The ELME project of the Environment Agency deals with mapping of ecosystem services and develops innovative methods for collecting and displaying information about biodiversity.

Disputes about the benefits of nature, i.e. the value of ecosystem services, and especially their pricing and possible marketing, have recently been gathering momentum. Two of the issues considered are the readiness of people to actually pay for using the benefits of nature and the adequacy of the environmental charges established to protect these benefits. Before we try to answer these questions, we need a comprehensive nationwide overview of ecosystem services, which we do not have yet.

This is one of the reasons why the ELME project was launched.1 An action plan for mapping, assessment and prognosis of ecosystem services has been ordered. The coming stages of the project will include identifying the geographic variety of ecosystem services, their basic and critical levels, as well as potential and deficiencies of the capability for provisioning benefits, determining the prerequisites ensuring that the carrying capacity of ecosystem services is not exceeded, and so on.

Completion of the green network planning guidelines

The analysis of the functionality of the green network so far included in county-wide spatial plans and comprehensive plans and green network planning guidelines for comprehensive plans will be completed within the scope of the project this spring. One of the most important goals of the green network is to ensure the ecological coherence of habitats, i.e. the adequacy of the habitats and the corridors for the distribution of species and migration between them. Larger and more valuable natural areas are mostly under protection, so the focus should be on the corridors that connect these areas, but have largely been left without any administrative protection. This means that corridors should be wide enough, there should be no extensive interruptions (artificial surfaces, clear cutting, etc.), or structures like wildlife crossings and fish ladders are planned to mitigate the impact of the interruptions. The confluences of land use must also be considered – for example, clear cutting by the mouth of a wildlife crossing must be prevented.

The establishment of the purposeful network will succeed if the specifics and incompleteness of the underlying spatial data are considered, e.g. under- or overestimation of biodiversity in certain regions due to the peculiarities of the different biodiversity databases (e.g. bogs seem to be very rich in species, but they have actually been more thoroughly studied in comparison with other areas). More attention should be given to the ecosystems that have so far been underrepresented in the green network (meadows, wetlands). It must also be noted that the terms of use established in the green network for the protection of the benefits of nature can be implemented in practice only if they are clearly worded, understandable in terms of the technical solution (the location is shown on the map or map layer) and well accessible (in digital format).

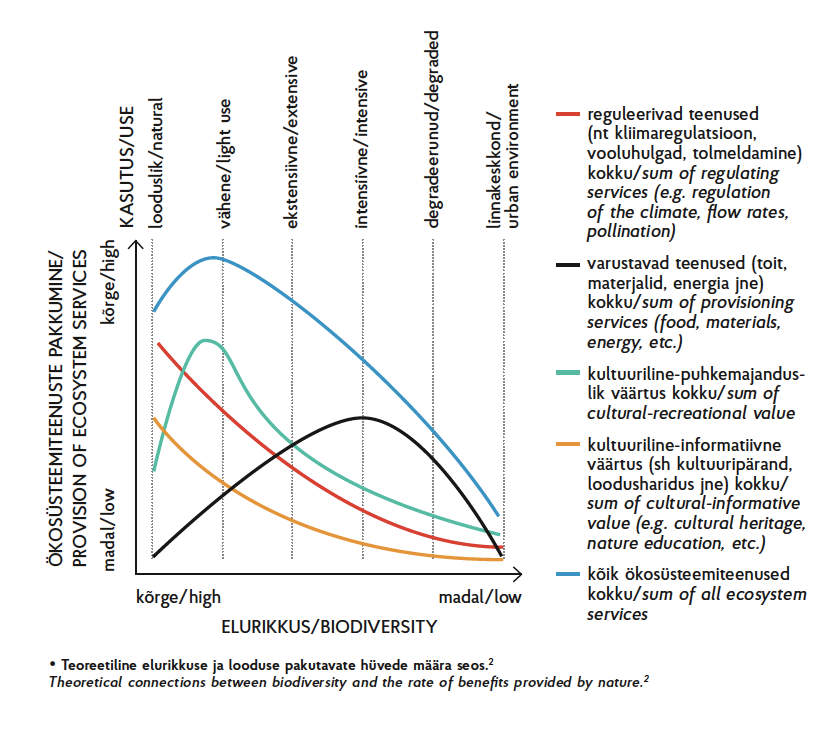

Guaranteeing ecosystem services for various stakeholders must be considered when the green network is being planned and in the case of the other spatial decisions that concern the environment. However, it is necessary to make sure that the material benefits with actual market value, i.e. provisioning services (e.g. provision of timber), are not the only ones preferred. Theoretically, an increase in the supply of provisioning services is related to a decrease in biodiversity as well as cultural and regulating services (see the figure). For example, intensive agriculture provides a lot of food, but it also has a significant negative impact on biodiversity.

MADLI LINDER is a Leading Specialist at the Nature Department of the Environment Agency and the manager of the ELME project.

PUBLISHED in Maja’s 2018 spring edition (No 93).

HEADER photo by Anna-Liisa Unt. Estonian National Museum in Tartu.

1 The project “Establishment of tools for integrating socioeconomic and climate change data into assessing and forecasting biodiversity status, and ensuring data availability” (ELME) is funded by the European Union Cohesion Fund and the foundation Environmental Investments Centre and lasts from 2015 to 2023. The project will be carried out by the Estonian Environment Agency.

2 Adapted from the following sources: Braat, L. & ten Brink, P. (2008). The cost of policy inaction: the case of not meeting the 2010 biodiversity target. Wageningen, Alterra, Alterra-rapport 1718 and Issue No. 11 of the European Commission, May 2015: Science for Environment Policy. In-depth report. Ecosystem Services and Biodiversity.