PUBLISHED: MAJA 1-2024 (115) with main topic STONE

1 Heldur Nestor, Alvar Soesoo, Ari Linna, Olle Hints, Jaak Nõlvak, Ordoviitsium Eestis ja Lõuna-Soomes (Tallinn: Geoguide Baltoscandia, 2006).

2 Heldur Nestor, Alvar Soesoo, Silur Eestis (Tallinn: Geoguide Baltoscandia, 2006).

3 Statistics Estonia, Population pyramid of Estonia, https://www.stat.ee/rahvastikupyramiid/?lang=en

4 Veronika Valk, Ivar Lubjak, Maria Pukk. „Unista > taju > kohane > toida ehk mida teha Tallinna linnahalliga“, Akadeemia 11 (2012).

5 Ene Pajula, „Meeldivad vanad konstruktsioonid“, Õpetajate leht, 05.11.2010.

6 Ülo Heinsalu, Karst ja looduskeskkond Eesti NSV-s (Tallinn: Valgus, 1977).

7 Pier Vittorio Aureli, Architecture and Abstraction (MIT Press, 2023).